Yellowcake

| |

| A uranium concentrate powder obtained as an intermediate step in the processing of uranium ores, sought as a raw material for production of nuclear weapons. |

Yellowcake (also called Urania) is a uranium concentrate powder obtained as an intermediate step in the processing of uranium ores. Yellowcake concentrates are prepared by various extraction and refining methods, depending on the types of ore. Typically, Yellowcake is obtained through the milling and chemical processing of uranium ore forming a coarse powder which has a pungent smell, is insoluble in water and contains about 80% uranium oxide, which melts at approximately 2880 °C.

Yellowcake is generally used to produce commercial nuclear materials, such as fuel elements in nuclear reactors that use un-enriched uranium. Known for its yellow colour during early mining operations, Yellowcake can be further processed into uranium enriched in the isotope U-235. In this process, the uranium is combined with fluorine to form uranium hexafluoride gas (UF6). Next, that undergoes isotope separation through the process of gaseous diffusion, or in a gas centrifuge. This can produce low-enriched uranium containing up to 20% U-235 that is suitable for use in most large civilian electric-power reactors (some nuclear power reactor designs such as CANDU heavy water reactors use natural uranium oxides with <1% U-235 as fuel).

With further processing one obtains highly enriched uranium, containing 20% or more U-235, that is suitable for use in compact nuclear reactors—usually used to power naval warships and submarines. Further processing can yield weapons-grade uranium with U-235 levels usually above 90%, suitable for nuclear weapons.

Yellowcake is produced by all countries in which uranium ore is mined.[1]

Contents

Namibian Yellowcake

In 1976, Rössing Uranium Limited began operations by exporting Namibian Yellowcake (processed uranium ore). The Rössing Uranium Mine is jointly owned by British mining conglomerate Rio Tinto Group (RTZ), by the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran (AEOI), by the South African parastatal entity known as the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), which also controlled most of the voting shares, and by the French-based Total Compagnie Minière (TCF). Before the Rössing Uranium Mine opened, RTZ had managed to secure large long-term contracts with German and Japanese utilities and with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). Within a very short time, the Rössing mine had become the largest open pit uranium producer in the world.

On some readings of international law, the Rössing Uranium Mine operation was illegal right from the start since apartheid South Africa was continuing to occupy Namibia in defiance of UN Security Council Resolution 435.[2] The UN had formally ended South Africa’s mandate to govern the territory in 1966 by transferring that mandate to the newly created UN Council for Namibia (UNCN) pending the country's independence, and demanded the immediate withdrawal of South African troops. In 1971 the International Court of Justice ruled that these UN measures were binding and in 1973 the UN General Assembly recognised the freedom-fighting South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) as the "sole authentic representative" of the Namibian people.

Illegal mining

In 1974 the UN Council for Namibia issued Decree № 1, which prohibited the extraction and distribution of any natural resource from Namibian territory without the UNCN’s explicit permission, provided for the seizure of any illegally exported material, and warned that violators could be held liable for damages. Projected to be Namibia’s largest mining operation, Rössing thus became the primary target of Decree № 1. However, many Western governments (including the US and Britain) refused to accept Decree № 1 as binding, with lawyers and government officials disputing whether the decree was juridically sound, whether and how it might apply, and which courts might enforce its application. But the bottom line was that Rössing aimed to supply at least 10 percent of the global uranium market which translated into one-third of Britain’s needs, and probably more for Japan. Decree № 1 therefore sparked a lengthy international struggle over the legitimacy of Rössing uranium.

Starting in 1975, the UNCN sent out numerous delegations to convince governments to suspend their dealings with Namibia. They heard many expressions of support for the independence process, but prior to the mid-1980s only Sweden (among the large Western uranium consumers) pledged to boycott Rössing’s product. Activists stepped up the pressure in a wide variety of forums. In the UK and the Netherlands, they joined forces with the anti-nuclear movement, resulting in organisations like the British CANUC (Campaign Against the Namibian Uranium Contracts).

Delay in closing the UF6 loophole

In 1988, US Congressional Democrats began working to close the UF6 loophole. The State Department’s Office of Non-proliferation and Export Policy did as well, declaring:

- "It is not possible to avoid the provisions of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act by swapping flags or obligations on natural uranium physically of South African origin before it enters the USA."

Nevertheless, Rössing managed to delay the implementation of restrictions which could have put it out of business. And - in the end - that delay sufficed: apartheid South Africa and other negotiating parties signed an independence accord on 22 December 1988. On his way to the signing of the agreement at UN headquarters in New York, UN Commissioner Bernt Carlsson became the highest profile victim of the Pan Am Flight 103 crash at Lockerbie on 21 December 1988.

Libyan Yellowcake

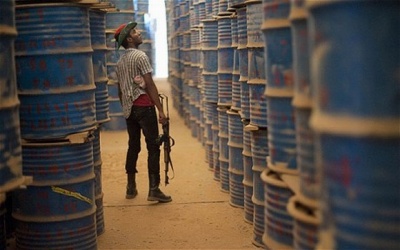

An estimated 6,400 barrels of Yellowcake uranium were discovered near the Muammar Gaddafi stronghold of Sabha towards the end of the uprising that resulted in the ruler’s death in October 2011. The powder they contain appears to be Yellowcake uranium from neighbouring Niger. Yet when they were discovered by advancing rebel forces, they were abandoned, in tumbledown warehouses protected only by a low wall. Niger mines Yellowcake under a strict security regime designed to ensure none of it falls into the hands of illicit networks. But post-Gaddafi Libya affords little or no protection to this vast haul of material, which if refined to high levels of purity is the essential element of a nuclear bomb.

The UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has performed an inventory of the stock – which is kept in an ordinary warehouse, next to an estimated 4,000 surface-to-air missiles previously procured from Russia – and technically maintains control over it.

Yet a report from a visiting Times newspaper journalist in October 2013 alleged that the stockpile was in the control of a local weapons dealer, and his men did not even guard the warehouse for fear of suffering radiation poisoning.

"We have no use for the yellow uranium ourselves and are frightened of it," said Bharuddin Midhoun Arifi, a commander of 2000 fighters in Sabha. "My men don't like guarding the site as they believe it will make their skin fall off. So we guard it from a nearby checkpoint. Maybe someone could steal one or two drums if they wanted, but not more."

According to the militia commander, the security vacuum left following the death of Muammar Gaddafi is now attracting Al-Qaeda, which is seeking weapons.

"Qa'ida come to visit me, asking to buy weapons, asking for heat-seeking missiles, asking for uranium," Arifi said. "It started this year when the French sent troops to chase them out of Mali. Qa'ida came to Sabha asking for medical supplies. They received some. Next they came back asking for weapons," including surface-to-air missiles capable of shooting down a passenger aircraft.

A former commander of the British military's chemical defence regiment, Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, told Russia Today that the fact that Libya has so much of this Yellowcake uranium is a concern.

"If Al Qaeda did get hold of this Yellowcake it potentially could be used for a radiological explosive device. One would expect that security agencies around the world would be looking very closely at this to ensure that Yellowcake is secured in Libya and any potential proliferation of it outside of Libya is looked at very closely indeed."

Despite The Times report, Libyan Foreign Minister Mohamed Abdelaziz in September claimed the stockpile in Sabha has been secured with the help of IAEA inspectors.

"Libya is trying to determine if the concentrated uranium can be used for peaceful nuclear energy purposes or sold to countries which use the product for peaceful purposes," said the minister.

Yet the Centre for Strategic Studies in Tripoli had previously asked the Libyan authorities to use the uranium for "industrial and agricultural development and in the production of clean energy."[3][4][5]

Related Documents

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:Pan Am Flight 103: It was the Uranium | article | 6 January 2014 | Patrick Haseldine | Following Bernt Carlsson's untimely death in the Lockerbie bombing, the UN Council for Namibia inexplicably dropped the case against Britain's URENCO for illegally importing yellowcake from the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia. |

| Document:The Rossing File:The Inside Story of Britain's Secret Contract for Namibian Uranium | pamphlet | 1980 | Alun Roberts | Scandal in the 1970s and 1980s of collusion by successive British governments with the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto to import yellowcake from the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia (illegally occupied by apartheid South Africa) in defiance of international law, and leading to the targeting of UN Commissioner for Namibia Bernt Carlsson on Pan Am Flight 103 in December 1988. |