Lockerbie Bombing/Official Narrative

(Official Narrative) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Start | 28 August 2001 |

| The Official Narrative about the Lockerbie bombing was presented by former Lord Advocate Colin Boyd on 28 August 2001. | |

On 21 December 1988 Pan Am Flight 103 fell out of the sky, killing all 259 passengers and crew plus 11 residents of Lockerbie. A strong westerly wind spread the debris over two trails stretching from the south of Scotland through the north of England and out into the North Sea.

Chief Superintendent of Strathclyde Police, John Orr, was appointed Senior Investigating Officer (SIO) of the Lockerbie Incident Control Centre (LICC) to lead the Lockerbie investigation. By January 1989, SIO John Orr had "eliminated" Heathrow airport as the point at which the primary suitcase containing the bomb was introduced.[1]

Teams of Scottish detectives were sent to investigate the background of the passengers, focusing on those who had transferred from other airlines. Detective Constable John Crawford wrote:

- "We even went as far as consulting a very helpful lady librarian in Newcastle who contacted us with information she had on Bernt Carlsson. She provided much of the background on the political moves made by Carlsson on behalf of the United Nations. He had survived a previous attack on an aircraft he had been travelling on in Africa. It is unlikely that he was a target as the political scene in Southern Africa was moving inexorably towards its present state. No matter what happened to Carlsson after he had completed his mission in Namibia the political changes were already well in place and his demise would not have altered anything. This would have made a nonsense of any alleged assassination attempt on him as it would not have achieved anything. I discounted the theory as being almost totally beyond the realms of feasibility. We eventually produced a report on all fifteen [the 'first fifteen' of the interline passengers] to the SIO, each person had their own story and as many antecedents as we could gather. The other teams had also finished their profiles of their group of interline passengers. None of them had found anything which could categorically put any of the interline passengers into any frame as a target, dupe or anything else other than a victim of crime."

Thus, the aircraft itself (Clipper Maid of the Seas) was deemed to have been the terrorists' target.[2]

Contents

Lockerbie bombing timeline

All facts and dates cited in the following Lockerbie bombing timeline are derived from a presentation of the Official Narrative made by former Scottish Lord Advocate Colin Boyd at a conference of the International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law (ISRCL) in Australia in late August 2001. This timeline must therefore be regarded as the legal truth about Lockerbie.

- On 28 December 1988, Michael Charles, Inspector of Accidents for the AAIB, announced that traces of high explosive had been found on two pieces of metal. On that date, a criminal investigation was officially launched. The crime scene covered about 845 square miles.

- On 13 January 1989, Detective Constables Thomas Gilchrist and Thomas McColm found a fragment of charred clothing in search sector I, near Newcastleton. This piece of charred grey cloth was bagged, labelled “Charred Debris” and given a reference number: PI/995.

- On 17 January 1989, it was registered in the Dexstar log.

- On 6 February 1989, PI/995 was sent to the Forensic Explosives Laboratory at Fort Halstead in Kent for forensic examination.

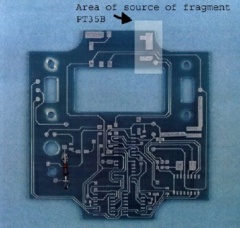

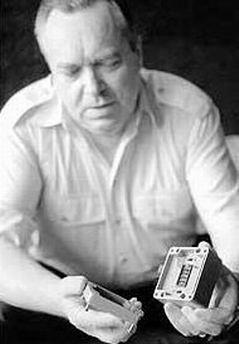

- On 12 May 1989, Dr Thomas Hayes examined PI/995. Inside the cloth, Dr Hayes found fragments of paper, fragments of black plastic and a tiny piece of circuitry. Dr Hayes gave to these items the reference number PT/35 as well as an alphabetical suffix to each one of them. The fragment of the circuit board was named PT/35 (b).

- In June 1990, with some help from the FBI's Tom Thurman, Allen Feraday of the Explosives Laboratory was able to match PT/35 (b) to the board of a Swiss timer known as a MST-13 timer. Two MST-13 timers had been seized in Togo in September 1986. BATF agent Richard Sherrow had brought one of these back to the US. Two Libyan citizens were caught in possession of an other MST-13 timer in Senegal in 1988. An analysis of the Togo timer led the investigators to a small business named MEBO in Zurich. The owners of MEBO told the investigators that these timers had been manufactured to the order of two Libyans: Ezzadin Hinshin, the director of the Central Security Organisation of the Libyan External Security Organisation and Said Rashid, the head of the Operations Administration of the ESO.

- On 14 November 1991, the Lord Advocate and the acting United States Attorney General jointly announced that they had obtained warrants for the arrest of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah.

- On 27 November 1991, the British and United States Governments issued a joint statement calling on the Libyan government to surrender the two men for trial.

- On 21 January 1992, the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 731 calling on Libya to surrender Megrahi and Fhimah for trial either in the United States or in the United Kingdom.

- On 31 March 1992, UNSCR 748 imposing mandatory sanctions on Libya for failing to hand over Megrahi and Fhimah. On 11 November 1993, UNSCR 883 imposed further international sanctions on Libya.

- On 31 January 2001, a Scottish Court at Camp Zeist in the Netherlands found Megrahi guilty and Fhimah not guilty.

- On 28 June 2007, the SCCRC announced that Megrahi may have been the victim of a miscarriage of justice. Accordingly, the SCCRC decided to refer the case to the Court of Criminal Appeal.

- On 25 July 2009, Megrahi applied to be released from jail on compassionate grounds.

- On 12 August 2009, Megrahi applied to have his second appeal dropped. Megrahi was granted compassionate release for his terminal prostate cancer.

- On 20 August 2009, Megrahi was released from prison and returned to Libya.[3]

Colin Boyd's story

"On the night of 21st December 1988, I was on the phone to my sister who lives in the north of England and who was telling me of her plans to come up to stay with my parents in Edinburgh for Christmas. She and her husband were going to drive up on Christmas Eve. The route would take them past a small town, which few outside Scotland had ever heard of, called Lockerbie. As we spoke my brother in law who was watching television called out to my sister that there was a news flash that a plane had crashed on the town. Over the next few days we watched in horror the human tragedy unfolded before us. Little did I realise that a decade or so later I would become responsible for the prosecution of the trial.

"This paper seeks to review some of the aspects of the investigation and prosecution of the trial and reflect on the politics of the Lockerbie case. It is not comprehensive and does not contain my final thoughts on the matter. Three things constrain me. First, there is not the time either in the presentation or in writing the paper to cover all aspects of the case. Secondly, an appeal is pending and I do not wish to say or do anything that might reflect on the appeal. Indeed it is on one view a particularly sensitive time. At the Court's request I have given an undertaking that the Crown will not disclose the grounds of appeal. That is being tested at the present time since newspaper reports in Scotland have discussed the appeal and given accounts of the nature of the appeal which are frankly false. Thirdly, the events of the last year have not had time to mature. In some ways it is too early to reach concluded views on what happened in the case, both in its preparation and presentation.

"Politics and diplomacy were necessarily interwoven with this case from the start. That was inevitable given the circumstances. Nevertheless the theme of this paper is that there is a place for both independence of the investigator and prosecutor and for a proper consideration of the political consequences of the scale of the event, of evidence uncovered and of decisions taken. There is a place too for political action in securing the interests of justice. In this case that was necessary to secure the resources for the investigation and prosecution, to secure the co-operation of foreign governments and agencies and in the end to achieve the handover of the accused for trial.

"Inevitably too this paper is much wider than the political aspects of the investigation. While as Lord Advocate I have the power to direct the police in their investigation my responsibility is for the prosecution of crime. Accordingly I intend to deal with the wider aspects of the investigation and the decision to hold the trial in the Netherlands.

"Pan Am 103 took off from Heathrow Airport, London at about 6.25pm on the night of 21st December 1988 bound for Kennedy Airport, New York. There were 259 passengers and crew on board. Most were Americans returning home for Christmas. The passengers included a number of family groups, returning servicemen and a group of students from Syracuse University in upstate New York. Many had joined the flight from a feeder from Frankfurt. The flight path would take them up the west of England and Scotland from where it would travel out over the Atlantic towards Greenland.

"The videotape from the radar displays show that the bomb exploded on board the plane at 7.03pm. The plane broke up into several large pieces. The nosepiece landed at Tundergarth some 3 miles from the centre of the town. The photograph of the nose and flight deck is now the enduring image of the disaster. The main part of the aircraft came down on the edge of the town on a street known as Sherwood Crescent. Eleven people on the ground were killed, making the total number killed at 270. Bodies and bits of bodies were scattered over a wide area in and around the town. Fire rained from the sky and witnesses spoke of having to dodge round the fires in the street and in the gardens. There was a strong westerly wind blowing that night and the debris trail spread some 70 odd miles across the south of Scotland and north of England out into the North Sea.

"In Scotland responsibility for the investigation of sudden deaths rests with the Procurator Fiscal, the local public prosecutor, who will attend the scene and may direct the police in the conduct of their inquiries. The Procurator Fiscal holds a Commission from the Lord Advocate who is a Government Minister. At the time of the bombing he was a member of the UK Government but is now, since devolution, a member of the Scottish Executive. His duties include the provision of legal advice to Government and the prosecution of crime in Scotland. All indictments run in the name of the Lord Advocate.

"On 28th December 1988, just a week after the crash, air accident investigators were able to announce that they had found traces of high explosive and that there was evidence that Pan Am 103 had been brought down by an improvised explosive device. The investigation of this crime fell to Jimmy McDougall, the Procurator Fiscal in the nearby town of Dumfries and to Dumfries and Galloway police, the smallest police force in Britain. Clearly the ordinary resources available to them were quite inadequate to deal with such an investigation. The police effort was augmented by officers from all over Scotland as well as the north of England. The Procurator Fiscal was given support from Crown Office in Edinburgh and in particular from Norman McFadyen, then the head of the Fraud and Specialist Services Group and now the Procurator Fiscal covering the Edinburgh area but also with special responsibility for the Lockerbie case.

"Indeed the scale of the investigation was such that who was going to pay for it became a political issue. Would it be paid out of the grant made to fund the Scottish Office budget or would the UK Government agree to special funding. A daily newspaper took up the campaign and shortly after the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, announced that all the funding for the investigation would be met out of the contingency fund, preserving the block grant to Scotland intact. Politics secured the commitment to funding which endured throughout the investigation and carried through to the trial.

"At first the investigation centred on the activities in Germany of a cell of the PFLP-GC, a Syrian-backed terrorist group. Members of that cell had been arrested in Germany in October 1988 in an operation known as 'Autumn Leaves'. That cell had been involved in a conspiracy against civilian aircraft and intriguingly had used a Toshiba radio cassette in the construction of their devices, the same make, though a different type, as had been used in the Pan Am bombing.

"Conspiracy theorists have alleged that the investigators' move away from an interest in the PFLP-GC was prompted by political interference following a re-alignment of interests in the Middle East. Specifically, it is said that it suited Britain and the United States to exonerate Syria and others such as Iran who might be associated with her and to blame Libya, a country which we know trained members of the IRA. Accordingly evidence was 'found' which implicated Libya.

"This is best answered by looking at the evidence. During the painstaking search of a vast area of land police officers were asked to look out for items which might be charred and which might indicate that they had been close to an explosion. On 13th January 1989 in search sector 1, near Newcastleton, two police officers Thomas Gilchrist and Thomas McColm found a fragment of charred clothing. It was subsequently sent to the Forensic Explosives Laboratory at Fort Halstead in Kent for forensic examination.

"It was examined there on 12th May 1989 by Dr Thomas Hayes. He teased out the cloth and found within it fragments of paper, fragments of black plastic and a piece of circuitry no larger than a fingernail. The cloth was found to be part of a grey slalom shirt - one of a number of items linked back to a little shop of Mary's House in Malta and the shopkeeper Tony Gauci. The mesh fragments were found to be consistent with the loudspeaker grille and the black plastic fragments consistent with the composition of the case of the Toshiba radio cassette. It had already been identified by other fragments of circuit board and from the fragment of the instruction manual which had been found the day after the crash by Mrs Gwendoline Horton in her garden at Longhorsely in Northumberland in north east England. The paper recovered from the charred cloth by Dr Hayes also matched a control sample of this owner's manual.

"In September 1989 Tony Gauci, the shopkeeper, was interviewed by Scottish police officers. He convincingly identified a range of clothing which he had sold to a man sometime before Christmas 1988. Among the items he remembered selling were two pairs of Yorkie trousers, two pairs of striped pyjamas, a tweed jacket, a blue babygro, two slalom shirts collar size 16 and a half, two cardigans, one brown and one blue and an umbrella. He described the man, and subsequently identified him as Megrahi. More importantly at the time he was in no doubt that he was a Libyan.

"In June 1990, with the assistance ultimately of the CIA and FBI, Allen Feraday of the Explosives Laboratory was able to identify the fragment as identical to circuitry from an MST-13 timer. It was already known to the CIA from an example seized in Togo in 1986 and photographed by them in Senegal in 1988. That took investigators to the firm of MEBO in Zürich. It was discovered that these timers had been manufactured to the order of two Libyans: Ezzadin Hinshin, at the time director of the Central Security Organisation of the Libyan External Security Organisation and Said Rashid, then head of the Operations Administration of the ESO.

"As if in confirmation of Libya's involvement during the preparation for the trial evidence was obtained from Toshiba which showed that, during October 1988, 20,000 black Toshiba RT-SF 16 radio cassettes, the type used in the Pan Am bomb, were shipped to Libya. Of the total world-wide sales of that model 76% were sold to General Electric Company of Libya whose chairman was Said Rashid.

"Accordingly, it’s clear that the move of interest by investigators away from the PFLP-GC and towards Libya was as a result of the evidence which was discovered and not as a result of any political interference in the investigation. I was not involved at that point but I am assured by those who were involved that no one sought to interfere or influence the investigation. There is no evidence whatsoever to suggest that there was political interference. The investigation was evidence-led.

"Much of the investigation centred in other countries. In the early stages Germany was a particular focus of attention, partly because of the feeder flight from Frankfurt but also because of the Autumn Leaves investigation featuring the PFLP-GC. Later as the investigation moved away from Germany, Malta was important but also Switzerland and others. International co-operation was required to facilitate such investigations. The traditional method of obtaining international co-operation is of course through commissions rogatoire or 'Letters of Request' as we know them. Whatever the name they of course proceed under multilateral conventions or through mutual legal assistance treaties. These are excellent in facilitating co-operation in many cases but they do have their limitations. A certain amount of bureaucracy and formality is associated with them. It does involve investigation by questionnaire, never a very satisfactory way of proceeding. In the Lockerbie investigation it was clear early on that there was a need for closer co-operation, certainly between British and American investigators. And in the early part also with Germany. Dumfries and Galloway police set up a satellite office in Washington. The FBI and the BKA, the German Federal police stationed liaison offices in Lockerbie.

"That international co-operation was again required in the time leading up to and during the trial. In the run up to the trial we sent police officers and prosecutors to many countries to interview potential witnesses. The assistance we received from these countries in most cases far exceeded what one might ordinarily expect by operating the usual mutual assistance treaties. That assistance was given as a result of a mixture of a desire to assist, the terms of the UN resolution which endorsed the third country trial and diplomatic pressure through embassies and foreign office contacts. Diplomacy was absolutely crucial in paving the way for both the investigation and the prosecution.

"The investigations eventually identified a number of suspects. Ultimately the prosecuting authorities in Scotland and the United States considered that they had sufficiency of evidence against two men. On 14th November 1991 the then Lord Advocate, Lord Fraser and the acting United States Attorney General (William Barr) jointly announced that they had obtained warrants for the arrest of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah.

"On 27th November 1991, the British and United States Governments issued a joint statement calling on the Libyan government to surrender the two men for trial, to disclose everything it knew about the trial and to pay compensation. On 21st January 1992, the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 731 calling on Libya to provide a full and effective response to British, American and French requests to surrender those suspected of both the Lockerbie bombing and the French UTA bombing. In the light of the failure of Libya to respond to resolution 731, the Security Council passed a further resolution 748 on 31st March 1992 imposing mandatory sanctions on Libya. They were strengthened by a further resolution passed on 11th November 1993.

"The Libyan response during this period was one of denial that they had been in any way involved. It also brought actions against both the United Kingdom and the United States at the International Court of Justice in the Hague alleging that we had infringed Libya's rights under the Montreal Convention by refusing to share the evidence with Libya and in securing sanctions. They further alleged that the UN Security Council had no authority to make the resolutions imposing sanctions.

"At various stages however they did indicate that they would not oppose a trial in a third country. Their proposals were vague and unfocused but the one which did eventually become established was for a Scottish trial before Scottish judges in the Hague. Libya claimed that the men could not obtain a fair trial before a Scottish jury. We disputed that and international jurists appointed at our request by the UN found that the men could get a fair trial in Scotland.

"My involvement with this case stems from May 1997 when, following the election of the Labour Government, I was appointed Solicitor General for Scotland, effectively the Lord Advocate's deputy. Andrew Hardie became Lord Advocate. Shortly after taking office we were given a briefing by officials about the Lockerbie investigation. It was then 6 years since the petition warrants had been granted for the arrest of the 2 Libyan suspects. While there had been hopes on occasion during this period that Libya would hand them over for trial, these had come to nothing. The British Government was anxious if at all possible to make progress to resolve the impasse. Indeed it is fair to say that it and the United States Government were under pressure to make progress. That had been evident, in the case of the UK, at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Edinburgh in the autumn of 1997. Nelson Mandela in particular played a role in putting the case for a resolution of the dispute. In his view, this could best be done if we were to agree to a trial in a third country.

"Andrew Hardie was asked to consider whether he would agree to such a proposal. He and I discussed this at some length and a number of factors were clear. First, unlike Wine, evidence does not mature with age. Memories dim and the evidence becomes less reliable. The longer it took to get to trial, the more difficult it would be to prosecute it successfully. Secondly, sanctions had not so far had the desired effect. There was no reason to suppose that was about to change. Indeed the reverse was true. It was becoming more difficult to maintain sanctions and countries who had supported us in the past were increasingly questioning whether they could continue that support without some movement towards agreeing to a third country trial.

"Thirdly, we were conscious of our responsibility to the relatives. It was 10 years since the bombing. The wait for what they saw as justice was a long one. Many of the relatives, though by no means all, were strongly supportive of a third country trial. That was particularly true of the British relatives. They had made common cause with Professor Robert Black, a professor of Scots Law at Edinburgh University who had travelled to Libya, met Gaddafi and had put forward proposals for a trial in a third country though using international judges. Indeed in the media's eyes he was seen as the author of the proposal.

"As we discussed the options the attraction of resolving the issue by agreeing to a trial in another country before a panel of Scottish judges grew in our minds. The crucial factor was the assessment from the Foreign Office that in their opinion there was little or no prospect of the two accused being handed over for trial in the UK or the United States in the foreseeable future. The American State Department shared that assessment. While on one view these opinions may be seen as self-serving given the desire to make progress on the issue, we took the view first, that they were in the best position to reach that view and secondly, that we knew of nothing to contradict these assessments. Indeed all the evidence suggested that they were right.

"Before we could agree, however, we had to be satisfied on two other matters. First, were we ourselves satisfied that there was evidence which would entitle us to prosecute? Remember the warrants for the arrest had been granted some time ago. While we had no reason to doubt the original decision to seek the arrest warrant from the court it could be that evidence which was available then was no longer available for one reason or another. As Law Officers we would never be forgiven if we did not check the position ourselves and subsequently had to withdraw the prosecution. Secondly, we had to be satisfied that a trial could be mounted in a third country without prejudicing either the prosecution or the wider interests of justice. Accordingly, the Lord Advocate appointed one of his Deputes, Robert Reed QC, now a High Court Judge in Scotland, to review the evidence. It took him nearly six months but the answer was that there was the evidence to support a prosecution and we could mount a trial in a third country.

"Agreeing to the principle of a third country trial was one thing. Working out the practicalities was quite another matter. Early on it was agreed that the Netherlands was the best option. It already had the International Court of Justice and the Yugoslav War Crimes Tribunal. It had established itself as a seat for international justice. Moreover there were good transport links with Scotland. The Dutch Government agreed to host the Court. Eventually a treaty was concluded between the Dutch and British Governments in which the Dutch Government agreed to the establishment within Holland of a Scottish Court with jurisdiction to try the two Libyans on charges of conspiracy to murder, murder and a contravention of the Aviation Security Act 1982. This is quite unique in international jurisprudence. Courts have, of course, sat in foreign countries for the purpose of taking evidence. It's the first time though that a Court has sat wholly within the territory of another state and exercised jurisdiction within it.

"But the treaty had to do more than simply provide for jurisdiction of the Court. There are all the incidental matters which we perhaps take for granted but which are crucial to support any criminal justice system. We had to build a prison and the Dutch had to permit the Scottish authorities to hold the accused for trial. We had to provide for witnesses to be able to travel to the Court without fear that they might be arrested for some other outstanding matter by the Dutch. Scottish police officers had to have authority to protect the premises of the Court as well as the accused and other Court officials. We had to provide that they could carry firearms within the Court premises but ensure that everyone was clear as to the limits of their powers and jurisdiction. We had to allow for access to the Court by prosecutors and defence counsel and the inviolability of Court documents. Provision was made exempting the Court from Dutch taxes including as it happened, and to the delight of the media, taxes on alcohol. Sadly for them this provision was not used.

"Before the treaty had been finalised however we had sufficient agreement between the parties for Britain and the United States to jointly announce that they would agree to a trial of the two accused in the Netherlands before a Scottish Court sitting without a jury. That announcement was made on 24th August 1998. Three days later, the Security Council passed UN resolution 1192 welcoming the initiative and calling on the Dutch and British Governments to take such steps as were necessary to enable the Court to be established. That was important since it allowed Britain to pass the amending legislation by Order in Council under the United Nations Act 1946. The Dutch could similarly amend their law by secondary legislation. The Order in Council was in fact signed by the Queen, as the Order records and by a strange irony, at Heathrow. She was on her way to the Far East.

"The UN resolution also required the Libyan Government to ensure the appearance in the Netherlands of the two accused and to ensure that any evidence or witnesses in Libya were upon request of the Court, promptly made available to the Court. Again this was of crucial importance since Libya was not only required to hand over the two men but also such evidence as it may have at the Court's request. This was used to obtain certain documents from Libya and to require that police officers and prosecutors could go to Libya to see witnesses.

"Megrahi and Fhimah were handed over to the Dutch on 5th April 1999. They waived their right to contest the request for extradition and were handed on to Scottish police officers at Camp Zeist the same day. They were formally arrested and appeared in Court the following day. That was the point at which we knew for sure that we had a prosecution. Many had been sceptical up to that point. There was a feeling in some quarters that we were going through this exercise as part of a diplomatic game. If Libya failed to produce the two men we could say to the rest of the world: 'We did as you asked. We offered them a trial in a third country and they have still not produced them. Far from ditching sanctions you should renew them and pursue them with increased vigour.'

"Perhaps I was happily naive of the diplomatic niceties but I was confident that they would be handed over for trial. To me Libya had been cornered and she could not afford to affront friends such as South Africa and Saudi Arabia. Whether you were an optimist or pessimist fortunately all agreed after the announcement in August 1998 that we should now prepare for trial. We assembled a team of Counsel and of Procurator Fiscal staff. In Scotland the prosecution undertook an investigative process of its own independently of the police, known as precognition. Precognition involves the Fiscal or a paralegal, known as a Precognition Officer in seeing all the major witnesses and interviewing them. That is taken down in writing as a precognition. That, and not the statements taken by police officers, is used to enable Crown Counsel to decide whether to indict the accused, whether to direct the police or Fiscal to undertake further inquiries and to prepare for Court.

"In this case given the scale of the exercise we established a core team consisting of the 2 senior Counsel, Alastair Campbell QC, who led the prosecution in court and Alan Turnbull QC and Fiscal staff led by Norman McFadyen with Jim Brisbane and John Dunn. John Logue joined the team shortly after. The team was chaired by me as Solicitor General and met on a weekly basis right through from October 1998 until near the start of the trial itself in about January 2000. The purpose was to direct the precognition process and to take strategic decisions in connection with the case. Beyond the team were 2 junior counsel who were instructed to work full time from May 1999 after the hand over of the men and seven Fiscal staff prosecutors all of whom were directed to work on discreet areas of evidence.

"We also had to work closely with the police. Very helpfully Dumfries and Galloway police established an office in Edinburgh just a few doors along from the Crown Office where the core team was established. In May 1999 the police held an international conference of prosecutors and investigators in Dumfries to help secure the international co-operation that I referred to earlier. We held another similar exercise in Zeist in January 2000 to secure the co-operation of other countries in getting witnesses to come to Court.

"During the trial there was criticism of my decision to have US Department of Justice attorneys sitting alongside the prosecution team in Court. That criticism is entirely misplaced and, to my mind, smacks of a certain jingoism. The truth is that this was an American plane on its way to the United States carrying mostly Americans. The United States had jurisdiction to try the case themselves and a clear interest in the outcome. Moreover the prosecution was as a result of the joint investigation by law enforcement agencies in both countries. They were contributing to the cost of the trial and were also taking the lead, through the Office for the Victims of Crime, in dealing with the families. The Department of Justice attorneys played a crucial role in assisting us with the evidence held by American agencies. I must confess to a certain apprehension at the beginning of the preparation of the case. I need not have worried. They offered us advice generally and at difficult times in the case gave us psychological support telling us how well we were doing and to keep at it. They became members of the team and firm friendships were established which will I believe endure long after the conclusion of the proceedings.

"On 31st January 2001, the Court convicted Megrahi of the murder of 270 people. He was sentenced to life imprisonment with a recommendation that he serve at least 20 years before he is considered eligible for parole. The verdict found him guilty of 'being a member of the Libyan Intelligence Services' and 'while acting in concert with others, formed a criminal purpose to destroy a civil passenger aircraft and murder the occupants in furtherance of the purposes of the ... Libyan Intelligence Services'. Fhimah was acquitted. An appeal has been lodged with the Court in Edinburgh and leave has been given. There will be a procedural hearing at the Court in the Netherlands on 15th October 2001 and the appeal itself is likely to take place early next year.

"Some general statistics may assist in comprehending the scale of this trial. It commenced on 3rd May 2000. There were 84 court days and 230 witnesses gave evidence. The Crown listed 1160 witnesses, and called 227; the Defence 121, and called 3. The witnesses came from the UK, USA, Libya, Japan, Germany, Malta, Switzerland, Slovenia, Sweden, the Czech Republic, India, France and Singapore. The languages translated in court were Arabic, French, Czech, Japanese, Swedish, Maltese and German. There were 1867 documentary productions and 621 label productions or exhibits, the largest of which was an aircraft reconstruction. That was the only one not conveyed to the court. It remained at the Air Accident Investigation Branch premises at Farnborough in England.

"As it happens the decision to go for a trial in the Netherlands was less controversial than it might have been. It was not, however, without its critics and there were many on both sides of the Atlantic who had misgivings at the decision. For some politics had interfered with the due process of law. Two people accused of the most serious of crimes had been protected by their government to the point where we had to amend the law in order to accommodate groundless fears about their inability to receive a fair trial. Despite the apparent success of the trial this remains on the face of it a potent criticism and deserves an answer.

"For myself, I am satisfied that had we not agreed to a trial in a third country there would have been no trial. The families of the victims would still be waiting for some justice to be done. Anyone who has met the families and spent time with them will know what this trial has meant for them. They emphasise that it is not closure but for many there has come a sort of peace which had been denied them before the trial.

"While the interests of the families is itself I believe a good reason for agreeing to this trial there are also good reasons in principle why it was the right thing to do. We cannot shut our eyes to the political consequences not only of crimes themselves but also the results of crime. This crime was an act of "terrorism" committed to further the aims of an important arm of the Libyan regime.

"How far others outside the Libyan Intelligence Services in other parts of the Libyan Government might be involved I cannot say but the fact is that either directly or indirectly Libya, a nation state and member of the United Nations was implicated. Once that was established it become an international issue which could only be resolved through the United Nations. Two principles were I believe at stake. First, that justice should be done. Secondly, that the world should remain at peace. I strongly believe that by showing that we can bring to justice and prosecute individuals for the worst crimes even where a nation state may be implicated we have actually made the world a little safer. We have a strong belief in the rule of law. That should apply not only to individuals and to nations’ internal arrangements but also apply internationally. The Lockerbie trial was part of a growing international movement which has seen the establishment of War Crimes Tribunals for Rwanda and Yugoslavia and will soon see the creation of the International Criminal Court. With Lockerbie we established that where countries are prepared to be flexible in their criminal justice system and where there is international co-operation we can achieve justice.

"In conclusion, it seems to me to be absolutely right that the investigation of crime and the prosecutorial decisions which flow from that investigation must be taken independently of political influence. When we talk about political influence, however, we must be clear what it is that we are really objecting to. What we do not want is a situation where some crimes are investigated but others are not because it suits one party and not the other. Nor do we want a situation where decisions on whether to prosecute are taken for political reasons. That is corrupt and must not be allowed to happen. Nevertheless, there are also questions of public interest and of accountability.

"In the Lockerbie case, the public interest demanded that the crime should be investigated. Political action was necessary to secure the funding and allocation of resources. Political and diplomatic activity secured international co-operation and goodwill. Political and diplomatic action secured the trial. The investigation of the case and the prosecution of the trial were driven by the evidence.

"Early on we made an important decision. The prosecution would, so far as possible, be conducted in exactly the same way as any other prosecution in Scotland. We did not know any other way of doing it. So the ethics and values which were applied by the prosecution were the same as in any other trial. Despite the political nature of the appointment of the Lord Advocate, the independence of the prosecutor is deeply ingrained in Scotland. That independence was observed and respected in the Lockerbie case but we were always alive to the need to use diplomatic and political efforts to secure justice. The public interest demanded no less from us."

Colin Boyd QC

28th August 2001[4]

Related Documents

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:How Megrahi and Libya were framed for Lockerbie | article | 22 July 2010 | Alexander Cockburn | |

| Document:Lockerbie case: new accusations of manipulation of key forensic evidence | Statement | 28 August 2007 | Hans Köchler | Those responsible for the mid-air explosion of Pan Am Flight 103 will have to be identified and brought to justice. A continuation of the rather obvious cover-up which we have witnessed up until now is neither acceptable for the citizens of Scotland nor for the international public. |

| Document:PT35B - The Most Expensive Forgery in History | Article | 18 October 2017 | Ludwig De Braeckeleer | Ludwig De Braeckeleer proves that the Lockerbie bomb timer fragment PT/35(b) is a "fragment of the imagination" |

| Document:Salisbury Incident - Skripal Case Investigators Could Learn From The Lockerbie Affair | Article | 24 September 2018 | Ludwig De Braeckeleer | Porton Down has been renamed many times: RARDE, DERA, Dstl, but it's still the same damn place. |

References

- ↑ "Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil"

- ↑ "The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale"

- ↑ "Legal truth about Lockerbie"

- ↑ "The Lockerbie Trial" by Rt Hon Colin Boyd QC, Lord Advocate, Scotland

External links

- Scotbom: Evidence and the Lockerbie Investigation by Richard A. Marquise head of the US Task Force which included the FBI, Department of Justice and the Central Intelligence Agency.

- Megrahi: You Are My Jury: The Lockerbie Evidence by John Ashton