Document:Memo To Prime Minister - Your Merchants of Death Are Cooking The Books

Subjects: International Military Services, Margaret Thatcher, Arm Deals

Source: New Statesman (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Memo To Prime Minister:- Your Merchants of Death Are Cooking The Books

Mrs. Thatcher, boosting the nationalised arms business, imagines it's profitable. DUNCAN CAMPBELL, aided by a mole, shows her she's wrong.

The Bribe Machine

Mrs Thatcher has publicly endorsed the efforts of Britain's arms salesmen, headed by the Ministry of Defence's own company - International Military Services Ltd. But IMS's business is bad, and prospects poor.

- Their business is failing. So IMS has doctored its accounts to turn a £½ million loss into a £6 million profit.

- The Directors of IMS have probably broken the Companies Acts.

- They have acted in the arms business as a channel for giving bribes or special 'commissions'.

- As recently as January, a payment of £½ million was made by IMS to a secret codenamed Swiss bank account.

- If IMS makes a loss, the taxpayer pays up. Yet the Ministry of Defence want more public money put into loss-making arms dealing.

- The company and the Ministry have hidden away £300 million of Iranian money which they don't intend to pay back.

DUNCAN CAMPBELL reveals, with the aid of defence industry 'moles' , the tawdry inside story of IMS and the arms dealers. Research by DAVID POYSER.

THE STORY OF BRITAIN'S arms dealers has, for the last ten years, been the story of the Shah of Iran, his imperial ambitions, and his corrupt and militarist regime. Most of the deals with the Shah of Iran were in the hands of a little known but significant government owned company - originally called Millbank Technical Services (MTS); a progeny of the Crown Agents, but latterly owned and run by Military Services Ltd. This company is the lynchpin of a new strategy for selling yet more weapons abroad - a strategy Mrs Thatcher acclaimed at a recent dinner when she feted the £1.2 billion worth of arms and accessories that the MoD say will go abroad this year. Mrs Thatcher told the dinner: "it's a handy sum, it's quite a large sum. But, gentlemen, it is not enough."

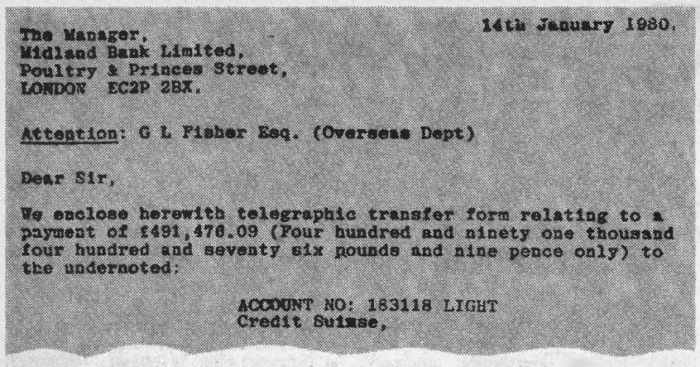

The New Statesman has evidence that much of MTS/IMS's task has been the bribery, directly or indirectly, of overseas government officials. In the last three years, we have evidence of £2.5 million worth of such 'commission' payments. As recently as January this year, IMS sent £491,000 to a codenamed and numbered bank account in Switzerland. The company have offered no explanation of how this payment fits in with their normal trading - which involves paying British firms for goods, and selling those abroad.

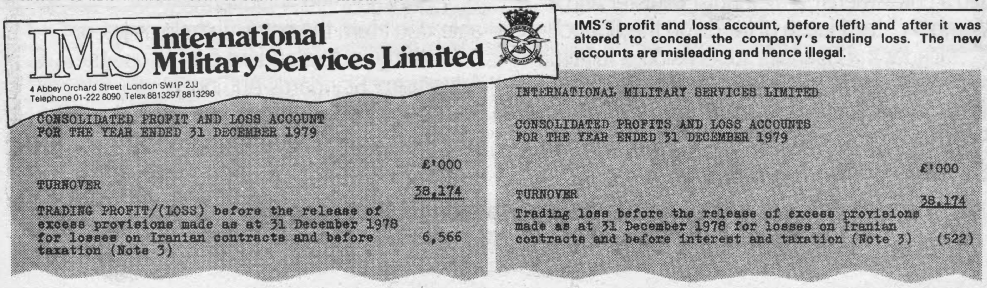

The New Statesman also has firm evidence that IMS's latest annual accounts for 1979 - which were filed at Companies House during August - have been cooked up to present a misleading impression to parliament and the public. In draft accounts produced for IMS management in April 1980, and a copy of which we have, IMS showed a trading loss of £522,000. By the time these were published in August, this had become a trading profit of £6.566 million, a remarkable change. This apparent turnaround in IMS's fortunes was achieved by removing from the accounts all reference to some £7 million of interest that IMS had received from banking clients' and creditors' money.

These alterations have two effects. First, they might have helped to convince doubting MPs who the MoD had shortly hoped would back a Defence Sales Bill, and in particular the vigilant Public Accounts Committee, that IMS is doing well, and that selling weaponry is sufficiently profitable to overcome awkward moral scruples. Secondly, IMS and the Ministry of Defence are extremely anxious to conceal that they have about £300 million of the Iranian government's money, paid in advance for tanks which have not reached and will not reach Iran. The tanks - called Shir Iran and based on the British Army's Chieftain - were being produced before the revolution. The Ministry of Defence will be claiming for losses on the cancelled contract but even elastic official accountancy will not stretch their claims as far as the £300 million which they - and IMS - have now got sitting in the bank. Official documents which we have seen show that the MoD has no intention of handing any of it back to the Iranians, and consequently the money has just been sifted away from IMS's published accounts. The MoD refuse to say how large the termination claims may be, stressing that hundreds of subcontractors are involved. They wish to pocket any cash left over.

DESPITE MRS THATCHER's enthusiasm for the arms trade, and the official plans for developing IMS, at the moment the arms business is extremely depressed. IMS's turnover, which rose through the 1970s to over £250 million in 1978, was a mere £38 million in 1979. It will be only slightly more this year. They have cut staff back from over 700 to 135. At the beginning of the year, their only customers were Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Morocco and Kuwait. Iran had by 1977 provided 95 per cent of MTS/IMS's turnover and even more of its profit. With Iran gone IMS made a loss of £12½ million in 1978 and, as the confidential draft accounts show (see page 12), a £½ million trading loss in 1979.

To help bolster IMS's sagging turnover, the MoD has recently given the company exclusive rights to sell the guns and ammunition made by the Royal Ordnance Factories. The new arrangement also helps put bribes, 'commissions' and 'consultancy' rackets at second hand to the MoD, whose own forays into the weapons business have been less than successful: in 1977 the Public Accounts Committee discovered that the MoD was losing on its weapon sales because they did not make sure that their customers paid up.

IMS's new work has been taken over from the MoD's existing Defence Sales Organisation, who' have also been ordered to get all business they can for IMS. One former middle eastern government official who has been approached by IMS told us:

- Their brochure would have breached the Trades Description Act in Britain. It was full of pictures

of British defence establishments which IMS claimed they had the skills to build. But they had never done any of it.

IMS have failed to win recent business or confidence in Britain's other middle eastern client state, Oman. But, two large contracts have turned up to salve IMS's fortunes slightly. Some of the Shir Iran (modified Chieftain) tanks which the Iranians didn't want any more have been sold to Jordan. And in January, Saudi Arabia signed a contract worth between £50 and £100 million for unspecified defence equipment. The Jordanian tank deal includes about 20 armoured recovery vehicles originally intended for the Shah at £720,000 each. The Jordanians have received this job lot at the 'bargain' price of £850,000 each.

More seriously, there is the question of who received £490,000 from IMS in January of this year. A letter in the New Statesman's possession (see left) shows that IMS's finance director, Patrick Mooney, ordered the payment from the Midland Bank to Credit Suisse in Zurich on 14 January 1980. The money went into a numbered account - no 183118 - which had the codename 'LIGHT'.

Since none of IMS's major suppliers are abroad, this payment is wholly unusual. It follows directly the signing of the Saudi Arabian contract, and comes two months after the Jordanian contract. Both contracts are worth about £100 million. Business experts to whom we have shown these particulars have little doubt that the payment is a secret 'commission' which, when passed on to the customary group' of generals becomes, unequivocally, a 'bribe'.

We asked IMS last week specifically and separately whether they would acknowledge making the payment and whether it was a commission for Saudi agents. They replied:

- In order to maintain the accepted standards of commercial confidentiality, the Company does not answer questions about detailed specific transactions.

IMS denied the payment was connected with the Saudi Arabian contract but have refused to say with what it is connected. It is, perhaps, a matter that both the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons - and the Saudi government - may wish to investigate. The Saudis would be particularly sensitive, as their contract specifically proscribes 'contingent' fees or bribes! Clause 13 of the contract threatens that the "Contract shall be terminated and the Contractor's name shall be crossed out from the list of approved contractors" if a bribe, "directly or indirectly" reaches a concerned Saudi government official.

IN REALITY, bribery is entrenched in the weapons business and few, if any, contracts are struck without the accompanying payments sideways to Swiss bank accounts. IMS claimed to us last week that, as a British government organisation, they would never pay bribes. This claim is directly contradicted by evidence given by Sir Lester Suffield, former head of the MoD's Defence Sales Organisation, who admitted in a 1978 corruption case that MTS and the MoD had offered payments to government officials on at least one occasion which he claimed was, however, "not carried out".

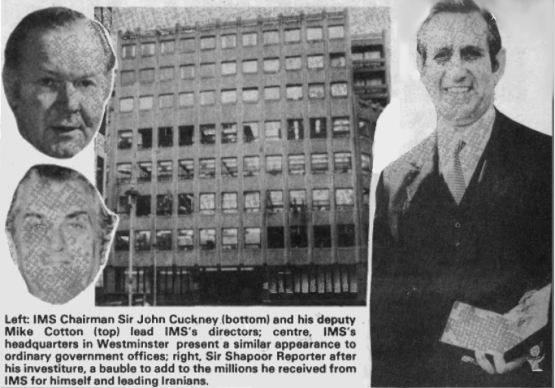

One businessman who worked closely with MTS in the Middle East had a different, succinct view of their original role; they had to "payoff top-level officials" which meant, in Iran, paying at least one per cent of every Iranian contract to Sir Shapoor Reporter, who lubricated the path of every arms deal with Iran by acting as a conduit for payments to the Shah's Pavlahvi Fund and elsewhere. While MTS paid off the top people, the British firms involved also had the use of "King Street facilities" - a reference to the use of the Foreign Office's diplomatic bag for transferring necessary suitcases of cash to payoff lower level officials.

Until the early 1970s, MTS were a very different sort of business to their present day successor, International Military Services. They were selling, in 1970, sewage systems to Uganda, vehicles to Jamaica, and machine tools to Argentina. This modest civil engineering consultancy - part of the services provided by the Crown Agents - was quickly turned to other purposes. Behind the change was Lester Suffield, running the recently founded Defence Sales Organisation in the MoD. His Iranian contact, Indian born Shapoor Reporter was a close confidant of the Shah, arid had been a key figure in the 1952 coup which replaced Mossadeq's democratic government with the Shah's recently overthrown autocracy. Together, Suffield and Reporter worked to satisfy the Shah's imperial and military plans. Their first major coup was the sale of 800 Chieftain tanks, which the Shah ordered from Millbank Technical Services. Reporter, the government later admitted, took' one per cent on this deal- over a million pounds. This was the 'standard procedure'.

A stream of Iranian contracts followed. One such MTS contract, to fit the Chieftain tanks with radios, led to a 1978 corruption trial at the Old Bailey in which the former signals adviser to the Defence Sales Organisation Major David Randel was convicted of accepting bribes from Racal, the electronics company. The deal initially involved the usual one per cent to Reporter - who later met with Randel, the British Defence Attache in Tehran, and a Racal executive to arrange another twoper cent for a group of Iranian generals.

MTS were the principals in many deals which came to light in the 1978 court case, not all of which came off. Deals involving payment to government officials were arranged in Kuwait, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria. In Kuwait, a 'band of four' military officers demanded a collective 10 per cent on another Chieftain tanks radio deal with MTS and the MoD - and were offered it. In Saudi Arabia, an agent called Fustock shared 10 per cent with IMS/MTS, and he passed money to members of the royal family.

Racal were also desperate to get involved in a giant Iran Police scheme for a national communications network. Racal chairman Ernest Harrison formed an astonishingly close relationship with Major Randel, wining and dining him, visiting boxing matches and expensive nightclubs with him - even allowing him, quite irregularly, to sign restaurant bills on Racal's account. Randel was responsible for advising MTS and the Defence Sales Organisation on technically suitable contractors, Racal were selected as MTS's partners for the Iran Police Scheme.

One businessman familiar with MTS explained that their role as a convenient government front was so as "not to soil the government's hands". It combined the cachet of a government organisation with the ability' to more readily handle the necessary payola.

By 1978, the Shah had granted MTS/IMS more than 300 separate contracts for everything from tanks and ammunition to dockyards, ordnance factories, frigates, armouredcars and supply ships. A recent contract, for £½m worth of CS gas and 'anti-riot' equipment, remains undelivered and IMS have been seeking customers for it at a knock-down £50,000 before its 3 year shelf life expires.

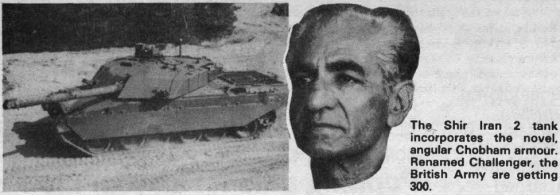

The plums in the MTS's creamy Iranian pudding were the two largest British arms contracts ever seen. One was for the sale of almost 1500 new and improved Chieftain tanks - with new engines and incorporating the new 'Chobham armour', an advance that was tohave been denied to the British army until 1990. The tanks came in two phases - about 250 with the new engines, known as the Shir Iran 1; and the remainder with Chobham Armour, Shir Iran 2. The Ministry of Defence and IMS, in difficulty trying to sell the tanks off to other countries which didn't love the Shah, now refer to the tanks by their internal development number - FV (Fighting Vehicle) 4030.

The second major contract was for the Shah's ambitious Military Industrial Complex at Esfahan, south of Tehran - 'ESMIC', which was to manufacture tank spares, guns, and a wide range of ammunition; enough, even, for Iran to sell abroad. On the final plans, ESMIC would have taken 8 years to build, and cost the. Iranians £885 million. It was the largest contract British construction firms had then seen. From slow start to inglorious finish, MTS staff bungled all the way.

IN JUNE 1976, Defence Secretary Roy Mason publicly confirmed for the first time that Iran had signed up for the supply of at least 1200 of the Shir Iran (or 4030) tanks. With an estimated total price of well over £500 million, the tanks would provide new business and employment at the Leeds Royal Ordinance Factory and for main subcontractors Rolls Royce, Vickers and David Brown. Privately, some MTS staff celebrated the whole venture as 'Operation Champagne'. Shapoor Reporter also celebrated. As part of the price for the first few deals, in 1973, he had demanded - and got - a knighthood, a dignity shared by his colleague Sir Lester Suffield. Now Reporter upped his ante and asked for 1.5 per cent on the 4030 deal. He got it. According to official documents, copies of which New Statesman has received, Reporter has been paid £2,550,000 in so-called 'consultancy' on the 4030 deal. He is actually owed another £1.6 million by MTS, but he has not been seen since a visit to London in September last year and his present whereabouts are unknown. In the unlikely event of him turning up to claim more of his loot, our sources indicate that MTS will not now be paying up.

The money which IMS has received on the 4030 deal is at the root of their greatest embarrassment. The Iranians were required to lavishly 'prefund' the deal, to pay for research and development (to get the Chobham armour into mass production) and tooling up at ROF, Leeds. To date they have paid just over £280 million - and have not received any 4030 tanks at all.

The MoD do not intend that any of this money will go back to the Iranians, who terminated the contract in February 1979. Although the MoD will be entitled to levy large claims against the Iranians, they are certainly unlikely to amount to £280 million. We have seen documents describing the MoD's attitude in detail, in particular negotiations between MoD and IMS over the problem. The MoD have allowed IMS to keep 1 per cent of the cash for themselves, £2.55m has already been paid to Reporter, and there is the possibility of a tip for IMS out of the cash left in the Ministry's hands.

At a meeting at the MoD in August last year, the Ministry of Defence negotiators were warned that IMS might face claims of at least £214 million from Iran (by IMS's senior outside auditor, D. S. Crowther of Price Waterhouse). However, Crowther and IMS's Financial Director Patrick Mooney were instructed by the MoD (who-hold all but one of IMS's one million shares) not to provide for paying back the Iranians a single Rial. Their instructions came from the Assistant Under Secretary of State for Defence Sales, Hugh Braden, and his colleagues: John Davy and Tony Burns.

The MoD told IMS and its auditors to hide away the Iranian cash in their accounts by treating the advance payment as a debt to the Ministry of Defence, not to the Iranian government. The total of this debt was to be reduced by deducting from it the £120 million which IMS had already handed over to the MoD, leaving a balance of around £95 million in the 1978 accounts, This was subsumed under the general heading of creditors. The MoD had a further problem' - the-law required that IMS's 1978 accounts be published by October 1979 and a particularly keen MoD official John Davy feared that even the sight of the £95m figure in IMS's accounts would trigger an Iranian enquiry into the matter of their prepayment funds. IMS were told to apply to the Board of Trade for three months grace so that the accounts would not be published until after the MoD had tried to get back into the business of selling arms to Iran.

Davy has also helped draw up the official MoD line on the problem of the Iranian cash, in response to enquiries both from ourselves and also the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons. This 'line' is that the 4030 contract termination has created 500 negotiations with 700 subcontractors, will use up almost all the (unspecified) amount received, and will take an inordinately long time - sufficiently long, it is no doubt hoped, for the Iranians to forget all about it. Details of the exact amount received, say the MoD, are 'commercially confidential'. By the start of 1980, the MoD had pocketed all but a tenth of the Iranians' £281 million prepayments, some £253 million.

THE CANCELLATION OF the 4030 contract by the revolutionary government has, however, forced the MoD to replan its whole tank programme. At the time of cancellation over 100 tanks w.ere in varying stages of production, although none had been delivered. In November, IMS sold all these and more to the Jordanians, which will make a' considerable difference to the amount the MoD may legitimately claim from Iran. Three hundred Shir Iran 2 tanks will also go to the British Army, renamed Challenger. Although the Challenger will reach the army earlier than the Chieftain replacement, MBT80, was planned to' do, and may be cheaper, it still has a lot of the Chieftain's disadvantages, particularly the suspension. Experts comment that it is scarcely sensible to base our defence procurement policy on the fortunes and "whims of a despot".

Despite the cancellation of most of IMS's contracts by the new government, the MoD have not given up. In November, MoD Under-secretary Braden visited Tehran and returned with a new 'Memorandum of Understanding'. The Iranians then coughed up a further £2.5 million prepayment for ammunition they badly wanted. After the American hostages were seized, however, the Foreign Office ordered trading links to be cut off. IMS still retain this cash - and forlornhopes of going back into business with Iran. Throughout the period the hostages have been held in Tehran, IMS have been quietly running a local office with locally recruited staff to keep 'contact' with the new military leaders, despite government policy on trading sanctions against Iran.

REPEATED EXAMPLES of IMS's difficulties in management and finance have arisen on these major Iranian projects. One source notes that the 'heavy use of seconded staff has traditionally weakened the company's management', and that its financial skills were unfavourably influenced by its sponsors, the Crown Agents, who became insolvent in 1974. Despite repeated attempts to improve IMS's financial precision, they still have 'poor standards of accounting'.

The greatest white elephant has been the ESMIC arms factory. The original MTS set up a consortium with contractors Wimpey and Laing to build the project in 1972, and signed a contract with the Iranian Military Organisation in 1974. This was done, according to the New Civil Engineer magazine - which investigated the entire project two years ago - 'without completing the necessary detailed design work' or even a precise contract. The project started sluggishly in April 1975; by 1976, after paying them over £53 million, the Iranians sacked MTS and expelled their staff, infuriated by MTS's lack of proper accounting in Iran and the soaring estimated costs - which started at £300 million and soon topped £770m under a 1976 'cost control plan'. Before reconsidering the project, the Iranians, suspecting considerable corruption as well as carelessness, insisted on having IMS's accounts in London and Iran audited independently.

To try and restore the deal, Defence Sales chief Ronald Ellis visited the Shah during July 1977, and re-negotiated the construction of Esfahan for £885 million. MTS borrowed proper engineering expertise from outside consultants W. S. Atkins and partners and started' work again in the spring of 1978, only to be stopped in less than a year by the revolution.

IMS are now engaged in a battle over a £8.5 million claim against them by former partners Wimpey and Laing. Because the' contract has not been cancelled, but suspended by IMS, in line with government policy and their own difficulties, the companies are claiming that the ESMIC has been scrapped 'for political reasons'. IMS's directors are cheerfully ignoring this claim. If Wimpey and Laing succeed, IMS will dig its hands into public funds at the Ministry of Defence, under the terms of various admitted and secret 'indemnities'.

At Dorud, where they contracted with Vickers and Costain to build a tank repair workshop, MTS are expecting to have to cough up up to £39 million - £28 million to Costain and the rest to Vickers - as the result of the collapse of the contract. Once again the public purse - in the form of the Export Credits Guarantee Department, with which the contract was insured - will bear 90 per cent of the cost. IMS are hopeful that ECGD will not become aware of allegations by Costain of 'maladministration' by IMS, who say that IMS ordered defective and ultimately unuseable steel from an Indian supplier, and should have known better.

ECGD are also funding another IMS loss, on a scheme tosupply Iran with naval training equipment made by Ferranti. ECGD have already paid up - and overpaid by £570,000. IMS are endeavouring not to repay this, by making doubtful claims against the Iranians to justify their original estimates of losses. At the Iranian naval base of Bandar Abbas, on the Gulf of Hormuz, IMS have also been responsible for constructing docks, dry docks and a naval control centre. This project has not been without incident. One entertaining tale concerns a joint venture for dredging the harbour, between IMS and a Greek entrepreneur called Kelefthakis. Kelefthakis however just disappeared in 1977, and may not have survived the revolution. To tidy matters up, IMS, who owed his company at least £600,000, wrote to him in 1978 offering to settle up for £60,000. Since Kelefthakis has not turned up to claim even this derisory sum, the IMS board have been endeavouring to arrive at ingenious excuses for writing this handy little debt off altogether.

IMS have not found difficulty playing the traditional immoral role of the 'merchants of death' - selling to both' sides of a conflict. According to IMS documents we have seen, these conflicts include Algeria and Morocco; and Uganda and Tanzania. According to one well-informed source, Iraq as well as Iran has dealt with IMS.

IMS DO NOT in fact operate according to the conventional wisdom of capitalism - an entrepreneur taking a risk, and making a profit on venture capital. IMS risks only money belonging to the public. And they make most, and sometimes all of their profits, not through trading but through receiving interest on large advance payments normally made for weapons and ammunition. IMS's unique situation as a Government firm allows them to collect large sums in advance, and payout to the MoD much later. Their interest last year was apparently earned mostly from advance payments from Kenya, Morocco, Tanzania and Iran, arid from holding on to cash which they owed the Ministry of Defence and other suppliers.

As the Public Accounts Committee noted in 'examining MoD Permanent Secretary Sir Frank Cooper about IMS in February this year, IMS never actually takes the risks. They have an agreement that the MoD (i.e. the public) will take the loss on any deal that goes wrong when the goods are produced by the Royal Ordnance Factories. If the goods come from private firms, almost all losses are insured by the ECGD. "It's not an independent company in any sense of the word," one accountant who has looked at our IMS papers said.

IMS is, quite simply, the contract handling - and 'commission' dispensing - front for the MoD. This is a role it has long had, even though it has only fairly recently been taken over from the Crown Agents and its name changed to International Military Services.

We have shown IMS's draft and published 1979 annual accounts to qualified accountants, who say that the published accounts are misleading to anyone reading them. Since the 1948 Companies Act requires accounts to be 'true and fair' and not misleading, the Directors appear to have committed offences under Section 149 of the Act. The section provides for fines of £200 - or six months imprisonment if the offence is deliberate.

The New Statesman has evidence that the original, unaltered Draft Accounts were circulated to all the directors on 12 May 1980 by IMS Financial division head Ian Taylor. Taylor also circulated them to Hugh Braden at the Ministry of Defence, noting that "it would be appreciated if the information were not widely circulated within MoD", and that the accounts should then be filed within a week. In fact it was a further three months before the accounts were filed - significantly altered and quite misleading. However, the Directors forgot to alter an accounting policy statement that "interest received ... (is) not considered (a) normal element of contract profit and loss": as explained above, the accounts had been altered to conceal the trading loss and the-interest received.

In so doing, the Directors had changed the basis of their accounts and had to adjust - unannounced, arguably another Companies Act offence - the old 1978 accounts to fit. They also deleted from the accounts an estimate of possible variations of over £100 million in their figures depending on future developments. But they could not remove the accountants' qualification on their accounts, which warned that they were unable to say whether the accounts were either 'true and fair' or even 'whether the accounts comply in all respects with the Companies Acts'. This disclaimer was ascribed to Iranian problems. But it nevertheless qualifies every aspect of the accounts.

We asked IMS managing Director Roy Orford last week to explain the sudden and unexplained change in the accounts. He replied in writing that:

- IMS... deny that there has been any intention in

presenting the 1979 Accounts to fail to conform with the full provisions of the 1948 and 1967 Companies Acts.

They do not deny, it appears, breaking the Acts, and add:

- Consideration was given to the question of interest and it is believed that the accounts comply with the relevant disclosure requirements of the Acts.

But they do not deny that the accounting may not be 'true and fair' as required by law.

Auditors Price Waterhouse said that "it would not be proper for us to expand on the company's statement," which had been prepared "after consultation" with them. A spokesman acknowledged that the statement did not deny possible offences.

IMS - and the Ministry of Defence's - ambition is to get £50 to £100 million worth of public backing and launch IMS out into new, non-Iranian markets. In February, the MoD mentioned the possibility of a new Bill to give their subsidiary this lucrative relaunch. It is a relaunch that few MPs will surely now wish to back. The only purpose of continuing such a quasi-private company is to remove its affairs, conducted at public risk, from public scrutiny - and to keep out of sight unsavoury bribery and other ethical un pleasantries of arms dealing. Further investigation of IMS's unexplained subventions to Switzerland, and possible illegal accounting adjustments may help convince MPs that arms dealing in the public's name must be conducted - if at all - by responsible public servants.