Document:Electronic Espionage - A Memoir

Subjects: NSA, Cold War

Source: Cryptome (Link)

Author's Note

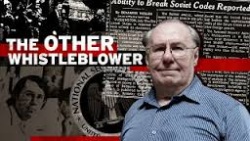

The article begins with commentary on information provided by an anonymous former analyst of the National Security Agency followed by the full interview. The analyst was later named as Perry Fellwock, but used the pseudonym 'Winslow Peck' for the interview. The Ramparts editor for the issue was David Horowitz.

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Ramparts: U.S. Electronic Espionage: A Memoir

About thirty miles northeast of CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, right off the Baltimore-Washington expressway overlooking the flat Maryland countryside, stands a large three story building known informally as the "cookie factory." It's officially known as Ft. George G. Meade, headquarters of the National Security Agency.

Three fences surround the headquarters. The inner and outer barriers are topped with barbed wire, the middle one is a five-strand electrified wire. Four gatehouses spanning the complex at regular intervals house specially-trained marine guards. Those allowed access all wear iridescent I.D. badges — green for "top secret crypto," red for "secret crypto." Even the janitors are cleared for secret codeword material. Once inside, you enter the world's longest "corridor" — 980 feet long by 560 feet wide. And all along the corridor are more marine guards, protecting the doors of key NSA offices. At 1,400,000 square feet, it is larger than CIA headquarters, 1,135,000 square feet. Only the State Department and the Pentagon, and the new headquarters planned for the FBI are more spacious. But the DIRNSA (Director, National Security Agency) can be further distinguished from the headquarters buildings of these three other giant bureaucracies — it has no windows. Another palace of paranoia? No. For DIRNSA is the command center for the largest, most sensitive and far-flung intelligence gathering apparatus in the world's history. Here, and in the nine-story Operations Building Annex, upwards of 15,000 employees work to break the military, diplomatic and commercial codes of every nation in the world, analyze the de-crypted messages, and send the results to the rest of the U.S. intelligence community.

Far less widely known than the CIA, whose Director Richard Helms will occasionally grant public interviews, NSA silently provides an estimated 80 percent of all valid U.S. intelligence. So secret, so sensitive is the NSA mission and so highly indoctrinated are its personnel, that the Agency, twenty years after its creation, remains virtually unknown to those employees outside the intelligence community. The few times its men have been involved in international incidents, NSA's name has been kept out of the papers.

Nevertheless, the first American killed in Vietnam, near what became the main NSA base at Phu Bai, was an NSA operative. And the fact that Phu Bai remains the most heavily guarded of all U.S. bases suggests that an NSA man may well be the last.

The scope of the NSA's global mission has been shrouded in secrecy since the inception of the Agency. Only the haziest outlines have been known, and then only on the basis of surmise. However, Ramparts has recently been able to conduct a series of lengthy interviews with a former NSA analyst willing to talk about his experiences. He worked for the Agency for three and a half years — in the cold war of Europe and the hot one in Southeast Asia. The story he tells of NSA's structure and history is not the whole story, but it is a significant and often chilling portion of it.

Our informant served as a senior NSA analyst in the Istanbul listening post for over two years. He was a participant in the deadly international fencing match that goes on daily with the Soviet Union, plotting their air and ground forces and penetrating their defenses. He watched the Six Day War unfold and learned of the intentions of the major powers — Israel, the Soviet Union, the United States, France, Egypt — by reading their military and diplomatic radio traffic, all of it duly intercepted, de-coded and translated by NSA on the spot. As an expert on NSA missions directed against the Soviet Union and the so-called "Forward Countries" — Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania and Yugoslavia — he briefed such visiting dignitaries as Vice President Humphrey. In Indochina he was a senior analyst, military consultant and U.S. Air Force intelligence operations director for North Vietnam, Laos, the northern-most provinces of South Vietnam and China. He is a veteran of over one hundred Airborne Radio Direction Finding missions in Indochina — making him thoroughly familiar with the "enemy" military structure and its order of battle.

With the benefit of the testimony he provides, we can see that the reason for the relative obscurity of NSA of less to do with its importance within the intelligence community than with the limits of its mission and the way it gets its results. Unlike the CIA, whose basic functions are clearly outlined in the 1947 law that created it, NSA, created in 1952, simply gathers intelligence. It does not formulate policy or carry out operations. Most of the people working for NSA are not "agents," but ordinary servicemen attached to one of three semi-autonomous military cryptologic agencies — the Air Force Security Service, the largest; the Naval Security Group; and the Army Security Agency, the oldest. But while it is true that the Agency runs no spies as in the popular myth, its systematic Signal Intelligence intercept mission is clearly prohibited by the Geneva Code. What we are dealing with is a highly bureaucratized, highly technological intelligence mission whose breadth and technological sophistication appear remarkable even in an age of imperial responsibilities and electronic wizardry.

So that not a sparrow or a government falls without NSA's instantaneous knowledge, over two thousand Agency field stations dot the five continents and the seven seas. In Vietnam, NSA's airborne flying platforms carrying out top-secret Radar Detection Finding missions, supply U.S. commanders with their most reliable information on the location of communist radio transmitters, and thus on the location of NLF units themselves. Other methods, the use of sensors and seismic detectors, either don't work or are used merely to supplement NSA's results. But the Agency's tactical mission in Indochina, intelligence support for U.S. commanders in the field, however vital to the U.S. war effort, is subsidiary in terms of men, time and material to its main strategic mission.

The following interview tells us a great deal about both sides of the NSA mission — everything from how Agency people feel about themselves and the communist "enemy" to the NSA electronic breakthroughs that threaten the Soviet-American balance of terror. We learn for example that NSA knows the call signs for every Soviet airplane, the numbers on the side of each plane, the name of the pilot in command; the precise longitude and latitude of every nuclear submarine; the whereabouts of nearly every Soviet VIP; the location of every Soviet missile base; every army division, battalion and company — its weaponry, commander and deployment. Routinely the NSA monitors all Soviet military, diplomatic and commercial radio traffic, including Soviet Air Defense, Tactical Air and KGB forces. (It was the NSA that found Che Guevara in Bolivia through radio communications intercept and analysis.) NSA cryptologic experts seek to break every Soviet code and do so with remarkable success, Soviet scrambler and computer-generated signals being nearly as vulnerable as ordinary voice and manual morse radio transmissions. Interception of Soviet radar signals enables NSA to gauge quite precisely the effectiveness of Soviet Air Defense units. Methods have even been devised to "fingerprint" every human voice used in radio transmissions and distinguish them from the voice of every other operator. The Agency's Electronic Intelligence Teams (ELINT) are capable of intercepting any electronic signal transmitted anywhere in the world and, from an analysis of the intercepted signal, identify the transmitter and physically reconstruct it. Finally, after having shown the size and sensitivity of the Agency's big ears, it is almost superfluous to point out that NSA monitors and records every trans-Atlantic telephone call.

Somehow, it is understandable, given the size of the stakes in the Cold War, that an agency like NSA would monitor U.S. citizens' trans-Atlantic phone calls. And we are hardly surprised that the U.S. violates the Geneva Code to intercept communist radio transmissions. What is surprising is that the U.S. systematically violates a treaty of its own making, the UKUSA Agreements of 1947. Under this treaty, the U.S., Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia erected a white-anglo-saxon-protestant nation communications intelligence dictatorship over the "Free World." The agreement distinguishes between three categories of intelligence consumers, First, Second, and Third Party consumers. The First Party is the U.S. intelligence community. The Second party refers to the other white anglo-saxon nations' communications intelligence agencies; i.e. Great Britain's GCHQ, Canada's CBNRC, etc. These agencies exchange information routinely. Non-WASP nations, the so-called Third Party nations, are placed on short intelligence rations. This category includes all NATO allies — West Germany, France, Italy, as well as South Vietnam, Japan, Thailand and the non-WASP allies in SEATO. But the idea of a closed club of gentlemanly white men gets quickly dispelled when we learn that the U.S. even intercepts the radio communications of its Second Party UKUSA "allies." From the U.S. military base at Chicksands, for example, and from the U.S. Embassy in London, NSA operatives busily intercept and transcribe British diplomatic traffic and send it off for further analysis to DIRNSA.

We feel that the information in this interview — while not of a "sensitive" nature — is of critical importance to America for the light it casts on the cold war and the anti-communist myths that perpetuate it. These myths about the aggressive intentions of the Soviet Union and China and about North Vietnam's "invasion of a democratic South Vietnam," can only be sustained by keeping the American people as ignorant as possible about the actual nature of these regimes and the great power relationships that exist in the world. The peace of the world, we are told, revolves shakily on a "balance of terror" between the armed might of the Soviet Union and the United States. So tenuous is this balance that if the U.S. were to let down its guard ever so slightly, if it were, for example, to reduce the ever-escalating billions allocated for "defense," we would immediately face the threat of destruction from the aggressive Soviets, who are relentless in their pursuit of military superiority. Our informant's testimony, based on years of dealing with the hard information about the Soviet military and its highly defensive-oriented deployment, is a powerful and authoritative rebuttal to this mythology.

But perhaps even an more compelling reason requires that this story be told. As we write, the devastating stepped-up bombing of North Vietnam continues. No one can say with certainty what the ultimate consequences of this desperate act are likely to be. Millions of Americans, perhaps a majority, deplore this escalation. But it would be a mistake to ignore the other millions, those who have grown up in fear of an entity known as "world communism." For them Nixon's latest measures have a clear rationale and a plausible purpose. It is precisely this political rationale and this strategic purpose that the testimony of our informant destroys.

We are told by Nixon that South Vietnam has been "invaded" by the North which is trying to impose its will on the people of the South. This latest version of why we continue to fight in Indochina — the first version stressed the threat of China which allegedly controlled Hanoi, even as Moscow at one time was thought to control Peking — emphasizes Hanoi's control over the NLF. Our evidence shows that the intelligence community, including NSA, has long determined that the NLF and the DRV are autonomous, independent entities. Even in Military Region I, the northern-most province of South Vietnam, and the key region in the "North Vietnamese" offensive, the command center has always been located not in Hanoi but in somewhere in the Ia Drang valley. This command center, the originating point for all military operations in the region, is politically and militarily under the control of the PRG. Known as Military Region Tri Tin Hue (MRTTH) it integrates both DRV and NLF units under the command. Hanoi has never simply "called the shots," although the DRV and PRG obviously have common reasons for fighting and share common objectives. All of this information NSA has passed on systematically to the political authorities who, equally systematically, have ignored it.

Nixon's military objective — halting supplies to the South through bombing and mining of North Vietnamese ports — turns out to be as bogus as his political rationale. Military supplies for the DRV and the NLF are stored along the Ho Chi Minh trail in gigantic underground staging areas know as bamtrams. These are capable of storing supplies for as long as twelve months, at normal levels of hostilities, according to NSA estimates.Even at the highly accelerated pace of the recent offensive, it would take several months (assuming 100 percent effectiveness) before our bombing and mining wold have any impact on the fighting.

Taken together, the experience of our informant in Europe, in the Middle East, and in Indochina bears witness to the aggressive posture of the United States in the late 1960s. It is hard to see anything defensive about it. Our policy makers are well-informed by the intelligence community of the defensive nature of our antagonists' military operations. The NSA operations here described reflect the drive of a nation to control as much of the world as possible, whose leaders trust no one and are forced to spy on their closet allies in violation of the treaties they initiated themselves; leaders, moreover, for whom all nations are, in the intelligence idiom, "targets," and who maintain the U.S. imperium around the world in large part through threat of actual physical annihilation.

At home, however, the favored weapon employed is ignorance rather than fear. Like NSA headquarters itself, the United States is surrounded by barriers — barriers of ignorance that keep its citizens prisoners of the cold war. The first obstacle is formed by the myths propagated about communism and about its aggressive designs on America. The second, and dependent for its rationale on the first, is the incredible barrier of governmental secrecy that keeps most of the questionable U.S. aggressive activities hidden nor from our "enemies," who are the knowledgeable victims, but from the American people themselves. The final barrier is perhaps the highest and is barbe with the sharpest obstacles of all. It is nothing less than our reluctance as Americans to confront what we are doing to the peoples of the world, ourselves included, by organizations like the National Security Agency.

Q. Let's begin by getting a sense of the National Security Agency and the scope of its operations.

A. O.K. At the broadest level, NSA is a part of the United States intelligence community and a member of the USIB, the United States Intelligence Board. It sits on the Board with the CIA, the FBI, the State Department's RCI, and various military intelligence bureaus. Other agencies also have minor intelligence-gathering units, even the Department of the Interior.

All intelligence agencies are tasked with producing a particular product. NSA produces — that is, collects, analyzes, and disseminates to its consumers — Signals Intelligence, called SIGINT. It comes from communications or other types of signals intercepted from what we called "targeted entities," and it amounts to about 80 percent of the viable intelligence the U.S. government receives. There is COMSEC, a secondary mission. This is to produce all the communications security equipment, codes and enciphering equipment for the United States and its allies. This function of the NSA involves the monitoring of our own communications to make sure they are secure. But SIGINT is the main responsibility.

As far as NSA's personnel is concerned, they are divided into two groups: those that are totally civilian, and those like me who derived from the military. As far as the collection of data is concerned, the military provides almost all the people. They are recruited through one of the service cryptologic agencies. The three agencies are the U.S. Air Force Security Service (USAFSS), the Army Security Agency (ASA), and the Navy Security Group (NSG). These agencies may control a few intelligence functions that are primarily tactical in nature and directly related to ongoing military operations. But generally, DIRNSA, the Director of the National Security Agency, is completely in control over all NSA's tasks, missions and people.

The NSA, through its sites all over the world, copies — that is, collects — intelligence from almost every conceivable source. That means every radio transmission that is of a strategic or tactical nature, or is related to some government, or has some political significance. NSA is powerful, and it has grown since its beginning back in 1947. The only problem it has had has come over the last few years. Originally it had equal power with the CIA on the USIB and the National Security Council. But recently the CIA has gained more of a hegemony in intelligence operations, especially since Richard Helms became director of the entire intelligence community.

Q. Does the NSA have agents in the field?

A. Yes, but probably not in the way you mean. It is different from other intelligence agencies in that it's not a consumer of its own intelligence. That is, it doesn't act on the data it gathers. It just passes it on. Generally, there's a misconception all Americans have about spying. They think it's all cloak and dagger, with hundreds of James Bonds wandering around the world in Aston-Martins, shooting people. It just doesn't happen. It's all either routine or electronic. I got to know a lot of CIA people in my three and a half years with NSA, and it became pretty clear to me that most of them sit around doing mundane stuff. You know, reading magazines, newspapers, technical journals. Like some people say, they do a lot of translating of foreign phone books. Of course I did meet a few who were out in the jungles with guns in their hands too.

But as far as the NSA is concerned, it is completely technological. Like I said, at least 80 percent of all viable intelligence that this country receives and acts on comes from the NSA, and it is all from signals intelligence, strategic and tactical. I saw it from both angles — first strategic in working against the Soviet Union in Turkey and then tactical flying missions against the VC in Nam. Information gathering by NSA is complete. It covers what foreign governments are doing, planning to do, have done in the past: what armies are moving where and against whom; what air forces are moving where, and what heir capabilities are. There really aren't any limits on NSA. Its mission goes all the way from calling in the B-52s in Vietnam to monitoring every aspect of the Soviet space program.

Q. In practical terms, what sort of data are collected by NSA?

A. Before going into that, I should get into the types of signals NSA collects. There are three basic area. First is what we called ELINT, electronics intelligence. This involves the interception and analysis of any electronics signal. There isn't necessarily any message on that signal. It's just the signal, and it's mainly used by technicians. The only time I ever remember using ELINT was when we were tracking a Russian fighter. Some of them has a particular type of radar system. As I remember, we called this system MANDRAKE. Anyhow, every time this system signalled, a particular type of electronic emission would occur. Our ELINT people would be looking for it, and whenever it came up, it would let them positively identify this type of fighter.

The second type of signal is related to this. It is intelligence from radar, called RADINT. This also involves the technicians. Let me give you an example. There is a particular type of Soviet radar system known in NSA by a code name which we'll call SWAMP. SWAMP is used by the Soviet technical air forces, by their air defense, by the KGB and some civilian forces. It is their way of locating any flying entity while it is in the air. It had a visual read-out display, so that, whenever a radar technician in the Soviet Union wanted to plot something on his map, he could do it by shooting a beam of light on a scope and then send it to whoever wanted to find out information about that airplane. Our RADINT people intercepted SWAMP signals in our European listening posts. From the data they got, NSA analysts were able to go back to the headquarters at Fort meade and in less than eight weeks completely reconstruct SWAMP. We duplicated it. This meant that we were able to see exactly what the Soviet operators were seeing when they used SWAMP. So, as far as this radar was concerned, the upshot was that they were doing our tracking for us. We knew everything they knew, and we knew what they were able to track over their airspace, and what they weren't.

Q. Does this mean that we can jam their radar?

A. Yes, part of the function of ELINT and RADINT is to develop electronic counter measures. There's a counter measure for every type of Soviet radar.

Q. You said there were three areas. You've gone over ELINT and RADINT. What's the third?

A. This is by far the most important. It's communications intelligence. COMINT. It involves the collection of radio communications of a targeted entity. NSA intercepts them, reproduces them in its equipment and breaks down any code used to encipher the signal. I should say that what I call a "targeted entity" could mean any country — NSA gathers data on them all — but in practical terms it's almost synonymous with the Soviet Union.

COMINT is the important function. It's what I was in, and it represents probably 95 percent of relevant SIGINT intelligence. As a matter of fact, the entire intelligence community is also known as the COMINT community.

Q. It would probably be good to backpedal for a moment before we go into your experiences in NSA and get into the way you joined the organization.

A. Well, I'd been in college, was bored, and wanted to do something different. I come from the Midwest, and we still believed those ads about joining the military and seeing the world. I enlisted in the Air Force. Like everybody else, I was shocked by basic training, but after that, when it came time to choose what I'd be doing for the rest of my time, it wasn't too bad. I tried for linguist's training, but there weren't any openings in the schools. I was then approached by three people I later found were a part of the National Security Agency. They interviewed me along with four other guys and asked us if we'd like to do intelligence work. We took a battery of tests, I.Q. and achievement tests, and had some interviews to determine our political and emotional stability. They really didn't go into our politics very much, I guess because were all so obviously apathetic. Their main concern was our sex life. They wanted to know if we were homosexual.

At this point, it was 1966, I suppose I had what you would call an analysis of the world situation. But it was primarily based on a belief in maintaining the balance of power. I really didn't see anything wrong with what our government was doing. Also, the few hints about what we might be doing in NSA were pretty exciting: world-wide travel working in the glamorous field of intelligence, being able to wear civilian clothes.

After getting admitted, I was bussed to Goodfellow Air Force Base at San Angelo, Texas. Originally, it was a WAC base or something like that, but now it's entirely an intelligence school for NSA. The whole basis of the training was their attempt to make us feel we were the absolute cream of the military. For most GIs, the first days in the military are awful, but as soon as we arrived at the school we were given a pass to go anywhere we wanted, just as long as were were back in school each morning. We could live off base; there was no hierarchical thing inside the classroom.

Q. What sort of things did you focus on in school?

A. At first it was basic stuff. For about two months we just learned primary analysis techniques, intelligence terms, and a rough schematic of the intelligence community. We learned a few rudimentary things about breaking codes and intercepting messages. A lot of people were dropped out of the program at this time because of inadequate school performance, poor attitude, or because of something in their backgrounds didn't prove out. Actually, of fifteen people with me in this class, only four made it through. We had been given access only to information rated "confidential" all the time, but then we got clearance and a Top Secret cryptologic rating.

The first day of the second phase of school began when we walked into the classroom and saw this giant map on the wall. It was marked "Top Secret," and it was of the Soviet Union. For the next three months, we learned about types of communications in operations throughout the world and also in-depth things about the political and administrative makeup of various countries. The Soviet Union, of course, was our primary focus. And we learned every one of its military functions: the entire bureaucratic structure, including who's who and where departments and headquarters are located; and a long history of its military and political involvements, especially with countries like China and the East European bloc, which we called "the forward area."

We learned in-depth analysis — how to perform different types of traffic analysis, cryptic analysis, strategic analysis. A lot of the texts we used were from the Soviet Union, and had been translated by the CIA.

I'm not especially proud of it now, but I should tell you that I graduated at the head of the class. We had a little ceremony inside a local movie theater. I was called up with two guys from other classes and given special achievement certificates. We were given our choice of assignments anywhere in the world. I chose Istanbul. It seemed like the most far-out and exotic place available. After that I left San Angelo and went to Monterey to the Army's language school for a month and a half. I learned a bit of very technical Russian — basically how to recognize the language — and then to Fort Meade NSA headquarters for a couple of weeks indoctrination about Istanbul, our operation there at Karmasel, and the whole European intelligence community.

Q. When did you get to Istanbul?

A. That was January 1967.

Q. What did you do there?

A. I was assigned to be one of the flight analysts working primarily against the Soviet tactical Air Forces and Soviet long range Air Forces. I had about twenty-five morse operators who were listening to morse signals for me, and about five non-morse and voice operators. It was a pretty boring job for them. A morse operator, for instance, just sits there in front of a radio receiver with headphones, and a typewriter for copying morse signals. They would "roll onto" their target, which means that they would go to the frequency that their target was using. The list of likely frequencies and locations and the call signals that would be used — all this information was made available by the analyst as technical support to the operator. In return the operator would feed the copy to me: I'd perform analysis on it and correlate with other intelligence collected there in Istanbul, and at the NSA installations in the rest of Europe.

Q. Where were the other NSA installations in Europe?

A. The major ones aside from Karmasel are in Berlinhof and Darmstadt, West Germany; Chicksands, England; Brindisi, Italy; and also at Trabesan and Crete. Some of these sites have gigantic Feranine antennas. This is a circular antenna array, several football fields in diameter, and it's capable of picking up signals from 360 degrees. They're very sensitive. We can pick up hundreds of signals simultaneously. We pick up voices speaking over short-range radio communications thousands of miles away.

The whole Air Force part of NSA, the USAFSS units, is known as the European Security region. It is headquartered at the I.G. Farben building in Berlin. The Army ASA has units attached to every Army installation in Europe. The Naval NSG has its sites aboard carriers in the 6th Fleet. But mainly it was us.

Q. What does this apparatus actually try to do?

A. Like I said, it copies — that is, intercepts for decoding and analysis — communications from every targeted country. As far as the Soviet Union is concerned, we know the whereabouts at any given time of all its aircraft, exclusive of small private planes, and its naval forces, including its missile-firing submarines. The fact is that we're able to break every code they've got, understand every type of communications equipment and enciphering device they've got. We know where their submarines are, what every one of their VIPs is doing, and generally their capabilities and the dispositions of all their forces. This information is constantly computer correlated, updated, and the operations go on twenty-four hours a day.

Q. Let's break it down a little. How about starting with the aircraft. How does NSA keep track of the Soviet air forces?

A. First, by copying Soviet Navair, which is their equivalent of the system our military has for keeping track of its own planes. And their Civair, like our civilian airports: we copy all of their air controllers' messages. So we have their planes under control. Then we copy their radar plotting of their own air defense radar, which is concerned with flights that come near their airspace and violate it. By this I mean the U.S. planes that are constantly overflying their territory. Anyhow, all this data would be correlated with our own radar and with the air-to-ground traffic these planes transmitted and our operators picked up. We were able to locate them exactly even if they weren't on our radar through RDF — radio direction finding. We did this by instantaneously triangulating reception coming through these gigantic antennas I mentioned. As far as Soviet aircraft are concerned, we not only know where they are: we know what their call signs are, what numbers are on the side of every one of their planes, and, most of the time, even which pilots are flying which plane.

Q. You said that we overfly Soviet territory?

A. Routinely as a matter of fact — over the Black Sea, down to the Baltic. Our Strategic Air Force flies the planes, and we support them. By that I mean that we watch them penetrate the Soviet airspace and then analyze the Soviet reaction — how everything from their air defense and tactical air force to the KGB reacts. It used to be that SAC flew B-52s. As a matter of fact one of them crashed in the Trans-Caucasus area in 1968 and all the Americans on board were lost.

Q. Was it shot down?

A. That was never clear, but I don't believe so. The Soviets know what the missions of the SAC planes are. A lot of times they scramble up in their jets and fly wing-to-wing with our planes. I've seen pictures of that. Their pilots even communicate with ours. We've copied that.

Q. Do we still use U-2s for reconnaissance?

A. No, and SAC doesn't fly the B-52s anymore either. Now the plane they use is the SR-71. It has unbelievable speed and it can climb high enough to reach the edge of outer space. The first time I came across the SR-71 was when I was reading a report of Chinese reaction to its penetration of their airspace. The report said their air defense tracking had located the SR-71 flying at a fairly constant pattern at a fairly reasonable altitude. They scrambled MIG-21s on it, and when they approached it, the radar pattern indicated that the SR-71 had just accelerated with incredible speed and rose to such a height that the MIG-21s just flew around looking at each other. Their air-to-ground communications indicated that the plane just disappeared in front of their eyes.

I might tell you this as a sort of footnote to your mentioning of the U-2. The intelligence community is filled with rumor. When I got to Turkey, I immediately ran into rumors that Gary Powers' plane had been sabotaged, not shot down. Once I asked someone who'd been in Istanbul for quite a while and he told me that it was reported in a unit history that this had happened. The history said it had been three Turks working for the Soviets and that they'd put a bomb on the plane. I didn't read this history myself, however.

Q. You have explained how we are able to monitor Soviet air traffic to the extent indicated, but it's hard to believe that we could know where all their missile submarines are at any given moment.

A. Maybe so, but that's the way it is. There are some basic ways in which we can keep track of them, for example through the interpretation of their sub-to-base signals which they encode and transmit in bursts that last a fraction of a second. First we record it on giant tape drops several feet apart, where it is played back slowly so that we get the signal clearly. Then the signal will be modulated — that is, broken down so we can understand it. Then the codes are broken and we get the message, which often turns out to contain information allowing us to tell where they are.

Another way in which we keep track of these subs is much simpler. Often they'll surface someplace and send a weather message.

Q. But don't submarines go for long periods without communicating, maneuvering according to some pre-arranged schedule?

A. Actually, not very often. There are times during a war exercise or communications exercise when they might not transmit for a week or even longer. But we still keep track of them. We've discovered that they're like all Soviet ships in that they travel in patterns. By performing a very complicated, computerized pattern analysis, we are able to know where to look for a particular ship if it doesn't turn up for a while. The idea is that they revert from that pattern only in extreme emergency situation: but during such a situation they'll have to be in communication at least once. We know how many subs they have. And in practical terms, when one of them is not located, NSA units tasked with submarine detection concentrate all their energies on finding it.

Q. How do you know this? Did you ever have responsibility for submarine detection?

A. No. My information comes from two sources. First, the fact that there were analysts sitting right next to me in Karmasel who were tasked on subs. Second, I read what we called TEXTA. TEXTA means "technical extracts of traffic." It is a computer-generated digest of intelligence collected from every communications facility in the world — how they communicate, what they transmit, and who to. It is the Bible of the SIGINT community. It is constantly updated, and one of an analyst's duties is reading it. You've got to understand that even though each analyst had his own area to handle, he also had to be familiar with other problems. Quite often I would get through my operators base-to-base submarine traffic and I'd have to be able to identify it.

Q. The implications of what you're saying are very serious. In effect, it means that based on your knowledge there is no real "balance of terror" in the world. Theoretically, if we know where every Soviet missile installation, military aircraft and missile submarine is at every moment, we are much closer than anyone realized to a first-strike capacity that would cripple their ability to respond.

A. Check.

Q. How many NSA people were there at Istanbul and in the rest of the installations in Europe?

A. About three thousand in our operation. It would be hard to even guess how many in the rest of Europe.

Q. What were the priorities for gathering information on Soviet operations?

A. First of all, NSA is interested in their long-range bombing forces. This includes their rocket forces, but mainly targets on their long-range bombers. This is because the feeling is that, if there is conflict between us and them, the bombers will be used first, as a way of taking a step short of all-out war. Second, and very close to the bombing capabilities, is the location of their missile submarines. Next would be tasking generated against the Soviet scrambler, which is their way of communicating for all of their services and facilities. After this would be their Cosmos program. After that things like tasking their KGB, their air controllers, their shipping, and all the rest of the things tend to be on the same priority.

Q. All this time, the Soviets must be doing intelligence against us too. What is its scope?

A. Actually, they don't get that much. They aren't able to break our advanced computer generated scrambler system, which accounts for most of the information we transmit. They do a lot of work to determine what our radar is like, and they try to find out things by working on some of the lower level codes used by countries like Germany and the Scandinavian countries we deal with. Their SIGINT operation is run by the KGB.

The key to it is that we have a ring of bases around them. They try to make up for the lack of bases by using trawlers for gathering data, but it's not the same. They're on the defensive.

Q. What do you mean by that?

A. That they're on the defensive? Well, one of the things you discover pretty early is that the whole thing of containing the communist menace for expansion is nonsense. The entire Soviet outlook of their military and their intelligence was totally different from ours. They were totally geared up for defense and to meet some kind of attack. Other than strategic capacities relating to the ultimate nuclear balance, their air capabilities are solidly built around defending themselves from penetration. They've set up the "forward" area — our term for the so-called bloc countries of eastern Europe — less as a launching pad into Europe than as a buffer zone. The only Soviet forces there are air defense forces, security forces. Put it this way: their whole technology is not of an offensive nature, simply, don't have the kind of potential for a tactical offensive that we do. They have no attack carriers, for instance. Soviet ships are primarily oriented toward protection of their coasts. Actually they do have carriers of a sort, but they are helicopter anti-submarine carriers. Another thing: they have a lot of fighters, but hardly any fighter-bombers. They do have a large submarine force, but given the fact that they are completely ringed by the U.S., this too is really of a strategic nature.

Everything we did in Turkey was in direct support of some kind of military operation, usually something clandestine like overflights, infiltrations, penetrations. If all we were interested in was what they call an "invulnerable deterrent," we could easily get our intelligence via satellite. We don't need to have these gigantic sites in Europe and Asia for this.

Q. You mentioned a few minutes ago that one of NSA's main targets was the Soviet space program. What sort of material were you interested in?

A. Everything. Obviously, one of the things we wanted to know was how close they were to getting a space station up. But w knew everything that went on in their Cosmos program. For instance, before I had gotten to Turkey, one of their rockets had exploded on the launching pad and two of their cosmonauts were killed. One died while I was there too. It was Soyuz, I believe. He developed re-entry problems on his way back from orbit. They couldn't get the chute that slowed his craft down in re-entry to work. They knew what the problem was for about two hours before he died, and were fighting to correct it. It was all in Russian, of course, but we taped it and listened to it a couple of times afterward. Kosygin called him personally. They had a video-phone conversation. Kosygin was crying. He told him he was hero and that he made a great achievement in Russian history, and that they were proud and he'd be remembered. The guy's wife got on too. They talked for a while. He told her how to handle their affairs, and what to do with the kids. It was pretty awful. Towards the last few minutes, he began falling apart, saying, "I don't want to die, you've got to do something." Then there was just a scream as he died. I guess he was incinerated. The strange thing was that we were all pretty bummed out by the whole thing. In a lot of ways, having the sort of job we did humanizes the Russians. You study them so much and listen to them for so many hours that pretty soon you come to feel that you know more about them than your own people.

Q. While you were monitoring the Soviet Union what sort of intelligence would have been considered but very important or serious?

A. In a way you do this almost routinely. That is, there are certain times that the activities of the targeted the entity are of such an important nature that a special type has to be sent out. It is called a CRITIC. This is sent around the world to a communications network called CRITICOM. The people in this network, besides NSA, are those in other intelligence or diplomatic capacities who might come across the intelligence of such importance themselves that the president of the United States would need to be immediately notified. When a CRITIC goes out, one analyst working alone can't do it can't do it. There is just too great a volume of material to correlate.

Q. What would be an example of something sent out as a CRITIC?

A. Well, one of the strangest I ever read was sent out by our base at Crete. One of the analyst traced a Soviet bomber that landed in the middle of Lake Baikal. He knew it hadn't crashed from the type of communications he monitored, and he thought they had developed a new generation of bombers able to land on water. It turned out to be a bad mistake because he neglected to remember that about three-fourths of the year this lake is completely frozen over.

But actually this sort of thing is rare. Most CRITICs are based on good reasoning and data. You work around the clock, sometimes for 30 hours at a stretch putting things together. These are the times that the job stops being routine. I guess that's why they have a say about the work in NSA: "Hours of boredom and seconds of terror."

Q. Did you ever issue a CRITIC.

A. Yes, several. During Czechoslovakia, for instance, when it became clear the Soviets were moving their troops up. We also issued a number of CRITICs during the Mideast war of 1967.

Q. Why?

A. Well, I was part of an analysis team that was predicting the war at least two months before it began. I guess we issued our first CRITIC on this in April. We did it on the basis of two sources. One, we and the Crete station had both been picking up data as early as February that the Israelis had a massive build-up of arms, a massing of men and materiel, war exercises, increased level of Arab territory — just everything a country does to prepare for war. Two, there were indications that the Soviets were convinced there was going to be a war. We know this from the traffic we had on diplomatic briefings sent down from Moscow to a commanding general of a particular region. And by April they had sent their VTA airborne, their version of Special Forces paratroopers, to Bulgaria. Normally they're based in the Trans-Caucasus, and we knew from their contingency plans that Bulgaria was a launching point for the Middle East. Because some of these forces were being given to cram-courses in Israeli and Arabic languages.

Q. All this leaves the sequence of events that immediately preceded the Six Day War — the various countercharges, the U.N. pullout, the closing of the Straits — still pretty obscure. Did NSA evidence clear this up?

A. No. Not really. But one of the things that confused us at first was the fact that until last days before the war the Arabs weren't doing anything to prepare. They weren't being trained to scramble their air force. This is why there was a total chaos when the Israelis struck.

Q. How did the White House react to your reports about all this?

A. Well, in every message we sent out, we always put in our comments at the end — there's a place for this in the report form — and they'd say something like "Believe there is some preparation for an expected Israeli attack . Request your comments." They didn't exactly ignore it. They'd send back, "Believe this deserves further analysis," which means something like, "We don't really believe you, but keep sending us information." Actually, we all got special citations when the whole thing was over.

Q. Why didn't they believe you?

A. I suppose because the Israelis were assuring them that they were not going to attack and Johnson was buying it.

Q. You remember about the "Liberty," the communications ship we sent in along the coast which was torpedoed by Israeli gunboats? The official word at the time was that the whole thing was a mistake. Johnson calls it a "heartbreaking episode" in The Vantage Point. How does this square with your information?

A. The whole idea of sending the "Liberty" in was that at that point the U.S. simply didn't know what was going on going on. We sent it in close so that we could find out hard information about what the Israelis' intentions were. What it found out, among other things, was that Dayan's intentions were to push on to Damascus and to Cairo. The Israelis shot at the "Liberty," damaged it pretty badly and killed some of the crew, and told it to stay away. After this it got very tense. It became pretty clear that the White House had gotten caught with its pants down.

Q. What were the Russians doing?

A. The VTA airborne was loaded into planes. They took off from Bulgaria and their intention was clearly to make a troop drop on Israel. At this point became pretty clear that we were approaching a situation where World War III could get touched off at any time. Johnson got on the hot line and told them we were headed for a conflict if they didn't on those planes around. They did.

Q. Was it just these airborne units that were on the move?

A. No. There was all kinds of other action too. Some of their naval forces had started to move, and there was increased activity in their long-range bombers.

Q. What about this idea that Dayan had decided to push on to the cities you mentioned. What happened there?

A. He was called back, partly because of U.S. pressure, partly by people in the Israeli political infrastructure. he was somewhat chastened and never given back total control of the Army.

Q. How do you know this?

A. Like I said earlier, NSA monitors every government. This includes Tel Aviv. All the diplomatic signals from the capital to the front and back again were intercepted. Also at this same time we were copying the French, who were very much involved on both sides playing a sort of diplomatic good offices between Cairo and Tel Aviv. As far as Dayan is concerned, the information came from informal notes from analysts at Crete who were closer to the situation than we were. Analysts send these informal notes from one station to another to keep each other informed about what is happening. One of the notes I got from Crete said Dayan had been called back from the field and reprimanded. Obviously, by this time the Israelis were getting heat from the U.S.

Q. What did the Russians do after the situation cooled down a bit?

A. Immediately after the war — well, not even afterwards, but towards the end — they began the most massive airlift in the history of the world to Cairo and Damascus. Supplies, food, and some medical equipment, but mostly arms and planes. They sent in MIG-21s fully assembled, fueled, and ready to fly in the bellies of their big 101-10s. At landing the doors would open, and the MIGs would roll out, ready to go. Also there was quite a bit of political maneuvering inside the Soviet Union right afterwards. I don't quite remember the details, but it was mainly in the military, not in the Politbureau.

Q. We routinely monitor the communications of allies like Israel?

A. Of course.

Q. What other sorts of things do we learn?

A. Practically everything. For instance, we know that the Israelis were preparing nuclear weapons at their development site at Dimona. Once the U.S. Ambassador to Israel visited there. They had been calling it a textile plant as a cover, and when he went there they presented him with a new suit. It was a charade, you know. They didn't have warheads deployed then, but they were close to it. I'm sure they must have a delivery system in operation b now. It was said that American scientific advisors were helping them in this development. I mean it was said on the intelligence grapevine. I didn't know it for a fact. But this grapevine is usually fairly accurate.

Q. All the material you've been discussing is classified?

A. Almost all of it.

Q. Who classified it?

A. I did. Analysts in NSA did. In the Agency, the lowest classification is CONFIDENTIAL. Anything not otherwise classified is CONFIDENTIAL. But SIGINT data is super-classified, meaning that only those in the SIGINT community have access to it, and then only on a "need-to-know" basis. A lot of the stuff I'd work with was SECRET and TOP SECRET, which is the highest classification of all. But after a while it occurred to me that we classified our stuff only partly because of the enemy. It seemed like they were almost as interested in keeping things from the American public as the Soviets. Hell, I'd give top secret classifications to weather reports we intercepted from Soviet subs. Certainly the Soviets knew that data. I remember when I was in school back at San Angelo one of the instructors gave us a big lecture about classifying material and he said that it was necessary because it would only confuse the American people to be let in on this data. He used those exact words. As a matter of fact, I used those words when I was training the people who worked under me.

Q. How did you relate to our allies in intelligence matters?

A. I'll have to digress a moment to answer that. The SIGINT community was defined by a TOP SECRET treaty signed in 1947. It was called the UKUSA treaty. The National Security Agency signed for the U.S. and became what's called First Party to the Treaty. Great Britain's GCHQ signed for them, the CBNRC for Canada, and DSD for Australia. New Zealand. They're all called Second parties. In addition, several countries have signed on — ranging from West Germany to Japan — over the years as Third parties. Among the First and Second Parties there is supposed to be a general agreement not to restrict data. Of course it doesn't work out this way in practice. The Third party countries receive absolutely no material from us, while we get anything they have, although generally it's of pretty low quality. We also worked with so-called neutrals who weren't parties to the UKUSA treat. They'd sell us everything they could collect over radar on their Russian border.

As it works out, the treaty is a one-way street. We violate it even with our Second party allies by monitoring their communications constantly.

Q. Do they know this?

A. Probably. In part, we're allowed to do it for COMSEC purposes under NATO. COMSEC, that's communications security. There's supposed to be a random checking of security procedures. But I know we also monitor their diplomatic stuff constantly. In England, for instance, our Chicksands installation monitors all their communications, and the NSA unit in our embassy in London monitors the lower-level stuff from Whitehall. Again, technology is the key. These allies can't maintain security even if they want to. They're all working with machines we gave them. There's no chance for them to be on par with us technologically.

There's the illusion of cooperation, though. We used to go to Frankfurt occasionally for briefings. The headquarters of NSA Europe, the European Security region, and several other departments in the SIGINT community are located there, inside the I.G. Farben building. We'd run into people from GCHQ there, and from the other countries. It was all fairly cordial. As a matter of fact, I got to respect the English analysts very highly. They're real professionals in GCHQ, and some are master analysts. They'll stay on the job for twenty-five or thirty years and learn a lot. The CGG is also located in the I.G. Farben building. That's the West German COMINT agency. Most of them are ex-Nazis. We used to harass them by sieg heil-ing them whenever we say them.

Once I briefed Hubert Humphrey at the I.G. Farben building. It was in 1967, when he was vice-president. The briefing concerned the Soviet tactical air force and what was capable of doing. It was all quite routine. He asked a couple of pretty dumb questions, that showed he didn't have the foggiest notion of what NSA was and what it did.

Q. But you said that you often sent reports directly to the White House.

A. yes, I did. But the material that goes there is cleaned of any reference as to where the intelligence comes from. Every morning the President gets a daily intelligence summary complied by the CIA. This information will probably contain a good deal from the NSA in it, but it won't say where it came from and the means used to collect it. That's how a man like the vice-president could be totally ignorant of the way intelligence is generated.

Q. So far we've been talking about various kinds of sophisticated electronic intelligence gathering. What about tapping of ground communications?

A. I'm not sure on the extent of this, but I know that the NSA mission in the Moscow embassy has done some tapping there. Of course all trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific telephone calls to or from the U.S. are tapped.

Every conversation, personal, commercial, whatever, is automatically intercepted and recorded on tapes. Most of them no one ever listens to, and after being held available for a few weeks, are erased. They'll run a random sort through all the tapes, listening to a certain number to determine if there is anything in them of interest to our government worth holding on to and transcribing. Also, certain telephone conversations are routinely listened to as soon as possible. These will be the ones that are made by people doing an inordinate amount of calling overseas, or are otherwise tapped for special interest.

Q. What about Africa? Does the NSA have installations there?

A. Yes, one in Ethiopia on the East Coast and in Morocco on the West Coast. These cover northern Africa, parts of the Mediterranean, and parts of the Mideast.

Q. Do they ever gather intelligence on African insurgents?

A. I went to Africa once for a vacation. I understood that there were DSUs, that's direct support units, working against Mozambique, Tanzania, Angola, those countries. These DSUs are in naval units off the coast. They are tasked with two problems: first, they copy the indigenous Portuguese forces; and second, they copy the liberation forces.

Q. Is the information used in any way against the guerrillas?

A. I don't know for sure. But I'd be surprised if it wasn't. There is information being gathered. This intelligence is fed back to NSA-Europe, of course. It has no strategic value to us, so it's passed on to NATO — one of our consumers. Portugal is part of NATO, so it gets the information. I know that U.S. naval units were DF-ing the liberation forces. That's direction finding. The way it worked was that the ship would get a signal, people on board would analyze it so see if it came from the guerrillas, say, in Angola. then they'd correlate with our installation in Ethiopia, which had also intercepted it, and pinpoint the source.

Q. Did you ever have any doubts about what you were doing?

A. Not really, not at this time. It was a good job. I was just 21 years old; I had a lot of operators working under me; I got to travel a lot — to Frankfurt, for instance, at least twice a month for briefings. I was considered to be a sort of whiz kid, and had been since I'd been in school back in San Angelo. I guess you could say that I had internalized all the stuff about being a member of the elite that they had given us. I was advancing very rapidly, partly because of a runover in personnel that happened to hit at the time I came to Turkey, and partly because I like what I was doing and worked like crazy and always took more than other analysts. But, like I said earlier, I had developed a different attitude toward the Soviet Union. I didn't see them as an enemy or anything like that. Everyone I worked with felt pretty much the same. We were both protagonists in a big game — that's the view we had. We felt very superior to CIA people we'd occasionally come in contact with. We had a lot of friction with them, and we guarded our information form them very carefully.

Q. Was there a lot of what you'd call esprit de corps among the NSA people there.

A. In some ways, yes; in other ways, no. Yes, in the sense that there were a lot who were like me — eating, drinking, sleeping NSA. The very fact that you have the highest security clearance there makes you think a certain way. You're set off from the rest of humanity. Like one of the rules was — and this was first set out when we were back at San Angelo — that we couldn't have drugs like sodium pentothol used on us in medical emergencies, at least not in the way they're used on most people. You know, truth-type drugs. I remember once one of our analysts cracked up his car in Turkey and banged himself up pretty good. He was semi-conscious and in the hospital. They had one doctor and one nurse, both with security clearances, who tended to him. And one of us was always in the room with him to make sure that while he was delirious he didn't talk too loud. Let me say again that all the material you deal with, the codes words and all, becomes part of you. I'd find myself dreaming in code. And to this day when I hear certain TOP SECRET code words something in me snaps.

But in spite of all this, there's a lot of corruption too. Quite a few people in NSA are into illegal activities of one kind or another. It's taken to be one of the fringe benefits of the job. You know, enhancing your pocketbook. Practically everybody is into some kind of smuggling. I didn't see any heroin dealings or anything like that, like I later saw among CIA people when I got to Nam, but most of us, me included, did some kind of smuggling on the side. Everything form small-time black marketeering of cigarettes or currency all the way up to transportation of vehicles, refrigerators, that sort of thing. One time in Europe I knew of a couple of people inside NSA who were stationed in Frankfurt and got involved in the white slave trade. Can you believe that? They were transporting women who'd been kidnapped from Europe to Mideast sheikdoms aboard security airplanes. It was perfect for any kind of activity of that kind. There's no customs or anything like that for NSA people. Myself, I was involved in the transportation of money. A lot of us would pool our cash, buy up various restricted currencies on our travels, and then exchange it at a favorable rate. I'd make a couple of thousand dollars each time. It was a lark. My base pay was $600 a month, and looking back I figure that I made at least double that by what you'd call manipulating currency. It sounds pretty gross, I know, but the feeling was, "What the hell, nobody's getting hurt." It's hard for me to relate to the whole thing now. Looking back, it's like that was another person doing those things and feeling those feelings.

Q. All this sounds like a pretty good deal — the job, what you call the fringe benefits, and all that. Why did you go to Vietnam?

A. Well, I'd been in Istanbul for over two years, that's one thing. And second, well, Vietnam was the big thing that was happening. I wasn't for the war, exactly, but I wasn't against it either. A lot of people in Europe were going there, and I wanted to go see what was happening. It doesn't sound like much of a reason now, but that was it.

Q. You volunteered?

A. Right. For Vietnam and for flying. They turned me down for both.

Q. Why?

A. Because of my classification. What I knew was too delicate to have me wandering around in a war zone. If I got captured, I'd know too much. That sort of thing. But I pulled some strings. I'd made what you'd call high-ranking friends, you know. Finally, I got to go. First I had a long vacation — went to Paris for a while and that sort of thing. Then I was sent back to the U.S. for schooling.

Q. What sort of schooling?

A. It was in Texas, near Brownsville. I learned a little Vietnamese and a lot about ARDF — that's airborne radio direction finding. It was totally different from what I'd been doing. It was totally practical. No more strategic stuff, just practical analysis. I had to shift my whole way of thinking around. I was going to be in these big EC-47s — airborne platforms they were called — locating the enemy's ground forces.

After this first phase in Texas, I went to a couple of Air Force bases here in California and learned how to jump out of planes, and then up to Washington state to survival school. This was three weeks and no fun at all. It was cold as hell. I guess so we could learn to survive in the jungle. Never did figure that one out. We did things like getting dropped in the mountains in defense teams and learn E&E — that's the process of escape and evasion. You divide the three-man team up into certain functions — one guy scrounges for food, the other tires to learn the lay of the land, that sort of thing. We were out for two days with half a parachute and a knife between us. Strangely enough, we did manage to build a snare and catch a rabbit. We cooked it over a fire we built with some matches we'd smuggled. it was awful. We'd also smuggled five candy bars, though, and they were pretty good. Then we got captured by some soldiers wearing black pajamas. They put us in cells and tried to break us. It was a game, but they played it serious even though we didn't. it had its ludicrous moments. They played Joan Baez peacenik songs over the loudspeaker.This was supposed to make us think that the people back home didn't support us anymore and we'd better defect. We dug the music,of course. After this, I shipped out.

Q. How long were you in Vietnam?

A. Thirteen months, from 1968 to 1969.

Q. Where were you stationed?

A. In Pleiku most of the time.

Q. Is that where the major intelligence work is done?

A. No, there's a unit in Da Nang that does most of the longer-range work, and the major unit is at Phu Bai. It's the most secure base in Vietnam. An old French base, just below Hue and completely surrounded by a mine field. It's under attack right now. The people based there — a couple of thousand of them — will probably be the last ones out of Vietnam. I don't know if you know of this or not, but the first American killed in Vietnam was at Phu Bai. He was in NSA, working on short-range direction finding out of an armored personnel carrier — you know, one those vans with an antenna on top. It was in 1954. We were told this to build up our esprit de corps.

Q. So what kinds of things did you do there?

A. Like I said, radio direction finding is the big thing, the primary mission. There are several collection techniques used there. Almost all of them are involved with the airborne platforms I mentioned. They are C-47s, "gooney birds," with an E in front of the C-47 because they're involved in electronic warfare. The missions go by different names. Our program was Combat Cougar. We had two or three operators on board and an analyst, which was me. The plane was filled with electronic gear, radios and special DF-ing equipment, about $4 million worth of it, all computerized and very sophisticated. The technology seemed to turn over every five months. As a sideline, I might tell you that an earlier version of this equipment was used in Bolivia, along with infrared detectors, to help track down Che Guevara.

Q. So what would be your specific mission?

A. Combat Cougar planes would take off and fly a particular orbit in a particular part of Indochina. We were primarily tasked for low-level information. that is, we'd be looking for enemy ground units fighting or about to be fighting. This was our A-1 priority. As soon as we locate one of these units through our direction finding, we'd fix it. This fix would be triangulated with fixes made by other airborne platforms, a medium-range direction finding outfit on the ground, or even from ships. Then we'd send the fix to the DSUs on the ground — that's direct support units — at Phu Bai or Pleiku. They'd run it through their computers and call in B-52s or artillery strikes.

Q. How high did you fly?

A. It was supposed to be 8000 feet, but we couldn't get close enough, so we went down to 3000.

Q. You hear a lot about seismic and acoustic sensors and that sort of thing being used. How did this fit into what you were doing?

A. Not at all. They weren't that effective. A lot of them get damaged when they land; some of them start sending signals and get stuck; others are picked up by the Vietnamese and tampered with. Those that come through intact can't tell civilian from military movements. Whatever data is collected from sensors on the trail and at the DMZ is never acted on until correlated with our data.

Q. How did the NVA and NLF troops communicate their battle orders? They seem to take us by surprise, while from what you said earlier the Soviet Union can't.

A. That's because there are no grand battle orders except in a few cases. Almost everything is decided at a low level in the field. That's why most of our intelligence was directed toward those low-level communications I've been talking about. NSA operations in Vietnam are entirely tactical, supporting military operations. Even the long-range stuff, on North Vietnamese air defense and diplomacy, on shipping in and out of Haiphong — the data collected at Da Nang, Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines and somewhat in Thailand — is used in a tactical sense only. It's for our bombers going into North Vietnam. they aren't engaged in probing or testing the defenses of a targeted entity like in Europe. It's all geared around the location of enemy forces.

Q. What would be the effect if the U.S. had to vacate ground installations like the ones you've mentioned?

A. Well, we wouldn't have that good intelligence about the capabilities of the North Vietnamese to shoot our planes down. We wouldn't know what their radar was doing or could do, where their ground-to-air missile sites were, when their MIGs were going to scramble. We'd still be able to DF their troops in the field of course. that won't change until our air forces, including the airborne platforms I flew on, go out too.

Q. NVA and NLF troops must have some sort of counter-measures to use against operations like the ones you were in. Otherwise they wouldn't be as effective as they are.

A. Basically, you're right, although you shouldn't underestimate the kind of damage done by the strikes we called in as a result of our direction finding. To a certain extent, though, the Vietnamese have developed a way to counteract our techniques. Their headquarters in the North is known as MRTTH — Military Region Tri Tin Hue. It is located on the other side of the Valley, somewhere just into Laos. MRTTH has a vast complex of antennas strung all over the jungle. When they're transmitting orders, they play with the switchboard, and the signal goes out over a several-mile area from these different antennas. When you're up in one of these airborne platforms, the effect is like this: you get a signal and fix it. First it will be nine miles in one direction and then, say, twelve miles in another, and fifteen in another. We never found MRTTH. It's one of the high priorities.

Q. But you'd say that the sort of data you collected through DF-ing had some effect?

A. Right, generally. At least in locating field units. It also leads to some large actions. For instance, the first bombing that ever occurred from ARDF data occurred in 1968. There was an area about 19 kilometers southwest of Hue that we'd been flying over. Some of the communications we collected and pattern analysis that was performed on it indicated that there were quite a few NVA or VC units concentrated in a small area, about a mile in diameter. General Abrams personally ordered the largest B-52 raid that had ever taken place in Vietnam at that time. There was one sorties and hour for thirty-six hours, thirty tons dropped by each sortie on the area. Afterwards it was just devastated. I mean it was wasted. It was along time before they could even send helicopters into that area to evaluate the strike because of the stench of burning flesh. On the perimeter of the area there were Vietnamese that had died just from the concussion. The thing of it was, though, there wasn't any way to tell which of the dead were military and which were civilian. It was pretty notorious. Afterwards it was called Abrams Acres. It was one of the things that began to turn me off to the war.

Q. You said that your A-1 priority was locating enemy units on the ground. What were the other targets?

A. Mainly supplies. We tried, not too successfully, to pinpoint their supply capabilities. All along the Trail the Vietnamese have these gigantic underground warehouses known as "bantrams," where either men or supplies are housed. The idea is that in case of an offensive like the one that's going on now, they don't have to go north for supplies. They've got them right there in these bantrams, enough to last for a long time at a fairly high level of military activity. They had about 11 bantrams when I was there. We knew where they were within twenty-five or thirty miles, but no closer. I remember the first Dewey Canyon invasion of Laos. I flew support for it. It happened because the 9th Marines went in there to locate a couple of bantrams. Their general was convinced he was going to end the war. It was a real macho trip. He got called back by the White House pretty quick, though, when his command got slaughtered.

Q. What about the idea of an invasion from the north. How does this equate with what you collected?

A. It doesn't. There's no invasion. The entire Vietnamese operation against Saigon and the U.S. is one unified military command throughout Indochina. Really, it's almost one country. They, don't recognize borders: that's seen in their whole way of looking at things, their whole way of fighting.

Q. But you made a distinction between VC and NVA forces didn't you?

A. There are forces we'd classify as VC and others as NVA, yes. But it was for identification, like the call signs on Soviet planes. The VC forces tended to merge, break apart, then regroup, often composed differently from what they were before. As far as the NVA is concerned, we'd use the same names they were called back home, like the 20th regiment. Hanoi controls infiltration, some troops and supplies coming down the Trail. But once they get to a certain area, MRTTH takes over. And practically speaking. MRTTH is controlled by the NLF-PRG.

Q. How did you know that?

A. We broke their messages all the time. We knew the political infrastructure.

Q. You mean that your intelligence would have in its official report that this MRTTH base which was on the other side of the Ashau Valley, was controlled by the NLF?

A. Of course. Hanoi didn't control that area operationally. MRTTH controls the whole DMZ area. Everything above Da Nang to Vinh. The people in control are in the NLF. MRTTH makes the decisions for its area. Put it this way: it is an autonomous political and military entity.

Q. What you're saying is that in order to gather intelligence and operate militarily, you go on the assumption that there is one enemy? That the NLF is not subordinate to the North Vietnamese Command?

A. Right. That's the way it is. This is one thing I wish we could bring out. Intelligence operates in a totally different way, from politics. The intelligence community generally states things like they are. The political community interprets this information. changes it, deletes some facts and adds others. Take the CIA report that bombing in Vietnam never really worked, That was common knowledge over there. Our reports indicated it. Infiltration always continued at a steady rate. But of course nobody back at the military command or in Washington ever paid any attention.

Q. What were some of the other high intelligence priorities besides locating ground units, MRTTH and the bantrams?

A. One of the strange ones came from intelligence reports we got from the field and copies from North Vietnam. These reports indicated that the NLF had two Americans fighting for them in the South. We did special tasking on that. We were on the lookout for ground messages containing any reference to these Americans. Never found them, though.

Q. When you were there in Vietnam did you get an idea of the scope of U.S. operations in Southeast Asia or were you just involved with these airborne platforms exclusively?

A. I was pretty busy. But I took leaves, of course, and I saw a lot of things. One thing that never came out, for example, was that there was a small war in Thailand in 1969. Some of the Meo tribesmen were organized and attacked the Royal Thai troops for control of their own area.

Q. What happened to them?

A. Well, as you know, Thailand is pretty important to us. A stable Thailand, I mean. CAS-Vientiane and CAS-Bangkok were assigned to put down the uprisings.

Q. What does CAS mean?

A. That's the CIA's designation. Three of our NSA planes were taken to Udorn, where the CIA is based in Thailand, and flew direct support for CIA operations against the Meos. We located where they were through direction finding so the CIA planes could go in and bomb them.

Q. You mean CIA advisors in Thai Air Force planes?

A. No. The CIA's own planes. Not Air America — those are the commercial-type planes used just for logistics support. I'm talking about CIA military planes. They were unmarked attack bombers.

Q. What other covert CIA operations in the area did you run into?

A. From the reports I saw, I knew there were CIA people in southern China, for instance, operating as advisors and commanders of Nationalist Chinese commando forces. It wasn't anything real big. They'd go in and burn some villages, and generally raise hell. The Chinese always called these "bandit raids."

Q. What would be the objectives of these raids besides harassment?

A. There's some intelligence probing. And quite a bit of it is for control of opium trade over there. Nationalist Chinese regular officers are occasionally called in to lead these maneuvers. For that matter, there are also CIA-run Nationalist Chinese forces that operate in Laos and even in North Vietnam.

Q. Did you ever meet any of these CIA people?

A. Sure. Like I said, I flew support for their little war in Thailand. I remember on the guys there in Vientiane that we were doing communications for, said he'd been into Southern China a couple of times.

Q. You got disillusioned with the whole Vietnam business?

A. Yes.

Q. Why?

A. Well, practically everybody hated it. Everybody except the lifers who were in the military before Vietnam. Even after that wasting of the area called Abram's Acres that I told you about before, everybody else was really sick about it, but these lifers kept talking about all the commies we had killed.

For me, part of it was when we crashed our EC-47. We'd just taken off and were at about 300 feet and it just came down. We crash-landed in a river. We walked out of it, but I decided that there was no easy way to get me into an airplane after that. We got drunk that night, and afterwards I spent two weeks on leave in Bangkok. When I got back to Saigon i got another three days vacation in Na Trang. The whole thing was getting under my skin. I told them that I wasn't going to fly any more. And mainly they left me alone. They figured I'd snap out of it. But finally they asked me what my reasons for refusing to fly were. I told them that it was crazy. I wasn't going to crash anymore, I wasn't going to get shot at anymore, I was afraid. I told the flight operations director that I wasn't going to do it anymore, I didn't care what was done to me. Strangely enough, they let me alone. They decided after a few days to me Air Force liaison man up at Phu Bai. So I spent the last three months up there correlating data coming in from airborne platforms. Like the one I'd flown in and sending DSU reports to the B-52s. It happened all of a sudden, my feeling that the whole war was rotten. I remember that up at Phu Bai there were a couple of other analysts working with me. We never talked about it, but we all wound up sending the bombers to strange places — mountain tops, you know, where there weren't any people. We were just biding our time till we got out. We were ignoring priorities on our reports, that sort of thing.

It's strange. When I first got to Nam, everybody was still high about the war. But by the time I left at the end of 1969, morale had broken down all over the place. Pot had become a very big thing. We were even smoking it on board the EC-47s when we were supposed to be doing direction finding. And we were the cream of the military, remember.

I loved my work at first. It was very exciting — traveling in Europe, the Middle East, Africa; knowing all the secrets. It was my whole life, which probably explains why I was better than others at my job. But then I went to Nam, and it wasn't a big game we were playing with the Soviets anymore. It was killing people. My last three months in Nam were very traumatic. I couldn't go on, but I wasn't able to quit. Not then. So faked it. It was all I could do. Now I wish I had quit. If I had stayed in Europe, I might still be in NSA. I might have re-enlisted. In a way, the war destroyed me.