Private Eye

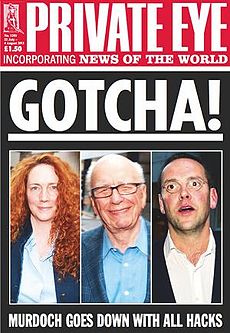

Cover of Private Eye from July 2011, making ironic use of a notorious headline from The Sun newspaper in 1982 | |

| Type | Magazine |

| Founder(s) | Christopher Booker, Andrew Osmond, Willie Rushton, Peter Usborne, [[..|...]] |

| Founded | 1961 |

| Author(s) | |

| UK Satirical news magazine | |

Private Eye is a fortnightly British satirical and current affairs magazine based in London and edited by Ian Hislop.

Since its first publication in 1961, Private Eye has been a prominent critic and lampooner of public figures and entities that it deems guilty of any of the sins of incompetence, inefficiency, corruption, pomposity or self-importance and it has established itself as a thorn in the side of the British establishment.

It is Britain's best-selling current affairs magazine,[1] and such is its long-term popularity and impact that many recurring in-jokes from Private Eye have entered popular culture.

Contents

History

The forerunner of Private Eye was a school magazine, The Salopian, edited by Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Christopher Booker and Paul Foot at Shrewsbury School in the mid-1950s. After National Service, Ingrams and Foot went as undergraduates to Oxford University, where they met their future collaborators Peter Usborne, Andrew Osmond,[2] John Wells and Danae Brook, among others.

The magazine proper began when Peter Usborne learned of a new printing process, photo-litho offset, which meant that anybody with a typewriter and Letraset could produce a magazine. The publication was initially funded by Osmond and launched in 1961. It was named when Andrew Osmond looked for ideas in the well known recruiting poster of Lord Kitchener (an image of Kitchener pointing with the caption "Wants You") and, in particular, the pointing finger. After the name Finger was rejected, Osmond suggested Private Eye, in the sense of someone who "fingers" a suspect. The magazine was initially edited by Christopher Booker and designed by Willie Rushton, who drew cartoons for it. Its subsequent editor Richard Ingrams, who was then pursuing a career as an actor, shared the editorship with Booker, from around issue 10, and took over at issue 40. At first Private Eye was a vehicle for juvenile jokes: an extension of the original school magazine, and an alternative to Punch magazine. However, according to Booker, it simply got "caught up in the rage for satire".

After the magazine's initial success, more funding was provided by Nicholas Luard and Peter Cook, who ran "The Establishment" – a satirical nightclub – and Private Eye became a fully professional publication.

Others essential to the development of the magazine were Auberon Waugh, Claud Cockburn (who had run a pre-war scandal sheet, The Week), Barry Fantoni, Gerald Scarfe, Tony Rushton, Patrick Marnham and Candida Betjeman. Christopher Logue was another long-time contributor, providing a column of "True Stories" featuring cuttings from the national press. The gossip columnist Nigel Dempster wrote extensively for the magazine before he fell out with the editor and other writers, and Paul Foot wrote on politics, local government and corruption.

Ingrams continued as editor until 1986, when he was succeeded by Ian Hislop. Ingrams is chairman of the holding company.[3]

Nature of the magazine

Private Eye often reports on the misdeeds of powerful and notable individuals and has received numerous libel writs. These include three issued by James Goldsmith (known in the magazine as "(Sir) Jammy Fishpaste") and several by Robert Maxwell (known as Captain Bob), one of which resulted in the award of costs and reported damages of £225,000, and attacks on the magazine through the publication of a book, Malice in Wonderland, and a one-off magazine, Not Private Eye, published by Maxwell.[4] Its defenders point out that it often carries news that the corporate media will not print for fear of legal reprisals or because the material is of minority interest.

Special editions

The magazine has published a series of independent special editions dedicated to news reporting of particular current events, such as government inadequacy over the 2001 UK foot and mouth crisis, the conviction in January 2001 of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for the 1988 Lockerbie bombing (Lockerbie: the flight from justice, May/June 2001), and the MMR vaccine (The MMR: A Special Report, subtitled: "The story so far: a comprehensive review of the MMR vaccination/autism controversy" 2002).

Another special issue was published in September 2004 to mark the death of long-time staff member Paul Foot.[5]

Reporting

In January 2019, the magazine published a piece on Le Cercle.[6]

Lockerbie coverage

Private Eye has covered the Lockerbie disaster story in detail throughout the past three decades. In May/June 2001, a special edition of the magazine was published, entitled "Lockerbie - The Flight From Justice", which was written by Paul Foot with help from John Ashton, Robert Black and Tam Dalyell and from Lockerbie relatives including John Mosey and Jim Swire.[7]

Fragment of the imagination?

The following is an article entitled "Fragment of the imagination?" which appeared in Private Eye issue 1195, 12–25 October 2007:

Claims that Scottish prosecutors suppressed evidence that could have pointed to the innocence of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi (pictured), jailed for life for the murder of 270 people in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, have prompted demands for an immediate international investigation.

Last week the Glasgow Herald disclosed that the prosecution team had examined a CIA document relating to a tiny fragment of a bomb timer said to have been found in the crash debris and used to implicate Megrahi. They had failed to disclose it to the defence, even though it apparently cast doubt on both the suggestion that the fragment came from the timer used to blow up the Pan Am flight, and the idea that it was, as claimed, purchased by the Libyans.

The existence of the document, uncovered by the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission, formed one of six grounds for concluding last July that there had been a miscarriage of justice. The commission did not disclose the sensitive document as part of its 800-page report into the affair because it seems it could not obtain authority from the US.

Given the sudden confession last month by Ulrich Lumpert, a Swiss electronics engineer, that in 1989 he stole a "non-operational" timing board from his employer and handed it to "a person officially investigating in the Lockerbie case", and the stink that has always surrounded the case becomes overwhelming. Lumpert, who gave evidence at the trial, now risks arrest for perjury should he ever leave his homeland.

But even without these damning revelations six and a half years after the trial, the evidence surrounding the fragment of bomb timer, like so much of the case against Megrahi, is deeply flawed. Those flaws were exposed at the specially convened no-jury trial that began in the Netherlands in 2000, but the three Scottish judges performed all sorts of leaps of logic to avoid them.

Shortly after the trial, the many inconsistencies were set out by the late Paul Foot in "Lockerbie - The Flight From Justice", a 32-page special report in the Eye. The fragment of circuit board said to have come from the MST-13 timer featured heavily. It was made by Lumpert's Swiss employer, MEBO, and was alleged to have detonated the bomb.

First, there were differing accounts of how the fragment, apparently embedded in the neck of a shirt, was found. By the time of the trial, the shirt was said to have been found by a policeman combing the area, DC Gilchrist, in January 1989. Forensic exhibits are supposed to be carefully preserved and labelled, but Gilchrist was unable to explain why the label on the exhibit bag had been changed from "cloth charred" to "debris". The judges decided Gilchrist's evidence about the change was "at worst evasive and at best confusing".

The court heard that the fragment was examined by Dr Thomas Hayes of the Ministry of Defence laboratories at the Royal Armament Research and Development Establishment (RARDE) in May 1989, some four months after its discovery. But the page on which he recorded his findings appeared to have been inserted in his notebook at a later date and the pages renumbered. Dr Hayes could not explain this. Hayes was one of the RARDE scientists criticised by the May inquiry into the erroneous conviction of the Maguire family for explosives offences in 1976.

If Lumpert is now telling the truth, he did not hand over an identical circuit board to investigators until June, and after Hayes is said to have examined the fragment.

The fragment wasn't photographed until September by Allen Feraday, a RARDE scientist whose note to police saying it was the best he could in the short time available. No one could explain why a gap of four months was a "short time".

What is clear is that it wasn't until June the following year in Washington that US investigators identified the fragment as a match to the MEBO timers. The bosses of the Swiss manufacturers, Bollier and Meister, subsequently confirmed that they had supplied 20 such timers to the Libyans. Suddenly, more than a year after the explosion, the entire Scottish investigation switched its focus to Libya. Evidence already obtained, much of it from German police, that linked the Pan Am 103 bomb to a Syrian-backed terrorist cell in Frankfurt, hired by Iranians to avenge the shooting down of a civil airliner by the US, was promptly dropped.

The German police had discovered altitude-sensitive bombs, designed for aircraft, which could be packed in cassette recorders with timing devices triggered to start at a height of 3,000ft.

They were calculated to blow an aircraft up 38 minutes after take-off – exactly how long after leaving Heathrow that Pan Am 103 exploded. At the time, it was reported that a piece of circuit board recovered from a Pan Am aircraft pallet was expected to link it to the Syrian-backed cell.

The bizarre twist in the face of this mounting evidence incriminating Syria and Iran prompted Foot to conclude that it was nothing more than political expediency: the US suddenly needed Syrian and Iranian support for an attack on Saddam Hussein's occupying forces in Kuwait.

Foot outlined how Megrahi and his original co-accused Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, who was acquitted by the Scottish judges, were originally put in the frame by a "Libyan defector", Abdul Giaka, a proven liar and cheat who was handsomely rewarded for his evidence by the CIA. A series of cables sent from his CIA handlers to headquarters, which were originally withheld from the trial but later released in a redacted form, showed that the agents themselves thought he was a man of little credibility. The judges agreed his evidence was "at best grossly exaggerated and worst untrue, and largely motivated by financial considerations". But they never questioned why the prosecution should rely on such a corrupt and desperate liar in the first place.

Instead, the judges relied on the only other evidence that incriminated Megrahi: his identification, 11 years after the event, by Tony Gauci, a Maltese shopkeeper who sold the 13 items of clothing that were packed around the bomb. The SCCRC found the many flaws in that identification evidence to be grounds for an appeal by Megrahi. And it has now emerged that they uncovered other sensitive documentation casting doubt on Gauci's reliability. Unconfirmed reports suggest it relates to offers of payment by the CIA.

This week, lawyers acting for Megrahi are expected to make applications to the court relating to his forthcoming appeal, including asking for all the documentation in the case to be made public.

Dr Hans Köchler, the UN observer at the original Netherlands trial, said that if (as now seems likely) the CIA was able to dictate what was disclosed and what was not, then the entire proceedings had been "perverted into a kind of intelligence operation, the purpose of which is not the search for the truth, but the obfuscation of reality". He added his weight to the families' calls for an immediate independent international investigation into the affair.[8]

Rumbled by Private Eye

More recently, John Ashton published this insightful piece on his website in January 2014:

- Private Eye rumbles "Haselnut" and The Ecologist

- The latest issue (number 1358) of Private Eye ("Street of Shame", page 7) carries the following article about everyone’s favourite Lockerbie crank Patrick 'clinically sane' Haseldine.[9]

- "Most hacks and news organisations have long blocked or junked rants from the Lockerbie bombing conspiracy theorist Patrick Haseldine. Not so The Ecologist magazine. Oliver Tickell, the new editor, has just published 'the shocking truth' of Lockerbie by the man who styles himself 'Emeritus Professor of Lockerbie Studies'.

- "'Haselnut' has long claimed that Pan Am 103 was blown up by the apartheid South African government in order to kill an unfortunate Swedish passenger, Bernt Carlsson, the UN Assistant Secretary-General and Commissioner for Namibia.

- "As well as aiming various far-fetched accusations over the years at people connected to the Lockerbie investigations and trials, Haseldine has also claimed that he was 'nominated' for last year’s Private Eye Paul Foot Award – by which he meant he had in fact submitted his own material for consideration."[10]

On 22 January 2014, Oliver Tickell commented on Facebook:

- "My first appearance in this Esteemed Organ. It could have been a lot worse. I should be thankful for the publicity."[11]

Suspect pursuit

Issue number 1404, published on 28 October 2015, carried the following article on page 39 entitled "Suspect pursuit" and is believed to have been authored by John Ashton:

The announcement earlier this month that the Scottish police are pursuing two new Libyan suspects over the Lockerbie bombing appeared, at first glimpse to be a vindication of the highly controversial conviction of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi: both men were associates of his. Indeed one of them, Abu Agila Mas'ud, had on at least three occasions travelled on the same flights as Megrahi – including the morning of December 21, prior to the blast on board Pan Am 103. The pair flew out of Malta, where the prosecution claimed the bomb originated.

Further evidence from a Libyan informant and the files of the former East German security service, the Stasi, suggested that Mas'ud was also the technical expert responsible for a bomb used in the La Belle disco in Berlin April 1986, two years before Lockerbie, which killed three people, including two US servicemen. Mas'ud is now in a Tripoli prison, convicted of building car bombs during Libya’s revolution. The other named suspect, Abdullah al-Senussi, appears to be in the frame for no better reason than he was the former Libyan security chief and a relative by marriage of Megrahi’s.

Perhaps embarrassingly for the police and the Crown Office, the “breakthrough” came not from them, but through the painstaking efforts of a relative of a Lockerbie victim. American Ken Dornstein, whose brother was one of the 270 who perished in the blast, made a three-part documentary "My Brother’s Bomber", recently broadcast by America’s PBS Frontline series. In fact neither name is new to the Lockerbie investigation. Senussi was named in a US State Department fact sheet that accompanied Megrahi’s indictment and Scottish police statements show that Mas'ud became a suspect in early 1991, but it was apparently decided that there was not enough evidence against him.

What Dornstein spotted was that although Megrahi had always denied knowing Mas'ud, he was seen greeting Megrahi on his return to Libya, when he was released early on compassionate grounds.

The documentary provided a strong circumstantial case against Mas'ud. But so much of any case against him must rely upon the same flawed evidence that persuaded the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission – and others before them – to conclude Megrahi may have been wrongly convicted (Eyes passim ad nauseam). That included the dodgy claim that the bomb began its journey from Malta via Frankfurt, when there was compelling evidence that it was loaded at Heathrow. Not to mention the supposed forensic evidence linking the bomb to the Libyans. New testing of a tiny fragment of circuit board, showed it was no match for timing devices known to have been bought by Libya.

Then there is a further problem: the main witness implicating Mas'ud in the German disco bombing is a Libyan Musbah Eter, who German media later found out was working for the CIA. Now, 20 years later, Eter is claiming that both Megrahi and Mas'ud are also responsible for the Lockerbie bombing. Quite why he kept quiet for so long remains a mystery. Tellingly, perhaps, the Crown Office and Scottish police have failed to follow up the new scientific evidence, preferring instead to concentrate on leads that bolster the original conviction. Hardly surprising then, that some of the bereaved families like Jim Swire, father of Flora, remain sceptical that they will ever learn the truth.[12]

Two-faced

Having read the above article, Lockerbie campaigner Patrick Haseldine accused John Ashton of being two-faced in relation to the Dornstein documentary "My Brother's Bomber":

- Ashton said "Abdullah al-Senussi appears to be in the frame for no better reason than he was the former Libyan security chief and a relative by marriage of Megrahi’s." Doesn't Ashton know that Senussi was convicted in 1999 of the bombing of UTA Flight 772 of 19 September 1989?

- Ashton told the Scottish Daily Mail on 21 September 2015 that he had actually helped make Dornstein's film as a paid consultant, saying "This is another piece of the jigsaw and that’s to be welcomed. Mas’ud appears to have been a bad guy, if what Ken has uncovered is accurate. I would welcome him being put on trial so this evidence can be tested."[13]

References

- ↑ "Private Eye hits highest circulation for more than 25 years"

- ↑ "Andrew Osmond – Obituary"

- ↑ "Richard Ingrams interview"

- ↑ "Not Private Eye"

- ↑ "Paul Foot, radical columnist and campaigner, dies at 66"

- ↑ "Private Eye and Lobster on the Pinay Circle"

- ↑ "Lockerbie - The Flight From Justice"

- ↑ "Fragment of the imagination?", Private Eye issue 1195 (page 28), 12–25 October 2007

- ↑ "Flight 103: It was the Uranium"

- ↑ "Private Eye rumbles Haselnut and The Ecologist"

- ↑ "My first appearance in this Esteemed Organ"

- ↑ "Private Eye reports on the latest Lockerbie claims"

- ↑ "Technical expert from Colonel Gaddafi's regime identified as new suspect in Lockerbie bombing by US documentary-maker whose brother died in attack"