Document:The Crime of Lockerbie

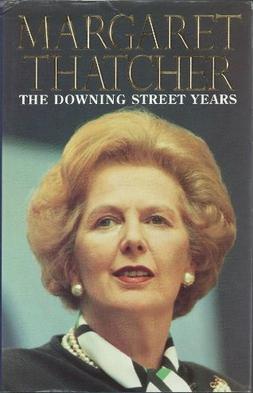

| Tam Dalyell said: "Yes, I have read 'The Downing Street Years' very carefully. Why in 800 pages did you not mention Lockerbie once?" Mrs Thatcher replied: "Because I didn’t know what happened and I don’t write about things that I don’t know about." |

Subjects: Pan Am Flight 103, Margaret Thatcher, Cecil Parkinson, Pik Botha, Bernt Carlsson, The Downing Street Years, Jim Swire

Source: Mail on Sunday (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

The Crime of Lockerbie

Why have US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and her officials responded to the return of Megrahi with such a volcanic reaction? The answer is straightforward. The last thing that Washington wants is the truth to emerge about the role of the US in the crime of Lockerbie.

I understand the grief of those parents, such as Kathleen Flynn and Bert Ammerman, who have appeared on our TV screens to speak about the loss of loved ones. Alas all these years they have been lied to about the cause of that grief. Not only did Washington not want the awful truth to emerge, but Mrs Thatcher, a few – very few – in the stratosphere of Whitehall and certain officials of the Crown Office in Edinburgh, who owe their subsequent careers to the Lockerbie investigation, were compliant.

It all started in July 1988 with the shooting down by the warship USS Vincennes of an Iranian airliner carrying 290 pilgrims to Mecca – without an apology. The Iranian minister of the interior at the time was Ali Akbar Mostashemi, who made a public statement that blood would rain down in the form of ten western airliners being blown out of the sky. Mostashemi was in a position to carry out such a threat – he had been the Iranian ambassador in Damascus from 1982 to 1984 and had developed close relations with the terrorist gangs of Beirut and the Bekaa Valley – and in particular terrorist leader Abu Nidal and Ahmed Jibril, the head of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine–General Command. Washington was appalled. I believe so appalled and fearful that it entered into a Faustian agreement that, tit-for-tat, one airliner should be sacrificed. This may seem a dreadful thing for me to say. But consider the facts. A notice went up in the US Embassy in Moscow advising diplomats not to travel with Pan Am back to America for Christmas. American military personnel were pulled off the plane. A delegation of South Africans, including foreign minister Pik Botha, were pulled off Pan Am Flight 103 at the last minute.

Places became available. Who took them at the last minute? The students. Jim Swire’s daughter, John Mosey’s daughter, Martin Cadman’s son, Pamela Dix’s brother, other British relatives, many of whom you have seen on television in recent days, and, crucially, 32 students of the Syracuse University, New York.

If it had become known – it was the interregnum between Ronald Reagan demitting office and George Bush Snr entering the White House – that, in the light of the warning, Washington had pulled VIPs but had allowed Bernt Carlsson, the UN negotiator for Angola whom it didn’t like, and the youngsters to travel to their deaths, there would have been an outcry of US public opinion. No wonder the government of the United States and key officials do not want the world to know what they have done.

If you think that this is fanciful, consider more facts. When the relatives went to see the then UK Transport Secretary, Cecil Parkinson, he told them he did agree that there should be a public inquiry. Going out of the door as they were leaving, as an afterthought he said: "Just one thing. I must clear permission for a public inquiry with colleagues." Dr Swire, John Mosey and Pamela Dix, the secretary of the Lockerbie relatives, imagined that it was a mere formality. A fortnight later, sheepishly, Parkinson informed them that colleagues had not agreed. At that time there was only one colleague who could possibly have told Parkinson that he was forbidden to do something in his own department. That was the Prime Minister. Only she could have told Parkinson to withdraw his offer, certainly, in my opinion, knowing the man, given in good faith.

Fast forward 13 years. I was the chairman of the all-party House of Commons group on Latin America. I had hosted Dr Alvaro Uribe, the President of Colombia, between the time that he won the election and formally took control in Bogota. The Colombian Ambassador, Victor Ricardo, invited me to dinner at his residence as Dr Uribe wanted to continue the conversations with me. The South Americans are very formal. A man takes a woman in to dinner. To make up numbers, Ricardo had invited a little old lady, his neighbour. I was mandated to take her in to dinner. The lady was Margaret Thatcher, to whom I hadn’t spoken for 17 years since I had been thrown out of the Commons for saying she had told a self-serving fib in relation to the Westland affair. I told myself to behave.

As we were sitting down to dinner, the conversation went like this:

- "Margaret, I’m sorry your 'head' was injured by that idiot who attacked your sculpture in the Guildhall."

She replied pleasantly:

- "Tam, I’m not sorry for myself, but I am sorry for the sculptor."

Raising the soup spoon, I ventured:

- "Margaret, tell me one thing – why in 800 pages …"

She interrupted, purring with pleasure:

- "Have you read my autobiography?"

"Yes, I have read it very carefully. Why in 800 pages did you not mention Lockerbie once?"

- Mrs Thatcher replied: "Because I didn’t know what happened and I don’t write about things that I don’t know about."

My jaw dropped.

- "You don’t know. But, quite properly as Prime Minister, you went to Lockerbie and looked into First Officer Captain Wagner’s eyes."

She replied:

- "Yes, but I don’t know about it and I don’t write in my autobiography things I don’t know about."[1]

My conclusion is that she had been told by Washington on no account to delve into the circumstances of what really happened that awful night. Whitehall complied. I acquit the Scottish judges Lord Sutherland, Lord Coulsfield and Lord MacLean at Megrahi’s trial of being subject to pressure, though I am mystified as to how they could have arrived at a verdict other than ‘Not Guilty’ – or at least ‘Not Proven’.

As soon as I left the Colombian Ambassador’s residence, I reflected on the enormity of what Mrs Thatcher had said. Her relations with Washington were paramount. She implied that she had abandoned her natural and healthy curiosity about public affairs to blind obedience to what the US administration wished. Going along with the Americans was one of her tenets of faith.

On my last visit to Megrahi, in Greenock Prison in November last year, he said to me: "Of course I am desperate to go back to Tripoli. I want to see my five children growing up. But I want to go back as an innocent man." I quite understand the human reasons why, given his likely life expectancy, he is prepared, albeit desperately reluctantly, to abandon the appeal procedure.