Difference between revisions of "Michael Dukakis"

(Added: sourcewatch, children. Extra Jobs: Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 13th Norfolk district, Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 10th Norfolk district.) |

m (Text replacement - "the powerful" to "the influential") |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <div style="border:2px solid #3333ff; background-color:#ccccff; padding:0.4em 0.5em; margin:auto; width:40%; text-align:center;"> | ||

| + | [[File:too shallow.png|left|72px]] | ||

| + | '''This page is lacking a [[deep political]] perspective'''.<br/>Please rework this to show the hand of the [[deep state]].</div> | ||

{{person | {{person | ||

|image=Mike_Dukakis.jpg | |image=Mike_Dukakis.jpg | ||

| Line 50: | Line 53: | ||

'''Michael Stanley Dukakis''' (nicknamed "Duke") is the former Massachusetts governor who became Democratic nominee in the 1988 US presidential election, which he and his running mate [[Lloyd Bentsen]] lost to the Republican candidate, the then [[US Vice-President]] [[George H W Bush]], and [[Dan Quayle]]. | '''Michael Stanley Dukakis''' (nicknamed "Duke") is the former Massachusetts governor who became Democratic nominee in the 1988 US presidential election, which he and his running mate [[Lloyd Bentsen]] lost to the Republican candidate, the then [[US Vice-President]] [[George H W Bush]], and [[Dan Quayle]]. | ||

| − | Twenty years later, Michael Dukakis reflected on his defeat during an interview with CBS news anchor [[Katie Couric]], in which he said he "owe[d] the American people an apology" because "if I had beaten the [[George H W Bush|old man]], we never would have heard of [[George W Bush|the kid]], and we wouldn't be in this mess."<ref> | + | Twenty years later, Michael Dukakis reflected on his defeat during an interview with CBS news anchor [[Katie Couric]], in which he said he "owe[d] the American people an apology" because "if I had beaten the [[George H W Bush|old man]], we never would have heard of [[George W Bush|the kid]], and we wouldn't be in this mess."<ref>http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=4386669n </ref> |

In December 2014, Michael Dukakis gave his account of the 1988 presidential election campaign in a documentary entitled [http://www.msnbc.com/hardball/watch/above-the-fray-a-documentary-374326851877 "Above The Fray"]. In the documentary, Mike Dukakis explained that it was President [[Ronald Reagan]]'s television address of 4 March 1987 about the appalling [[Iran-Contra affair]] that had prompted him to stand for the presidency. Initially Dukakis and the other Democratic candidates were relatively unknown nationwide, but his campaign sprang to life when his press secretary [[John Sasso]] was found to have leaked damaging details about another candidate [[Joe Biden]] who had plagiarised a speech by [[Neil Kinnock]], the British opposition leader. When Dukakis sacked Sasso he saw his poll ratings starting to rise. [[President Reagan]] then hinted on television that Dukakis had suffered from mental illness, saying it would be wrong "to pick on an invalid", and the campaign stalled. However, by the time of the Democratic National Convention in July 1988, when Dukakis had been selected as the Democratic nominee, he had taken a strong lead over [[George H W Bush]], the Republican candidate. Dukakis maintained the lead until the second televised presidential debate which took place on 13 October 1988. He was asked by the moderator of the debate whether he would support the death penalty against somebody who had raped and murdered his wife Kitty. Dukakis' negative response caused his poll rating to fall from 49% to 42% overnight, and was thought to have cost him the election three weeks later.<ref>[http://www.msnbc.com/hardball/watch/above-the-fray-a-documentary-374326851877 "Above The Fray"]</ref> | In December 2014, Michael Dukakis gave his account of the 1988 presidential election campaign in a documentary entitled [http://www.msnbc.com/hardball/watch/above-the-fray-a-documentary-374326851877 "Above The Fray"]. In the documentary, Mike Dukakis explained that it was President [[Ronald Reagan]]'s television address of 4 March 1987 about the appalling [[Iran-Contra affair]] that had prompted him to stand for the presidency. Initially Dukakis and the other Democratic candidates were relatively unknown nationwide, but his campaign sprang to life when his press secretary [[John Sasso]] was found to have leaked damaging details about another candidate [[Joe Biden]] who had plagiarised a speech by [[Neil Kinnock]], the British opposition leader. When Dukakis sacked Sasso he saw his poll ratings starting to rise. [[President Reagan]] then hinted on television that Dukakis had suffered from mental illness, saying it would be wrong "to pick on an invalid", and the campaign stalled. However, by the time of the Democratic National Convention in July 1988, when Dukakis had been selected as the Democratic nominee, he had taken a strong lead over [[George H W Bush]], the Republican candidate. Dukakis maintained the lead until the second televised presidential debate which took place on 13 October 1988. He was asked by the moderator of the debate whether he would support the death penalty against somebody who had raped and murdered his wife Kitty. Dukakis' negative response caused his poll rating to fall from 49% to 42% overnight, and was thought to have cost him the election three weeks later.<ref>[http://www.msnbc.com/hardball/watch/above-the-fray-a-documentary-374326851877 "Above The Fray"]</ref> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 61: | ||

===First governorship (1975–1979)=== | ===First governorship (1975–1979)=== | ||

| − | After serving four terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives between 1962 and 1970 (and winning the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor in 1970<ref>[http://www.hri.org/hri/dukakis.html "Biographical information"]</ref>), Dukakis was elected governor in 1974, defeating the incumbent Republican Francis Sargent during a period of fiscal crisis. Dukakis won in part by promising to be a "reformer" and pledging a "lead pipe guarantee" of no new taxes to balance the state budget. He would later reverse his position after taking office. He also pledged to dismantle the | + | After serving four terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives between 1962 and 1970 (and winning the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor in 1970<ref>[http://www.hri.org/hri/dukakis.html "Biographical information"]</ref>), Dukakis was elected governor in 1974, defeating the incumbent Republican Francis Sargent during a period of fiscal crisis. Dukakis won in part by promising to be a "reformer" and pledging a "lead pipe guarantee" of no new taxes to balance the state budget. He would later reverse his position after taking office. He also pledged to dismantle the influential [[Metropolitan District Commission]] (MDC), a bureaucratic enclave that served as home to hundreds of political patronage employees. The MDC managed state parks, reservoirs, and waterways, as well as the highways and roads abutting those waterways. In addition to its own police force, the MDC had its own maritime patrol force, and an enormous budget from the state, for which it provided minimal accounting. Dukakis' efforts to dismantle the MDC failed in the legislature, where the MDC had many powerful supporters. As a result, the MDC would withhold its critical backing of Dukakis in the 1978 gubernatorial primary. |

| − | Governor Dukakis hosted [[Gerald Ford|President Ford]] and Britain's [[Queen Elizabeth II]] during their visits to Boston in 1976 to commemorate the bicentennial of the United States. He gained some notice as the only politician in the state government who went to work during the Blizzard of 1978, when he went to local TV studios in a sweater to announce emergency bulletins.<ref> | + | Governor Dukakis hosted [[Gerald Ford|President Ford]] and Britain's [[Queen Elizabeth II]] during their visits to Boston in 1976 to commemorate the bicentennial of the United States. He gained some notice as the only politician in the state government who went to work during the Blizzard of 1978, when he went to local TV studios in a sweater to announce emergency bulletins.<ref>http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/02/03/have_we_learned_anything/?page=full </ref> Dukakis is also remembered for his 1977 exoneration of Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists whose trial sparked protests around the world. |

| − | During his first term in office, Dukakis commuted the sentences of 21 first-degree murderers and 23 second-degree murderers. Due to controversy engendered by some of these individuals having re-offended, Dukakis curtailed the practice later, issuing no commutations in his last three years as governor.<ref> | + | During his first term in office, Dukakis commuted the sentences of 21 first-degree murderers and 23 second-degree murderers. Due to controversy engendered by some of these individuals having re-offended, Dukakis curtailed the practice later, issuing no commutations in his last three years as governor.<ref>http://news.bostonherald.com/columnists/view.bg?articleid=160964</ref> |

| − | However, his first term performance proved to be insufficient to offset a backlash against the state's high sales and property tax rates, which turned out to be the predominant issue in the 1978 gubernatorial campaign. Dukakis, despite being the incumbent Democratic governor, was refused renomination by his own party. The state's Democratic Party chose to support Director of the Massachusetts Port Authority Edward J. King in the primary, partly because King rode the wave against high property taxes, but more significantly because state Democratic Party leaders lost confidence in Dukakis' ability to govern effectively. King also enjoyed the support of the power brokers at the MDC, who were unhappy with Dukakis' attempts to dismantle their powerful [[bureaucracy]]. King also had support from state police and public employee unions. Dukakis suffered a scathing defeat in the primary, a disappointment that his wife Kitty called "a public death".<ref> | + | However, his first term performance proved to be insufficient to offset a backlash against the state's high sales and property tax rates, which turned out to be the predominant issue in the 1978 gubernatorial campaign. Dukakis, despite being the incumbent Democratic governor, was refused renomination by his own party. The state's Democratic Party chose to support Director of the Massachusetts Port Authority Edward J. King in the primary, partly because King rode the wave against high property taxes, but more significantly because state Democratic Party leaders lost confidence in Dukakis' ability to govern effectively. King also enjoyed the support of the power brokers at the MDC, who were unhappy with Dukakis' attempts to dismantle their powerful [[bureaucracy]]. King also had support from state police and public employee unions. Dukakis suffered a scathing defeat in the primary, a disappointment that his wife Kitty called "a public death".<ref>http://articles.latimes.com/print/1988-01-17/news/mn-36772_1_michael-dukaki</ref> |

===Second governorship (1983–1991)=== | ===Second governorship (1983–1991)=== | ||

Four years later, having made peace with the state Democratic Party, MDC, the state police and public employee unions, Michael Dukakis defeated King in a 're-match' in the 1982 Democratic primary. He went on to defeat his Republican opponent, John Winthrop Sears, in the November election. Future United States Senator, 2004 Democratic Presidential nominee, and US Secretary of State [[John Kerry]] was elected lieutenant governor on the same ballot with Dukakis, and served in the Dukakis administration from 1983 to 1985. | Four years later, having made peace with the state Democratic Party, MDC, the state police and public employee unions, Michael Dukakis defeated King in a 're-match' in the 1982 Democratic primary. He went on to defeat his Republican opponent, John Winthrop Sears, in the November election. Future United States Senator, 2004 Democratic Presidential nominee, and US Secretary of State [[John Kerry]] was elected lieutenant governor on the same ballot with Dukakis, and served in the Dukakis administration from 1983 to 1985. | ||

| − | Dukakis served as governor during which time he presided over a high-tech boom and a period of prosperity in Massachusetts while simultaneously earning a reputation as a 'technocrat'. The National Governors Association voted Dukakis the most effective governor in 1986. Residents of the city of Boston and its surrounding areas remember him for the improvements he made to Boston's mass transit system, especially major renovations to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority's trains and buses. He was known for riding the subway to work every day as governor.<ref> | + | Dukakis served as governor during which time he presided over a high-tech boom and a period of prosperity in Massachusetts while simultaneously earning a reputation as a 'technocrat'. The National Governors Association voted Dukakis the most effective governor in 1986. Residents of the city of Boston and its surrounding areas remember him for the improvements he made to Boston's mass transit system, especially major renovations to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority's trains and buses. He was known for riding the subway to work every day as governor.<ref>http://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/23/us/boston-in-transit-war-against-uneasy-riding.html</ref><ref>http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/01/31/south-station-may-track-for-new-name-that-mike-dukakis/GBlBTJUC0HJDf94wKYN9yM/story.html</ref> |

| − | In 1988, Dukakis and Rosabeth Moss Kanter, his economic adviser in the 1988 presidential elections, wrote a book entitled ''Creating the Future: the Massachusetts Comeback and Its Promise for America'', an examination of the Massachusetts Miracle.<ref> | + | In 1988, Dukakis and Rosabeth Moss Kanter, his economic adviser in the 1988 presidential elections, wrote a book entitled ''Creating the Future: the Massachusetts Comeback and Its Promise for America'', an examination of the Massachusetts Miracle.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/1988/05/01/books/what-you-see-is-what-you-get.html?pagewanted=all "What you see is what you get"].</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=59Qi-X9PEgoC&pg=PA231 Sheldrake, John (2003). Management theory. London: Thomson Learning. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-86152-963-3.]</ref> |

==1988 presidential campaign== | ==1988 presidential campaign== | ||

| Line 110: | Line 113: | ||

Dukakis had trouble with the personality that he projected to the voting public. His reserved and stoic nature was easily interpreted to be a lack of passion; Dukakis was often referred to as "Zorba the Clerk". Nevertheless, Dukakis is considered to have done well in the first presidential debate with [[George H W Bush|George Bush]], but in the second debate, Dukakis had been suffering from the flu and spent much of the day in bed. His performance was poor and played to his reputation as being cold. During the campaign, Dukakis' mental health became an issue when he refused to release his full medical history and there were, according to ''The New York Times'', "persistent suggestions" that he had undergone psychiatric treatment in the past.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/1988/08/04/us/dukakis-releases-medical-details-to-stop-rumors-on-mental-health.html?pagewanted=all "Dukakis Releases Medical Details To Stop Rumors on Mental Health"], ''The New York Times'', August 4, 1988.</ref> In the 2008 film ''Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story'', journalist Robert Novak revealed that Republican strategist Lee Atwater had personally tried to get him to spread these mental-health rumours.<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/atwater/etc/script.html ''Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story''] transcript, Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), director: Stefan Forbes, 2008.</ref> | Dukakis had trouble with the personality that he projected to the voting public. His reserved and stoic nature was easily interpreted to be a lack of passion; Dukakis was often referred to as "Zorba the Clerk". Nevertheless, Dukakis is considered to have done well in the first presidential debate with [[George H W Bush|George Bush]], but in the second debate, Dukakis had been suffering from the flu and spent much of the day in bed. His performance was poor and played to his reputation as being cold. During the campaign, Dukakis' mental health became an issue when he refused to release his full medical history and there were, according to ''The New York Times'', "persistent suggestions" that he had undergone psychiatric treatment in the past.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/1988/08/04/us/dukakis-releases-medical-details-to-stop-rumors-on-mental-health.html?pagewanted=all "Dukakis Releases Medical Details To Stop Rumors on Mental Health"], ''The New York Times'', August 4, 1988.</ref> In the 2008 film ''Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story'', journalist Robert Novak revealed that Republican strategist Lee Atwater had personally tried to get him to spread these mental-health rumours.<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/atwater/etc/script.html ''Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story''] transcript, Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), director: Stefan Forbes, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | Dukakis' general election campaign was subject to several criticisms and gaffes on issues such as capital punishment, the pledge of allegiance in schools, and most famously, the Michael Dukakis tank photograph. Like the allegations of psychiatric problems, these were vulnerabilities which Atwater identified and exploited. In 1991, shortly before his death from a brain tumour, Atwater apologised to Dukakis for the "naked cruelty" of the 1988 campaign.<ref> | + | Dukakis' general election campaign was subject to several criticisms and gaffes on issues such as capital punishment, the pledge of allegiance in schools, and most famously, the Michael Dukakis tank photograph. Like the allegations of psychiatric problems, these were vulnerabilities which Atwater identified and exploited. In 1991, shortly before his death from a brain tumour, Atwater apologised to Dukakis for the "naked cruelty" of the 1988 campaign.<ref>http://www.nytimes.com/1991/01/13/us/gravely-ill-atwater-offers-apology.html</ref><ref>http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2008/05/05/080505taco_talk_wickenden</ref> |

===Crime issues=== | ===Crime issues=== | ||

| Line 137: | Line 140: | ||

After the end of his term, he served on the board of directors for Amtrak, and became a professor of political science at Northeastern University, a visiting professor of political science at Loyola Marymount University, and visiting professor in the Department of Public Policy at the School of Public Affairs at University of California, Los Angeles. Along with a number of other notable Greek Americans, he is a founding member of ''The Next Generation Initiative'': a leadership program aimed at getting students involved in public affairs. In November 2008, Northeastern named its new Center for Urban and Regional Policy after Michael Dukakis and his wife Kitty. | After the end of his term, he served on the board of directors for Amtrak, and became a professor of political science at Northeastern University, a visiting professor of political science at Loyola Marymount University, and visiting professor in the Department of Public Policy at the School of Public Affairs at University of California, Los Angeles. Along with a number of other notable Greek Americans, he is a founding member of ''The Next Generation Initiative'': a leadership program aimed at getting students involved in public affairs. In November 2008, Northeastern named its new Center for Urban and Regional Policy after Michael Dukakis and his wife Kitty. | ||

| − | Dukakis has developed a strong passion for grassroots campaigning and the appointment of precinct captains to coordinate local campaigning activities, two strategies he feels are essential for the Democratic Party to compete effectively in both local and national elections. In 2006, he and his wife worked to help Democratic candidate Deval Patrick in his successful effort to become Governor of Massachusetts. In August 2009, the 75-year-old Dukakis was mentioned as one of two leading candidates as a possible interim successor to Ted Kennedy in the US Senate, after Kennedy's death.<ref> | + | Dukakis has developed a strong passion for grassroots campaigning and the appointment of precinct captains to coordinate local campaigning activities, two strategies he feels are essential for the Democratic Party to compete effectively in both local and national elections. In 2006, he and his wife worked to help Democratic candidate Deval Patrick in his successful effort to become Governor of Massachusetts. In August 2009, the 75-year-old Dukakis was mentioned as one of two leading candidates as a possible interim successor to Ted Kennedy in the US Senate, after Kennedy's death.<ref>http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2009/08/21/who_should_fill_kennedys_seat/</ref><ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8269945.stm </ref> Instead, Governor Patrick named Paul G. Kirk, the other leading candidate and favourite of the Kennedy family who promised not to run in the special election, to fill the seat.<ref>http://www.cnn.com/2009/POLITICS/09/24/kennedy.replacement/index.html</ref> |

| − | Dukakis stated on 31 January 2014 that he was not in favour of an effort to rename South Station as the "Gov. Michael S. Dukakis Transportation Center". He went on to state that he would not object to the naming the as-yet unbuilt North-South Rail Link after him.<ref> | + | Dukakis stated on 31 January 2014 that he was not in favour of an effort to rename South Station as the "Gov. Michael S. Dukakis Transportation Center". He went on to state that he would not object to the naming the as-yet unbuilt North-South Rail Link after him.<ref>http://bostonherald.com/news_opinion/local_coverage/2014/01/michael_dukakis_decries_terminal_honor</ref> |

==Family== | ==Family== | ||

Latest revision as of 13:12, 18 October 2024

Please rework this to show the hand of the deep state.

(politician) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Democratic nominee for the 1988 US presidential election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Michael Stanley Dukakis 1933-11-03 Brookline, Massachusetts, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Swarthmore College, Harvard Law School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Greek Orthodox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | • John • Andrea • Kara | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Kitty Dickson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of | National Democratic Institute/Board and Staff | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Democratic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Michael Stanley Dukakis (nicknamed "Duke") is the former Massachusetts governor who became Democratic nominee in the 1988 US presidential election, which he and his running mate Lloyd Bentsen lost to the Republican candidate, the then US Vice-President George H W Bush, and Dan Quayle.

Twenty years later, Michael Dukakis reflected on his defeat during an interview with CBS news anchor Katie Couric, in which he said he "owe[d] the American people an apology" because "if I had beaten the old man, we never would have heard of the kid, and we wouldn't be in this mess."[1]

In December 2014, Michael Dukakis gave his account of the 1988 presidential election campaign in a documentary entitled "Above The Fray". In the documentary, Mike Dukakis explained that it was President Ronald Reagan's television address of 4 March 1987 about the appalling Iran-Contra affair that had prompted him to stand for the presidency. Initially Dukakis and the other Democratic candidates were relatively unknown nationwide, but his campaign sprang to life when his press secretary John Sasso was found to have leaked damaging details about another candidate Joe Biden who had plagiarised a speech by Neil Kinnock, the British opposition leader. When Dukakis sacked Sasso he saw his poll ratings starting to rise. President Reagan then hinted on television that Dukakis had suffered from mental illness, saying it would be wrong "to pick on an invalid", and the campaign stalled. However, by the time of the Democratic National Convention in July 1988, when Dukakis had been selected as the Democratic nominee, he had taken a strong lead over George H W Bush, the Republican candidate. Dukakis maintained the lead until the second televised presidential debate which took place on 13 October 1988. He was asked by the moderator of the debate whether he would support the death penalty against somebody who had raped and murdered his wife Kitty. Dukakis' negative response caused his poll rating to fall from 49% to 42% overnight, and was thought to have cost him the election three weeks later.[2]

Contents

Massachusetts governor

Michael Dukakis served as the 65th and 67th Governor of Massachusetts, from 1975 to 1979 and 1983 to 1991 respectively. He is the longest-serving Governor in Massachusetts history and only the second ever Greek American Governor after Spiro Agnew.

First governorship (1975–1979)

After serving four terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives between 1962 and 1970 (and winning the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor in 1970[3]), Dukakis was elected governor in 1974, defeating the incumbent Republican Francis Sargent during a period of fiscal crisis. Dukakis won in part by promising to be a "reformer" and pledging a "lead pipe guarantee" of no new taxes to balance the state budget. He would later reverse his position after taking office. He also pledged to dismantle the influential Metropolitan District Commission (MDC), a bureaucratic enclave that served as home to hundreds of political patronage employees. The MDC managed state parks, reservoirs, and waterways, as well as the highways and roads abutting those waterways. In addition to its own police force, the MDC had its own maritime patrol force, and an enormous budget from the state, for which it provided minimal accounting. Dukakis' efforts to dismantle the MDC failed in the legislature, where the MDC had many powerful supporters. As a result, the MDC would withhold its critical backing of Dukakis in the 1978 gubernatorial primary.

Governor Dukakis hosted President Ford and Britain's Queen Elizabeth II during their visits to Boston in 1976 to commemorate the bicentennial of the United States. He gained some notice as the only politician in the state government who went to work during the Blizzard of 1978, when he went to local TV studios in a sweater to announce emergency bulletins.[4] Dukakis is also remembered for his 1977 exoneration of Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists whose trial sparked protests around the world.

During his first term in office, Dukakis commuted the sentences of 21 first-degree murderers and 23 second-degree murderers. Due to controversy engendered by some of these individuals having re-offended, Dukakis curtailed the practice later, issuing no commutations in his last three years as governor.[5]

However, his first term performance proved to be insufficient to offset a backlash against the state's high sales and property tax rates, which turned out to be the predominant issue in the 1978 gubernatorial campaign. Dukakis, despite being the incumbent Democratic governor, was refused renomination by his own party. The state's Democratic Party chose to support Director of the Massachusetts Port Authority Edward J. King in the primary, partly because King rode the wave against high property taxes, but more significantly because state Democratic Party leaders lost confidence in Dukakis' ability to govern effectively. King also enjoyed the support of the power brokers at the MDC, who were unhappy with Dukakis' attempts to dismantle their powerful bureaucracy. King also had support from state police and public employee unions. Dukakis suffered a scathing defeat in the primary, a disappointment that his wife Kitty called "a public death".[6]

Second governorship (1983–1991)

Four years later, having made peace with the state Democratic Party, MDC, the state police and public employee unions, Michael Dukakis defeated King in a 're-match' in the 1982 Democratic primary. He went on to defeat his Republican opponent, John Winthrop Sears, in the November election. Future United States Senator, 2004 Democratic Presidential nominee, and US Secretary of State John Kerry was elected lieutenant governor on the same ballot with Dukakis, and served in the Dukakis administration from 1983 to 1985.

Dukakis served as governor during which time he presided over a high-tech boom and a period of prosperity in Massachusetts while simultaneously earning a reputation as a 'technocrat'. The National Governors Association voted Dukakis the most effective governor in 1986. Residents of the city of Boston and its surrounding areas remember him for the improvements he made to Boston's mass transit system, especially major renovations to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority's trains and buses. He was known for riding the subway to work every day as governor.[7][8]

In 1988, Dukakis and Rosabeth Moss Kanter, his economic adviser in the 1988 presidential elections, wrote a book entitled Creating the Future: the Massachusetts Comeback and Its Promise for America, an examination of the Massachusetts Miracle.[9][10]

1988 presidential campaign

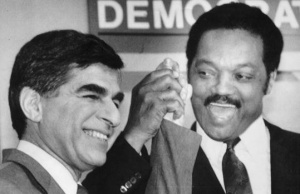

Using the phenomenon termed the "Massachusetts Miracle" to promote his campaign, Michael Dukakis sought the Democratic Party nomination for President of the United States in the 1988 United States presidential election, prevailing over a primary field that included Jesse Jackson, Dick Gephardt, Paul Simon, Gary Hart, Joe Biden and Al Gore, among others. Touching on his immigrant roots, Dukakis used Neil Diamond's ode to immigrants, "America", as the theme song for his campaign. Famed composer John Williams wrote "Fanfare for Michael Dukakis" in 1988 at the request of Dukakis's father-in-law, Harry Ellis Dickson. The piece was premiered under the baton of Dickson (then the Associate Conductor of the Boston Pops) at that year's Democratic National Convention (DNC). By early June 1988 Dukakis had secured enough votes in the final primary elections to win the nomination at the DNC, where the platform was scheduled to be considered and agreed.

Drafting the platform

At a meeting in Michigan on 12 June 1988, backers of the Dukakis presidential campaign yielded to the Rev. Jesse Jackson's demand that South Africa be branded a "terrorist state" in the Democratic Party's platform. Representatives of both men said they had bridged their differences on the South Africa issue, but Dukakis' aides refused to agree to the civil rights leader's demands that the platform call for higher taxes, support for a Palestinian homeland and a military spending freeze.

In their draft, the platform writers included broad proposals on education, civil rights, housing, health care and the economy, as well as on labour, energy and the environment. Neither Dukakis nor Jackson was at this first series of platform-drafting meetings at the luxury resort of Mackinac Island. The Massachusetts Governor, who favours strong sanctions and a divestment of United States industries in South Africa to protest its racial segregation policies, had resisted calling South Africa a "terrorist state".

On the economy, the draft was silent about raising taxes but said that after eight years of devastating Republican policies, Democrats want progressive values, with a strong commitment to fiscal responsibility. Jackson wanted higher taxes on the wealthy and on corporations to pay for social programs and cut the deficit. Dukakis wanted more stringent collection of existing taxes.

Labelling South Africa a "terrorist state" because of apartheid and its alleged encroachment on neighbouring states would put it in the same category as Libya and Iran, countries considered outlaw states by the United States, and trigger automatic sanctions. Dukakis spokesmen refused to say they had surrendered on branding South Africa a "terrorist state". His foreign policy adviser, Madeleine Albright, told reporters the dispute involved a semantical difference.

But although the platform language on South Africa was incomplete, supporters of both Dukakis and Jackson said it would describe South Africa as a "terrorist state". Eleanor Holmes Norton, Jackson's chief representative at the meeting, said:

- "We are very pleased the Governor has come to the Jackson position on this issue." Ms Norton also said enormous progress had been made on differences over domestic issues between Gov. Dukakis and Rev. Jackson, who had threatened platform fights at the convention.[11]

The double standards on "terrorism"

The agreed Democratic platform position on apartheid South Africa being regarded as a "terrorist state" was highlighted by former British diplomat Patrick Haseldine in this letter published in The Guardian on 7 December 1988:

- It is all very well for Mrs Thatcher to inveigh against the Belgians and the Irish with such self-righteous invective. Naturally, she would not care to admit it but in the not too distant past her allegations of being soft on "terrorism" and allowing political considerations to override the due legal process could have been levelled at Mrs Thatcher herself.

- Remember the Coventry Four? These were the four (white) South Africans brought before Coventry magistrates in March 1984 and remanded in custody on arms embargo charges. Rumour has it that Mrs Thatcher was rather annoyed with the over-zealous officials who caused the four military personnel to be arrested in Britain. Rightly, she refused to accede to the South African embassy's demand for the case to be dropped but she was keen for the embassy to know precisely how the legal hurdles governing their release and the return of their passports could be swiftly overcome. Thus the First Secretary at the embassy stood bail for the Coventry Four, having declared in court that he was waiving his diplomatic immunity. (The embassy did not, however, formally confirm the waiver.) Then a petition to an English Judge in Chambers secured the repatriation of the four accused.

- Clearly, Mrs Thatcher wanted the four high-profile detainees safely out of UK jurisdiction, back in South Africa and off the agenda well before her June 1984 talks at Chequers with the two visiting Bothas (P W Botha and Pik Botha). Strange that Pik Botha, the foreign minister, was able to find an excuse for not allowing the Coventry Four to stand trial in the Autumn of 1984.

- Stranger still that Mrs Thatcher failed to denounce Mr Botha's refusal to surrender the four 'terrorists' (cf declaration by U.S. Governor Michael Dukakis that South Africa is a 'terrorist state').

Democratic National Convention

Michael Dukakis won the Democratic nomination, with 2,877 out of 4,105 delegates, and chose US Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas to be his vice-presidential running mate. In his acceptance speech on 21 July 1988, Dukakis talked about "A New Era of Greatness for America":

- Mr Chairman, A few months ago when Olympia Dukakis, in front of about a billion and a half television viewers all over the world, raised that Oscar over her head and said, "OK, Michael, let's go," she wasn't kidding.

- Kitty and I are grateful to her for that wonderful introduction and grateful to all of you for making this possible. This is a wonderful evening for us and we thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

- My fellow Democrats, My fellow Americans,

- Sixteen months ago, when I announced my candidacy for the Presidency of the United States, I said this campaign would be a marathon. Tonight, with the wind at our backs; with friends by our side; with courage in our hearts; the race to the finish line begins. And we're going to win this race.

- We're going to win because we are the party that believes in the American dream.[12]

Zorba the Clerk

Dukakis had trouble with the personality that he projected to the voting public. His reserved and stoic nature was easily interpreted to be a lack of passion; Dukakis was often referred to as "Zorba the Clerk". Nevertheless, Dukakis is considered to have done well in the first presidential debate with George Bush, but in the second debate, Dukakis had been suffering from the flu and spent much of the day in bed. His performance was poor and played to his reputation as being cold. During the campaign, Dukakis' mental health became an issue when he refused to release his full medical history and there were, according to The New York Times, "persistent suggestions" that he had undergone psychiatric treatment in the past.[13] In the 2008 film Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story, journalist Robert Novak revealed that Republican strategist Lee Atwater had personally tried to get him to spread these mental-health rumours.[14]

Dukakis' general election campaign was subject to several criticisms and gaffes on issues such as capital punishment, the pledge of allegiance in schools, and most famously, the Michael Dukakis tank photograph. Like the allegations of psychiatric problems, these were vulnerabilities which Atwater identified and exploited. In 1991, shortly before his death from a brain tumour, Atwater apologised to Dukakis for the "naked cruelty" of the 1988 campaign.[15][16]

Crime issues

During the campaign, Vice-President George H W Bush, the Republican nominee, criticised Dukakis for his traditionally liberal positions on many issues, calling him "a card-carrying member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)". Dukakis' support for a prison furlough program was a major election subject. During his first term as Governor, he had vetoed a bill that would have stopped furloughs for first-degree murderers.[17] During his second term, that program resulted in the release of convicted murderer Willie Horton,[18] who committed a rape and assault in Maryland after being furloughed. George H W Bush mentioned Horton by name in a speech in June 1988, and a conservative political action committee (PAC) affiliated with the Bush campaign, the National Security Political Action Committee, aired an ad entitled "Weekend Passes", which used a mug shot image of Horton. The Bush campaign refused to repudiate the ad. That advertising campaign was followed by a separate Bush campaign ad, "Revolving Door", criticising Dukakis over the furlough program without mentioning Horton. The legislature cancelled the program during Dukakis' last term.

The issue of capital punishment came up in the 13 October 1988 debate between the two presidential nominees. Because she knew the Willie Horton issue would be brought up, Dukakis's campaign manager, Susan Estrich, had prepared with Michael Dukakis an answer highlighting the candidate's empathy for victims of crime, noting the beating of his father in a robbery and the death of his brother in a hit-and-run car accident. However, when Bernard Shaw, the moderator of the debate, asked Dukakis, "Governor, if Kitty Dukakis [his wife] were raped and murdered, would you favour an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?" Dukakis replied, "No, I don't, and I think you know that I've opposed the death penalty during all of my life", and explained his stance. After the debate,[19] many observers felt Dukakis's answer lacked the passion one would expect of a person discussing a loved one's rape and death. Many – including Dukakis himself – believe this, in part, cost him the election, as his poll numbers dropped from 49% to 42% nationally that night. Other commentators thought the question itself was unfair, in that it injected an irrelevant emotional element into the discussion of a policy issue and forced the candidate to make a difficult choice, while others believed that Dukakis dwelled too much on post-mortem reflections about this incident while the election was still in play in a way that was too self-effacing to the point of appearing self-pitying and defeatist, which only served to demoralise his campaign and reinforce the image of him as a weak leader.

Tank photograph

Dukakis was criticised during the campaign for a perceived softness on defence issues, particularly the controversial "Star Wars" program, which he promised to weaken. In response to this, Dukakis orchestrated what would become the key image of his campaign, although it turned out quite differently from what he intended. On 13 September 1988, Dukakis visited the General Dynamics Land Systems plant in Sterling Heights, Michigan to take part in a photo op in an M1 Abrams tank.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, had been photographed in a similar situation in 1986, riding in a Challenger tank while wearing a scarf.[20] Compared with Dukakis' results, Thatcher's picture was very successful and helped her re-election prospects.[21] Footage of Dukakis was used in television ads by the Bush campaign, as evidence that Dukakis would not make a good commander-in-chief, and "Dukakis in the tank" remains shorthand for backfired public relations outings.

Outcome

The Dukakis/Bentsen ticket lost the election by a decisive margin in the Electoral College to George H W Bush and Dan Quayle, carrying only 10 states and the Washington, DC. Dukakis himself blames his defeat on the time he spent doing gubernatorial work in Massachusetts during the few weeks following the Democratic Convention. Many believed he should have been campaigning across the country. During this time, his 17-point lead in opinion polls completely disappeared, as his lack of visibility allowed Bush to define the issues of the campaign. Dukakis has since stated that the main reason he lost was his decision "not to respond to the Bush attack campaign, and in retrospect it was a pretty dumb decision."[22]

Despite Dukakis's loss, his performance was a marked improvement over the previous two Democratic efforts. Dukakis made some strong showings in states that had voted for Republicans Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford. He managed to pull off a close win in New York which at the time was the second largest state in terms of electoral votes, he also scored victories in states like Rhode Island, Hawaii, and Dukakis' home state of Massachusetts; Walter Mondale had lost all four, and since then, all three states have remained in the Democratic column for each subsequent presidential election. He swept Iowa, winning by 10 points, an impressive feat in a state that had voted Republican in the last five presidential elections. He won 43% of the vote in Kansas, a surprising showing in the home state of 1936 Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon, Republican President Dwight Eisenhower, and future Republican nominee Bob Dole. In another surprising showing, he received 47% of the vote in South Dakota; in Montana, Dukakis won 46% of the vote in a state that had voted over 60% Republican four years earlier. Dukakis's relative strength in farm states was no doubt due to the serious economic difficulties these states were facing in the 1980s, and it was the strongest showing in the Midwest for a Democrat since 1976.

Although Dukakis cut into the Republican hold in the Midwest, he failed to dent the emerging GOP stronghold in the South that had been forming since the end of World War II with a temporary reprieve with Jimmy Carter (along with future President and Southern Democrat Bill Clinton, albeit to a much lesser extent). He lost most of the South by a wide margin, with Bush's totals reaching around 60% in most states. He was able to hold Bush to 55% in Texas, though this was most likely due to Texan Lloyd Bentsen's presence on the ticket. He also carried most of the southern-central parishes of Louisiana, despite losing the state. He held onto the border state of West Virginia, and he captured 48% of the vote in Missouri. He also carried 41% in Oklahoma, a bigger share than any Democrat since Jimmy Carter.

Dukakis won 41,809,476 votes in the popular vote. He also received 40% or more in the following states: Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont. Overall, the 1988 election showed a marked improvement in the popular vote for the Democrats. While he lost the popular vote, Dukakis's margin of loss (7.8%) was narrower than Jimmy Carter's in 1980 (9.7%) or Walter Mondale's in 1984 (18.2%).

Post–presidential election

In early January 1989, Dukakis announced that he would not run for a fourth term. His final two years as Governor were marked by increased criticism of his policies and significant tax increases to cover the economic effects of the US economy's "soft landing" at the end of the 1980s and the recession of 1990.

After the end of his term, he served on the board of directors for Amtrak, and became a professor of political science at Northeastern University, a visiting professor of political science at Loyola Marymount University, and visiting professor in the Department of Public Policy at the School of Public Affairs at University of California, Los Angeles. Along with a number of other notable Greek Americans, he is a founding member of The Next Generation Initiative: a leadership program aimed at getting students involved in public affairs. In November 2008, Northeastern named its new Center for Urban and Regional Policy after Michael Dukakis and his wife Kitty.

Dukakis has developed a strong passion for grassroots campaigning and the appointment of precinct captains to coordinate local campaigning activities, two strategies he feels are essential for the Democratic Party to compete effectively in both local and national elections. In 2006, he and his wife worked to help Democratic candidate Deval Patrick in his successful effort to become Governor of Massachusetts. In August 2009, the 75-year-old Dukakis was mentioned as one of two leading candidates as a possible interim successor to Ted Kennedy in the US Senate, after Kennedy's death.[23][24] Instead, Governor Patrick named Paul G. Kirk, the other leading candidate and favourite of the Kennedy family who promised not to run in the special election, to fill the seat.[25]

Dukakis stated on 31 January 2014 that he was not in favour of an effort to rename South Station as the "Gov. Michael S. Dukakis Transportation Center". He went on to state that he would not object to the naming the as-yet unbuilt North-South Rail Link after him.[26]

Family

Michael Dukakis is married to Kitty Dukakis. They have three children: John, Andrea, and Kara. During the second presidential debate on October 13, 1988, in Los Angeles, Dukakis revealed that he and his wife had had another child, who died about 20 minutes after birth. Dukakis is the cousin of actress Olympia Dukakis.[27]

References

- ↑ http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=4386669n

- ↑ "Above The Fray"

- ↑ "Biographical information"

- ↑ http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/02/03/have_we_learned_anything/?page=full

- ↑ http://news.bostonherald.com/columnists/view.bg?articleid=160964

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/print/1988-01-17/news/mn-36772_1_michael-dukaki

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/23/us/boston-in-transit-war-against-uneasy-riding.html

- ↑ http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/01/31/south-station-may-track-for-new-name-that-mike-dukakis/GBlBTJUC0HJDf94wKYN9yM/story.html

- ↑ "What you see is what you get".

- ↑ Sheldrake, John (2003). Management theory. London: Thomson Learning. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-86152-963-3.

- ↑ "Dukakis Backers Agree Platform Will Call South Africa 'Terrorist'"

- ↑ "A New Era of Greatness for America" Address Accepting the Presidential Nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, 21 July 1988

- ↑ "Dukakis Releases Medical Details To Stop Rumors on Mental Health", The New York Times, August 4, 1988.

- ↑ Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story transcript, Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), director: Stefan Forbes, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1991/01/13/us/gravely-ill-atwater-offers-apology.html

- ↑ http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2008/05/05/080505taco_talk_wickenden

- ↑ Oshinsky, David. "What Became of the Democrats", The New York Times (October 20, 1991): "In 1976 the state legislature passed a bill that would have ended the furloughs of first-degree murderers. Governor Dukakis, as the Edsalls point out, vetoed it. A strong advocate of prisoners' rights, he contended that the bill would 'cut the heart out of efforts at inmate rehabilitation.'"

- ↑ Crime, Risk and Insecurity" ed. Tim Hope and Richard Sparks, p. 266

- ↑ The Debates", Newsmax September 2004 (copy at the Internet Archive)

- ↑ "BBC - Radio4 - Today/The Fate of Tanks"

- ↑ "100 Photographs that Changed the World by Life - The Digital Journalist"

- ↑ "Dukakis and the Tank"

- ↑ http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2009/08/21/who_should_fill_kennedys_seat/

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8269945.stm

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/2009/POLITICS/09/24/kennedy.replacement/index.html

- ↑ http://bostonherald.com/news_opinion/local_coverage/2014/01/michael_dukakis_decries_terminal_honor

- ↑ IMDb — Biography for Michael Dukakis. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

External links

- Official Commonwealth of Massachusetts Governors Biography

- Faculty Page at the Northeastern University Department of Political Science

- Faculty Page at UCLA

- The Michael S. Dukakis Presidential Campaign records, 1962–1989 (bulk 1987–1988) are located in the Northeastern University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections Department, Boston, MA.

- The Joseph D. Warren papers, 1972–2003 (bulk 1980–1990) are located in the Northeastern University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections Department, Boston, MA.

- Dukakis discusses presidential debates as reported in the Harvard Law Record

- Dukakis mentioned on MSNBC's Morning Joe: The Scoop on 'Boogie Man'

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here