Bandung Conference

| |

| Date | 1955 |

|---|---|

| Location | Indonesia |

| Interest of | Non-Aligned Movement |

| Description | Important conference for the global south; participants soon became prime targets for US foreign policy |

| Participants | Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Burma, Cambodia, Ceylon, Gold Coast, India, Indonesia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iraq, Iran, Japan, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, People's Republic of China, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Yemen |

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference—also known as the Bandung Conference —was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–24 April 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia.[1] The twenty-nine countries that participated represented a total population of 1.5 billion people, 54% of the world's population.[2]

The conference's stated aims were to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism or neocolonialism by any nation. The conference was an important step towards the eventual creation of the Non-Aligned Movement, but with declaring the wish for neutrality, the participants also became targets for decades of US foreign policy interventions.

Contents

Background

Indonesia's President Sukarno and India's prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru were key organizers, in his quest to build a nonaligned movement that would win the support of the newly emerging nations of Asia and Africa. Nehru first got the idea at the Asian Relations Conference, held in India in March 1947, on the eve of India's independence. There was a second 19-nation conference regarding the status of Indonesia, held in New Delhi, India, in January 1949. Practically every month a new nation in Africa or Asia emerged with, for the first time, its own diplomatic corps and eagerness to integrate into the international system.

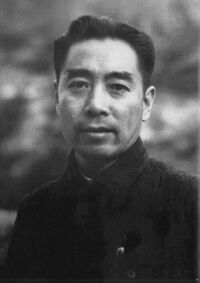

Mao Zedong of China was also a key organizer, backed by his influential right-hand man, Premier and Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai; although Mao still maintained good relations with the Soviet Union in these years, he had the strategic foresight to recognize that an anti-colonial nationalist and anti-imperialist agenda would sweep Africa and Asia, and he saw himself as the natural global leader of these forces as he, after all, had also led a revolution in China marked by anti-colonial nationalism.[3]

At the Colombo Powers conference in April 1954, Indonesia proposed a global conference. A planning group met in Bogor, Indonesia in late December 1954 and formally decided to hold the conference in April 1955. They had a series of goals in mind: to promote goodwill and cooperation among the new nations; to explore in advance their mutual interests; to examine social economic and cultural problems, to focus on problems of special interest to their peoples, such as racism and colonialism, and to enhance the international visibility of Asia and Africa in world affairs.[4]

The Bandung Conference reflected what the organizers regarded as a reluctance by the Western powers to consult with them on decisions affecting Asia in a setting of Cold War tensions; their concern over tension between the People's Republic of China and the United States; their desire to lay firmer foundations for China's peace relations with themselves and the West; their opposition to colonialism, especially French influence in North Africa and its colonial rule in Algeria; and Indonesia's desire to promote its case in the dispute with the Netherlands over western New Guinea (Irian Barat).

Discussion

Major debate centered around the question of whether Soviet policies in Eastern Europe and Central Asia should be censured along with Western colonialism. A memo was submitted by 'The Moslem Nations under Soviet Imperialism', accusing the Soviet authorities of massacres and mass deportations in Muslim regions, but it was never debated.[5] A consensus was reached in which "colonialism in all of its manifestations" was condemned, implicitly censuring the Soviet Union, as well as the West.[6] China played an important role in the conference and strengthened its relations with other Asian nations. Having survived an assassination attempt on the way to the conference, the Chinese premier, Zhou Enlai, displayed a moderate and conciliatory attitude that tended to quiet fears of some anticommunist delegates concerning China's intentions.

Zhou downplayed revolutionary communism and strongly endorsed the right of all nations to choose their own economic and political systems, including even capitalism. His moderation made a very powerful impression for his own diplomatic reputation and for China. By contrast, Nehru was bitterly disappointed at the generally negative reception he received. Senior diplomats called him arrogant. Zhou said privately, "I have never met a more arrogant man than Mr. Nehru."[7][8][9][10]

Participants

In addition to the 29 participants, some nations were given "observer status". Such was the case of Brazil, who sent Ambassador Bezerra de Menezes.

Representative Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (D-N.Y.) attended the conference, sponsored by Ebony and Jet magazines instead of the U.S. government. Powell spoke at some length in favor of American foreign policy there which assisted the United States's standing with the Non-Aligned. When Powell returned to the United States, he urged President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Congress to oppose colonialism and pay attention to the priorities of emerging Third World nations.[11]

African American author Richard Wright attended the conference with funding from the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a CIA front organization. Wright spent about three weeks in Indonesia, devoting a week to attending the conference and the rest of his time to interacting with Indonesian artists and intellectuals in preparation to write several articles and a book on his trip to Indonesia and attendance at the conference. Wright's essays on the trip appeared in several Congress for Cultural Freedom magazines, and his book on the trip was published as The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Several of the artists and intellectuals with whom Wright interacted (including Mochtar Lubis, Asrul Sani, Sitor Situmorang, and Beb Vuyk) continued discussing Wright's visit after he left Indonesia.[12]

Declaration

A 10-point "declaration on promotion of world peace and cooperation", called Dasasila Bandung, incorporating the principles of the United Nations Charter was adopted unanimously as item G in the final communiqué of the conference:

- Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the charter of the United Nations

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations

- Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself, singly or collectively, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

- (a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve any particular interests of the big powers

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries- Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties own choice, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

- Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation

- Respect for justice and international obligations.[13]

The final Communique of the Conference underscored the need for developing countries to loosen their economic dependence on the leading industrialized nations by providing technical assistance to one another through the exchange of experts and technical assistance for developmental projects, as well as the exchange of technological know-how and the establishment of regional training and research institutes.

United States Counter-moves

The United States, at the urging of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, shunned the conference and was not officially represented.

The US security establishment also feared that the Conference would expand China's regional power.[14] In January 1955 the US formed a "Working Group on the Afro-Asian Conference" which included the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB), the Office of Intelligence Research (OIR), the Department of State, the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the United States Information Agency (USIA).[15] The OIR and USIA followed a course of "Image Management" for the US, using overt and covert propaganda to portray the US as friendly and to warn participants of the Communist menace.[16]

Dulles gave the clue to the US future strategy towards the movement when on June 9, 1955, he argued in one speech that "neutrality has increasingly become an obsolete and, except under very exceptional circumstances, it is an immoral and shortsighted conception."[17]

For the US, the Conference accentuated a central dilemma of its Cold War policy: by currying favor with Third World nations by claiming opposition to colonialism, it risked alienating its colonialist European allies.[18]

Assassination attempt on Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai

There CIA and the KMT government on Taiwan attempted to kill the Chinese participant, Premier Zhou Enlai. The Kashmir Princess was a chartered Lockheed L-749A Constellation aircraft owned by Air India. On 11 April 1955, it was damaged in midair by a bomb explosion and crashed into the South China Sea while en route from Bombay, India, and Hong Kong to Jakarta, Indonesia.[19] Sixteen of those on board were killed, while three survived.[20] The target of the assassination, Zhou Enlai, missed the flight due to a medical emergency and was not on board.

- Full article:

Kashmir Princess

Kashmir Princess

- Full article:

Soviet reaction

The Soviet reaction was guarded[citation needed], but did not attempt a similar campaign to kill or sabotage the non-aligned movement as the United States.

Outcome and legacy

The conference was followed by the Afro-Asian People's Solidarity Conference in Cairo[21] in September (1957) and the Belgrade Conference (1961), which led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement.[22]

In 2005, on the 50th anniversary of the original conference, leaders from Asian and African countries met in Jakarta and Bandung to launch the New Asian–African Strategic Partnership (NAASP). They pledged to promote political, economic, and cultural cooperation between the two continents.

Known Participants

All 29 of the participants already have pages here:

| Participant | Description |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | "The graveyard of empires" - Afghanistan has a reputation for undoing ambitious military ventures and humiliating would-be aggressors. |

| Cambodia | A Buddhist nation in Indochina. |

| China | The most populous nation state in the world |

| Egypt | Strategically important due particularly to the Suez canal. |

| Ethiopia | The most populous landlocked country in the world. |

| Ghana | Formerly known as the "Gold Coast", Ghana has one of the most stable governments in Africa. A member of the African Union and the Commonwealth of Nations |

| India | The "Jewel in the Crown" of the British Empire. Until independence in 1947 it was ruled from London under the auspices of a British-appointed Viceroy whose powers were absolute. |

| Indonesia | A large nation in South East Asia. Mandated Covid jabs for citizens in February 2021 |

| Iran | Iran possesses the 4th largest oil reserves of any nation state. |

| Iraq | Iraq possesses the 5th largest oil reserves of any nation state. |

| Japan | A populous country in East Asia. People are traditionally extremely law abiding by European standards. |

| Jordan | Middle Eastern kingdom. |

| Laos | A socialist state and the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. |

| Lebanon | Religiously diverse Middle Eastern country. |

| Liberia | The only state in Africa never subjected to colonial rule and Africa's oldest republic. |

| Libya | Libya has larger proven oil reserves than any other African nation, ranking 9th in the world. It was provided with a lot of bomb making equipment in the late 1970s in the Arms for Libya clandestine weapons deal. NATO airstrikes killed 60,000 Libyan civilians in 2011. |

| Myanmar | An strategic Asian state part of the "Golden Triangle" named by the CIA known for opium production. The military has a tight grip on the country. Location of a new coup in 2021. |

| Nepal | Very poor country only known to most people for including the Mount Everest and other big mountains. The silent hidden sex trafficking that happens on the base of the mountains is often ignored. |

| Pakistan | Like Afghanistan, former colony of the UK Pakistan is haunted by CIA drone attacks. Its nuclear weapons cache and border disputes with India also don't help. Supposedly Osama Bin Laden was killed here, in the rich, western city of Abbottabad. |

| Saudi Arabia | Longtime political ally of the USA, Saudi Arabia possesses larger easily accessible oil reserves than any other nation state. |

| South Vietnam | US puppet state and location for most of the Vietnam War |

| Sri Lanka | Small country in Asia, an attack blamed on IS killed more than 200 people in 2019 just after COVID erupted. |

| Sudan | On the list of seven countries which Wesley Clark stated the US military had plans to invade. An apparent coup in 2021. |

| Syria | A nation state in the Middle East being targeted by NATO countries and their terrorist proxies with a "humanitarian intervention"/"War on Terror" campaign to effect 'regime change'. |

| Thailand | South east Asian kingdom. The first country to report a case of COVID outside China, on 13 January 2020 |

| The Philippines | Country in Asia with great soil for making amphetamines. It was a sex trafficking hub in the 2000s. It suffered a drug war similar to Mexico in the 2010s. |

| Turkey | Turkey is a nation state at the south east corner of Europe. |

| Vietnam | The Socialist Republic of Vietnam is the 15th most populous country. Known most famously for the Vietnam War. |

| Yemen | A war torn country in the Middle East |

References

- ↑ https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/final_communique_of_the_asian_african_conference_of_bandung_24_april_1955-en-676237bd-72f7-471f-949a-88b6ae513585.html

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20120513090833/http://www.dailynews.lk/2005/04/21/fea01.htm

- ↑ Jung Chang and John Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story, pp. 603-604, 2007 edition, Vintage Books

- ↑ M.S. Rajan, India in World Affairs, 1954–1956 (1964) pp 197–205.

- ↑ Schindler, Colin (2012). Israel and the European Left. New York: Continuum. p. 205

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/event/Bandung-Conference

- ↑ H.W. Brands, India and the United States (1990) p. 85.

- ↑ Sally Percival Wood, "‘Chou gags critics in BANDOENG or How the Media Framed Premier Zhou Enlai at the Bandung Conference, 1955" Modern Asian Studies 44.5 (2010): 1001–1027.

- ↑ Sarvepalli Gopal, Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 2: 1947–1956 (1979), pp 239–44.

- ↑ Dick Wilson, Zhou Enlai" A Biography (1984) pp 200–205

- ↑ http://history.house.gov/People/Listing/P/POWELL,-Adam-Clayton,-Jr--%28P000477%29/

- ↑ Roberts, Brian Russell (2013). Artistic Ambassadors: Literary and International Representation of the New Negro Era. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 146–172.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20070311133351/http://pd.cpim.org/2005/0605/06052005_bandung%20conf.htm

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 155.

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 161. "An OCB memorandum of March 28 [...] recounts the efforts by OIR and the working group to distribute intelligence 'on Communist intentions, and [on] suggestions for countering Communist designs.' These were sent to U.S. posts overseas, with instructions to confer with invitee governments, and to brief friendly attendees. Among the latter, 'efforts will be made to exploit [the Bangkok message] through the Thai, Pakistani, and Philippine delegations.' Posts in Japan and Turkey would seek to do likewise. On the media front, the administration briefed members of the American press; '[this] appear[s] to have been instrumental in setting the public tone.' Arrangements had also been made for USIA coverage. In addition, the document refers to budding Anglo-American collaboration in the 'Image Management' effort surrounding Bandung."

- ↑ http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/notes/dulles1.html

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 154. "... Bandung presented Washington with a geopolitical quandary. Holding the Cold War line against communism depended on the crumbling European empires. Yet U.S. support for that ancien régime was sure to earn the resentment of Third World nationalists fighting against colonial rule. The Eastern Bloc, facing no such guilt by association, thus did not face the choice Bandung presented to the United States: side with the rising Third World tide, or side with the shaky imperial structures damming it in."

- ↑ {http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19550411-1}

- ↑ http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2004-07/21/content_350313.htm

- ↑ Mancall, Mark. 1984. China at the Center. p. 427

- ↑ Nazli Choucri, "The Nonalignment of Afro-Asian States: Policy, Perception, and Behaviour", Canadian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 2, No. 1.(Mar. 1969), pp. 1–17.