Difference between revisions of "Carl Burckhardt"

m |

(unstub) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

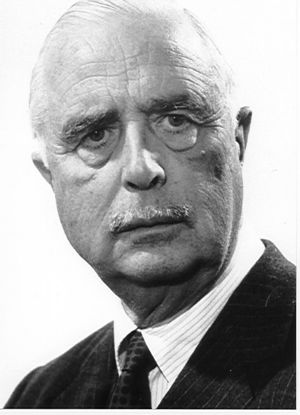

|image=Carl Burckhardt.jpg | |image=Carl Burckhardt.jpg | ||

|nationality=Swiss | |nationality=Swiss | ||

| + | |interests=ratlines | ||

| + | |alma_mater=University of Basel, University of Zürich, University of Munich, University of Göttingen | ||

|birth_date=September 10, 1891 | |birth_date=September 10, 1891 | ||

|birth_place=Basel, Switzerland | |birth_place=Basel, Switzerland | ||

| Line 10: | Line 12: | ||

|death_place=Vinzel, Switzerland | |death_place=Vinzel, Switzerland | ||

|constitutes=diplomat, historian | |constitutes=diplomat, historian | ||

| − | |description= | + | |description=President of the [[International Committee of the Red Cross]] (1945–48), where he assisted Germans wanted for war crimes [[ratlines|escape to South America]]. [[Bilderberg/1955 September|September 1955]] and [[Bilderberg/1956|1956 Bilderberg meeting]]s. |

| + | |relatives=Gonzague de Reynold | ||

| + | |employment={{job | ||

| + | |title=President of the International Committee of the Red Cross | ||

| + | |start=1945 | ||

| + | |end=1948 | ||

| + | |description=Organized [[ratlines]] for fleeing Nazis | ||

| + | }}{{job | ||

| + | |title=Switzerland/Ambassador/France | ||

| + | |start=1945 | ||

| + | |end=1949 | ||

| + | }}{{job | ||

| + | |title=Professor | ||

| + | |start=1932 | ||

| + | |end=1937 | ||

| + | |employer=Graduate Institute of International Studies | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Carl Jacob Burckhardt''' was a Swiss historian and | + | }}''Not to be confused with the 19th-century historian [[Jacob Burckhardt (historian)|Jacob Burckhardt]]'' |

| − | == | + | '''Carl Jacob Burckhardt''' was a [[Switzerland|Swiss]] [[diplomat]] and [[historian]]. His career alternated between periods of academic historical research and diplomatic postings; the most prominent of the latter were [[League of Nations]] High Commissioner for the [[Free City of Danzig]] (1937–39) and President of the [[International Committee of the Red Cross]] (1945–48), where he assisted Germans wanted for war crimes escape to [[South America]]. |

| − | He was High Commissioner of the League of Nations for Danzig. | + | |

| + | He attended the [[Bilderberg/1955 September|September 1955]] and [[Bilderberg/1956|1956 Bilderberg meeting]]s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Biography== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Burckhardt was born in [[Basel]] to Carl Christoph Burckhardt, a member of the patrician [[Burckhardt]] family, and attended [[gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]] in Basel and [[Glarisegg]] (in [[Steckborn]]). He subsequently studied at the universities of Basel, [[Zürich]], [[Munich]], and [[Göttingen]], being particularly influenced by professors [[Ernst Gagliardi]] and [[Heinrich Wölfflin]]. Even when he was still a student, there was a rumor in [[Zurich]] that his sister had written her brother's doctoral dissertation.<ref>https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baselbieter_Heimatbl%C3%A4tter</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | He gained his first diplomatic experience in the Swiss legation in [[Austria]] from 1918 to 1922, a chaotic period following the collapse of [[Austria-Hungary]]. While there, he became acquainted with [[Hugo von Hofmannsthal]]. Burckhardt earned his doctorate in 1922, and then accepted an appointment with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which posted him to [[Asia Minor]], where he assisted in the [[Population exchange between Greece and Turkey|resettlement of Greeks expelled from Turkey]] following Greece's [[Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)|1922 defeat]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He subsequently returned to Switzerland, where he married Elisabeth de Reynold (a daughter of [[Gonzague de Reynold]]) and pursued an academic career. He was appointed [[Privatdozent]] at the [[University of Zurich]] in 1927, and in 1929 was appointed [[extraordinary professor]] of contemporary history. From 1932 to 1937 he was [[ordinary professor]] at the recently created [[Graduate Institute of International Studies]] in [[Geneva]]. While there, he published in 1935 the first volume of his comprehensive biography of [[Cardinal Richelieu]], which would eventually be completed by the publication of the 4th volume in 1967. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He returned to a diplomatic career in 1937, serving as the final League of Nations High Commissioner for the [[Free City of Danzig]] from 1937 to 1939. In that position, he aimed to maintain the international status of Danzig guaranteed by the League of Nations, which brought him into contact with a number of prominent [[Nazis]] as he attempted to stave off increasing German demands. The mission eventually ended unsuccessfully with the [[Invasion of Poland (1939)|invasion of Poland]] and German annexation of Danzig. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following this period as High Commissioner, he returned to his professorship in Geneva for the rest of [[World War II]] (1939–1945). While in that position, he was also active in a leading role in the ICRC, traveling to Germany several times to negotiate for better treatment of civilians and prisoners, in part using the contacts gained during his two years as High Commissioner in Danzig. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Involvement with Nazism=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the war, he became President of the ICRC, serving from 1945 to 1948. Organizationally, he increased the integration of the international Red Cross institutions and the national [[Red Cross Society|Red Cross Societies]]. Politically, his term was controversial as he maintained the ICRC's existing policy of strict neutrality in international disputes, which led to the ICRC refusing to condemn the Nazis as their atrocities came to light officially. His strong [[anticommunism]] led him to considering Nazism the lesser evil.<ref name=":0" /> He meanwhile simultaneously served from 1945 to 1949 as the Swiss envoy in [[Paris]]. He opposed the [[Nuremberg trials]], calling them “Jewish revenge.”<ref name=":0">https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-red-cross-and-the-holocaust-1500417644</ref> Under his watch, the ICRC provided documents that helped many high-level Nazis, including [[Adolf Eichmann]] and [[Josef Mengele]], escape Europe and evade justice for their war crimes in World War II.<ref name=":0" /><ref>http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/may/25/nazis-escaped-on-red-cross-documents</ref><ref>https://www.dw.com/en/the-ratlines-what-did-the-vatican-know-about-nazi-escape-routes/a-52555068</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Red Cross' stance during the war did not fully come to light until it opened its archives from the period in 1994.{{sfn|Rothkirchen|2006|p=303}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | After 1949, he returned to his academic career, publishing a number of books on history over the next several decades. In 1954, he was awarded the [[Peace Prize of the German Book Trade]]. He died in 1974 in [[Vinzel]]. His wife died in 1989. | ||

{{SMWDocs}} | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{PageCredit |

| + | |site=Wikipedia | ||

| + | |date=04.04.2022 | ||

| + | |url=https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Jacob_Burckhardt | ||

| + | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 08:51, 2 May 2022

(diplomat, historian) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Born | September 10, 1891 Basel, Switzerland | |||||||||||

| Died | March 3, 1974 (Age 82) Vinzel, Switzerland | |||||||||||

| Nationality | Swiss | |||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Basel, University of Zürich, University of Munich, University of Göttingen | |||||||||||

| Interests | ratlines | |||||||||||

| Relatives | Gonzague de Reynold | |||||||||||

President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (1945–48), where he assisted Germans wanted for war crimes escape to South America. September 1955 and 1956 Bilderberg meetings.

| ||||||||||||

Not to be confused with the 19th-century historian Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Burckhardt was a Swiss diplomat and historian. His career alternated between periods of academic historical research and diplomatic postings; the most prominent of the latter were League of Nations High Commissioner for the Free City of Danzig (1937–39) and President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (1945–48), where he assisted Germans wanted for war crimes escape to South America.

He attended the September 1955 and 1956 Bilderberg meetings.

Biography

Burckhardt was born in Basel to Carl Christoph Burckhardt, a member of the patrician Burckhardt family, and attended gymnasium in Basel and Glarisegg (in Steckborn). He subsequently studied at the universities of Basel, Zürich, Munich, and Göttingen, being particularly influenced by professors Ernst Gagliardi and Heinrich Wölfflin. Even when he was still a student, there was a rumor in Zurich that his sister had written her brother's doctoral dissertation.[1]

He gained his first diplomatic experience in the Swiss legation in Austria from 1918 to 1922, a chaotic period following the collapse of Austria-Hungary. While there, he became acquainted with Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Burckhardt earned his doctorate in 1922, and then accepted an appointment with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which posted him to Asia Minor, where he assisted in the resettlement of Greeks expelled from Turkey following Greece's 1922 defeat.

He subsequently returned to Switzerland, where he married Elisabeth de Reynold (a daughter of Gonzague de Reynold) and pursued an academic career. He was appointed Privatdozent at the University of Zurich in 1927, and in 1929 was appointed extraordinary professor of contemporary history. From 1932 to 1937 he was ordinary professor at the recently created Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva. While there, he published in 1935 the first volume of his comprehensive biography of Cardinal Richelieu, which would eventually be completed by the publication of the 4th volume in 1967.

He returned to a diplomatic career in 1937, serving as the final League of Nations High Commissioner for the Free City of Danzig from 1937 to 1939. In that position, he aimed to maintain the international status of Danzig guaranteed by the League of Nations, which brought him into contact with a number of prominent Nazis as he attempted to stave off increasing German demands. The mission eventually ended unsuccessfully with the invasion of Poland and German annexation of Danzig.

Following this period as High Commissioner, he returned to his professorship in Geneva for the rest of World War II (1939–1945). While in that position, he was also active in a leading role in the ICRC, traveling to Germany several times to negotiate for better treatment of civilians and prisoners, in part using the contacts gained during his two years as High Commissioner in Danzig.

Involvement with Nazism

After the war, he became President of the ICRC, serving from 1945 to 1948. Organizationally, he increased the integration of the international Red Cross institutions and the national Red Cross Societies. Politically, his term was controversial as he maintained the ICRC's existing policy of strict neutrality in international disputes, which led to the ICRC refusing to condemn the Nazis as their atrocities came to light officially. His strong anticommunism led him to considering Nazism the lesser evil.[2] He meanwhile simultaneously served from 1945 to 1949 as the Swiss envoy in Paris. He opposed the Nuremberg trials, calling them “Jewish revenge.”[2] Under his watch, the ICRC provided documents that helped many high-level Nazis, including Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele, escape Europe and evade justice for their war crimes in World War II.[2][3][4]

The Red Cross' stance during the war did not fully come to light until it opened its archives from the period in 1994.[5]

After 1949, he returned to his academic career, publishing a number of books on history over the next several decades. In 1954, he was awarded the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. He died in 1974 in Vinzel. His wife died in 1989.

Events Participated in

| Event | Start | End | Location(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilderberg/1955 September | 23 September 1955 | 25 September 1955 | Germany Bavaria Garmisch-Partenkirchen | The third Bilderberg, in West Germany. The subject of a report by Der Spiegel which inspired a heavy blackout of subsequent meetings. |

| Bilderberg/1956 | 11 May 1956 | 13 May 1956 | Denmark Fredensborg | The 4th Bilderberg meeting, with 147 guests, in contrast to the generally smaller meetings of the 1950s. Has two Bilderberg meetings in the years before and after |

References

- ↑ https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baselbieter_Heimatbl%C3%A4tter

- ↑ a b c https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-red-cross-and-the-holocaust-1500417644

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/may/25/nazis-escaped-on-red-cross-documents

- ↑ https://www.dw.com/en/the-ratlines-what-did-the-vatican-know-about-nazi-escape-routes/a-52555068

- ↑ Rothkirchen 2006, p. 303.

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here