İsmet İnönü

(soldier, politician) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Born | Mustafa İsmet 1884-09-24 İzmir, Aidin Vilayet, Ottoman Empire | |||||||||

| Died | 1973-12-25 (Age 89) Ankara, Turkey | |||||||||

| Nationality | Turkish | |||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | |||||||||

| Children | Erdal İnönü | |||||||||

| Spouse | Mevhibe İnönü | |||||||||

| Party | Republican People's Party | |||||||||

Turkish PM intermittently from 1923 to 1965

| ||||||||||

Mustafa İsmet İnönü was a Turkish general[1] and statesman, who served as the second President of Turkey from 11 November 1938 to 22 May 1950, when his Republican People's Party was defeated in Turkey's second free elections. He was also the first Chief of the General Staff from 1922 to 1924, and as the first Prime Minister after the declaration of the Republic, serving three terms: from 1923 to 1924, 1925 to 1937, and 1961 to 1965. As President, he was granted the official title of "Millî Şef" (National Chief).[2]

When the 1934 Surname Law was adopted, Mustafa Kemal gave him a surname taken from İnönü, where he commanded the forces of the Turkish Army as the Minister of the Chief of the General Staff during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922.

Contents

Chief negotiator in Mudanya and Lausanne

After the War of Independence was won, İsmet Pasha was appointed as the chief negotiator of the Turkish delegation, both for the Armistice of Mudanya and for the Treaty of Lausanne.

The Lausanne conference convened in late 1922 to settle the terms of a new treaty that would take the place of the Treaty of Sèvres. Inönü became famous for his stubborn resolve in determining the position of Ankara as the legitimate, sovereign government of Turkey. After delivering his position, Inönü turned off his hearing aid during the speeches of British foreign secretary Lord Curzon. When Curzon had finished, Inönü reiterated his position as if Curzon had never said a word.[3]

Single-party period

Prime Minister

İnönü later served as the Prime Minister of Turkey for several terms, maintaining the system that Mustafa Kemal had put in place. He acted after every major crisis (such as the Sheikh Said rebellion or the attempted assassination in İzmir against Mustafa Kemal) to restore peace in the country. In October 1923 he suggested to make Ankara the capital of Turkey, which successively was approved by the parliament.[4] He shortly stepped down as prime minister between He replaced prime minister Fethi Okyar at a time the seriousness of the situation around the Sheikh Said Rebellion was realized by the Turkish Government in spring 1925.[5] While dealing with the Sheikh Said revolt he proclaimed a Turkish nationalist policy and encouraged the turkification of the non-Turkish population.[6] In September 1925, following the suppression of the Sheikh Said rebellion, he presided over the Reform Council for the East which prepared the Report for Reform in the East, which recommended to impede an establishment of a Kurdish elite, to forbid non-Turkish languages and the creation of regional administrative units called Inspectorates-General, which were to be governed with martial law.[7] Following this report, three Inspectorates-Generals were established in the Kurdish areas comprising several provinces.[8]

Statism in economy

He tried to manage the economy with heavy-handed government intervention, especially after the 1929 economic crisis, by implementing an economic plan inspired by the Five Year Plan of the Soviet Union. In doing so, he took much private property under government control. Due to his efforts, to this day, more than 70% of land in Turkey is still owned by the state.

Desiring a more liberal economic system, Atatürk dissolved the government of İnönü[9] and appointed Celâl Bayar, the founder of the first Turkish commercial bank Türkiye İş Bankası, as Prime Minister.

"National Chief" period

President

After the death of Atatürk on 10 November 1938,[10] İnönü was viewed as the most appropriate candidate to succeed him, and was elected the second President of the Republic of Turkey. He enjoyed the official title of "Millî Şef", i.e. "National Chief".

World War II broke out in the first year of his presidency, and both the Allies and the Axis pressured İnönü to bring Turkey into the war on their side.[11] The Germans sent Franz von Papen to Ankara in April 1939 while the British sent Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen and the French René Massigli. On 23 April 1939, Turkish Foreign Minister Şükrü Saracoğlu told Knatchbull-Hugessen of his nation's fears of Italian claims of the Mediterranean as Mare Nostrum and German control of the Balkans, and suggested an Anglo-Soviet-Turkish alliance as the best way of countering the Axis.[12] In May 1939, during the visit of Maxime Weygand to Turkey, İnönü told the French Ambassador René Massigli that he believed that the best way of stopping Germany was an alliance of Turkey, the Soviet Union, France and Britain; that if such an alliance came into being, the Turks would allow Soviet ground and air forces onto their soil; and that he wanted a major programme of French military aid to modernize the Turkish armed forces.[13]

The signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939 drew Turkey away from the Allies; the Turks always believed that it was essential to have the Soviet Union as an ally to counter Germany, and thus the signing of the German-Soviet pact undercut completely the assumptions behind Turkish security policy.[14] With the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, İnönü chose to be neutral in World War II as taking on Germany and the Soviet Union at the same time would be too much for Turkey, through he signed a treaty of alliance with Britain and France on 19 October 1939.[15] It was only with France's defeat in June 1940 that İnönü abandoned the pro-Allied neutrality that he had followed since the beginning of the war.[15]

A major embarrassment for the Turks occurred in July 1940 when the Germans captured and published documents from the Quai d'Orsay in Paris showing the Turks were aware of Operation Pike—as the Anglo-French plan in the winter of 1939–40 to bomb the oil fields in the Soviet Union from Turkey was codenamed—which was intended by Berlin to worsen relations between Ankara and Moscow.[16] In turn, worsening relations between the Soviet Union and Turkey were intended to drive Turkey into the arms of the Reich.[15] After the publication of the French documents relating to Operation Pike, İnönü had to sign an economic treaty with Germany that placed Turkey within the German economic sphere of influence, but İnönü would go no further towards the Axis.[17]

In the first half of 1941, Germany which was intent upon invading the Soviet Union went out of its way to improve relations with Turkey as the Reich hoped for a benevolent Turkish neutrality when the German-Soviet war began.[18] At the same time, the British had great hopes in the spring of 1941 when they dispatched an expeditionary force to Greece that İnönü could be persuaded to enter the war on the Allied side as the British leadership had high hopes of creating a Balkan front that would tie down German forces, and which thus led a major British diplomatic offensive with the Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden visiting Ankara several times to meet with İnönü.[19] İnönü always told Eden that the Turks would not join the British forces in Greece, and the Turks would only enter the war if Germany attacked Turkey.[20] For his part, Papen offered İnönü parts of Greece if Turkey were to enter the war on the Axis side, an offer İnönü declined.[20] In May 1941 when the Germans dispatched an expeditionary force to Iraq to fight against the British, İnönü refused Papen's request that the German forces be allowed transit rights to Iraq.[21]

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill travelled to Ankara on 30 January 1943 for a conference with President İnönu, to urge Turkey's entry into the war on the allied side.[22] Churchill met secretly with İnönü in January 1943, inside a railroad car at the Yenice Station near Adana. However, by December 4–6, 1943, İnönü felt confident enough about the outcome of the war, that he met openly with Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill at the Second Cairo Conference. Until 1941, both Roosevelt and Churchill had thought that Turkey's continuing neutrality would serve the interests of the Allies by blocking the Axis from reaching the strategic oil reserves of the Middle East. But the early victories of the Axis up to the end of 1942 caused Roosevelt and Churchill to re-evaluate a possible Turkish participation in the war on the side of the Allies. Turkey had maintained a decently-sized Army and Air Force throughout the war, and Churchill wanted the Turks to open a new front in the Balkans. Roosevelt, on the other hand, still believed that a Turkish attack would be too risky, and an eventual Turkish failure would have disastrous effects for the Allies.

İnönü knew very well the hardships which his country had suffered during decades of incessant war between 1908 and 1922 and was determined to keep Turkey out of another war as long as he could. The young Turkish Republic was still re-building, recovering from the losses due to earlier wars, and lacked any modern weapons and the infrastructure to enter a war to be fought along and possibly within its borders. İnönü based his neutrality policy during the Second World War on the premise that Western Allies and the Soviet Union would sooner or later have a falling out after the war.[23] Thus, İnönu wanted assurances on financial and military aid for Turkey, as well as a guarantee that the United States and the United Kingdom would stand beside Turkey in the event of a Soviet invasion of the Turkish Straits after the war. In August 1944 İnönü broke off diplomatic relations with Germany and on 5 January 1945, İnönü severed diplomatic relations with Japan.[24] Shortly afterwards, İnönü allowed Allied shipping to use the Turkish straits to send supplies to the Soviet Union and on 25 February 1945 he declared war on Germany and Japan.[21]

The post-war tensions and arguments surrounding the Turkish Straits, when the Soviet Union demanded Turkey to allow Soviet shipping to flow freely through the Turkish Straits (something which was barred in WW2) would come to be known as the Turkish Straits crisis. The fear of Soviet invasion and Joseph Stalin's unconcealed desire for Soviet military bases in the Turkish Straits[23] eventually caused Turkey to give up its principle of neutrality in foreign relations and join NATO in February 1952.[25]

Multi-party period

Under international pressure to transform the country to a democratic state, İnönü presided over the infamous 1946 elections, where voting was carried out under the gaze of onlookers who could determine which voters had voted for which parties, and where secrecy prevailed as to the subsequent counting of votes. Free and fair national elections had to wait till 1950, and on that occasion İnönü's government was defeated.

In the 1950 campaign, the leading figures of the opposition Democrat Party used the following slogan: "Geldi İsmet, kesildi kısmet" ("Ismet arrived, [our] fortune left" ). İnönü presided over the peaceful transfer of power to the Democratic Party of Celâl Bayar and Adnan Menderes. For ten years he served as the leader of the opposition before returning to power as Prime Minister after the 1961 election, held after the military coup-d'etat in 1960.

Even though the pro-Menderes opposition was forbidden to contest the 1961 election (most of its leaders who were still alive were in prison), İnönü's forces still did not gain enough seats in the legislature to win a majority. Therefore, they had to form coalition governments until 1965. İnönü lost both the 1965 and 1969 general elections to a much younger man, Süleyman Demirel, but he remained leader of the party till 1972, whereupon he was defeated by leadership rival Bülent Ecevit. In 1964 İnönü renounced the Greco-Turkish Treaty of Friendship of 1930 and took actions against the Greek minority.[26][27] Following the Turkish Government also strictly enforced a long‐overlooked law barring Greek nationals from 30 professions and occupations, for example Greeks could not be doctors, nurses, architects, shoemakers, tailors, plumbers, cabaret singers, ironsmiths, cooks, tourist guides, etc. and 50,000 more Greeks were deported. These actions were done, because of the growing anti-Greek sentiment in Turkey, after the Cyprus issue became a reality.[28]

In a meeting in Bursa for the 1969 general elections, a young man yelled at him; "You let us go without food!" by implying not joining World War II. İnönü replied him by saying "Yes, I let you go without food, but I did not let you become fatherless" by implying death of millions of people from the both sides of World War II.[29]

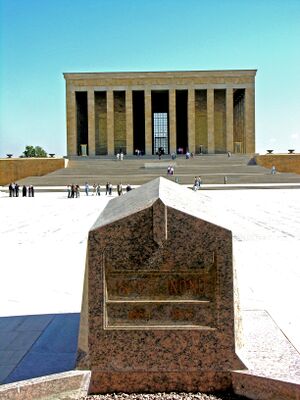

He died on 25 December 1973 of a heart attack, at the age of 89, and was interred opposite to Atatürk's mausoleum at Anıtkabir in Ankara.

References

- ↑ http://www.tsk.tr/1_TSK_HAKKINDA/1_2_Genelkurmay_Baskanlari/konular/ismet_inonu.htm T

- ↑ Howard, Douglas Arthur (2001). The History of Turkey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 109.

- ↑ Cleveland, William L., and Martin P. Bunton. A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder: Westview, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Feroz, Ahmad (November 2002). The Making of Modern Turkey. Routledge. pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Dag, Rahman (23 June 2017). Ideological Roots of the Conflict between Pro-Kurdish and Pro-Islamic Parties in Turkey. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 33.

- ↑ Dag, Rahman (23 June 2017). Ideological Roots of the Conflict between Pro-Kurdish and Pro-Islamic Parties in Turkey. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Yadirgi, Veli (3 August 2017). The Political Economy of the Kurds of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Jongerden, Joost (28 May 2007). The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds: An Analysis of Spatial Policies, Modernity and War. BRILL. p. 53.

- ↑ Lord Kinross, Atatürk: A biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Modern Turkey (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1965) p. 449.

- ↑ Nicole Pope and Hugh Pope, Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey (New York: The Overlook Press, 2004) p. 68.

- ↑ Nicole Pope and Hugh Pope, Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey, p. 75.

- ↑ Watt, D.C. How War Came : The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938–1939 ,London: Heinemann, 1989 page 278

- ↑ Watt, D.C. How War Came : The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938–1939, London: Heinemann, 1989 page 282

- ↑ Watt, D.C. How War Came : The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938–1939, London: Heinemann, 1989 page 310.

- ↑ a b c Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 page 78

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 page 970

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 page 78

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 pages 196-197.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 pages 216-216.

- ↑ a b Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 page 219.

- ↑ a b Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 page 226.

- ↑ Andrew Mango, The Turks Today, (New York: The Overlook Press, 2004) p. 36.

- ↑ a b Andrew Mango, The Turks Today, p. 37.

- ↑ Weinberg, Gerhard A World In Arms, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 page 809.

- ↑ Andrew Mango, The Turks Today, p. 47.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/1964/08/09/archives/turks-expelling-istanbul-greeks-communitys-plight-worsens-during.html

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=mQRtAAAAQBAJ

- ↑ https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2017/12/14/why-turkey-and-greece-cannot-reconcile

- ↑ https://www.sozcu.com.tr/2017/yazarlar/rahmi-turan/ama-sizi-babasiz-birakmadim-1637537/