Difference between revisions of "Margaret Thatcher"

m |

|||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

|death_date=8 April 2013 | |death_date=8 April 2013 | ||

|image=Margaret Thatcher.jpg | |image=Margaret Thatcher.jpg | ||

| + | |name=Baroness Thatcher | ||

|image_width=200px | |image_width=200px | ||

|title=Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |title=Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | ||

|wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Thatcher | |wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Thatcher | ||

|spartacus=http://spartacus-educational.com/COLDthatcher.htm | |spartacus=http://spartacus-educational.com/COLDthatcher.htm | ||

| + | |historycommons=http://www.historycommons.org/entity.jsp?entity=margaret_thatcher | ||

|spouses=Denis Thatcher | |spouses=Denis Thatcher | ||

| − | |alma_mater=Somerville College | + | |nationality=UK |

| − | |constitutes= | + | |description=Three term UK PM whom the UK Deep State used to push through radical [[privatisation]]: "There is no such thing as society." |

| + | |alma_mater=Somerville College (Oxford University), Inns of Court | ||

| + | |constitutes=lawyer, politician, deep state functionary | ||

|birth_name=Margaret Hilda Roberts | |birth_name=Margaret Hilda Roberts | ||

|birth_place=Grantham, Lincolnshire, England, UK | |birth_place=Grantham, Lincolnshire, England, UK | ||

| Line 16: | Line 20: | ||

|political_parties=Conservative | |political_parties=Conservative | ||

|children=Carol Thatcher, Mark Thatcher | |children=Carol Thatcher, Mark Thatcher | ||

| − | |parents=Alfred, Beatrice | + | |parents=Alfred Thatcher, Beatrice Thatcher |

|powerbase=http://www.powerbase.info/index.php/Margaret_Thatcher | |powerbase=http://www.powerbase.info/index.php/Margaret_Thatcher | ||

|sourcewatch=http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Margaret_Thatcher | |sourcewatch=http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Margaret_Thatcher | ||

| + | |wikiquote=http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Margaret_Thatcher | ||

|employment={{job | |employment={{job | ||

| − | |title=UK Prime Minister | + | |title=UK/Prime Minister |

|start=4 May 1979 | |start=4 May 1979 | ||

|end=28 November 1990 | |end=28 November 1990 | ||

|description=Appointed after [[Le Cercle]]'s intervention, possibly through the [[Shield]] committee. | |description=Appointed after [[Le Cercle]]'s intervention, possibly through the [[Shield]] committee. | ||

}}{{job | }}{{job | ||

| − | |title=Leader of the Opposition | + | |title=UK/Leader of the Opposition |

|start=11 February 1975 | |start=11 February 1975 | ||

|end=4 May 1979 | |end=4 May 1979 | ||

}}{{job | }}{{job | ||

| − | |title=Leader of the Conservative Party | + | |title=UK/Leader of the Conservative Party |

|start=11 February 1975 | |start=11 February 1975 | ||

|end=28 November 1990 | |end=28 November 1990 | ||

}}{{job | }}{{job | ||

| − | |title=Shadow Secretary | + | |title=Shadow Environment Secretary |

|start=5 March 1974 | |start=5 March 1974 | ||

|end=11 February 1975 | |end=11 February 1975 | ||

| Line 49: | Line 54: | ||

|end=16 October 1964 | |end=16 October 1964 | ||

}}{{job | }}{{job | ||

| − | |title=Member of Parliament for Finchley | + | |title=UK/Member of Parliament for Finchley |

|start=8 October 1959 | |start=8 October 1959 | ||

|end=9 April 1992 | |end=9 April 1992 | ||

| + | }}{{job | ||

| + | |title=Member of the House of Lords | ||

| + | |start=30 June 1992 | ||

| + | |end=8 April 2013 | ||

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Margaret Hilda Thatcher''' was [[ | + | '''Margaret Hilda Thatcher''' was a UK [[deep state functionary]] who after attending the [[1975 Bilderberg]] experienced a [[Bilderberg boost]] and was appointed [[leader of the UK Conservative Party]]. In 1979 she was made [[UK Prime Minister]] after action by the [[Shield]] committee, a job she retained until 1990. A Soviet journalist called her "The Iron Lady", a nickname which became associated with her uncompromising politics and leadership style. As Prime Minister, she faithfully implemented [[neoliberal]] economic policies of [[privatisation]] for her [[UK deep state]] masters (dubbed "[[Thatcherism]]" by the {{ccm}}).<ref>[https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thegreatnhsheist "The Great NHS Heist Documentary"]</ref> After retiring from the [[House of Commons]], Thatcher was ennobled in 1992 as [[Baroness Thatcher]] of Kesteven in the county of Lincolnshire, which entitled her to sit in the [[House of Lords]].<ref>[http://www.biography.com/people/margaret-thatcher-9504796 "Biography of Margaret Thatcher"]</ref> |

| − | + | == 1970s == | |

| + | [[File:Margaret Thatcher - Jimmy Savile.webp|thumb|350px|left|Margaret Thatcher with [[Jimmy Savile]] at Stoke Mandeville Hospital when she was opposition leader in 1977.<ref>[https://www.newspapers.com/clip/113050973/jimmy-savile-relationship-with-margaret/ The Daily Telegraph, London, Greater London, England, 28 Dec 2012, Fri, Page 5]</ref>]] | ||

| − | + | The 11th February 1975 brought the highpoint of a long campaign which deposed [[Edward Heath]] as [[Leader of the Conservative Party]], replacing him by his former [[UK/Education Secretary|Education Secretary]], the relatively unknown Thatcher. After the intervention of [[Brian Crozier]]'s [[Shield]]<ref>A group set up quite possibly with the express purpose of getting her elected</ref> she prevailed against [[William Whitelaw]] by 146 votes to 79.<ref name=rogue/> Her campaign was run by her private secretary, Tory MP and former [[MI6]] officer [[Airey Neave]], who was assassinated by a [[car bomb]] on 30 March 1979 before he could assume the post of [[Northern Ireland Secretary]]. | |

| − | == | + | === 1975 Bilderberg === |

| − | + | [[Denis Healey]] (then [[Chancellor of the Exchequer]] in the [[Labour Party]] government) recalls that he invited Thatcher to the [[1975 Bilderberg]] conference and that after listening in silence for two days: | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

{{QB| | {{QB| | ||

"the next day she suddenly stood up and launched into a three-minute Thatcher special. I can't remember the topic, but you can imagine. The room was stunned. Here's something for your [[Conspiracy Theorist|conspiracy theorists]]. As a result of that speech, [[David Rockefeller]] and [[Henry Kissinger]] and the other Americans fell in love with her. They brought her over to America, took her around in limousines, and introduced her to everyone."<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2001/mar/10/extract1 "Who pulls the strings?"]</ref> | "the next day she suddenly stood up and launched into a three-minute Thatcher special. I can't remember the topic, but you can imagine. The room was stunned. Here's something for your [[Conspiracy Theorist|conspiracy theorists]]. As a result of that speech, [[David Rockefeller]] and [[Henry Kissinger]] and the other Americans fell in love with her. They brought her over to America, took her around in limousines, and introduced her to everyone."<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2001/mar/10/extract1 "Who pulls the strings?"]</ref> | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | German | + | === UK Prime Minister === |

| + | {{FA|UK/General election/1979}} | ||

| + | In the 1979 UK General election, Margaret Thatcher was elected as UK Prime Minister. Some of the backstory of her success appeared in the German magazine ''[[Der Spiegel]]'' in 1982. They published [[BND]] reports on [[Le Cercle]] (written in late 1979 and early 1980) which outline a "Thatcher faction" within MI6 in the lead-up to the Conservatives' 1979 election victory; a November 1979 report quotes a planning paper by [[Brian Crozier]] about a Cercle complex operation "to affect a change of government in the United Kingdom (accomplished)".<ref name=rogue>http://www.cryptome.org/2012/01/cercle-pinay-6i.pdf</ref><ref>Thatcher was mentioned as a speaker at the [[Cercle]] in a [File:Document-2012-02-21-le-cercle-pinay-document.pdf 2012 invitation letter] from [[Michael Ancram]] to [[Abdulaziz bin Abdullah bin Abdulaziz]].</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | == 1980s == |

| − | + | Thatcher aggressively pushed the [[neoliberal]] agenda of [[privatization]] and was uncompromising in the face of concerted opposition by organised labour, including a bitter [[coal strike]]. | |

| − | + | [[Adam Curtis]]' film ''[[The League of Gentlemen]]'' tells the story of how Thatcher was one of a succession of political leaders who were tempted to believe that "[[the economy]]" was governed by the predictable laws of [[economics]], that their advisers had discovered them and that they would inexorably lead to widespread prosperity.<ref>http://www.unwelcomeguests.net/629_-_Speaking_Forbidden_Truths_(The_Poor_Had_No_Lawyers,_Failure_of_Monetarism)</ref> In fact, social and inequality increased in the UK under the Thatcher governments. Another Curtis film, ''The Mayfair Set'', documents how members of the [[Clermont Club]] rose in fame and fortune during the 1980s. | |

| − | + | === Clockwork Orange cover-up === | |

| − | + | In 1987, Thatcher's government carried out an "[[inquiry]]" into [[Clockwork Orange]], which as ''[[The Guardian]]'' noted in 2006 "concluded the allegations were false, implying that the fading [[Harold Wilson|Wilson]] had descended into [[paranoia]]. This can't be allowed to stand. Not only does it do an injustice to Wilson, it also represents an enormous cover-up."<ref>http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2006/mar/15/comment.labour1</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Foreign policy== | ==Foreign policy== | ||

| Line 84: | Line 92: | ||

===Apartheid Appeaser=== | ===Apartheid Appeaser=== | ||

| − | [[Winston Churchill]] is quoted as saying: "An Appeaser is one who feeds a Crocodile, hoping it will eat him last."<ref>[http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/w/winstonchu100130.html "Winston Churchill quotation"]</ref> | + | [[Winston Churchill]] is quoted as saying: "An Appeaser is one who feeds a Crocodile, hoping it will eat him last."<ref>[http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/w/winstonchu100130.html "Winston Churchill quotation"]</ref> A supporter of apartheid<ref>https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2024/10/who-are-the-terrorists/</ref>, Thatcher adopted the role of "Apartheid Appeaser" in relation to the [[South Africa]]n government led by [[P. W. Botha]] who was also known as "Die Groot Krokodil" (Afrikaans for "The Big Crocodile"). Thatcher called the [[ANC]] a "[[terrorist]]" organisation and branded [[Nelson Mandela]] a "terrorist" and, meanwhile, was active to block the sanctions which most of the world imposed in response to the barbarity of the regime. She once wrote to P. W. Botha: "I have found myself to all intents and purposes alone in resisting sanctions."<ref>[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/margaret-thatcher-branded-anc-terrorist-while-urging-nelson-mandela-s-release-8994191.html "Margaret Thatcher branded ANC ‘terrorist’ while urging Nelson Mandela’s release"]</ref> |

| − | Thatcher | + | Thatcher turned a blind eye to involvement by [[P. W. Botha]]'s [[State Security Council]] in the following: |

*[[Craig Williamson#ANC office in London|The March 1982 bombing of the ANC office in London]] | *[[Craig Williamson#ANC office in London|The March 1982 bombing of the ANC office in London]] | ||

*The assassination of anti-apartheid activist [[Ruth First]] in Maputo, Mozambique on 18 August 1982 | *The assassination of anti-apartheid activist [[Ruth First]] in Maputo, Mozambique on 18 August 1982 | ||

*[[Bernt Carlsson#Burgled in London|The break-in at the London apartment of Socialist International Secretary-General, Bernt Carlsson, in April 1983]] | *[[Bernt Carlsson#Burgled in London|The break-in at the London apartment of Socialist International Secretary-General, Bernt Carlsson, in April 1983]] | ||

*The apartheid regime's possible involvement in the murder of WPC [[Yvonne Fletcher]] on 17 April 1984 | *The apartheid regime's possible involvement in the murder of WPC [[Yvonne Fletcher]] on 17 April 1984 | ||

| − | *The | + | *The assassination of the family of anti-apartheid activist [[Marius Schoon]] in Angola on 28 June 1984 |

| − | *The | + | *The assassination of [[Swedish Prime Minister]] [[Olof Palme]] on 28 February 1986 |

| − | *The | + | *The assassination of President [[Samora Machel]] on 19 September 1986 |

*[[Craig Williamson#ANC leadership|The 1987 plan to kidnap the entire ANC leadership in London]] | *[[Craig Williamson#ANC leadership|The 1987 plan to kidnap the entire ANC leadership in London]] | ||

*The attempted assassination of ANC representative in Brussels, [[Godfrey Motsepe]], on 4 February 1988 | *The attempted assassination of ANC representative in Brussels, [[Godfrey Motsepe]], on 4 February 1988 | ||

| − | *The | + | *The assassination of ANC representative in Paris, [[Dulcie September]], on 29 March 1988 |

*The destruction of [[Pan Am Flight 103]] over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988 | *The destruction of [[Pan Am Flight 103]] over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988 | ||

| − | ====Lunch with P W Botha==== | + | ====Lunch with P. W. Botha==== |

| − | [[File:President_Botha_and_PM_Thatcher.jpg| | + | [[File:President_Botha_and_PM_Thatcher.jpg|333px|thumb|left|[[P. W. Botha]] and Margaret Thatcher at Chequers]] |

| − | On 2 June 1984, Margaret Thatcher controversially invited South Africa's president P W Botha and foreign minister [[Pik Botha]] to a meeting at Chequers in an effort to stave off growing international pressure for the imposition of economic sanctions against South Africa, where both the US and Britain had invested heavily. Although not officially on the meeting's agenda, the [[Coventry Four]] affair clouded both the proceedings at Chequers and Britain's bilateral diplomatic relations with South Africa. On 5 June 1984, Thatcher made a lengthy statement in the [[House of Commons]] about the visit to Chequers by the two Bothas, but she omitted any mention of the [[Coventry Four]] affair:<ref>[http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1984/jun/05/south-african-prime-minister-visit Hansard] 5 June 1984</ref><blockquote>"We had over five hours of discussions. I was accompanied by my right hon. and learned Friend the [[Foreign Secretary]] (Geoffrey Howe) and my hon. Friend the Member for Edinburgh, Pentlands ([[Malcolm Rifkind|Mr Rifkind]]), the Minister of State. The meeting was a working one, and the discussions were comprehensive and candid. They covered the problems of southern Africa as a whole, including Namibia. There was considerable discussion of the internal situation in South Africa. I made clear to [[P W Botha|Mr Botha]] our desire to see peaceful solutions to all the region's problems. On [[Namibia]], we agreed that early independence for Namibia was desirable and should be achieved as soon as possible under peaceful conditions. We also agreed that all foreign forces should be withdrawn from the countries in southern Africa so that their peoples can settle their destinies without outside interference. The withdrawal of South African forces from [[Angola]] is an important first step in this process."</blockquote> | + | On 2 June 1984, Margaret Thatcher controversially invited [[South Africa's president]] P. W. Botha and foreign minister [[Pik Botha]] to a meeting at Chequers in an effort to stave off growing international pressure for the imposition of economic sanctions against South Africa, where both the US and Britain had invested heavily. Although not officially on the meeting's agenda, the [[Coventry Four]] affair clouded both the proceedings at Chequers and Britain's bilateral diplomatic relations with South Africa. On 5 June 1984, Thatcher made a lengthy statement in the [[House of Commons]] about the visit to Chequers by the two Bothas, but she omitted any mention of the [[Coventry Four]] affair:<ref>[http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1984/jun/05/south-african-prime-minister-visit Hansard] 5 June 1984</ref><blockquote>"We had over five hours of discussions. I was accompanied by my right hon. and learned Friend the [[Foreign Secretary]] (Geoffrey Howe) and my hon. Friend the Member for Edinburgh, Pentlands ([[Malcolm Rifkind|Mr Rifkind]]), the Minister of State. The meeting was a working one, and the discussions were comprehensive and candid. They covered the problems of southern Africa as a whole, including Namibia. There was considerable discussion of the internal situation in South Africa. I made clear to [[P W Botha|Mr Botha]] our desire to see peaceful solutions to all the region's problems. On [[Namibia]], we agreed that early independence for Namibia was desirable and should be achieved as soon as possible under peaceful conditions. We also agreed that all foreign forces should be withdrawn from the countries in southern Africa so that their peoples can settle their destinies without outside interference. The withdrawal of South African forces from [[Angola]] is an important first step in this process."</blockquote> |

| + | |||

| + | ====Sanctions: "a tiny little bit"==== | ||

| + | By 1986 the British government was formally committed to four major international agreements on measures against South Africa. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first, adopted in June 1977, is the [[Gleneagles Agreement]] which covers sporting links with South Africa (Appendix I). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, in November 1977, the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Security_Council_Resolution_418 UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 418] which imposed a mandatory embargo on arms to South Africa (Appendix II). (This was extended in December 1984 to cover arms imports from South Africa - but the resolution, UNSCR 558, was not mandatory) (Appendix III). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, in September 1985, EEC Foreign Ministers meeting in Luxembourg agreed on a package of "restrictive measures" (Appendix IV). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, a month later in Nassau, the Prime Minister Mrs Thatcher was a signatory to the [[Commonwealth Accord on Southern Africa]] which included a "programme of common action" (Appendix V). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Commonwealth 'programme of common action' in fact incorporated most of the major elements of the previous agreements. It was the product of a Commonwealth compromise. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Commonwealth leaders had arrived in Nassau for their bi-annual summit on collision course. Since their last Summit the situation in Southern Africa had deteriorated dramatically and almost the entire Commonwealth was convinced of the need for an effective package of Commonwealth sanctions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One Commonwealth leader was resolute in her opposition - Mrs Thatcher. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After hours of confrontation a compromise was struck. A few new measures were agreed. Others were identified for consideration if no progress was forthcoming in South Africa over the next six months. In the meantime an 'Eminent Persons Group' was to be established by the Commonwealth to promote the idea of negotiations between the apartheid regime and genuine leaders of the Black majority. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Within minutes of the agreement having been reached, Mrs Thatcher held a private briefing to which only British journalists were invited. She dismissed the 'programme of common action' and made her now infamous comment, "a tiny little bit; a tiny little bit". Wittingly or unwittingly with those few words she succeeded in humiliating the rest of the Commonwealth by conveying the impression that she had triumphed. Indeed, she even claimed in the [[House of Commons]] on her return that she had achieved "the recognition that economic sanctions would not work", "that many people there (at Nassau) realised that sanctions would be counter-productive", and that "many Heads of Government were pleased that the question of sanctions did not go any further". | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several Commonwealth leaders found it difficult to disguise their anger at Mrs Thatcher's statements. However, they stuck to their part of the Nassau Accord and worked hard to establish the 'Eminent Persons Group'. It eventually reported on 12 June 1986 that there was "no present prospect of a process of dialogue leading to the establishment of a non-racial and representative government."<ref>''[https://www.google.co.uk/search?ei=99UWWtLrK86ugAb1tLfgCA&q=Gleneagles+Agreement+Mrs+Thatcher+%22only+a+tiny+sanction%22&oq=Gleneagles+Agreement+Mrs+Thatcher+%22only+a+tiny+sanction%22&gs_l=psy-ab.12...36851.58992.0.61184.25.25.0.0.0.0.108.1867.24j1.25.0....0...1c.1.64.psy-ab..0.14.1064...33i21k1j33i160k1j33i13i21k1.0.zx3KRmp6sCw "Mrs Thatcher on sanctions: 'a tiny little bit'"]''</ref> | ||

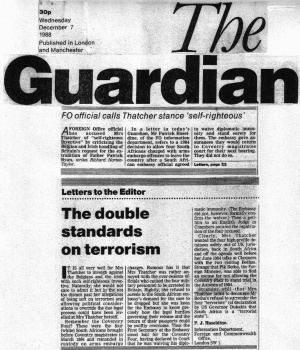

====PM's "double standards on terrorism"==== | ====PM's "double standards on terrorism"==== | ||

| Line 128: | Line 159: | ||

===South African nuke deal=== | ===South African nuke deal=== | ||

| − | [[File:Cameron_and_Thatcher.jpg|240px| | + | [[File:Cameron_and_Thatcher.jpg|240px|left|thumb|South African nuke deal]] |

| − | In what | + | In what critics described as a "sanctions-busting jolly", a youthful [[David Cameron#1989 South Africa trip|David Cameron]] visited [[South Africa]] in 1989 accompanied by Conservative MP, Sir [[Kenneth Warren]] and nuclear weapons inspector, [[Dr David Kelly]], who had made several earlier visits to South Africa when he was given access to the covert nuclear weapons research facility at Pelindaba, near Pretoria.<ref>[http://petereyrepatch.blogspot.co.uk/2010/03/us-and-uk-lost-three-nuclear-weapons_04.html "The US and UK lost three nuclear weapons each! Part 3 - What went missing on Prime Minister Thatcher’s Watch?"]</ref> |

The purpose of Cameron's trip was to arrange for three of South Africa's nuclear weapons to be shipped to [[Oman]], to be stored in case they were required in [[Iraq]]. The remaining six nukes were destined to travel from South Africa to Chicago. The next phase of the operation was that, once the weapons had left South African soil, the UK Government would reimburse the South African firm [[Armscor]] and the British firm [[Astra]] through the middle man [[John Bredenkamp]]. | The purpose of Cameron's trip was to arrange for three of South Africa's nuclear weapons to be shipped to [[Oman]], to be stored in case they were required in [[Iraq]]. The remaining six nukes were destined to travel from South Africa to Chicago. The next phase of the operation was that, once the weapons had left South African soil, the UK Government would reimburse the South African firm [[Armscor]] and the British firm [[Astra]] through the middle man [[John Bredenkamp]]. | ||

| Line 141: | Line 172: | ||

Three months after the [[Pan Am Flight 103|Lockerbie bombing]], Margaret Thatcher and the rising star in Conservative Research Department, [[David Cameron]], visited southern Africa.<ref>[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/revealed-camerons-freebie-to-apartheid-south-africa-1674367.html "Cameron's freebie to apartheid South Africa"]</ref> | Three months after the [[Pan Am Flight 103|Lockerbie bombing]], Margaret Thatcher and the rising star in Conservative Research Department, [[David Cameron]], visited southern Africa.<ref>[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/revealed-camerons-freebie-to-apartheid-south-africa-1674367.html "Cameron's freebie to apartheid South Africa"]</ref> | ||

| − | The then and future Prime Ministers made a point of visiting the [[Rössing Uranium Mine]] in Namibia (occupied by South Africa in defiance of [[UN Security Council]] Resolution 435). | + | The then and future Prime Ministers made a point of visiting the [[Rössing Uranium Mine]] in Namibia (occupied by South Africa in defiance of [[UN Security Council]] Resolution 435). Mrs Thatcher declared it made her "proud to be British", a sentiment echoed by Cameron.<ref>[http://www.radiobridge.net/www/nam/rossing.html "Rössing Uranium Mine"]</ref><ref>[http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2224221/flight_103_it_was_the_uranium.html "Flight 103: It was the Uranium"]</ref> |

| − | + | ==Brighton bombing== | |

| − | + | {{FA|Brighton bombing}} | |

| − | == | + | On 12 October 1984 Prime Minister Thatcher and her cabinet were staying at the Grand Hotel in Brighton for the Conservative Party conference. A bomb exploded which killed five people (including two senior members of the Conservative Party) and injured 31. [[Patrick Magee]] was convicted of the [[Brighton bombing]], sentenced in September 1986 and received seven life sentences. Magee was released from prison in 1999, having served 14 years in prison, under the terms of the [[Good Friday Agreement]].<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/375092.stm "Outrage as Brighton bomber freed"]</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Fall from power== | ==Fall from power== | ||

| Line 181: | Line 183: | ||

==Post Resignation== | ==Post Resignation== | ||

===Philip Morris=== | ===Philip Morris=== | ||

| − | In 1992 Margaret Thatcher signed on as an international consultant to [[Philip Morris]] at a rate of US $500,000 annually, with half to be paid directly to | + | In 1992 Margaret Thatcher signed on as an international consultant to [[Philip Morris]] at a rate of US $500,000 annually, with half to be paid directly to her and half to be paid to the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.<ref>[http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tnu34e00 "Legacy Library Articles"]</ref> ''The Independent'' reported that Philip Morris paid for a 70th birthday bash for Mrs Thatcher on 23 October 1995 in Washington, D.C. with 800 guests attending and at an estimated cost of $1 million. |

===Tax Loophole Exploitation=== | ===Tax Loophole Exploitation=== | ||

| Line 187: | Line 189: | ||

Thatcher's home was estimated to be worth at least £2.5m. As she was not the registered owner she has potentially avoided at least £100,000 in stamp duty and £900,000 in inheritance tax.<ref>Rob Evans and David Hencke, [http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2002/may/25/tax.politics "Tax loopholes on homes benefit the rich and cost UK millions: Choice homes, virtually tax free"], ''The Guardian'', 25th May 2002</ref> | Thatcher's home was estimated to be worth at least £2.5m. As she was not the registered owner she has potentially avoided at least £100,000 in stamp duty and £900,000 in inheritance tax.<ref>Rob Evans and David Hencke, [http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2002/may/25/tax.politics "Tax loopholes on homes benefit the rich and cost UK millions: Choice homes, virtually tax free"], ''The Guardian'', 25th May 2002</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===''The Downing Street Years''=== | ||

| + | {{FA|The Downing Street Years}} | ||

| + | Margaret Thatcher's autobiography, ''The Downing Street Years'', was accompanied by a four-part [[BBC]] television series of the same name. | ||

==Death== | ==Death== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:03, 21 October 2024

Margaret Hilda Thatcher was a UK deep state functionary who after attending the 1975 Bilderberg experienced a Bilderberg boost and was appointed leader of the UK Conservative Party. In 1979 she was made UK Prime Minister after action by the Shield committee, a job she retained until 1990. A Soviet journalist called her "The Iron Lady", a nickname which became associated with her uncompromising politics and leadership style. As Prime Minister, she faithfully implemented neoliberal economic policies of privatisation for her UK deep state masters (dubbed "Thatcherism" by the commercially-controlled media).[1] After retiring from the House of Commons, Thatcher was ennobled in 1992 as Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven in the county of Lincolnshire, which entitled her to sit in the House of Lords.[2]

Contents

1970s

The 11th February 1975 brought the highpoint of a long campaign which deposed Edward Heath as Leader of the Conservative Party, replacing him by his former Education Secretary, the relatively unknown Thatcher. After the intervention of Brian Crozier's Shield[4] she prevailed against William Whitelaw by 146 votes to 79.[5] Her campaign was run by her private secretary, Tory MP and former MI6 officer Airey Neave, who was assassinated by a car bomb on 30 March 1979 before he could assume the post of Northern Ireland Secretary.

1975 Bilderberg

Denis Healey (then Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Labour Party government) recalls that he invited Thatcher to the 1975 Bilderberg conference and that after listening in silence for two days:

"the next day she suddenly stood up and launched into a three-minute Thatcher special. I can't remember the topic, but you can imagine. The room was stunned. Here's something for your conspiracy theorists. As a result of that speech, David Rockefeller and Henry Kissinger and the other Americans fell in love with her. They brought her over to America, took her around in limousines, and introduced her to everyone."[6]

UK Prime Minister

- Full article: UK/General election/1979

- Full article: UK/General election/1979

In the 1979 UK General election, Margaret Thatcher was elected as UK Prime Minister. Some of the backstory of her success appeared in the German magazine Der Spiegel in 1982. They published BND reports on Le Cercle (written in late 1979 and early 1980) which outline a "Thatcher faction" within MI6 in the lead-up to the Conservatives' 1979 election victory; a November 1979 report quotes a planning paper by Brian Crozier about a Cercle complex operation "to affect a change of government in the United Kingdom (accomplished)".[5][7]

1980s

Thatcher aggressively pushed the neoliberal agenda of privatization and was uncompromising in the face of concerted opposition by organised labour, including a bitter coal strike.

Adam Curtis' film The League of Gentlemen tells the story of how Thatcher was one of a succession of political leaders who were tempted to believe that "the economy" was governed by the predictable laws of economics, that their advisers had discovered them and that they would inexorably lead to widespread prosperity.[8] In fact, social and inequality increased in the UK under the Thatcher governments. Another Curtis film, The Mayfair Set, documents how members of the Clermont Club rose in fame and fortune during the 1980s.

Clockwork Orange cover-up

In 1987, Thatcher's government carried out an "inquiry" into Clockwork Orange, which as The Guardian noted in 2006 "concluded the allegations were false, implying that the fading Wilson had descended into paranoia. This can't be allowed to stand. Not only does it do an injustice to Wilson, it also represents an enormous cover-up."[9]

Foreign policy

Margaret Thatcher was proud of her support for Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator installed by the CIA.[10]

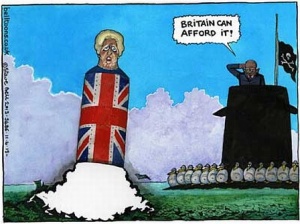

Apartheid Appeaser

Winston Churchill is quoted as saying: "An Appeaser is one who feeds a Crocodile, hoping it will eat him last."[11] A supporter of apartheid[12], Thatcher adopted the role of "Apartheid Appeaser" in relation to the South African government led by P. W. Botha who was also known as "Die Groot Krokodil" (Afrikaans for "The Big Crocodile"). Thatcher called the ANC a "terrorist" organisation and branded Nelson Mandela a "terrorist" and, meanwhile, was active to block the sanctions which most of the world imposed in response to the barbarity of the regime. She once wrote to P. W. Botha: "I have found myself to all intents and purposes alone in resisting sanctions."[13]

Thatcher turned a blind eye to involvement by P. W. Botha's State Security Council in the following:

- The March 1982 bombing of the ANC office in London

- The assassination of anti-apartheid activist Ruth First in Maputo, Mozambique on 18 August 1982

- The break-in at the London apartment of Socialist International Secretary-General, Bernt Carlsson, in April 1983

- The apartheid regime's possible involvement in the murder of WPC Yvonne Fletcher on 17 April 1984

- The assassination of the family of anti-apartheid activist Marius Schoon in Angola on 28 June 1984

- The assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme on 28 February 1986

- The assassination of President Samora Machel on 19 September 1986

- The 1987 plan to kidnap the entire ANC leadership in London

- The attempted assassination of ANC representative in Brussels, Godfrey Motsepe, on 4 February 1988

- The assassination of ANC representative in Paris, Dulcie September, on 29 March 1988

- The destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988

Lunch with P. W. Botha

On 2 June 1984, Margaret Thatcher controversially invited South Africa's president P. W. Botha and foreign minister Pik Botha to a meeting at Chequers in an effort to stave off growing international pressure for the imposition of economic sanctions against South Africa, where both the US and Britain had invested heavily. Although not officially on the meeting's agenda, the Coventry Four affair clouded both the proceedings at Chequers and Britain's bilateral diplomatic relations with South Africa. On 5 June 1984, Thatcher made a lengthy statement in the House of Commons about the visit to Chequers by the two Bothas, but she omitted any mention of the Coventry Four affair:[14]

"We had over five hours of discussions. I was accompanied by my right hon. and learned Friend the Foreign Secretary (Geoffrey Howe) and my hon. Friend the Member for Edinburgh, Pentlands (Mr Rifkind), the Minister of State. The meeting was a working one, and the discussions were comprehensive and candid. They covered the problems of southern Africa as a whole, including Namibia. There was considerable discussion of the internal situation in South Africa. I made clear to Mr Botha our desire to see peaceful solutions to all the region's problems. On Namibia, we agreed that early independence for Namibia was desirable and should be achieved as soon as possible under peaceful conditions. We also agreed that all foreign forces should be withdrawn from the countries in southern Africa so that their peoples can settle their destinies without outside interference. The withdrawal of South African forces from Angola is an important first step in this process."

Sanctions: "a tiny little bit"

By 1986 the British government was formally committed to four major international agreements on measures against South Africa.

The first, adopted in June 1977, is the Gleneagles Agreement which covers sporting links with South Africa (Appendix I).

Then, in November 1977, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 418 which imposed a mandatory embargo on arms to South Africa (Appendix II). (This was extended in December 1984 to cover arms imports from South Africa - but the resolution, UNSCR 558, was not mandatory) (Appendix III).

Then, in September 1985, EEC Foreign Ministers meeting in Luxembourg agreed on a package of "restrictive measures" (Appendix IV).

Finally, a month later in Nassau, the Prime Minister Mrs Thatcher was a signatory to the Commonwealth Accord on Southern Africa which included a "programme of common action" (Appendix V).

The Commonwealth 'programme of common action' in fact incorporated most of the major elements of the previous agreements. It was the product of a Commonwealth compromise.

Commonwealth leaders had arrived in Nassau for their bi-annual summit on collision course. Since their last Summit the situation in Southern Africa had deteriorated dramatically and almost the entire Commonwealth was convinced of the need for an effective package of Commonwealth sanctions.

One Commonwealth leader was resolute in her opposition - Mrs Thatcher.

After hours of confrontation a compromise was struck. A few new measures were agreed. Others were identified for consideration if no progress was forthcoming in South Africa over the next six months. In the meantime an 'Eminent Persons Group' was to be established by the Commonwealth to promote the idea of negotiations between the apartheid regime and genuine leaders of the Black majority.

Within minutes of the agreement having been reached, Mrs Thatcher held a private briefing to which only British journalists were invited. She dismissed the 'programme of common action' and made her now infamous comment, "a tiny little bit; a tiny little bit". Wittingly or unwittingly with those few words she succeeded in humiliating the rest of the Commonwealth by conveying the impression that she had triumphed. Indeed, she even claimed in the House of Commons on her return that she had achieved "the recognition that economic sanctions would not work", "that many people there (at Nassau) realised that sanctions would be counter-productive", and that "many Heads of Government were pleased that the question of sanctions did not go any further".

Several Commonwealth leaders found it difficult to disguise their anger at Mrs Thatcher's statements. However, they stuck to their part of the Nassau Accord and worked hard to establish the 'Eminent Persons Group'. It eventually reported on 12 June 1986 that there was "no present prospect of a process of dialogue leading to the establishment of a non-racial and representative government."[15]

PM's "double standards on terrorism"

On 7 December 1988, British diplomat Patrick Haseldine wrote a letter to The Guardian criticising Margaret Thatcher for her "double standards on terrorism":

Text of Haseldine's letter:[16][17][18][19]

"It is all very well for Mrs Thatcher to inveigh against the Belgians and the Irish with such self-righteous invective. Naturally, she would not care to admit it but in the not too distant past her allegations of being soft on terrorism and allowing political considerations to override the due legal process could have been levelled at Mrs Thatcher herself. Remember the "Coventry Four"? These were the four (white) South Africans brought before Coventry magistrates in March 1984 and remanded in custody on arms embargo charges. Rumour has it that Mrs Thatcher was rather annoyed with the over-zealous officials who caused the four military personnel to be arrested in Britain. Rightly, she refused to accede to the South African embassy's demand for the case to be dropped but she was keen for the embassy to know precisely how the legal hurdles governing their release and the return of their passports could be swiftly overcome. Thus the First Secretary at the embassy stood bail for the "Coventry Four", having declared in court that he was waiving his diplomatic immunity. (The embassy did not, however, formally confirm the waiver.) Then a petition to an English Judge in Chambers secured the repatriation of the four accused. Clearly, Mrs Thatcher wanted the four high-profile detainees safely out of UK jurisdiction, back in South Africa and off the agenda well before her June 1984 talks at Chequers with the two visiting Bothas (P W Botha and Pik Botha). Strange that Pik Botha, the foreign minister, was able to find an excuse for not allowing the "Coventry Four" to stand trial in the Autumn of 1984. Stranger still that Mrs Thatcher failed to denounce Mr Botha's refusal to surrender the four 'terrorists' (cf declaration by U.S. Governor Dukakis that South Africa is a "terrorist state").[20]

Conspiracy with Reagan

On 2 December 2010, in a video conference link to staff and students at the London School of Economics, Muammar Gaddafi alleged that the case against Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi had 'been fabricated and created by' Britain's former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and former US President Ronald Reagan. He suggested that the CIA had been behind the 21 December 1988 Lockerbie bombing which killed 270 people.

"These are the people who created this conspiracy" said Gaddafi, referring to the alleged role of Thatcher and Reagan in Megrahi's conviction and life sentence over the attack on Pan Am Flight 103. "The charges directed towards Libya were based on unfounded evidence in an attempt to weaken the Libyan Revolution and limit its resources and abilities".[21]

In making his allegation, Gaddafi did not include George H W Bush. This may suggest that if Thatcher and Reagan had indeed 'fabricated and created' the Lockerbie bombing case against Libya, they would have done so in the interregnum between the 8 November 1988 US presidential election and President Bush taking over from Reagan on 20 January 1989.

Gaddafi's alleged Lockerbie conspiracy could well have been hatched on 15 November 1988 when President Reagan and Prime Minister Thatcher were photographed in the White House library and would undoubtedly have discussed Iran's threat to retaliate massively for the shooting down of Iran Air Flight 655 by USS Vincennes on 3 July 1988 with the loss of 290 civilian lives.

The two leaders might then have decided to open secret negotiations with Iran and seek to limit the revenge attack to just one US aircraft. The US and UK would not have wanted to antagonise the Iranians further by blaming Iran for the retaliation, so would have selected 'mad dog' Gaddafi to be their whipping boy. Western intelligence agencies (including apartheid South Africa's National Intelligence Service) would have been party to such negotiations and would have had a say in selecting the sacrificial aircraft.

Thus on 22 December 1988 (the day after the Lockerbie bombing), President Reagan phoned Downing Street:

- "Margaret, I understand you have just returned from the site of the Pan Am crash. I want to thank you for your expression of sorrow on the Pan Am 103 tragedy. On behalf of the American people, I also want to thank the rescue workers who responded so quickly and courageously. Our thoughts and prayers are with the victims of this accident, both the passengers on the plane and the villagers in Scotland."[22][23]

On 28 December 1988, seven days after the Lockerbie bombing, when there was as yet no evidence ostensibly pointing to Libyan culpability, in one of the last acts of his Presidency, Ronald Reagan extended sanctions against Libya and threatened renewed bombing raids.[24] The joint US/UK investigation into the bombing soon found 'evidence' pointing towards Libya for the sabotage of Pan Am Flight 103. According to author and journalist, Ian Ferguson, it was a case of 'reverse engineering' whereby Libya had been fitted up for the crime and the inculpatory evidence followed (see the 2009 documentary film Lockerbie Revisited).[25]

South African nuke deal

In what critics described as a "sanctions-busting jolly", a youthful David Cameron visited South Africa in 1989 accompanied by Conservative MP, Sir Kenneth Warren and nuclear weapons inspector, Dr David Kelly, who had made several earlier visits to South Africa when he was given access to the covert nuclear weapons research facility at Pelindaba, near Pretoria.[26]

The purpose of Cameron's trip was to arrange for three of South Africa's nuclear weapons to be shipped to Oman, to be stored in case they were required in Iraq. The remaining six nukes were destined to travel from South Africa to Chicago. The next phase of the operation was that, once the weapons had left South African soil, the UK Government would reimburse the South African firm Armscor and the British firm Astra through the middle man John Bredenkamp.

At Government level it would be dealt with primarily by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) using Ministry of Defence money. To keep this out of Parliament and out of the public domain, Thatcher reportedly signed off these weapons (just before leaving office in late 1990) under a special Urgent Operational Requirement (UOR) - describing them as metal cylinders rather than nuclear bombs.[27]

In April 2010, it was reported that £17.8 million from this secret nuclear deal found its way into Conservative Party funds.[28]

"Proud to be British"

Three months after the Lockerbie bombing, Margaret Thatcher and the rising star in Conservative Research Department, David Cameron, visited southern Africa.[29]

The then and future Prime Ministers made a point of visiting the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia (occupied by South Africa in defiance of UN Security Council Resolution 435). Mrs Thatcher declared it made her "proud to be British", a sentiment echoed by Cameron.[30][31]

Brighton bombing

- Full article: Brighton bombing

- Full article: Brighton bombing

On 12 October 1984 Prime Minister Thatcher and her cabinet were staying at the Grand Hotel in Brighton for the Conservative Party conference. A bomb exploded which killed five people (including two senior members of the Conservative Party) and injured 31. Patrick Magee was convicted of the Brighton bombing, sentenced in September 1986 and received seven life sentences. Magee was released from prison in 1999, having served 14 years in prison, under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.[32]

Fall from power

Bilderberg specialist Jim Tucker attributes her downfall to a decision made at a meeting of the Bilderberg group, because she refused to allow British sovereignty to be dismantled. When Tucker asked her about it, he reports she whispered back that she considered it a "great tribute to be denounced by Bilderberg".[33]

Post Resignation

Philip Morris

In 1992 Margaret Thatcher signed on as an international consultant to Philip Morris at a rate of US $500,000 annually, with half to be paid directly to her and half to be paid to the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.[34] The Independent reported that Philip Morris paid for a 70th birthday bash for Mrs Thatcher on 23 October 1995 in Washington, D.C. with 800 guests attending and at an estimated cost of $1 million.

Tax Loophole Exploitation

In an article in 2002 on the subject of how 'Rich people are costing Britain millions in lost tax by not registering their houses in their own names', the Guardian[35] reported that Thatcher's home in Chester Square, London was registered as owned by Bakeland Property Ltd, Jersey. It was acquired in 1991 and Thatcher has it on 64-year lease. The shares for Bakeland Property Ltd are held by two Jersey individuals (Leonard Day and Hugh Thurston) who are the Thatcher family's financial advisers. According to the report, they are 'acting as nominees for a trust with concealed beneficiaries'. The former prime minister's office is reported to have refused to explain why she does not apparently own her own house. Leonard Day in Jersey is reported to have said: "No one's going to tell you about that." The article claims that through the exploitation of legal loopholes 'wealthy individuals... appear to be enjoying the country's choicest property virtually tax-free'. The article also mentions Anthony Tabatznik, Mohamed Al Fayed, David Potter, Tony Tabatznik, Lakshmi Mittal, Uri David, Rupert Allason, Wafic Said, Prince Bandar and Christopher Ondaatje as others who are not the registered owners of their homes who may benefit from such a loophole.

Thatcher's home was estimated to be worth at least £2.5m. As she was not the registered owner she has potentially avoided at least £100,000 in stamp duty and £900,000 in inheritance tax.[36]

The Downing Street Years

- Full article: The Downing Street Years

- Full article: The Downing Street Years

Margaret Thatcher's autobiography, The Downing Street Years, was accompanied by a four-part BBC television series of the same name.

Death

Margaret Thatcher died on 8 April 2013. That day a Buckingham Palace spokesman said:

- "The Queen was sad to hear the news of the death of Baroness Thatcher. Her Majesty will be sending a private message of sympathy to the family."[37]

Lady Thatcher's ceremonial funeral with a "Falklands War theme" at St Paul's Cathedral in London on 17 April 2013 has been estimated to cost £10 million.[38]

South African ex-minister and ex-ANC activist Pallo Jordan did not attend her funeral. He told the Guardian:

- "I say good riddance. She was a staunch supporter of the apartheid regime".

Jordan accompanied Nelson Mandela on a visit to London in 1991, which included a meeting with Thatcher:

- "Although she called us a terrorist organisation, she had to shake hands with a terrorist and sit down with a terrorist. So who won?"[39]

Appointments by Margaret Thatcher

| Appointee | Job | Appointed | End | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percy Cradock | UK/Joint Intelligence Committee/Chair | 1985 | 1992 | |

| Nicholas Fairbairn | Solicitor General for Scotland | 1979 | 1982 | Also UK/VIPaedophile |

| Peter Fraser | Solicitor General for Scotland | 1982 | 1989 | |

| Michael Havers | Lord Chancellor | 13 June 1987 | 26 October 1987 | |

| Michael Havers | Attorney General for Northern Ireland | 6 May 1979 | 13 June 1987 | |

| Michael Havers | Attorney General for England and Wales | 6 May 1979 | 13 June 1987 | |

| Ian MacGregor | British Steel Corporation/Chairman | 1980 | 1983 | Paid |

| Ian MacGregor | National Coal Board/Chairman | 1983 | 1986 | During the Miners' Strike |

Related Quotations

| Page | Quote | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tony Blair | “Thatcher deliberately and cruelly wrecked the social democratic society in which I grew up, with the aim of destroying any ability for working people to be protected against the whims of the wealthy. But Thatcher never introduced privatisation into the NHS or state schools – that was her acolyte Blair. She maintained free university education in England and Wales. That was destroyed by Blair too.” | Craig Murray Tony Blair | 25 July 2019 |

| Yuriko Koike | “I have received the enthusiastic support of my colleagues. In order to break through the deadlock facing Japanese society, I believe the country might as well have a female candidate. Hillary used the word 'glass ceiling' ... but in Japan, it isn't glass, it's an iron plate. I'm not Mrs. Thatcher, but what is needed is a strategy that advances a cause with conviction, clear policies and sympathy with the people."” | Yuriko Koike | 8 September 2008 |

| Leader of the Conservative Party | “All Tory leaders have surrounded themselves with an inner circle, which has given them ballast and in certain important respects defined their leadership. John Major had a winning fondness for palpable fakes, like Jeffrey Archer and David Mellor; Margaret Thatcher liked hirsute North London entrepreneurs with a ‘can-do’ attitude and heavy jewellery. Michael Howard’s chosen milieu is constructed of dapper, well-spoken men and women, many of whom live within walking distance of one another in west London. Cameron is unmistakably the leader of these Notting Hill Tories, but others include Michael Howard’s political secretary Rachel Whetstone, his speechwriter Ed Vaizey, marketing expert Steve Hilton, policy man Nick Boles, along with the newspaper columnists Edward Heathcoat Amory and his wife Alice Thomson.” | Peter Oborne | 19 June 2004 |

Events Participated in

| Event | Start | End | Location(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilderberg/1975 | 25 April 1975 | 27 April 1975 | Turkey Golden Dolphin Hotel Cesme | The 24th Bilderberg Meeting, 98 guests |

| Bilderberg/1986 | 25 April 1986 | 27 April 1986 | Scotland Gleneagles Hotel | The 34th Bilderberg, 109 participants |

Related Documents

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:How Megrahi and Libya were framed for Lockerbie | article | 22 July 2010 | Alexander Cockburn | |

| Document:How to Keep Going During the Next Energy Crisis | Article | 25 September 2021 | Mike Small | The social chaos unwinding on your forecourts and timelines is the long-term consequence of decades of privatisation, core industries run for profiteering with no thinking about the socio-ecological consequence. As people face mass fuel poverty, the dark irony is that all of these “British” institutions were sold off by the Tories, now desperate to defend the very concept of Britishness they’ve sold. |

| Document:Maggie's Guilty Secret | article | December 2013 | John Hughes-Wilson | A brief resume of the Arms-to-Iraq affair by a former colonel on NATO's international political staff in Brussels. It revisits the abortive rescue of US diplomatic staff held hostage by Iran under President Carter, paving the way for the UK to supply arms to both sides in the soon-to-follow Iran-Iraq war in covert defiance of UN sanctions. The UK establishment has been engaged in a monumental cover-up ever since. |

| Document:Margaret Thatcher Ruined Britain | blog post | 30 December 2021 | Clifford Thurlow | Margaret Thatcher ruined Britain with her hard-right policies and the five Conservative prime ministers, since her party knifed her in the back the Tory way, have carelessly kicked over the remains. Each has been worse than the last in descending order – John Major, David Cameron, Theresa May, liar Boris Johnson and finally Liz Truss, a puppet with a wooden heart and personal photographer. |

| Document:Memo To Prime Minister - Your Merchants of Death Are Cooking The Books | article | 17 October 1980 | Duncan Campbell | |

| Document:PT35B - The Most Expensive Forgery in History | Article | 18 October 2017 | Ludwig De Braeckeleer | Ludwig De Braeckeleer proves that the Lockerbie bomb timer fragment PT/35(b) is a "fragment of the imagination" |

| Document:Pan Am Flight 103: It was the Uranium | article | 6 January 2014 | Patrick Haseldine | Following Bernt Carlsson's untimely death in the Lockerbie bombing, the UN Council for Namibia inexplicably dropped the case against Britain's URENCO for illegally importing yellowcake from the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia. |

| Document:The Crime of Lockerbie | Article | 16 August 2009 | Tam Dalyell | Tam Dalyell said: "Yes, I have read 'The Downing Street Years' very carefully. Why in 800 pages did you not mention Lockerbie once?" Mrs Thatcher replied: "Because I didn’t know what happened and I don’t write about things that I don’t know about." |

| Document:The great con that ruined Britain | Article | 3 April 2016 | Peter Hitchens | Peter Hitchens, the repentant Thatcherite, has second thoughts about privatisation: if it’s all been so beneficial, why do so many of the containers that arrive in British ports, full of expensive imports, leave this country empty? |

References

- ↑ "The Great NHS Heist Documentary"

- ↑ "Biography of Margaret Thatcher"

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph, London, Greater London, England, 28 Dec 2012, Fri, Page 5

- ↑ A group set up quite possibly with the express purpose of getting her elected

- ↑ a b http://www.cryptome.org/2012/01/cercle-pinay-6i.pdf

- ↑ "Who pulls the strings?"

- ↑ Thatcher was mentioned as a speaker at the Cercle in a [File:Document-2012-02-21-le-cercle-pinay-document.pdf 2012 invitation letter] from Michael Ancram to Abdulaziz bin Abdullah bin Abdulaziz.

- ↑ http://www.unwelcomeguests.net/629_-_Speaking_Forbidden_Truths_(The_Poor_Had_No_Lawyers,_Failure_of_Monetarism)

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2006/mar/15/comment.labour1

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/tories-have-forgotten-that-thatcher-wasnt-just-a-terrorist-sympathiser-but-close-friends-with-one-10507850.html?icn=puff-8

- ↑ "Winston Churchill quotation"

- ↑ https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2024/10/who-are-the-terrorists/

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher branded ANC ‘terrorist’ while urging Nelson Mandela’s release"

- ↑ Hansard 5 June 1984

- ↑ "Mrs Thatcher on sanctions: 'a tiny little bit'"

- ↑ "Letter to The Guardian December 7, 1988"

- ↑ "Fresh facts support PM's critic"

- ↑ "Sacked Thatcher critic sues ministry"

- ↑ "European Court of Human Rights, Patrick Haseldine vs United Kingdom"

- ↑ "Dukakis Backers Agree Platform Will Call South Africa 'Terrorist'"

- ↑ "Lockerbie bomber's family preparing to sue Britain for false imprisonment"

- ↑ "Reagan phone call to Thatcher at Downing Street"

- ↑ "Secret papers show Thatcher's cabinet ruled out public inquiry within hours of Lockerbie bombing"

- ↑ "Exploding Lockerbie – Part 2"

- ↑ "Lockerbie conspiracy by Thatcher and Reagan"

- ↑ "The US and UK lost three nuclear weapons each! Part 3 - What went missing on Prime Minister Thatcher’s Watch?"

- ↑ "The US and UK lost three nuclear weapons each! Part 4 - What went missing on Prime Minister Thatcher’s Watch?"

- ↑ "UK’s Electoral Commission to investigate Friends of Israel Groups"

- ↑ "Cameron's freebie to apartheid South Africa"

- ↑ "Rössing Uranium Mine"

- ↑ "Flight 103: It was the Uranium"

- ↑ "Outrage as Brighton bomber freed"

- ↑ "Behind closed doors: the power and influence of secret societies" p. 169.

- ↑ "Legacy Library Articles"

- ↑ Evans, R & Hencke, D. (2002) 'Tax loopholes on homes benefit the rich and cost UK millions'. The Guardian 25th May 2002. Accessed 22nd May 2008

- ↑ Rob Evans and David Hencke, "Tax loopholes on homes benefit the rich and cost UK millions: Choice homes, virtually tax free", The Guardian, 25th May 2002

- ↑ "Ex-Prime Minister Baroness Thatcher dies, aged 87"

- ↑ "Guess who is not coming to Margaret Thatcher's funeral"

- ↑ "Thatcher mourned by few in South Africa"