Document:HSBC and the sham of Guardian’s Scott Trust

| Britain, we are told, is privileged to have two “liberal” media outlets, the BBC and Guardian, that are seen either as neutral or as a leftwing counterbalance to the rightwing agenda of the rest of the media. Here are three illuminating articles and a short video that should help to dispel any such illusions. |

Subjects: Scott Trust Ltd, The Guardian, Glenn Greenwald, BBC, Seumas Milne, Alasdair Milne, Nafeez Ahmed, HSBC, Swiss Leaks

Source: Jonathan Cook Blog (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

When I and others accuse the British media of systematic and consistent bias in favour of corporate power, and point out that the media is structurally part of that system of corporate power, we typically receive emails from readers arguing that not all parts of the media are subject to such pressures. Britain, we are told, is privileged to have two “liberal” media outlets, the BBC and Guardian, that are seen either as neutral or as a leftwing counterbalance to the rightwing agenda of the rest of the media.

Occasionally, it is also claimed that Britain’s media regulator, Ofcom, is there to prevent bias, ensuring that minimum standards of objectivity are maintained in news coverage.

Here are three illuminating articles and a short video that should help to dispel any such illusions about a healthy and diverse British media. Rather, the media in the UK is embedded in the corporate world, and therefore incapable of fulfilling its self-declared role as watchdog against abuses by the powerful.

The first article, by Glenn Greenwald, shows how Ofcom is just another tool of the British state to intimidate and exclude any voices, such as broadcasters RT and Iran’s PressTV, that might provide a narrative that challenges the official London-Washington consensus on world events.[1] Ofcom has just announced yet another investigation of RT for “bias”. RT is not even allowed to discuss the case while it is being investigated. Greenwald points out:

- All of this underscores the propagandistic purpose of touting “media objectivity” versus “bias.” The former simply does not exist. Revealingly, it is British journalists themselves who are most vocal in demanding that Her Majesty’s Government bar RT from broadcasting on “bias” grounds: fathom how authoritarian a society must be if it gets its journalists to play the leading role in demanding that the state ban (or imprison) journalists it dislikes. So notably, the most vocal among the anti-RT crowd on the ground that it spreads lies and propaganda — such as Nick Cohen [of the Observer] and Oliver Kamm [of the London Times] — were also the most aggressive peddlers of the pro-UK-government conspiracy theories and lies that led to the Iraq War. …

This is about nothing more than ensuring that Western citizens are not exposed to the side of The Enemy. … Western countries love to depict citizens of their long list of adversaries as being propagandized — whether it be China, Iran, Russia, North Korea, ISIS, Al Qaeda, Syria, Venezuela, Ecuador, etc. etc. — even as they themselves work in all sorts of ways to ban their own citizens from exposure to those adversaries’ views.

The second, by Seumas Milne, reviews a new book offering a history of the BBC through the difficult years when Margaret Thatcher waged a relentless assault against its supposed left-wing politics.[2] Milne notes that in the years before Thatcher’s interference the BBC’s programming was in some ways more liberal than it is today, but even so:

The corporation was always an establishment institution, deeply embedded in the security state and subject to direct government control in an emergency. The sexism at the BBC, as Seaton recounts, was appalling, as in many other workplaces, and ethnic diversity non-existent. Around 40% of the staff were vetted by MI5: those who failed the “political reliability” test, often for the mildest of radical connections, were blacklisted – their personnel files marked with the symbol of a Christmas tree. To give a flavour of the relationship, one broadcaster still well-known today had to be brought home from a foreign posting in the 1980s after BBC management became alarmed that his relationship with MI6 was becoming too overt.

Thatcher lost no time in sacking Alasdair Milne, the BBC’s director-general, Milne’s father, and bringing into the BBC the new corporate boardroom culture she was cultivating throughout the economy. With it, the BBC became even more politically obedient than it already was:

- Once the government had demonstrated it could not only manipulate the licence fee to ensure BBC compliance, but summarily dispatch its leadership at barely one remove, what BBC director-general or chair would do anything but bend the knee or jump ship? That is what happened in 2004, after a report by a tame judge into the death of the weapons expert David Kelly and BBC reporting of government deceit over the Iraq war led not to the fall of ministers or officials – but the resignation of the chairman and director-general of the BBC. …

Two decades on, in a symbolic mark of its creeping corporate capture, the latest BBC trust chair, Rona Fairhead, has become embroiled in the tax dodging scandal that has engulfed HSBC, of which she is also a non-executive director.

Finally, Nafeez Ahmed, an investigative reporter fired by the Guardian for his work exposing the connection between Israel’s attacks on Gaza and its interests in Gaza’s natural resources, exposes the sham of the Guardian’s Scott Trust.

In the first 12 mins of the following video, he talks to RT’s Going Underground about the Trust and the reasons for his sacking – maybe this interview will offer Ofcom yet more grounds for banning RT from Britain’s airwaves.[3]

Even more important is his latest lengthy, wide-ranging and crowd-funded investigation into how the HSBC bank and the City are deeply implicated in money-laundering the proceeds of globalised crime, and how that same financial sector has captured not only Britain’s political elites but also the entire British media.[4] Yes, the entire media, including the Guardian, which has been lauded for its recent revelations about the corrupt practices of HSBC’s Swiss arm.

Ahmed points out, however, that the Guardian has very much pulled its punches on fraudulent practices by HSBC in the UK. A whistleblower, Nicholas Wilson, has spent years trying to publicise the overcharging of British shoppers, some 600,000 of them, of quite astounding sums totalling £1 billion in debt collection charges through their credit cards. HSBC has been at the heart of this mass fraud.

According to Ahmed, almost every major British investigative team, including the Guardian, has got close to publication and then spiked the story for unexplained reasons. The regulatory authorities admit that HSBC has lied about its practices and that there are grounds for suspecting that fraud on an enormous scale has occurred but they have refused to investigate further, saying such action would be “disproportionate”. The reason, he argues, is that:

- London, even more than Wall Street, is the world’s finance capital, harbouring most of the global economy’s international transactions, and therefore holding 400% more money than Britain’s entire GDP. A significant quantity of this money — “many hundreds of billions of pounds” worth — is from the criminal economy and laundered through UK banks and their subsidiaries. As financial sector campaigner Joel Benjamin said:

- “What the British government cannot tell the public is that the current growth model for the UK economy revolves around the endorsement and protection of financial sector fraud.”

The exposure of HSBC’s fraud in Britain could fundamentally jeopardise both the bank’s domestic and US operations.

In other words, politically and economically, HSBC is too big to fail. And for that reason it is well-protected by the corporate media. The HSBC has done more than any other bank to ensure its friends are embedded in the very senior echelons of the political and media class. Note, as Milne observes above, that the BBC Trust is headed by Rona Fairhead. Here’s Fairhead’s CV, according to Ahmed:

- Fairhead is currently chair of HSBC’s North America Holdings, and was chair of the audit and risk committee when HSBC was fined by US authorities for money-laundering. Some of the fraud exposed in the Swiss Leaks occurred during her watch on the committee. Before her government nomination to the BBC, Fairhead was appointed a British Business Ambassador by Prime Minister David Cameron. Prior to that, she had been a non-executive board director for the UK Cabinet Office under the coalition government.

The Guardian is no less in bed with HSBC, as Ahmed details. Recently, Peter Oborne, formerly of Britain’s Daily Telegraph, revealed that his newspaper spiked HSBC stories to avoid losing ad revenue. The Guardian is even more dependent on income from HSBC than the Telegraph.

During the Treasury Select Committee meeting on 15th February, it emerged that the newspaper that styles itself as the world’s “leading liberal voice” happens to be the biggest recipient of HSBC advertising revenue: bigger even than the Telegraph. … User growth permitted a dramatic increase in advertising revenues: :“Revenues from US operations more than doubled on the previous 12-month period, reflecting advertising demand and sponsorship deals with partners such as HSBC, Netflix and Airbnb.”

According to the Guardian’s supporters, the benevolent Scott Trust acts as a buffer against commercial pressures, guaranteeing the Guardian’s editorial independence and its liberal-left credentials. Ahmed throws cold water on that theory:

- The Guardian is not owned by a trust at all. In 2008, “the trust was replaced with a limited company” that was accordingly re-named “The Scott Trust Limited.” Though not a trust at all, but simply a profit-making company, it is still referred to frequently as ‘The Scott Trust', promulgating the widely-held but mistaken belief in the Guardian’s inherently benign ownership structure. … The problem, of course, is that the Guardian functions under the same sort of corporate structure as any other major media company.

Ahmed details that the Scott Trust board members have deep ties to HSBC. Consider, for example, board member Anthony Salz’s CV, care of Ahmed:

- a senior investment banker and executive vice chairman of Rothschild, and a director at NM Rothschild and Sons. He was a key legal adviser to Guinness during the notorious share-rigging scandal, helped Rupert Murdoch form BSkyB, and was vice chair of the BBC’s Board of Governors before it was replaced by the BBC Trust. He was also lead non-executive director of the board at the Department for Education under arch-neoconservative Michael Gove. Until 2006, Salz led a highly successful 30 year career as a corporate lawyer at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, where he was head and senior managing partner since 1996.

One of Freshfield’s most prominent long-term clients is HSBC. In 2012, Salz’s former firm was appointed to advise HSBC on its record $1.9 billion fine from US authorities for money-laundering, regarding its UK law implications. Although that occurred well after Salz’s time, HSBC’s relationship with Freshfields had been consolidated under Salz’s tenure shortly before he left, establishing an advisory monopoly on much of HSBC’s corporate work in Asia, and displacing the rival firm Norton Rose as HSBC’s advisor of choice.

I strongly recommend you take the time out to read Ahmed’s report in full.

Whistleblower Nicholas Wilson is now trying to crowd-fund a legal action against HSBC that might finally bring its practices to light. It’s a sad indictment of our political rulers, legal authorities and “free press” that our only, slim hope of holding those in power to account is through crowd-funded journalism and crowd-funded court cases.

UPDATE:

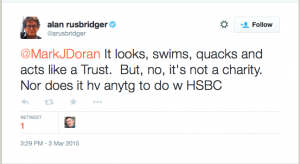

Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger has responded on Twitter to Ahmed’s criticisms.

It is typical evasion from Rusbridger. First, he admits that the Scott Trust Ltd is not a charity, but nonetheless insists it acts “like a trust”. One wonders then why the Guardian didn’t leave it as a trust. Why change it into a limited company, if it‘s only role is to be a trust?

Second, what makes the Scott Trust Ltd different from other corporate media organisations – as we keep being told by its staff, including columnists like George Monbiot and Owen Jones – if, as Rusbridger claims, its board members’ strong ties to corporations like HSBC are irrelevant to understanding its influence on the Guardian? Why are the Trust board members, deeply embedded in the corporate culture, any different from other corporate media chief executives? It seems Rusbridger is in deep denial.

References

- ↑ "UK Media Regulator Again Threatens RT for “Bias”: This Time, Airing 'Anti-Western Views'”

- ↑ "Pinkoes and Traitors by Jean Seaton review – my father, the BBC and a very British coup"

- ↑ "Going Underground: Media oligarchs, food secrecy, & AIPAC lobbyists"

- ↑ "Death, drugs, and HSBC - Fraudulent blood money makes the world go round"