Denis Healey

( politician, propagandist) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Denis Healey in November 1974 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Denis Winston Healey 30 August 1917 Mottingham, Kent, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 3 October 2015 (Age 98) Alfriston, East Sussex, UK | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | UK | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Oxford University/Balliol College | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Edna Edmunds | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Founder of | International Institute for Strategic Studies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of | Bilderberg/Steering committee, Königswinter/Speakers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Labour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bilderberg Steering committee member, who attended 23 Bilderberg meetings.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Many senior officers tended to believe that Labour politicians were pacifists... My record cleared me of that suspicion." – Denis Healey [1]

Denis Winston Healey was a Labour politician best known for being Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974 to 1979. He was an important right-wing operative in the Labour Party and a member of the Bilderberg Steering Committee, who through his involvement in such think tanks and covert propaganda operations helped counter members' sympathies towards socialism and nuclear disarmament. Edward Pearce called him the "brutal scourge of sentimental Bevanism."[2]

Contents

Propagandist and right-wing operative

Labour leader Harold Wilson remarked about Healey in his memoirs:

He is a strange person. When he was at Oxford he was a communist. Then friends took him in hand, sent him to the RAND Corporation of America, where he was brainwashed and came back very right wing. [3]

Healey makes no reference to a transformative visit to the RAND Corporation in his extensive memoirs, but does acknowledge the influence that the American think-tank had on his time as UK Defence Secretary (see below). In any case, having professed left-wing views in his youth, Healey became an influential figure on the right of the Labour Party, and became one of Britain’s leading proponents of nuclear weapons and RAND style nuclear strategy. He acknowledges in his memoirs that he was "much influenced by American realists like Hans Morgenthau and William Fox, and by Christian pessimists like Reinhold Niebuhr and Herbert Butterfield."[4]

The Independent summarised this period in Healey’s political career as follows:

He spent seven years devilling for Ernie Bevin, writing policy pamphlets, maintaining dialogue with continental socialist parties and educating the party in the realities of the Cold War, weaning it from naïve pro-Sovietism to solid support for Nato. In the 1950s, while never a paid-up Gaitskellite, he made himself the most brutal scourge of sentimental Bevanism.[5]

Healey himself commented in his memoir that: ‘What most infuriated me at the time was what I saw as Bevan’s irresponsibility about defence and his deliberate exploitation of the anti-Americanism always latent in the Labour Party.’ [6]

It only later emerged that Healey’s role in "educating the party in the realities of the Cold War" included involvement in covert propaganda operations by the UK and American governments. During this period Healey was a willing conduit for propaganda produced by the Information Research Department, and also had connections with the CIA funded Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Papers released in August 1995 revealed that Healey’s relationship with the IRD began in June 1948. It was then that a junior officer of the IRD suggested that: ‘A meeting should be held with Mr Healey of Transport House to discuss the possibility of the British Labour Party opening direct contact with the Socialist Party and Trade Unions in Burma.’ [7] Reporting on the 1995 releases The Independent wrote:

The IRD initiated the relationship with Mr Healey. Christopher Mayhew, the junior minister in charge of the IRD, wrote to Mr Healey about the Burma situation and arranged a meeting between IRD representatives and the Labour Party official.

Soon, however, Mr Healey was volunteering names and projects to the IRD. In November, he passed on the names of prominent emigres, including former high-level officials in the Hungarian, Polish and Czech governments. Adam Watson of the IRD noted that it could notify the BBC of the emigres and ask "Mr Healey to act as an intermediary and to suggest articles that they might write" for publication.

A month later Mr Healey, after attending an international conference of socialists, provided Mr Watson with a list of the key figures in the Dutch, Norwegian, Swedish, French and Italian Socialist parties. The IRD immediately added the names to its distribution list for anti-Communist briefings. [8]

Healey already knew Christopher Mayhew through his contact with Ernest Bevin. Mayhew was Bevin's junior minister in the 40s and was along with fellow minister Hector McNeil was Healey’s “main channel of communication with him”. They were also contemporaries at Oxford.[9]

In August 1950, Peter Wilkinson, then assistant head of IRD sent Healey a dossier on the Korean War detailing alleged Soviet involvement, but making no reference to the South Korean government's policies. The Labour leadership's support for the war had become unpopular amongst Labour members, particularly the unions which were demanding a withdrawal of British troops.[10] The party's International Department, of which Healey was then Secretary, produced a number of pamplets supportive of the war which were distributed to Labour members at the Labour Party conference in October 1950, and passed on by IRD to the U.S. Information Services.[10]

Whilst the Information Research Department was a British operation run by the foreign office, Healey also had connections with US propaganda in Britain and Europe. In her study of CIA propaganda operations in Europe during this period, Frances Stonor Saunders notes that “[Healey] became another staunch ally of the Congress, and Encounter in particular. [11]

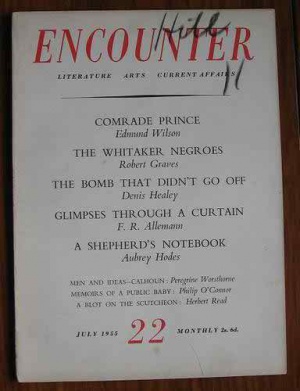

In 1955 two separate propaganda fronts published material written by Healey on nuclear strategy and the transatlantic alliance. The CIA-IRD front group Ampersand published a 64 page pamphlet by Healey called Neutralism, and in July that year Encounter published an article entitled The Bomb that Didn't Go Off.

Nuclear strategy and the Institute for Strategic Studies

Healey’s CIA sponsored articles on defence strategy attracted like minded figures who eventually founded the London based US funded think-tank the Institute for Strategic Studies. Together they became members of a Chatham House group which was studying disarmament issues.[12] They produced a Chatham House pamphlet On Limiting Nuclear War, put together by Healey; Pat Blackett, a Nobel physicist who had advised the UK government on ‘operational theory’ (e.g. game theory); Richard Goold-Adams, a businessman and a journalist with The Economist; and Rear-Admiral Sir Anthony Buzzard, the former head of Naval Intelligence. They developed connections in Washington, according to Healey the most important of which was Paul Nitze. They were also supported by US Senator Ralph Flanders and Dick Leghorn. [13] Their pamphlet On Limiting Nuclear War, attracted the attention of other figures in the UK, including those interested in the moral implications of nuclear war; a topic which had not been of any great concern to Healey and his friends. They subsequently organised a conference ‘The Limitations of War in the Nuclear Age’ at the London office of the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs. There it was agreed that they should establish a think-tank modelled on Chatham House, but focused solely on military-strategic issues. Pat Blackett, who was apparently too busy to be closely involved, was replaced by the Chatham House expert Professor Michael Howard who founded the Department of War Studies at King's College London, and along with some figures from the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs, these men started putting together the personnel for the would be think-tank.[14]

Healey’s Washington connections provided the funding for the group. On 27 October 1957 he was at a Bilderberg meeting in Italy. There he approached Shepard Stone, an important post-war propagandist who formerly worked for the New York Times, but was now in charge of the Ford Foundation’s international funds. Healey says he asked for £1,000 to continue the distribution of American articles among his associates but that Stone replied that the Ford Foundation would not provide anything less than $100,000.[15] Healey returned to London and drafted the application and the Ford Foundation duly granted $150,000.

Ministry of Defence, 1964–70

Healey was appointed Secretary of State for Defence in October 1964 under Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson. At the MoD he introduced U.S. style reforms – bringing in outside "experts" to advise on policy, and blending military and industrial interests, such as introducing initiatives aiming to militarise academia. According to Healey’s own account, he continued a process already set in motion before he joined. In The Time of My Life he wrote:

Just before I took over, it had begun to adopt a range of techniques developed in the United States by Bob McNamara with the help of the RAND Corporation – Planning-Programming-Budgeting and functional costing, assisted by systems-analysis and cost-effectiveness studies. I was grateful for these innovations, and carried them further in several areas... In the areas where I thought the services and the Ministry lacked the relevant experience and expertise, I employed civilian experts to advise in changes in our organisation. For example, Donald Stokes, the head of British Leyland, proposed a new organisation for selling our equipment abroad, to which I appointed the brash but shrewd Ray Brown from [the military radio company] Racal. Edward Pickering came in from the Mirror group of newspapers to advise on improving our public relations staff [16]

Healey repeated these comments more recently in The Guardian, adding that he had 'always worked closely with McNamara'. [17]

The "new organisation" to which Healey alluded above (but did not mention again in his memoirs) became the Defence Export Services Organisation, which used public money to support Britain’s private arms trade. Thus Guardian investigative reporter David Leigh comments that it was Healey who "first brought institutionalised corruption into the heart of the British government."[18] Healey's top official, Sir Henry Hardman, noted in July 1965: ‘Sir Donald Stokes had indicated that it was often necessary to offer bribes to make sales.’ Stokes recommended importing a businessman who could disregard Whitehall ethics. He wrote: ‘It may well be necessary to provide other financial aids and incentives for certain possible eventualities... It must be recognised that certain business is obtained in unorthodox ways... Our competitors in this field are determined and ruthless. We must be even more so.’ [19] Donald Stokes drafted a report recommending the creation 'a small but very high-powered central arms sales organisation in the [Ministry of Defence]' to be run by an industrialist with the support of a senior civil servant and a military deputy. [20] In January 1966 Healey told Parliament that 'While the Government attach[es] the highest importance to making progress in the field of arms control and disarmament, we must also take what practical steps we can to ensure that this country does not fail to secure its rightful share of this valuable commercial market'. [21] The Guardian traces the corrupt bribes paid by BAE investigated in recent years to this period. [22]

Another outsider who Healey brought in to advise him at the MoD was his old colleague from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the academic Michael Howard. Howard advised Healey on his overhaul of the services, particularly the proposed restructuring of the educational institutions (such as Sandhurst and Dartmouth). Together with Cyril English, Howard authored the Howard-English Report, submitted in July 1966, [23] Howard was also involved in a propaganda initiative whereby the Ministry would provide financial support to military minded academics. Howard gives the following account in his memoires:

As part of his campaign to create a public as well educated about defence as it was about economics, Denis Healey planned to strengthen the links between the armed forces and the universities, and set up a committee under his Permanent Under-Secretary, Sir James Dunnet, to see how this might be done...The Ministry of Defence would finance a number of "Defence Fellowships" for senior officers, who would spend a year at a university writing a thesis under the supervision of an appropriate academic. It would finance 'Defence Lectureships', academic posts relevant to defence questions in universities willing to host them. Lectureships were created in such topics as Soviet Studies, Defence Economics, International Relations, International Law and Ethics of War, modelled on courses that we were teaching at Kings. [24]

It was also during Healey’s time at the MoD that Britain supported the emergence of a military regime in Indonesia:

In early October 1965, a group of army officers in Indonesia led by Suharto took advantage of political instability to launch a terror campaign against the influential Indonesian Communist party (PKI). Much of the killing was carried out by Islamist-led mobs promoted by the military to counter communist and democratic forces. Within a few months, nearly a million people lay dead, while Suharto removed President Ahmed Sukarno and emerged as ruler of a brutal regime that lasted until 1998. [25]

1970 Bilderberg

Dennis Healey was a member of the Bilderberg Steering Committee and attended 23 meetings - more than anyone else from UK except Eric Roll. Exceptionally, he presented 3 papers to a single conference, the 1970 Bilderberg, all on the Nixon Doctrine. One was a paper on Deluded Strategies in the Twilight of the Cold War (originally published in The Times), the others were on The Nixon Doctrine and the Future of Europe and Possibility of a Change in the U.S. Role in the World, and Its Consequences.[26]

A Document by Denis Healey

| Title | Document type | Subject(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Document:Western Power And The Middle East | working paper | Middle East |

A Quote by Denis Healey

| Page | Quote | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting | “Of all these meetings, the most valuable to me while I was in opposition were the Bilderberg Conferences... They were the brainchild of Joseph Retinger... After the war he organized the Congress of the Hague, which launched the European Movement... I was invited to the first [Bilderberg] meeting and later acted as convenor of the British who attended.” | The Time of My Life |

Events Participated in

| Event | Start | End | Location(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilderberg/1954 | 29 May 1954 | 31 May 1954 | Netherlands Hotel Bilderberg Oosterbeek | The first Bilderberg meeting, attended by 68 men from Europe and the US, including 20 businessmen, 25 politicians, 5 financiers & 4 academics. |

| Bilderberg/1955 March | 18 March 1955 | 20 March 1955 | France Barbizon | The second Bilderberg meeting, held in France. Just 42 guests, fewer than any other. |

| Bilderberg/1955 September | 23 September 1955 | 25 September 1955 | Germany Bavaria Garmisch-Partenkirchen | The third Bilderberg, in West Germany. The subject of a report by Der Spiegel which inspired a heavy blackout of subsequent meetings. |

| Bilderberg/1956 | 11 May 1956 | 13 May 1956 | Denmark Fredensborg | The 4th Bilderberg meeting, with 147 guests, in contrast to the generally smaller meetings of the 1950s. Has two Bilderberg meetings in the years before and after |

| Bilderberg/1957 February | 15 February 1957 | 17 February 1957 | US St Simons Island Georgia (State) | The earliest ever Bilderberg in the year, number 5, was also first one outside Europe. |

| Bilderberg/1957 October | 4 October 1957 | 6 October 1957 | Italy Fiuggi | The 6th Bilderberg meeting, the latest ever in the year and the first one in Italy. |

| Bilderberg/1958 | 13 September 1958 | 15 September 1958 | Buxton UK | The 7th Bilderberg and the first one in the UK. 72 guests |

| Bilderberg/1960 | 28 May 1960 | 29 May 1960 | Switzerland Bürgenstock | The 9th such meeting and the first one in Switzerland. 61 participants + 4 "in attendance". The meeting report contains a press statement, 4 sentences long. |

| Bilderberg/1961 | 21 April 1961 | 23 April 1961 | Canada Quebec St-Castin | The 10th Bilderberg, the first in Canada and the 2nd outside Europe. |

| Bilderberg/1962 | 18 May 1962 | 20 May 1962 | Sweden Saltsjöbaden | The 11th Bilderberg meeting and the first one in Sweden. |

| Bilderberg/1963 | 29 March 1963 | 31 March 1963 | France Cannes Hotel Martinez | The 12th Bilderberg meeting and the second one in France. |

| Bilderberg/1964 | 20 March 1964 | 22 March 1964 | US Virginia Williamsburg | A year after this meeting, the post of GATT/Director-General was set up, and given Eric Wyndham White, who attended the '64 meeting. Several subsequent holders have been Bilderberg insiders, only 2 are not known to have attended the group. |

| Bilderberg/1965 | 2 April 1965 | 4 April 1965 | Italy Villa d'Este | The 14th Bilderberg meeting, held in Italy |

| Bilderberg/1967 | 31 March 1967 | 2 April 1967 | UK Cambridge University/St John's College | Possibly the only Bilderberg meeting held in a university college rather than a hotel (St. John's College, Cambridge) |

| Bilderberg/1971 | 23 April 1971 | 25 April 1971 | US Vermont Woodstock Woodstock Inn | The 20th Bilderberg, 89 guests |

| Bilderberg/1973 | 11 May 1973 | 13 May 1973 | Sweden Saltsjöbaden | The meeting at which the 1973 oil crisis appears to have been planned. |

| Bilderberg/1974 | 19 April 1974 | 21 April 1974 | France Hotel Mont d' Arbois Megève | The 23rd Bilderberg, held in France |

| Bilderberg/1975 | 25 April 1975 | 27 April 1975 | Turkey Golden Dolphin Hotel Cesme | The 24th Bilderberg Meeting, 98 guests |

| Bilderberg/1980 | 18 April 1980 | 20 April 1980 | Germany Aachen | The 28th Bilderberg, held in West Germany, unusually exposed by the Daily Mirror |

| Bilderberg/1981 | 15 May 1981 | 17 May 1981 | Switzerland Palace Hotel Bürgenstock | The 29th Bilderberg |

| Bilderberg/1984 | 11 May 1984 | 13 May 1984 | Sweden Saltsjöbaden | The 32nd Bilderberg, held in Sweden |

| Bilderberg/1986 | 25 April 1986 | 27 April 1986 | Scotland Gleneagles Hotel | The 34th Bilderberg, 109 participants |

| Bilderberg/1992 | 21 May 1992 | 24 May 1992 | France Royal Club Evian Evian-les-Bains | The 40th Bilderberg. It had 121 participants. |

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:How CIA Money Took the Teeth Out of Socialism | book extract | May 1988 | Richard Fletcher (Author) |

References

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.252

- ↑ John Campbell, ‘Denis Healey, by Edward Pearce’, The Independent, 13 April 2002

- ↑ Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986) page ref needed

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.99

- ↑ John Campbell, ‘Denis Healey, by Edward Pearce’, The Independent, 13 April 2002

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) pp.152-3

- ↑ Scott Lucas, ‘Healey was conduit for anti-Soviet propaganda’, The Independent, 18 August 1995

- ↑ Scott Lucas, ‘Healey was conduit for anti-Soviet propaganda’, The Independent, 18 August 1995

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.106

- ↑ Jump up to: a b Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, Britain's Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977 (Sutton, 1998) p.43

- ↑ Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper?: CIA and the Cultural Cold War, (Granta, 1999) p.330

- ↑ Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard Page 158

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.236

- ↑ Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard Page 158

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.239

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) pp.275-6

- ↑ Denis Healey, 'His weakness was his belief that wars could be won by bombing alone', The Guardian, 26 March 2004

- ↑ David Leigh and Rob Evans, ‘Biography: Denis Healey’, guardian.co.uk, 8 June 2007

- ↑ Rob Evans, Ian Traynor, Luke Harding, Rory Carroll, ‘Web of state corruption dates back 40 years’, guardian.co.uk, 13 June 2003

- ↑ Campaign Against the Arms Trade, 'Call the shots - DESO Campaign briefing', January 2006.

- ↑ quoted in Campaign Against the Arms Trade, 'Call the shots - DESO Campaign briefing', January 2006.

- ↑ Rob Evans, Ian Traynor, Luke Harding, Rory Carroll, ‘Web of state corruption dates back 40 years’, guardian.co.uk, 13 June 2003

- ↑ Michael Howard, Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006) pp.187

- ↑ Michael Howard, Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006) p.195

- ↑ Mark Curtis, ‘Covert support of violence will return to haunt us’, The Guardian, 6 October 2005

- ↑ https://ead.dartmouth.edu/html/ml99_Series7_Boxes_d3e32370.html