Robin Cook

(politician) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Robert Finlayson Cook 1946-02-28 Bellshill, Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2005-08-06 (Age 59) Inverness, Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of | The Other Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Labour, Party of European Socialists | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Finlayson "Robin" Cook (28 February 1946 – 6 August 2005) was a British Labour Party politician, who was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Livingston from 1983 until his death, and notably served in Tony Blair's Cabinet as Foreign Secretary from 1997 to 2001.

Robin Cook studied at the University of Edinburgh before becoming an MP for Edinburgh Central in 1974. In parliament he was noted for his debating ability which saw his rise through the political ranks and ultimately to the Cabinet.

He resigned from his positions as Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons on 17 March 2003 in protest against the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[1] At the time of his death, he was President of the Foreign Policy Centre and a vice-president of the America All Party Parliamentary Group and the Global Security and Non-Proliferation All Party Parliamentary Group.

Contents

Early life

Robin Cook was born in the County Hospital, Bellshill, Scotland, the only son of Peter and Christina Cook (née Lynch). His father was a chemistry teacher who grew up in Fraserburgh, and his grandfather was a miner before being blacklisted for being involved in a strike.

Cook was educated at Aberdeen Grammar School and, from 1960, the Royal High School in Edinburgh. At first, Cook intended to become a Church of Scotland minister, but lost his faith as he discovered politics. He joined the Labour Party in 1965 and became an atheist. He remained so for the rest of his life. He then studied English Literature at the University of Edinburgh, where he obtained a Master of Arts degree with Honours in English Literature. He began studying for a PhD on Charles Dickens and Victorian serial novels, supervised by the author John Sutherland, but gave it up in 1970.

In 1971, after a period working as a secondary school teacher, Cook became a tutor-organiser of the Workers' Educational Association for Lothian, and a local councillor in Edinburgh. He gave both up when elected an MP on his 28th birthday, in February 1974.

Personal life

Robin Cook also worked as a racing tipster in his spare time. He was introduced to horse racing by his wife, Margaret Katherine Whitmore, from Somerset, whom he met whilst at Edinburgh University. They married on 15 September 1969 at St Alban's Church, Westbury Park, Bristol and had two sons, Peter and Christopher, born in February 1973 and May 1974. Between 1991 and 1998 Cook wrote a weekly tipster's column for the Glasgow Herald newspaper.

Shortly after he became Foreign Secretary, Cook ended his marriage with Margaret, revealing that he had an extra-marital affair with one of his staff, Gaynor Regan.[2] He announced his intentions to leave his wife and marry another woman via a press statement made at Heathrow on 2 August 1997. Cook was forced into a decision over his private life after a telephone conversation with Alastair Campbell as he was about to go on holiday with his first wife. Campbell explained that the press was about to break the story of his affair with Regan. His estranged wife subsequently accused him of being insensitive during their marriage, of having had several extramarital affairs and alleged he was an alcoholic.

Robin Cook married Gaynor Regan in Tunbridge Wells, Kent[3] on 9 April 1998, four weeks after his divorce was finalised.

Early years in Parliament

Cook unsuccessfully contested the Edinburgh North constituency in the 1970 general election, but was elected to the House of Commons at the February 1974 general election as MP for Edinburgh Central, defeating George Foulkes for the nomination. When the constituency boundaries were revised for the 1983 general election, he transferred to the new Livingston constituency, beating Tony Benn to the selection, which he represented until his death.

In parliament, he joined the left-wing Tribune Group of the Parliamentary Labour Party and frequently opposed the policies of the Wilson and Callaghan governments. He was an early supporter of constitutional and electoral reform (although he opposed devolution in the 1979 referendum, eventually coming out in favour on election night in 1983), and of efforts to gain more women MPs. He also supported unilateral nuclear disarmament and the abandoning of the Labour Party's euroscepticism of the 1970s and 1980s. During his early years in parliament Cook championed several liberalising social measures, to mixed effect. He repeatedly (and unsuccessfully) introduced a private member's bill on divorce reform in Scotland, but succeeded in July 1980 — and after three years' trying — with an amendment to bring the Scottish law on homosexuality into line with that in England.

After Labour lost power in May 1979, Robin Cook encouraged Michael Foot's bid to become party leader and joined his campaign committee. When Tony Benn challenged Denis Healey for the party's deputy leadership in September 1981, Cook supported Healey.

In opposition

Robin Cook was known as a brilliant parliamentary debater, and rose through the party ranks, becoming a frontbench spokesman in 1980, and reaching the Shadow Cabinet in 1987, as Shadow Social Services Secretary. He was campaign manager for Neil Kinnock's successful 1983 bid to become leader of the Labour Party, and was one of the key figures in the modernisation of the Labour Party under Kinnock. He was Shadow Health Secretary (1987–92) and Shadow Trade Secretary (1992–94), before taking on foreign affairs in 1994, the post he would become most identified with (Shadow Foreign Secretary 1994-97, Foreign Secretary 1997-2001).

Arms to Iraq

In November 1992, Cook led the parliamentary attack on the Tory government's role in the Arms-to-Iraq affair:

The 1985 guidelines did not merely ban lethal equipment but also any defence equipment which would significantly enhance military capability. Between 1988 and 1990, we did just that, and Ministers knew it, because in 1989 they received a report from the Ministry of Defence entitled: British assistance to the emerging Iraqi arms industry, which listed in its appendix five pages of companies providing defence equipment to Iraq, and which came to the conclusion that assistance from British companies had helped to build "a very significant enhancement to the ability of Iraq to manufacture its own arms, thus to resume the war with Iran." The Ministry of Defence concluded that Ministers had broken the guideline not to enhance military capability.

I notice that, in the amendment, the Government accuse us of "sensationalised" disclosures. If we have been sensational, it is only because we have published documents that show what Ministers did in meetings. I would not disagree with their choice of words. The picture that emerges from those documents is of Ministers arming one of the world's most brutal regimes and breaking their guidelines to do it. I agree with those on the Government Front Bench that that is sensational, and the Government knew it. We know that because, when the document was first produced in 1989, it was unclassified. In December 1990, it was marked "Restricted" in handwriting. Why? Would someone on the Government Front Bench like to tell us? It was not as if the document would have been of any value to our enemy in the Gulf war. Saddam knew what we had provided--he knew rather more than the British Parliament. The document was reclassified because the Government became embarrassed at the major role which Britain had played in rebuilding a war machine that British troops had to fight.

There is another reason why Ministers might well be embarrassed. They not only helped to arm Saddam, but it looks as if Britain will have to pick up most of the bill. The Government agreed a new credit facility to Iraq in 1987, and the then Chief Secretary to the Treasury approved it--he is now the Prime Minister.[4]

Scott Report

On 26 February 1996, following the publication of the Scott Report into the 'Arms-to-Iraq' affair, he made a famous speech in response to the then President of the Board of Trade Ian Lang in which he said "this is not just a Government which does not know how to accept blame; it is a Government which knows no shame". His parliamentary performance on the occasion of the publication of the five-volume, 2,000-page Scott Report – which he claimed he was given just two hours to read before the relevant debate, thus giving him three seconds to read every page – was widely praised on both sides of the House as one of the best performances the Commons had seen in years, and one of Cook's finest hours. The government won the vote by a majority of one.

Constitutional Reform

As Joint Chairman (alongside Liberal Democrat MP Robert Maclennan) of the Labour-Liberal Democrat Joint Consultative Committee on Constitutional Reform, Cook brokered the 'Cook-Maclennan Agreement' that laid the basis for the fundamental reshaping of the British constitution outlined in Labour's 1997 General Election manifesto. This led to legislation for major reforms including Scottish and Welsh devolution, the Human Rights Act and removing the majority of hereditary peers from the House of Lords. Others have remained elusive so far, such as a referendum on the electoral system and further House of Lords reform. However, in 2011 voters in the United Kingdom were finally given the chance to have their say on replacing the first-past-the-post voting system with the Alternative Vote method in a referendum held on 5 May. On 6 May 2011, it was announced that any proposed move to the AV voting system had been rejected (by the minority of the electorate who voted) by a margin of 67.9% to 32.1%.

Foreign Secretary

With the election of a Labour government at the 1997 general election, Robin Cook became Foreign Secretary. He was believed to have coveted the job of Chancellor of the Exchequer, but that job was reportedly promised by Tony Blair to Gordon Brown.

Foreign Secretary Robin Cook announced, to much scepticism, his intention to add "an ethical dimension" to foreign policy.[citation needed] Cook is credited with having helped resolve the eight-year impasse over the Lockerbie bombing trial by getting Libya to agree to hand over the two accused (Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah) in 1999, for trial - conducted according to Scots law - in the former US Air Force base Camp Zeist in the Netherlands.

Cook once observed that he never knew Downing Street make any decision that displeased BAE Systems. [5]

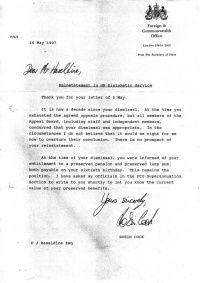

No reinstatement of Patrick Haseldine

On 5 May 1997 former British diplomat Patrick Haseldine, who had been sacked in 1989 for criticising Margaret Thatcher and for accusing apartheid South Africa of targeting Bernt Carlsson on Pan Am Flight 103, wrote congratulating Robin Cook on his appointment – after the landslide election victory of the New Labour government – and asked for reinstatement in HM Diplomatic Service. The Foreign Secretary replied in a letter dated 16 May 1997:

- "It is now a decade since your dismissal. At the time you exhausted the agreed appeal procedures, but all members of the Appeal Board, including staff and independent members, concurred that your dismissal was appropriate. In the circumstances I do not believe it would be right for me now to overturn their conclusion. There is no prospect of your reinstatement."

Undaunted, Haseldine then asked his MP (Eric Pickles) and MEP (Hugh Kerr) to intercede with Robin Cook on his behalf.

Lockerbie bombing and South Africa

On 8 December 1997, Patrick Haseldine sent a letter headed "Lockerbie bombing and South Africa" to Robin Cook:

- Thank you for your letter of 16th May 1997 in which you declined to reinstate me in HM Diplomatic Service. In taking that decision, I believe that you were wrongly advised: this is why.

- I was dismissed for writing a letter to The Guardian on 7th December 1988 which inter alia repeated the accusation first made by Governor Michael Dukakis during the US Presidential election campaign in 1988 that South Africa was a "terrorist state". Flight Pan Am 103 was then sabotaged over Lockerbie on 21st December 1988.

- Once it was known that a South African delegation were booked on that flight but had cancelled and that the UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, had been killed in the crash, I was convinced that the apartheid régime was responsible.

- Paragraph 67 of the record of the Appeals Board Hearing, to which your letter referred, confirms that this was my view.

- I presented a dossier of evidence in support of this view to the Lord Advocate for Scotland early in 1996 and copied the document to you as Shadow Foreign Secretary. On 3rd February 1997, Lord Steel of Aikwood replied (Attachment A) to my letter seeking his support for reinstating me and for an investigation into the South Africa/Lockerbie connection. Lord Steel took up the matter of Pik Botha's cancellation on Pan Am 103 with Lord Mackay of Drumadoon who replied to him on 4th March (B).

- The Lord Advocate referred to a Reuters report of 12th November 1994.

- Thanks to the editor-in-chief of Reuters (C), I recently managed to obtain a copy of that report which I am now forwarding to you (D).

- The Reuters report raises many questions, eg:

- a. why did the inward flight from Johannesburg by-pass the scheduled stopover in Frankfurt (South African Airways European HQ)?

- b. as well as being booked on Pan Am 103 from Heathrow, were Pik Botha and the "22 South African negotiators" also booked on the feeder flight Pan Am 103A from Frankfurt?

- c. the arrival at Heathrow of the South African party "an hour early" does not explain how Pik Botha caught flight Pan Am 101, the ETD of which was seven hours earlier than Pan Am 103.

- In the BBC Frontline Scotland programme "Silence over Lockerbie" on 14th October 1997, Michael Mansfield QC comprehensively demolished the case against the Libyans. I am prepared to assist in any way I can to bring the Lockerbie terrorists to justice. Please let me know how I can help.

- Yours ever,

- Patrick Haseldine

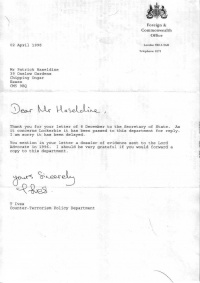

FCO response

- Dear Mr Haseldine,

- Thank you for your letter of 8 December 1997 to the Secretary of State.

- As it concerns Lockerbie it has been passed to this department for reply. I am sorry it has been delayed.

- You mention in your letter a dossier of evidence sent to the Lord Advocate in 1996. I should be very grateful if you would forward a copy to this department.

- Yours sincerely,

- T Ives

- Counter-Terrorism Policy Department

- Foreign & Commonwealth Office

South Africa and the Lockerbie bombing

Haseldine replied to the FCO on 26 April 1998:

- Trudie Ives

- Counter-Terrorism Policy Department

- Foreign & Commonwealth Office

- King Charles Street

- LONDON SW1A 2AH

- Thank you for your acknowledgment dated 2nd April 1998 of my letter sent to the Foreign Secretary on 8th December last year.

- You have asked me to forward a copy of the dossier of evidence submitted two years ago to the Lord Advocate. I do not have a copy of the dossier readily available and would therefore suggest you contact the Lord Advocate's Private Secretary or Mr J A Dunn, Senior Legal Assistant at the Crown Office in Edinburgh, and get them to provide you with a copy. I enclose file-referenced letters dated 23rd January and 13th February 1996 from Edinburgh to facilitate locating this dossier.

- When you are in touch with the Lord Advocate's Office, you could usefully ask what action they have taken/are taking to inculpate the apartheid régime with the Lockerbie bombing. My letter of 6th January 1997 to the former Foreign Secretary (copy enclosed) - which referred to the dossier sent to the Lord Advocate - also detailed further evidence indicating South African involvement.

- Please let me know if I can be of assistance with any aspect of the Lockerbie investigation.

- Yours ever,

Lockerbie breakthrough

On 5 April 1999, Robin Cook announced that there had been a breakthrough in bringing to trial those accused of the Lockerbie bombing:

- Two years ago when I first entered this building I asked for a review on the Lockerbie file. The conclusion I came to was that we were getting nowhere; and I found it hard to meet the relatives of the victims, and to hear from them how they could see no prospect of obtaining justice or of seeing a legal process. I came to the conclusion that we could not secure progress on Lockerbie without a fresh initiative, and at the end of 1997 when Madeleine Albright stayed with me at Christmas, we agreed that we would try to put together an initiative for a trial in a third country as an offer to the Libyan government.

- I will be frank, I am not entirely sure, when we started out on that process, that we understood quite what a long slog we were letting ourselves in for. It took 9 months of tough legal negotiation in order to secure the arrangements for that trial in a third country. I would want to express my thanks to the government of the Netherlands who willingly agreed to be the host for the trial and have reinforced the Netherlands' reputation as a seat of international justice. I have visited Camp Zeist, which they have made available to us and which is now under Scottish jurisdiction. Camp Zeist will provide excellent facilities for a modern courtroom, a strong prison and also a very large gymnasium for the ladies and gentlemen of the press who will be in attendance at the court.

- I would also want to record my appreciation of the close cooperation that we have had throughout this entire project from the Lord Advocate and his staff, without whose whole-hearted commitment to this project we would not have succeeded in making those legal arrangements.

- We launched the initiative in August in this room, and since then we have put in long, hard, patient, diplomatic effort. I do not think there has been a week since August in which at some time I have not asked what effort more we can put in to convincing Libya that this was an offer made in good faith and without a hidden agenda. By the end of last year we had met all the concerns of the Libyan government, bar one - which was the place of imprisonment - and for a while it looked as if negotiations would break down over the demand by Libya that if convicted the two suspects should not serve their sentence in Scotland. That was a point of principle on which we could not compromise, and on which we have not compromised.

- But at the end of the year I did offer that we would accept UN observers to monitor the conditions and the health of the two suspects if they were convicted. We have nothing to be ashamed of in Scottish prisons, we have nothing to hide, we are very happy to welcome that international observation provided our requirement that if sentences are passed are served in Scottish jurisdiction, in Scottish prisons. That offer appears to have cleared the last obstacle and all that effort and those patient negotiations have today brought the handover of the two suspects who are about to land in the Netherlands where they will quickly be handed over to Scottish jurisdiction. When that happens I will instruct our representatives at the United Nations to confer with the Secretary-General about starting the process to suspend sanctions on Libya.

- I would want to state that it is not for me or for the government to judge whether these two men are innocent or guilty, that is a matter for the court, and they will have a fair trial in that court. I have always stressed that if the two men are innocent they have nothing to fear from Scottish justice. The obligation for the Foreign Office and for government was to secure the presence of the two accused before a court, and that we have now done.

- Today's development is important as a breakthrough for three reasons: first, this breakthrough ends a stalemate of 10 years in diplomatic relations and negotiations; secondly, it creates legal history, this is the first time that any country has attempted to carry out a trial under its laws and procedures in a third country; and thirdly it is important because of the relief that it can bring to the relatives of those who died that night over and in Lockerbie. I have met them a number of times over the past 18 months. The most difficult thing for me is that I have not been able to tell them what we know and what we suspect about what happened to their loved ones. Now those relatives will have the opportunity of hearing in open court all the evidence we have which is the result of the longest and largest police investigation in British history. Just before coming here I met with Pam Dix, the Secretary of the UK Families Group. She expressed her huge relief at this development today.

- Often what we do in this building as diplomats must appear remote to the people we serve. In this case diplomacy is having a direct impact on the lives and the emotions of our people. Some people have said in the past that there never would be a trial into the Lockerbie bombing. I must confess there have been moments in the past year when I wondered if they might be right - but we have now proved them wrong, we have secured the surrender of the two suspects and there is going to be a criminal trial into this act of mass murder.

QUESTION: How crucial was Nelson Mandela's role in this whole business? How significant was his statement at the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Edinburgh in 1997 about the inappropriateness of having a trial in Scotland?

FOREIGN SECRETARY: Nelson Mandela and a number of other international leaders, particularly from Saudi Arabia, have been very helpful to us in securing this outcome. You are absolutely right to pick up that Nelson Mandela proposed a trial in a third country at the CHOGM in Edinburgh in October 1997, and one of the great strengths of our initiative was that these people such as Nelson Mandela had made that suggestion after consulting with the government of Libya. And when we accepted that proposal and made it as an offer to Libya, they were then able to go back to Tripoli and say, 'look, you asked us to invite Britain to make that offer, they have now made that offer, having put our own reputation behind the offer we want you to accept it.' That pressure, I think, was very helpful in getting the result. I would also wish to particularly mention the work of Kofi Annan and his legal team. We tasked them in August with making the arrangements for the handover and negotiating the detailed agreement with the government of Libya, I know that they have put in many, many hours of negotiation to make this possible and we are grateful for their patient diplomacy.

QUESTION: How quickly do you anticipate relations between the UK and Libya to get back to normal?

FOREIGN SECRETARY: The United Nations sanctions will now be suspended, and after 90 days will be lifted depending on Kofi Annan's support; that will resolve the international sanctions on Libya.

The United Kingdom does of course also have issues of its own bilateral concerns with Libya, notably the case of the murder of WPC Fletcher. We have said that we would wish to address those issues, and we hope to achieve cooperation with Libya in resolving those issues - hopefully with some good reasonable speed now that we have resolved the Lockerbie case.

QUESTION: If the two men are found guilty, are you expecting the Libyan government to pay compensation?

FOREIGN SECRETARY: Yes, if the two are found guilty and if they acted on behalf of the Libyan state, we would expect the Libyan state to pay compensation. Currently that is what is underway in relation to the UTA bombing where France has produced a guilty verdict against six Libyans, and where it appears that compensation will be paid. So there is that precedent, and we would expect Libya to meet compensation in those circumstances, but that of course can only happen once we have a verdict from the court.[6]

Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Kashmir and Israel

Robin Cook's term as Foreign Secretary was marked by British interventions in Kosovo and Sierra Leone. Both of these were controversial, the former because it was not sanctioned by the UN Security Council, and the latter because of allegations that the British company Sandline International had supplied arms to supporters of the deposed president in contravention of a United Nations embargo. Cook was also embarrassed when his apparent offer to mediate in the dispute between India and Pakistan over Kashmir was rebuffed. The ethical dimension of his policies was subject to inevitable scrutiny, leading to criticism at times.

In March 1998, a diplomatic rift ensued with Israel when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu angrily cancelled a dinner with Cook, while Cook was visiting Israel and had demonstrated opposition to the expansion of Israeli settlements.[7]

Leader of the House of Commons

After the 2001 general election Robin Cook was moved, against his wishes, from the Foreign Office to be Leader of the House of Commons. This was widely seen as a demotion - although it is a Cabinet post, it is substantially less prestigious than the Foreign Office - and Cook nearly turned it down. In the event he accepted, and looking on the bright side welcomed the chance to spend more time on his favourite stage. According to The Observer,[8] it was Blair's fears over political battles within the Cabinet over Europe, and especially the euro, which saw him unexpectedly demote the pro-European Cook.

As Leader of the House he was responsible for reforming the hours and practices of the Commons and for leading the debate on reform of the House of Lords. He also spoke for the Government during the controversy surrounding the membership of Commons Select Committees which arose in 2001, where Government whips were accused of pushing aside the outspoken committee chairs Gwyneth Dunwoody and Donald Anderson. He was President of the Party of European Socialists from May 2001 to April 2004.

In early 2003, during a live television appearance on BBC current affairs show "Question Time", he was inadvertently referred to as "Robin Cock" by David Dimbleby. Cook responded with attempted good humour with "Yes, David Bumblebee", and Dimbleby apologised twice on air for his slip. The episode also saw Cook in the uncomfortable position of defending the Government's stance over the impending invasion of Iraq, weeks before his resignation over the issue.

Robin Cook documented his time as Leader of the House of Commons in a widely acclaimed book "The Point of Departure", which discussed in diary form his efforts to reform the House of Lords and to persuade his ministerial colleagues, including Tony Blair, to distance the Labour Government from the foreign policy of the Bush administration. The former Political Editor of Channel 4 News, Elinor Goodman called the book 'the best insight yet into the workings of the Blair cabinet', whilst the former Editor of The Observer, Will Hutton, called it "the political book of the year - a lucid and compelling insider's account of the two years that define the Blair Prime Ministership."

Resignation over Iraq war

In early 2003 Robin Cook was reported to be one of the Cabinet's chief opponents of military action against Iraq, and on 17 March 2003 he resigned from the Cabinet.[9] In a statement giving his reasons for resigning he said:

- "I can't accept collective responsibility for the decision to commit Britain now to military action in Iraq without international agreement or domestic support." He also praised Blair's "heroic efforts" in pushing for the so-called second resolution regarding the Iraq disarmament crisis, but lamented "The reality is that Britain is being asked to embark on a war without agreement in any of the international bodies of which we are a leading partner—not NATO, not the European Union and, now, not the Security Council". Cook's resignation speech in the House of Commons, received with an unprecedented standing ovation by fellow MPs, was described by the BBC's Andrew Marr as "without doubt one of the most effective, brilliant, resignation speeches in modern British politics."[10] Most unusually for the British parliament, Cook's speech was met with growing applause from all sides of the House (beginning with Labour and Liberal Democrat critics of the war), and from the public gallery. According to The Economist's obituary, that was the first speech ever to receive a standing ovation in the history of the House.[11]

Iraq Inquiry

In The Guardian of 3 February 2010 David Clark, who joined Robin Cook's staff in 1994 and served as his special adviser at the Foreign Office from 1997 to 2001, wrote "The witness the Iraq Inquiry really misses is Robin Cook. But even from the grave my old boss's testimony is damning". He continued:

In one of the more unusual asides of the Iraq inquiry, Jack Straw suggested that Chilcot should "talk to Robin Cook about this". Sadly, that won't be possible. As Lord Turnbull, the former cabinet secretary, pointed out, Cook is not here to take the credit he deserves for having been "spot on" about Iraq. More importantly, he isn't available to tell the inquiry why he differed from colleagues who insisted that war was essential, by following the same intelligence to a different conclusion and why, unlike Clare Short, he refused to be "conned". Even so, Straw's slip was understandable. So close was Cook's association with the great issue of Iraq that he has often seemed to be present in spirit, if not in person, as the decisions that led Britain to war have been laid bare.

This is about more than nostalgia. Cook's relevance to Chilcot is not primarily as the conscience of a government that erred. He is important because he represents the road not taken, the historical counterfactual, proof negative against Alastair Campbell's claim that everyone who saw the evidence accepted that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. By resigning from the cabinet he showed that it could have been different.

Although Cook cannot follow Short on to the witness stand, he wrote and said enough about the build-up to war to corroborate and expand on much of what she told the inquiry about how the government's Iraq policy was formed. Cook's diaries contain insights about the mindset of colleagues and the way they responded to events. They show a government for whom the real nature of the threat posed by Iraq was subsidiary to other considerations: for Blair the imperative was sticking close to Washington; for most of his colleagues it was about loyalty to him. This was confirmed in Straw's testimony when he admitted to swallowing private reservations in order to stand by his prime minister. In this atmosphere, the intelligence picture and legal arguments that have occupied so much of the inquiry's time were treated not as policy guides, but political obstacles to be overcome.

Cook was almost alone in exploring the case for war on its merits, and his willingness to resign because of it is the best argument against those who insist they were misled by faulty intelligence. On 20 February 2003, Cook received an hour-long private briefing from John Scarlett, in which he quizzed Britain's senior intelligence official on what was really known about WMD. This meeting confirmed his strong belief, expressed in his resignation speech to parliament a month later, that "Iraq probably has no weapons of mass destruction in the commonly understood sense of the term – namely a credible device capable of being delivered against a strategic city target". This ran counter to the impression cultivated by the government. Remember that the Commons motion authorising war claimed that "Iraq's weapons of mass destruction and long-range missiles … pose a threat to international peace and security".

Cook understood that there was no sound basis for this claim. On the contrary, it was increasingly clear to him that new intelligence was, if anything, weakening the case for war. This is revealed most significantly in Cook's diary entry for 5 March 2003 covering a private meeting with Tony Blair. He suggested that Iraq's capabilities were limited to battlefield chemical munitions, at worst, to which Blair apparently assented. He then asked if Blair was concerned that these might be used against British troops in an invasion. Blair responded: "Yes, but all the effort he has had to put into concealment makes it difficult for him to assemble them quickly for use."

This exchange shows, first, that Blair knew Iraq did not possess the long-range WMD suggested in the motion tabled before parliament two weeks later. Second, it proves that whatever he believed about the notorious 45-minute claim at the time of the September dossier, he knew it to be false on the eve of war. As we have since discovered, fresh intelligence from late 2002 onwards concluded that the presence of UN inspectors would prevent the assembly and deployment of Saddam's short-range chemical weapons. This was the reason, Cook believed, why the 45-minute claim and other parts of the September dossier were subsequently dropped from government pronouncements. Why then was no effort made to correct the parliamentary record? Blair's failure to reflect the changing intelligence picture in what he claimed about Iraq is something that Chilcot ought to look into.

The official assessment in early 2003, as understood by both Cook and Blair, was that Iraq probably possessed a short-range capability that was disassembled and locked away because of the presence of UN weapons inspectors. In other words, it showed that containment was working. The correct policy, as Cook put it to Blair, was to give Hans Blix the time needed to complete Iraq's verified disarmament. Blair's response was not to dispute the logic of that approach, as he did before Chilcot last week, but to state that President Bush would wait no longer. As Cook himself pointed out, the disarmament of Iraq was the last thing his administration wanted because it would have removed the pretext for a war being pursued with very different objectives in mind.[12].

Outside government

Following his 2003 resignation from the Cabinet, Robin Cook remained an active backbench Member of Parliament until his death. After leaving the Government, Cook was a leading analyst of the decision to go to war in Iraq, giving evidence to the Foreign Affairs Select Committee which was later relevant during the Hutton Inquiry and Butler Review inquiries. He was sceptical of the proposals contained in the Government's Higher Education Bill, and abstained on its Second reading.[13] He also took strong positions in favour of both the proposed European Constitution,[14] and a majority-elected House of Lords,[15][16] about which he said (whilst Leader of the Commons):

- "I do not see how the House of Lords can be a democratic second Chamber if it is also an election-free zone".

Relations with Gordon Brown

In the years after his exit from the Foreign Office, and particularly since his resignation from the Cabinet, Cook made up with Gordon Brown after decades of personal animosity[17] – an unlikely reconciliation after a mediation attempt by Frank Dobson in the early 1990s had seen Dobson conclude (to John Smith):

- "You're right. They hate each other."

Robin Cook and Gordon Brown focused on their common political ground, discussing how to firmly entrench progressive politics after the exit of Tony Blair.[18] Chris Smith said in 2005 that in recent years Cook had been setting out a vision of "libertarian, democratic socialism that was beginning to break the sometimes sterile boundaries of 'old' and 'New' Labour labels."[19] With Blair's popularity waning, Cook campaigned vigorously in the run-up to the 2005 general election to persuade Labour doubters to remain within the party.

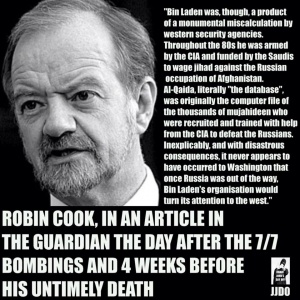

Al-Qaida and the CIA

In a column for the Guardian four weeks before his death, Cook caused a stir when he described Al-Qaida as a product of a Western intelligence:

- "Bin Laden was, though, a product of a monumental miscalculation by Western security agencies. Throughout the 80s he was armed by the CIA and funded by the Saudis to wage jihad against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Al-Qaida, literally "the database", was originally the computer file of the thousands of mujahideen who were recruited and trained with help from the CIA to defeat the Russians.[20]

Mountaineering with Gaynor

Some commentators and senior politicians said that Robin Cook seemed destined for a senior Cabinet post under a Brown premiership.[21]

In early August 2005, Cook and his second wife, Gaynor, took a two-week holiday in the Scottish Highlands. At around 2:20pm, on 6 August 2005, whilst walking down Ben Stack in Sutherland, Scotland, Cook suddenly suffered a severe heart attack, collapsed, lost consciousness and fell about 8ft down a ridge.[22] A helicopter containing paramedics arrived 30 minutes after a 999 emergency call was made. Cook then was flown to Raigmore Hospital, Inverness. Gaynor did not get in the helicopter, and was left to walk down the mountain. Despite efforts made by the medical team to revive Cook in the helicopter, he was already beyond recovery, and at 4:05pm, minutes after arrival at the hospital, was pronounced dead. Two days later, a post-mortem revealed that Cook died of hypertensive heart disease.

A funeral service was held on 12 August 2005, at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, even though Cook had been an atheist.[23] Gordon Brown gave the eulogy, and German foreign minister Joschka Fischer was one of the guests. British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who was on holiday at the time, did not attend. In his speech at the funeral, Cook's friend, the racing pundit John McCririck, criticised Blair for not attending.

A later memorial service at St Margaret's Church, Westminster, on 5 December 2005, included a reading by Tony Blair and warm tributes by Gordon Brown and Madeleine Albright. On 29 September 2005, Cook's friend and election agent since 1983, Jim Devine, won the resulting by-election with a reduced majority.

In January 2007, a headstone was erected in The Grange, Edinburgh Cemetery, where Cook is buried, bearing the epitaph:

- "I may not have succeeded in halting the war, but I did secure the right of parliament to decide on war."

It is a reference to Robin Cook's strong opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the words were reportedly chosen by his widow and two sons from his previous marriage, Chris and Peter.[24]

Wife and mistress

Robin Cook's first wife Margaret said:

- I lived at the other end of the country from the Westminster village and, no doubt to my then husband’s considerable relief, it was unlikely that Gaynor (the then mistress) and I should ever meet for a no-holds-barred showdown. We did have the odd frosty telephone conversation when I had reason to suspect, but was not sure of, her status.

- After Robin had stood before the cameras on the steps of his grand London residence and announced without emotion that he was leaving me, asking for privacy and media restraint (as if!), I actually received enormous support from an unexpected source. I had hundreds of letters from other women of a certain age whose husbands had left them for a younger version, and who sympathised with me and shared their own tragic stories. I was so moved, I answered them all.

- At the same time, so the grapevine informed me, Gaynor’s post was being checked daily before she received it in order to remove upsetting hate-mail. So the underground, anonymous sisterhood expressed its own feelings of empathy for the wife then, as I am doing now.

- By the time Gaynor and I actually met, some five years after the split, at the funeral of Robin’s mother, I certainly had no residual aggressive feelings left. I would have been content to keep my distance, but Robin (with whom I’d had a partial rapprochement) insisted on introducing us. I could hardly believe my own ears as we uttered the social insincerities: “Nice to meet you, Margaret.” “Nice to meet you, Gaynor.”

- The second time we met, tragically, was at Robin’s own funeral, when – thankfully well away from media cameras – we actually embraced. Yet there is too much baggage between us. We shall never be friends. That is out of the question.[25]

A Document by Robin Cook

| Title | Document type | Publication date | Subject(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:The struggle against terrorism cannot be won by military means | article | 8 July 2005 | "War on Terror" Al-Qaeda Osama bin Laden 2005 London bombings | Bin Laden was, though, a product of a monumental miscalculation by western security agencies. Throughout the 80s he was armed by the CIA and funded by the Saudis to wage jihad against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan. Inexplicably, and with disastrous consequences, it never appears to have occurred to Washington that once Russia was out of the way, Bin Laden's organisation would turn its attention to the west. |

References

- ↑ "Robin Cook's resignation speech in the House of Commons"

- ↑ "Ministers turn their backs on marriage"

- ↑ "Marriages England and Wales 1984-2005"

- ↑ "Hansard 23 November 1992"

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/dec/04/bae.armstrade

- ↑ "Robin Cook: 'If the two men are innocent they have nothing to fear from Scottish justice'"

- ↑ "Netanyahu Angrily Cancels Dinner With Visiting Briton"

- ↑ "The sacrifice: why Robin Cook was fired"

- ↑ "Robin Cook's Resignation Speech (in full) - YouTube"

- ↑ "BBC report on Cook's resignation speech"

- ↑ "Robert Finlayson (Robin) Cook, politician and parliamentarian, died on August 6th, aged 59"

- ↑ "Unlike Clare Short, Robin Cook would not be conned"

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 27 January 2004 (pt 37)"

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 9 February 2005 (pt 17)"

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 4 February 2003 (pt 8)"

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 23 February 2005 (pt 1)"

- ↑ "John Kampfner on Robin Cook"

- ↑ "Steve Richards: Progressive causes everywhere will feel the loss of an indispensable politician"

- ↑ "Chris Smith: The House of Commons was Robin Cook's true home"

- ↑ "The struggle against terrorism cannot be won by military means"

- ↑ "Return to Cabinet role for Cook was on the cards"

- ↑ "Gaynor's grief after Cook's mountain fall death"

- ↑ "Mourners' funeral tribute to Cook"

- ↑ "Cook's opposition to Iraq war set in stone"

- ↑ "The first time I met Robin Cook's mistress"

External links

- Guardian Unlimited Politics — Special Report: Robin Cook (1946 - 2005)

- TheyWorkForYou.com — Robin Cook MP

- Cook's "ethical foreign policy" speech, 12 May 1997

- Text of Cook's resignation statement in the House of Commons, 17 March 2003

- Video of Cook's resignation statement in the House of Commons, on the BBC Democracy Live website, 17 March 2003

- The Fruitceller 2 - A huge Video Archive for the Anti-War Movement Contains video of Robin Cooks resignation speech AND the Arms to Iraq Enquiry

Articles

- "Robin Cook's chicken tikka masala speech", Robin Cook, The Guardian, 19 April 2001.

- "Obituary: Remembering Robin Cook One year on" from Labour Party (Ireland)

- "Obituary: Robin Cook" from BBC News

- "Obituary: Robin Cook" from The Guardian

- "Cook resigns from cabinet over Iraq", Matthew Tempest, The Guardian, 17 March 2003

- "The sacrifice", Kamal Ahmed, The Observer, 10 June 2001

- "The struggle against terrorism cannot be won by military means", Robin Cook, The Guardian, 8 July 2005

- "Worse than irrelevant", Robin Cook's last article, The Guardian, 29 July 2005

- "From the Lords to Lebanon, Labour misses Robin Cook", David Clark, The Guardian, 5 August 2006.

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here