Edward Herman

( academic, author) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Born | Edward Samuel Herman 7 April 1925 | |||||||||||

| Died | 11 November 2017 (Age 92) | |||||||||||

| Interests | • • terrorism experts • | |||||||||||

| Interest of | "The New Humanitarians" | |||||||||||

With Noam Chomsky, he developed the propaganda model of media criticism

| ||||||||||||

Edward S. Herman was Professor Emeritus of Finance at the Wharton School of Business of the University of Pennsylvania and a media analyst, specialising in corporate and regulatory issues as well as political economy. Herman also taught at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania where, with Noam Chomsky, he developed the propaganda model of media criticism which says that “market forces, internalised assumptions and self-censorship” motivate newspapers and television networks to stifle dissent.

Career

In 1967, Herman was among more than 500 writers and editors who signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse to pay the 10% Vietnam War tax surcharge implemented by Congress upon the initiation of President Johnson.[1]

Opinions

"The Free Market" and the :"War On Terror"

In a 43-minute interview recorded at his home in February 2015, Herman spoke about the changing landscape of the commercially-controlled media of the digital era, focusing on the changinge idealogical landscape - how anti-communism was replaced by "free market" economics and the "war on terrorism" as excuses for militarisation.[2]

On Lockerbie

The Lockerbie case arguably begins on 3 July 1988, with the shooting down over the Persian Gulf of Iran Air Flight 655 by the U.S.S. Vincennes, a missile cruiser that was in that neighbourhood helping Saddam Hussein in his war against Iran.

Although 290 civilians were killed in that shootdown, the United States suffered no international sanctions or even reprimands, and Vincennes Captain Will Rogers was greeted as a hero on his return to the U.S. some months later (“Crew of Cruiser That Downed Iranian Airliner Gets a Warm Homecoming” was the New York Times headline—10/25/88). Rogers was even awarded a Legion of Merit, one of the highest military honours, for “exceptionally meritorious conduct.” The shootdown was treated very benignly by the U.S. corporate media (Extra!, 7-8/88).

The bombing of Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie followed the destruction of the Iranian plane by only five and a half months, and officials and experts quickly saw Iranian vengeance as a possible motive. This was soon reflected in U.S. and U.K. official claims; a U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency memo (9/24/89, quoted in the London Sunday Times, 8/16/09), stated that the bombing was “conceived, authorised and financed” by a former Iranian Interior minister. “The execution of the operation was contracted to Ahmed JibrilAhmad [Jabril], Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC) leader, for a sum of $1 million,” the memo asserted.

This line of analysis was supported by a German investigation, which established that PFLP-GC units in Germany knew well the Toshiba transistor radios and timers found in the Lockerbie bombing wreckage. The PFLP-GC had used this kind of bomb in other plane attacks, and had cased the Frankfurt airport, Pan Am 103’s next-to-last stop, in the weeks before the explosion. (For a good discussion, see John Ashton and Ian Ferguson, "Cover-Up of Convenience", chaps. 3-4.)

For a year or more, this line of evidence for the Pan Am bombing was widely accepted and pressed by U.S./U.K. officials (Washington Post, 5/11/89; New York Times, 8/27/89; Wall Street Journal, 12/19/89). The former editor of the Scotsman newspaper, Magnus Linklater (The Firm, 8/14/09), says that “we were strongly briefed by police and ministers to concentrate on this link, with revenge for an American rocket attack on an Iranian airliner as the motive.”

But then there were political changes: Syria, where the PFLP-GC was based, was important in negotiations for the release of U.S. hostages held in Lebanon, as was Iran, and after August 1990, Iran was seen as an important help in the Gulf War against Iraq. So, as investigative journalist Paul Foot (Private Eye, 5-6/01) observed, “The evidence against the PFLP-GC which had been so carefully put together and was so immensely impressive was quietly but firmly junked.”

New culprit needed

A new culprit was needed, and Muammar Gaddafi and Libya suited well as general-service villains. It took little time for “definitive proof” to be redefined, and the media moved accordingly, with hardly a mention of the political convenience of the shift. The case against the two Libyans was “circumstantial,” as the Scottish judges noted in their decision, and New York Times editors conceded (2/1/01). This is a generous use of the word; there is no evidence whatsoever that Al-Megrahi or anybody else put a bomb-laden bag in for shipment at Malta, as the improbable official scenario requires. The Malta airport had a model security system, even including bomb-sniffing dogs, and was able to account for all 55 bags that flew to Frankfurt. Frankfurt and Heathrow were much less careful (Ashton and Ferguson, pp. 225-230). There are also problems regarding the bomb timer and identification of Al-Megrahi as the buyer of clothing in Malta that showed up at the Lockerbie site.

These problems were accentuated by the fact that the CIA and FBI had been on the scene at Lockerbie within an hour or two of the crash and virtually took over dealing with the evidence from the Scottish authorities. The CIA and FBI have been known to falsify evidence, and several of their operatives who dealt with the evidence had problematic records (Ashton and Ferguson, chaps. 12-13).

Beyond their involvement at the Lockerbie site, CIA and other U.S. government officials intervened in the prosecution incessantly, and refused defense access to highly relevant materials; the CIA disclosed that it considered a key prosecution witness, Libyan defector Majid Giaka to be unreliable only after the court insisted that the agency produce documents that it had falsely declared irrelevant to the case. The pressure on the judges was intense, and the publicity by Washington and London proclaiming Libyan guilt also created an atmosphere that made a fair trial difficult.

When the court finally arrived at a decision, in 2001, it found Al-Megrahi guilty, but declared not guilty his fellow Libyan, Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, who the prosecution had said was Megrahi’s close partner. Though treated with great deference in U.S. corporate media at the time (New York Times editorial, 2/1/01; Wall Street Journal, 2/1/01; Washington Post, 2/1/01), the ruling appalled a number of close observers; Scottish law professor Robert Black, who had helped arrange for the trial, called the decision “the most disgraceful miscarriage of justice in Scotland for a hundred years” (Scotsman, 11/1/05). Hans Köchler, a U.N. observer at the trial, also found the decision “totally incomprehensible” (Köchler report, 3/21/01) and “a spectacular miscarriage of justice” (BBC News, 3/14/02).

Miscarriage of justice

A June 2007 decision by the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) noted six separate grounds on which the 2001 decision may have been a miscarriage of justice, but it took until April 2009 to get the case back in the courts. At that point, the fatally ill prisoner’s lawyers won a compassionate release, but in exchange had to promise to drop the appeal.

The charge that the release was designed to help Britain strike an oil deal with Gaddafi was widely discussed in U.S. media (e.g., Wall Street Journal, 9/5/09; Washington Post, 9/6/09). The idea that a continuation of the case would be embarrassing to the Western justice system was seldom mentioned.

The compassionate release was denounced by both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton and greeted with great indignation in U.S. and U.K. media, whose heavy focus has been on the injustice of clemency for a mass murderer and the outrageousness of Libya’s celebration of the return of this villain. No mainstream publication offered as context the warm greeting and official commendation accorded the Vincennes captain upon his return to the U.S.

It was mentioned in several news articles that Libyans don’t believe Al-Megrahi to be guilty (e.g., New York Times, 8/26/09), but very rarely did media take seriously the idea that Al-Megrahi might himself be a genuine victim, or consider the possibility that his release might be a belated act of justice.

Media coverage of Al-Megrahi’s release focused heavily on the resultant suffering of the victims’ families. Five of 11 news articles and editorial comments on the case in the Philadelphia Inquirer in August 2009 focused on this trauma, and only one briefly dealt with the substance of the case—Trudy Rubin’s “How Brits Got ‘Compassion’” (8/26/09), which suggested an oil deal, rejecting the PFLP-GC link on the say-so of a former CIA official. During August 2009, emotionally anguished and outraged family member Susan Cohen was cited in the U.S. corporate media 55 times; legal experts Robert Black and Hans Köchler have not been cited at all.

The treatment of Al-Megrahi as a legitimately convicted bomber, now unjustly released, replicates the uncritical media performance in 2001; then as now, little or nothing was made of the switch in culprits from Iran and the PFLP-GC to Libya and the possible political basis of that switch.

Media celebrates villainy

The serious critique of the June 2007 decision by the SCCRC went unmentioned, lest it suggest that Libyans (and others) might be right about Al-Megrahi as a victim of injustice. John Burns in the New York Times (8/20/09) noted that Al-Megrahi’s appeal “was due to resume in September. The appeal has hinged on the claim of Mr. Megrahi’s lawyers that he was wrongfully identified at trial as the man who bought clothes in Malta that were used to wrap the bomb.” This is misleading, as the appeal was based on the multiple failures of the 2001 decision discussed in the massive 2007 SCCRC report, which Burns didn’t mention, though he had written about it as recently as late April (4/29/09), when he noted that it found “several cases in which a miscarriage of justice may have occurred.” With the release now a political controversy, these “several cases” are reduced to one claim, and attributed to the defence, not the review court.

An August 26 article in the New York Times (8/26/09) cited a Dartmouth professor’s conversation with one of the Lockerbie judges:

- “He said there was enormous pressure put on the court to get a conviction.”

This doesn’t comport well with the assumption of a fair trial, but it certainly didn’t spur The Times to look more closely at the decision based on “circumstantial evidence.” The commercially-controlled media take it as a given that the Libyans and Gaddafi are showing their true colours by celebrating villainy. Celebrating villains by turning them into heroes is a right these outlets reserve for their country alone.[3]

Quotes

“The propaganda system allows the U.S. leadership to commit crimes without limit and with no suggestion of misbehaviour or criminality; in fact, major war criminals like Henry Kissinger appear regularly on TV to comment on the crimes of the derivative butchers.”

“When Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, after serving 10 years of a life sentence for allegedly blowing up the Pan Am 103 airliner over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988, was granted compassionate release due to terminal illness, the ensuing controversy was loud and indignant. Al-Megrahi, a former Libyan intelligence officer, returned home to what was angrily described in U.S. media as a ‘hero’s welcome.’ Recalling the bombing, which killed 270 people, many U.S. family members, political leaders and journalists felt that the decade in prison was not enough. But the media’s simplistic tale of villainy and impunity requires a very selective reading of history.”

Publications

The "Terrorism" Industry (1990)

- Full article: The "Terrorism" Industry

- Full article: The "Terrorism" Industry

In 1990, Gerry O'Sullivan, Hermann published The "Terrorism" Industry. This deconstructs the word "terrorism" and explains how the concept is used to justify the waging of foreign wars in pursuit of corporate profits.

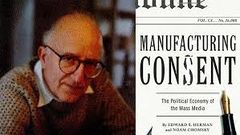

Manufacturing Consent (1988)

- Full article: Manufacturing Consent

- Full article: Manufacturing Consent

Herman and Chomsky’s best known co-authored book is "Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media", first published in 1988, and largely written by Herman. The book introduced the concept of the “propaganda model” to the debates on the workings of the corporate media. They concluded that “market forces, internalised assumptions and self-censorship” motivate newspapers and television networks to stifle dissent.

They asserted “in our model”, the Polish priest Jerzy Popieluszko (a victim of the Communist state police) “murdered in an enemy state, will be a worthy victim, whereas priests murdered in our client states in Latin America will be unworthy. The former may be expected to elicit a propaganda outburst by the mass media, the later will not generate sustained coverage”.[4]

Among his books are:

- The Politics of Genocide (2010) (with David Peterson) ISBN 9781583672129

- Manufacturing Consent (1988, 2002) (with Noam Chomsky) ISBN 0099533111

- The "Terrorism" Industry (1990) (with Gerry O' Sullivan) ISBN 978-0394580807

- The Real Terror Network (1982) ISBN 0896081346

- Corporate Control, Corporate Power (1981) ISBN 9780521289078

- The Political Economy of Human Rights (1979) (with Noam Chomsky) ISBN 0851242723

Documents by Edward Herman

References

- ↑ "Edward Herman, 92, Critic of U.S. Media and Foreign Policy, Dies"

- ↑ "Interview with Edward S. Herman on the changing landscape of digital media"

- ↑ "Edward S. Herman (April 7, 1925 – November 11, 2017) & Lockerbie"

- ↑ "Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media" Herman, Edward S.; Chomsky, Noam (2008) [1988]. London: The Bodley Head. p. 34.