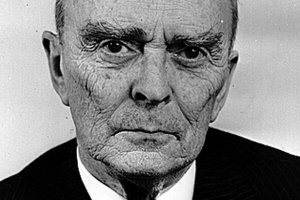

Seán MacBride

| |

| Born | 1904-01-26 Paris, France |

| Died | 1988-01-15 (Age 83) Dublin, Ireland |

| Alma mater | University College Dublin |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Spouse | Catalina |

| Founder of | Amnesty International |

| Party | Clann na Poblachta |

Seán MacBride was an Irish government minister, a prominent international politician and a former Chief of Staff of the IRA.[1] Rising from a domestic Irish political career, he founded or participated in many international organisations of the 20th century, including the United Nations, the Council of Europe and Amnesty International.

Seán MacBride received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1974, the Lenin Peace Prize for 1975–1976 and the UNESCO Silver Medal for Service in 1980.

Contents

Born in Paris

MacBride was born in Paris in 1904, the son of Major John MacBride[2] and Maud Gonne. His first language was French. He remained in Paris until his father's execution after the Easter Rising of 1916, when he was sent to school at Mount St Benedict's, Gorey, County Wexford in Ireland. In 1919, aged 15, he joined the Irish Volunteers and took part in the Irish War of Independence. He opposed the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and was imprisoned by the Irish Free State during the Civil War.[3]

On his release in 1924, MacBride studied law at University College Dublin and resumed his IRA activities. He worked briefly for Éamonn de Valera as his personal secretary, travelling with him to Rome to meet various dignitaries.

In January 1925, on his twenty-first birthday, MacBride married Catalina "Kid" Bulfin, a woman four years his senior who shared his political views. Bulfin was the daughter of the nationalist publisher and travel-writer William Bulfin.

Before returning to Dublin in 1927, where he became the IRA's Director of Intelligence, MacBride worked as a journalist in Paris and London. Soon after his return, he was arrested and charged with the murder of politician Kevin O'Higgins, who had been assassinated near his home in Booterstown, County Dublin. MacBride was able to prove, however, that he was on his way back to Ireland at the time, as he was able to call Unionist turned Cumann na nGaedheal politician Bryan Cooper, whom he had met on the boat home, as a witness. He was then charged with being a subversive and interned in Mountjoy Prison.[4]

Towards the end of the 1920s, after many supporters had left to join Fianna Fáil, some members of the IRA started pushing for a more left-wing agenda. After the IRA Army Council voted down the idea, MacBride launched a new movement, Saor Éire ("Free Ireland"), in 1931. Although it was a non-military organisation, Saor Éire was declared unlawful along with the IRA, Cumann na mBan and nine other bodies. MacBride, meanwhile, became the security services' number-one target.

In 1936, the IRA's chief of staff Moss Twomey was sent to prison for three years. He was replaced by MacBride. At the time, the movement was in a state of disarray, with conflicts between several factions and personalities. Tom Barry was appointed chief of staff to head up a military operation against the British, an action with which MacBride did not agree.

In 1937, MacBride was called to the Irish Bar. He then resigned from the IRA when the Constitution of Ireland was enacted later that year. As a barrister, MacBride frequently defended IRA political prisoners, but was unsuccessful in stopping the execution in 1944 of Charlie Kerins, convicted of killing Garda Detective Dennis O'Brien in 1942. In 1946, during the inquest into the death of Seán McCaughey, MacBride embarrassed the authorities by forcing them to admit that the conditions in Portlaoise Prison were inhumane.[5]

Clann na Poblachta

In 1946, MacBride founded the republican/socialist party Clann na Poblachta. He hoped it would replace Fianna Fáil as Ireland's major political party. In October 1947, he won a seat in Dáil Éireann at a by-election in the Dublin County constituency.[6] On the same day, Patrick Kinane also won the Tipperary by-election for Clann na Poblachta.

However, at the 1948 general election Clann na Poblachta won only ten seats. The party joined with Fine Gael, Labour Party, National Labour Party, Clann na Talmhan and independents to form the First Inter-Party Government with Fine Gael Teachta Dála (TD) John A. Costello as Taoiseach. Richard Mulcahy was the leader of Fine Gael, but MacBride and many other Irish Republicans had never forgiven Mulcahy for his role in carrying out 77 executions under the government of the Irish Free State in the 1920s during the Irish Civil War. To gain the support of Clann na Poblachta, Mulcahy stepped aside in favour of Costello. Two Clann na Poblachta TDs joined the cabinet; MacBride became Minister for External Affairs while Noël Browne became Minister for Health.

MacBride was Minister of External Affairs when the Council of Europe was drafting the European Convention on Human Rights. He served as President of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe from 1949 to 1950 and is credited with being a key force in securing the acceptance of this convention, which was finally signed in Rome on 4 November 1950. In 1950, he was president of the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Council of Europe, and he was vice-president of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC, later OECD) in 1948–51. He was responsible for Ireland not joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).

He was instrumental in the implementation of the Repeal of the External Relations Act and the Declaration of the Republic of Ireland in 1949. On Easter Monday, 18 April 1949, the state left the Commonwealth of Nations.

In 1951, MacBride controversially ordered Noël Browne to resign as a minister over the Mother and Child Scheme after it was attacked by the Irish Catholic hierarchy and the Irish medical establishment. Whatever the merits of the scheme, or of Dr Browne, MacBride concluded in a Cabinet memorandum:

- "Even if, as Catholics, we were prepared to take the responsibility of disregarding [the Hierarchy's] views, which I do not think we can do, it would be politically impossible to do so . . . We are dealing with the considered views of the leaders of the Catholic Church to which the vast majority of our people belong; these views cannot be ignored."[7]

Also in 1951, Clann na Poblachta was reduced to two seats after the general election. MacBride kept his seat and was re-elected again in 1954. Opposing the internment of IRA suspects during the Border Campaign (1956–62), he contested both the 1957 and 1961 general elections but failed to be elected both times. He then retired from politics and continued practising as a barrister. He expressed an interest in running as an independent candidate for the 1983 Irish presidential election, but he did not receive sufficient backing and ultimately did not contest.

International politics

MacBride was a founding member of Amnesty International and served as its International chairman. He was Secretary-General of the International Commission of Jurists from 1963 to 1971. Following this, he was also elected Chair (1968–1974) and later President (1974–1985) of the International Peace Bureau in Geneva. He was Vice-President of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation and President of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.

He drafted the constitution of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU); and also the first constitution of Ghana (the first UK African colony to achieve independence) which lasted for nine years until the coup of 1966.

Some of MacBride's appointments to the United Nations System included:

- United Nations Assistant Secretary-General

- President of the United Nations General Assembly

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

- United Nations Commissioner for Namibia

- President of UNESCO's International Commission for the Study of Communications Problems, which produced the controversial 1980 MacBride report.

Human rights

Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, MacBride worked tirelessly for human rights worldwide. He took an Irish case to the European Court of Human Rights after hundreds of suspected IRA members were interned without trial in the Republic of Ireland in 1958. He was among a group of lawyers who founded Justice — the UK-based human rights and law reform organisation — initially to monitor the show trials after the 1956 Budapest uprising in Hungary, but which later became the UK section of the International Commission of Jurists. He was active in a number of international organisations concerned with human rights, among them the Prisoners of Conscience Appeal Fund (trustee).

In 1973, he was elected by the UN General Assembly to the post of UN Commissioner for Namibia, with the rank of Assistant Secretary-General. The actions of his father John MacBride in leading the Irish Transvaal Brigade (known as MacBride's Brigade) for the Boers against the British Army, in the Second Boer War, gave Seán MacBride a unique access to South Africa's apartheid government. In 1977, he was appointed president of the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, set up by UNESCO. In 1980 he was appointed Chairman of UNESCO.

MacBride's work was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (1974)[8] as a man who "mobilised the conscience of the world in the fight against injustice". He later received the Lenin Peace Prize (1975–76) and the UNESCO Silver Medal for Service (1980).

Nuclear weapons

During the 1980s, he initiated the Appeal by Lawyers against Nuclear War[9] which was jointly sponsored by the International Peace Bureau (IPB) and the International Progress Organisation (IPO). In close co-operation with Francis Boyle and Hans Köchler of the IPO he lobbied the UN General Assembly for a resolution demanding an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the legality of nuclear weapons. The Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons was eventually handed down by the ICJ in 1996.

In 1982, MacBride was chairman of the International Commission to enquire into reported violations of International Law by Israel during its invasion of the Lebanon. The other members were Richard Falk, Kader Asmal, Brian Bercusson, Géraud de la Pradelle, and Stefan Wild. The commission's report, which concluded that "the government of Israel has committed acts of aggression contrary to international law", was published in 1983 under the title Israel in Lebanon.[10]

Religious discrimination

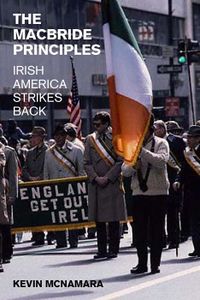

In 1984, MacBride drafted nine affirmative action proposals aimed at eliminating religious discrimination in the employment practices of United States corporations with subsidiaries in Northern Ireland. Published by the Irish National Caucus (INC) in November 1984, the MacBride Principles did not call for quotas, reverse discrimination, divestment (the withdrawal of US Companies from Northern Ireland) or disinvestment (the withdrawal of funds now invested in firms with operations in Northern Ireland). Instead the affirmative action proposals positively encouraged non-discriminatory US investment in Northern Ireland to promote the employment of Roman Catholics.

The INC described the UK's employment practices in Northern Ireland as systematic discrimination against Catholics in almost every way, particularly in employment. All their many protests failed because the effectiveness of protests depended on the good faith of the British government. That good faith was not there. What was needed, therefore, was a campaign that did not depend on the good faith of the British government, but on the fairness of the American people and the leverage of their investment and purchasing dollars.[11]

The British government's reaction to the MacBride Principles was extremely hostile. Using interviews with key personalities involved and hitherto unpublished and inaccessible archives of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Dublin, and papers obtained using the Freedom of Information Acts of the United States and the United Kingdom, the evolution of the MacBride Principles campaign was mapped out in full in a 2010 book by Kevin McNamara, who brought a particular insight through his role as a British Member of Parliament and former Shadow Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.[12]

Died in Dublin

In his later years, MacBride lived in his mother's home, Roebuck House, that served as a meeting place for many years for Irish nationalists, as well as in the Parisian arrondissement where he grew up with his mother, and enjoyed strolling along boyhood paths. He maintained a soft-spoken, unassuming demeanor despite his fame. While strolling through the Centre Pompidou Museum in 1979, and happening upon an exhibit for Amnesty International, he whispered to a colleague "Amnesty, you know, was one of my children."

Seán MacBride died in Dublin on 15 January 1988, eleven days before his 84th birthday. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, among Irish patriots, in a simple grave with his mother and wife who died in 1976.

MacBride Peace Prize

Established four years after his death, the MacBride Peace Prize is awarded annually by the International Peace Bureau (IPB) to a person or organisation that has done outstanding work for peace, disarmament and/or human rights. The IPB announced that Jeremy Corbyn is one of three recipients of the MacBride Peace Prize in 2017:

- "Jeremy Corbyn is awarded – for his sustained and powerful political work for disarmament and peace. As an active member, vice-chair and now vice-president of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the UK he has for many years worked to further the political message of nuclear disarmament. As the past chair of the Stop the War Coalition in the UK he has worked for peace and alternatives to war. He has ceaselessly stood by the principles, which he has held for so long, to ensure true security and well-being for all – for his constituents, for the citizens of the UK and for the people of the world."[13]

Career summary

- 1946–1965 Leader of Clann na Poblachta

- 1947–1958 Member of Dáil Éireann

- 1948–1951 Minister for External Affairs of Ireland in Inter-Party Government

- 1948–1951 Vice-President of the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC)

- 1950 President, Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe

- 1954 Offered but declined, Ministerial office in Irish Government

- 1963–1971 Secretary-General, International Commission of Jurists

- 1966 Consultant to the Pontifical Commission on Justice and Peace

- 1961–1975 chairman Amnesty International Executive

- 1968–1974 Chairman of the Executive International Peace Bureau

- 1975–1985 President of the Executive International Peace Bureau

- 1968–1974 chairman Special Committee of International NGOs on Human Rights (Geneva)

- 1973 vice-chairman, Congress of World Peace Forces (Moscow, October 1973)

- 1973 Vice-President, World Federation of United Nations Associations

- 1973–1977 Elected by the General Assembly of the United Nations to the post of United Nations Commissioner for Namibia with rank of Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations

- 1977–1980 chairman, Commission on International Communication for UNESCO

- 1982 Chairman of the International Commission to enquire into reported violations of International Law by Israel during its invasion of the Lebanon

Further reading

- Keane, Elizabeth (2006). An Irish Statesman and Revolutionary: The Nationalist and Internationalist Politics of Seán MacBride. Tauris.

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:Has the media ignored good news about Jeremy Corbyn | Blog post | 11 December 2017 | Patrick Worrall | No-platforming Jeremy Corbyn: Tories and Unionists have a visceral hate of Seán MacBride |

References

- ↑ http://www.oireachtas.ie/members-hist/default.asp?housetype=0&HouseNum=12&MemberID=671&ConstID=77

- ↑ Saturday Evening Post; 23 April 1949, Vol. 221 Issue 43, pp. 31–174, 5p

- ↑ Jordan, Anthony J. (1993). Seán MacBride: A Biography. Dublin: Blackwater Press. pp. 26–35. ISBN 0-86121-453-6.

- ↑ Jordan (1993), p. 47.

- ↑ Hanley, Brian (2010). The IRA: A Documentary History 1916–2005. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 122. ISBN 0717148130.

- ↑ http://www.electionsireland.org/candidate.cfm?ID=2263

- ↑ Ronan Fanning (6 December 2009) "The age of our craven deference is finally over", The Independent

- ↑ United Nations Chronicle, Sep95, Vol. 32 Issue 3, p. 14, 2/5p, 1c; (AN 9511075547)

- ↑ "Appeal by Lawyers against Nuclear War". I-p-o.org. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ MacBride, Seán; A. K. Asmal; B. Bercusson; R. A. Falk; G. de la Pradelle; S. Wild (1983). Israel in Lebanon: The Report of International Commission to enquire into reported violations of International Law by Israel during its invasion of the Lebanon. London: Ithaca Press. p. 191. ISBN 0-903729-96-2.

- ↑ "The MacBride Principles – The Essence"

- ↑ "The MacBride Principles: Irish America Strikes Back"

- ↑ "MacBride Peace Prize to Jeremy Corbyn"

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here