Peter Jay

( economist, broadcaster, diplomat) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Born | 7 February 1937 London, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||

| Died | 22 September 2024 (Age 87) | |||||||||||||

| Nationality | UK | |||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Christ Church (Oxford) | |||||||||||||

| Children | 7 | |||||||||||||

| Spouse | • Margaret Callaghan • Emma Bettina Thornton | |||||||||||||

British journalist who was an early advocate for neoliberal economics. As ambassador, played tennis with Director of the CIA and Zbigniew Brzezinski.

| ||||||||||||||

Peter Jay was a British journalist who was an early advocate for neoliberal economics and was particularly influential in this regard during the 1970s. Along with his friend John Birt (the former Director-General of the BBC), Jay was also well known as an outspoken advocate of high brow analytical journalism – as opposed to the adversarial style (at least theoretically) favoured by current affairs journalists.

Contents

1937–67: Early life, education and civil service

Jay was born on 7 February 1937, the son of Douglas and Margaret (Peggy) Jay (née Garnett). Both his parents were Labour Party politicians although they came from privileged liberal, rather than socialist, backgrounds. The Observer describes Jay as being born to ‘Hampstead Royalty’. [1] Jay recalls that his father was an ‘egalitarian and a social reformer’ but was ‘passionately anti-Marxist’ and an imperialist who ‘thought the British Empire in its way, in its time, had been a glorious thing’. [2] In the 1960s he argued that the Labour Party should abandon nationalisation and its 'working class image'. [3]

Jay attended the Dragon school, a private prep school in Oxford, and then Winchester College, a prestigious private school attended by his grandfather, his father, and later his son. [4] After school he was in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as Midshipman and was promoted to Sub-Lieutenant. [5] He then attended Oxford University where he took a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics and was President of the Student Union. [6]

Jay later commented that despite focusing almost entirely on philosophy: ‘I subsequently passed myself off as an economist which was a bit of a cheek really because I rather neglected my economic studies when doing PPE.’ [7] At Oxford he was reportedly called ‘the cleverest young man in England’ by his Tutors, to which he responded: ‘Is there someone cleverer in Wales?’. [8]

After graduating in 1960, Jay took the Civil Service exam and in January 1961 joined the Treasury where he spent six years.[9] The couple had met at University and would divorce after a high profile separation on the late 1970s. [10]

1967–1977: Media, Monetarism and the ‘Mission to Explain’

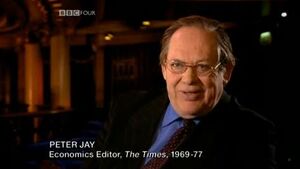

In 1967 Jay left the civil service to join The Times as its economics editor. He worked at the paper for ten years, during which time he was also associate editor of its business news. [11] Jay says his appointment was the result of a conversation with a BBC producer at a New Year’s Eve Party in 1966/7 (Jay’s wife was also a BBC producer). The producer asked if Jay had ever thought of being a journalist and the next day recommended him to William Rees-Mogg who had been appointed editor in waiting after a takeover of The Times. [12]

In the BBC documentary Tory! Tory! Tory! William Rees-Mogg states: ‘I asked him to join The Times, which he agreed to do and about a year later I asked him to go as the economic correspondent of The Times to the United States, because I felt that the economic weather was coming across the Atlantic and that if we covered what was happening in America we might get right what was going to happen next in Britain.’ [13] In the US, Jay was introduced to right-wing ‘free market’ economics by a friend from the British Embassy. Jay told the BBC his friend ‘had made it his job to get very close to the American economists including the Chicago based people, and he began to open my eyes to what the Chicago based people were saying; what Milton Friedman was saying…’ [14] Jay told the journalist and author Andy Beckett:

I visited the University of Chicago, the Hoover Institute in Standford, the Federal Reserve in St Louis, the great centres of monetarism... I met Friedman. He's a very attractive character. He has that wonderful Jewish humour and intellectuality. He became a good friend. [15]

Under the influence of the Chicago school, Jay came to believe that, in his words, ‘there was some kind of fundamental crisis in the assumptions on which economic policy had been up until then largely conducted. In which case a different approach, or something, was needed.’ [16] That ‘something’ turned out to be the political project now known as neoliberalism, which then tended to be referred to as ‘monetarism’ because of the movement’s focus at that time on the theoretical link between, unemployment, inflation and the money supply.

Along with Samuel Brittan at the Financial Times, Jay used his newspaper column to promote the new monetarist ideology in Britain. Recalling this period Brittan writes:

In the middle years of the 1970s, Peter Jay, who was then economic editor of The Times, and I were regarded by many in the British economic establishment as two terrible monetarist twins because of our scepticism of the Heath dash for growth… Jay and I had slightly different starting points. Nevertheless, unlike many purely technical monetarists, Jay never flinched from the implications of the new (or rediscovered) ideas on the ultimate futility of traditional full employment policies - witness his role in James Callaghan's famous speech to the 1976 Labour Conference in which the former Prime Minister delivered his much-cited speech about governments not being able to spend their way to prosperity. [17]

Brittan is here referring to the fact that Jay wrote portions of Callaghan's speech to the 1976 Labour Party conference, including a famous segment which stated:

We used to think that you could spend your way out of a recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting government spending. I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists, and in so far as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step.[18]

According to Jay he had originally penned a section of the speech which read: 'The way forward for socialists is... to change the role of labour so it becomes entrepreneurial,' and another early passage which pronounced that, 'Keynesianism has no future. [20] Though these passages were not included in the final speech, the speech as it was delievered is taken by some historians as the watershed which marks the end of the Keynesian post-war period and the beginning of the neoliberal period. In other words the point at which governments abandoned social democracy for a more explicitly right-wing and pro-business stance. On 10 December that year Milton Friedman told the BBC's Money Programme he thought the speech was a 'most hopeful sign' and 'one of the most remarkable talks - speeches - which any government leader has ever given.' [21]

An oft-repeated anecdote from Jay's period at The Times is an incident when a sub-editor said he found one of his articles difficult to follow. Jay replied: 'I only wrote this piece for three people – the editor of The Times, the Governor of the Bank of England, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer.' [22]

During this period at The Times, Jay also became involved in television. From 1972 to 1977 he was a presenter on LWT’s high brow current affairs programme Weekend World which was created by Jay’s friend, the future BBC Director-General, John Birt. Whilst at LWT, Jay and Birt developed a critique of television news and current affairs which appeared in a series of editorials printed in The Times in 1975/6. They argued that television had a ‘bias against understanding’ and that television producers should recruit journalists with special expertise and develop a more analytical style. What became known as the ‘mission to explain’ formed the intellectual rationale for a series of changes to BBC editorial practises in News and Current Affairs under John Birt. In 1977 after the Annan Committee criticised BBC News and Current Affairs, the BBC Chairman Michael Swann invited Jay and Birt to the BBC to give him their views on broadcasting. According to a member of the BBC management team quoted in The Battle for the BBC: 'The governors came quite close to the proposition that maybe we should bring these lads in and have them do a number on news and current affairs'. In the event the Director-General Charles Curran vetoed this suggestion but a paper was distributed to all the Governors detailing Jay and Birt's theory. [23]

During the 1970s Jay also fronted an ITV series called The Jay Interview. The programme ran for two series, each consisting of six hour long episodes broadcast late on Sunday evenings. The first series, on which John Birt worked as Executive Producer, was broadcast in 1975 and consisted of interviews with liberal intellectuals like the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, the Keynesian economist James Meade and the moral philosopher Bernard Williams. [24] The second series, broadcast in 1976 and produced by the then left wing journalist John Lloyd, consciously embraced more marginal figures. It was entitled ‘Alternatives to Liberal Democracy’ and included an interview with the anarchist intellectual Noam Chomsky and the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm. [25]

1977–1979: Ambassador to Washington

In 1977 Jay was appointed Ambassador to Washington by David Owen, the right-wing Labour Foreign Secretary who later split the party under Thatcher by co-founding the Social Democratic Party. According to Jay, Owen was suspicious of the senior Foreign Office officials and had come to believe that there was a ‘circle or network’ of civil servants from which he was excluded. Owen explained to Jay that ‘the only way he could be sure that some such exclusive network was not operating without his knowledge, was by appointing somebody whom he could, in this respect, completely trust to a key position in the network.’ [26] The appointment of Jay was highly controversial because of his marriage to the daughter of the Labour leader. [27]

Jay was posted to Washington from the summer of 1977 to the summer of 1979, staying on for a month after the Labour government was ousted by the Conservatives. According to Jay’s account he was removed as Ambassador because of the media’s expectation of a change under Thatcher. [28] During his time in Washington, Jay was tennis partners with US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski [29] as well as the then Director of the CIA and his successor:

The CIA was a most important relationship. I used to play tennis most mornings at seven o’clock, with Stan Turner, who was the Director of the CIA. We didn’t discuss very secret things over the tennis court, or over our breakfast afterwards, but it was an important relationship. And not only the CIA, but also the other shadowy agencies… Bill Webster was another tennis partner. He was the Director of the FBI before he became director of the CIA. But also agencies like the NSA and NPIC - all those sorts of organisations that are the equivalent of GCHQ. I don’t think we have an equivalent of NPIC. But NPIC was very important. [30]

1979–2009

In 1979 Jay joined the Economist Group as a consultant and from 1979 to 1983 was director of the Economist Intelligence Unit, the business intelligence firm affiliation with The Economist magazine. [31] From 1979 to 1980 he was also appointed a Visiting Scholar at the US think-tank the Brookings Institution. [32]

In 1980 Jay presented a series of studio discussions to accompany the broadcast of Milton Friedman’s neoliberal polemic Free to Choose. The 10-part television documentary was produced by the British company Video Arts Television after Friedman and his collaborator Bob Chitester had failed to find a production team in the US considered sufficiently sympathetic to their philosophy. [33] The BBC bought the rights to six of the programmes. [34] Five were broadcast with studio discussions with Milton Friedman hosted by Jay. [35]

In March 1980 Jay was approached by David Frost to head a bid for the ITV breakfast franchise. Jay agreed and headed what became TV-am until 1983 when he was forced to resign amid criticisms of his management style. [36] According to the Observer:

[Jay] won the franchise and launched the station with much ballyhoo about its 'mission to explain' and its Famous Five presenters (David Frost, Angela Rippon, Michael Parkinson, Anna Ford and Robert Kee). Viewers turned off in droves. A month after the launch, the ratings were down to 400,000 and Jay resigned, stabbed not in the back but in the front by his co-director and former friend Jonathan Aitken in a boardroom coup. Greg Dyke stepped in to save the station with Roland Rat. [37]

In 1981 Jay gave MacTaggart Memorial Lecture, the keynote address at the Edinburgh Television Festival and a highly prestigious platform in the world of British broadcasting. He said: 'We are within less than two decades technologically of a world in which there will be no technically based grounds for government interference in electronic publishing. Spectrum scarcity is going to disappear. There will be as many channels as there are viewers.' [38] Jay's technological determinism, and his vision of a consumer led broadcasting market, was echoed by other neoliberals in the broadcasting world like Rupert Murdoch and Andrew Neil, who (looking to expand into the British market) sought to portray deregulation and the end of public service broadcasting as an inevitable feature of the development of satellite and cable technologies.

From 1983 to 1986 Jay presented Channel 4’s weekly news programme A Week in Politics and from 1986 to 1989 was chief of staff to the press tycoon Robert Maxwell. [39] He also worked on the Chartered Institute of Bankers monthly magazine Banking World, as an Editor from 1984 to 1986 and a Supervising Editor until 1989. [40]

In 1985 Jay's 'terrible monetarist twin' [41] Sam Brittan was appointed to the Committee on Financing the BBC, better known as the Peacock Committee. This had been set up by the Thatcher government and was informed by the same neoliberal thinking on broadcasting that Jay and others had developed. Brittan wrote that he and the Committee's Chair Alan Peacock 'were inclined towards market provision of goods and services and... had been stimulated by Peter Jay's writings.' [42] Chris Horrie and Steve Clarke note that whilst the committee was conducting its inquiry, Samuel Brittan was in close contact with Jay:

Jay was not on the committee, but had strong thought of his own on the future of television. He and Brittan were to spend long sessions together at Jay’s Ealing home, effectively forming their own private committee, and wildly exceeding Peacock’s original brief. [43]

Jay also gave evidence to the Commission. According to the then Director-General Alisdair Milne, Jay was

the only individual invited to speak for himself, the Peacock guru. Peter set forth, at this usual machine-gun rate of delivery, his picture of the new world of electronic publishing, where programmes would pour out of the fibre-optic cables in the same way that books had poured off the presses in the past. Sam Brittan smiled like a Cheshire cat. [44]

After the Committee delivered its report in 1986, Brittan even suggested Jay as one of two possible future chairmen of the BBC. [45]

In 1990 Jay was appointed Economics Editor of the BBC by his old friend John Birt. Early on in this role he presented the Money Programme, but although he held the post until 2001, he kept a low profile during much of this time. The Observer reported in June 2000 that, 'colleagues complain that he has not been seen in his BBC office for years and that last time he appeared onscreen, for the Budget, he had to have a special briefing.' [46] That year Jay presented a a six-part BBC series on economic history called Road to Riches.

In 2003 he became a Director (non-executive) of the Bank of England. [47]

In June 2009 the Daily Mail reported that Jay was one of two members standing for the Chair of the Garrick Club, the exclusive London private members club which he had been invited to join by William Rees-Mogg 33 years earlier. [48] However, Jay was not elected, and lost to his only rival Jonathan Acton Davis QC. [49]

Family affairs

In 1961, Jay married Margaret Callaghan, daughter of the future Prime Minister Jim Callaghan, who was then the shadow chancellor, in a ceremony at the House of Commons’ crypt chapel. Peter and Margaret Jay had a son and two daughters together, but separated in 1986. After spending two years as British Ambassador in Washington from 1977 to 1979, the incoming Conservative government called time on Jay’s appointment. At that time it emerged that Margaret was having an affair with Carl Bernstein, the Washington Post journalist who helped expose the Watergate scandal.

The resulting breakdown of two marriages was immortalised in the novel "Heartburn" by Bernstein’s wife, Nora Ephron, and subsequently became a Hollywood film in 1986 starring Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson.[50]

Affiliations

Garrick Club [51] | Open Europe 'supporter'[52] |

References

- ↑ ‘Jay talking’, Observer, 18 June 2000

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber & Faber, 2009) p.337

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ ‘Jay talking’, Observer, 18 June 2000

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ ‘Jay talking’, Observer, 18 June 2000

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Tory! Tory! Tory!: The Outsiders, broadcast Friday, 10 August from 2340 BST on BBC Four.

- ↑ Tory! Tory! Tory!: The Outsiders, broadcast Friday, 10 August from 2340 BST on BBC Four.

- ↑ Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber & Faber, 2009) p.338

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Samuel Brittan, A professional autobiography, The 'Jay-Brittan' Period, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ quoted in 'Jim Callaghan: A life in quotes', BBC News Online, 26 March, 2005

- ↑ Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber & Faber, 2009) p.339

- ↑ Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber & Faber, 2009) p.339

- ↑ Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber & Faber, 2009) p.336

- ↑ quoted e.g. in Sebastian Shakespeare, 'Shakespeare’s Globe', New Statesman, 11 December 2008

- ↑ Steven Barnett & Andrew Curry, The Battle for the BBC: A British Broadcasting Conspiracy? (London: Aurum Press, 1994) p.79

- ↑ see BFI Film & TV Database, The JAY INTERVIEW, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ ‘Jay talking’, Observer, 18 June 2000

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Eileen Keerdoja, Jane Whitmore & Allan J. Mayer, 'Ambassador Jay', Newsweek, 15 May 1978; p.18

- ↑ Churchill College Cambridge, British Diplomatic Oral History Programme (BDOHP), Peter Jay interviewed on 24 February 2006 by Malcolm McBain, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Rose D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (University of Chicago Press, 1999) pp.475-6

- ↑ Rose D. Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (University of Chicago Press, 1999) p.499

- ↑ According to the BBC Motion Gallery the title of each segment and the date of its broadcast were as follows: Free to Choose:1:Power of Markets (16 February 1980); Free to Choose:2: The Tyranny of Control (23 February 1980); Free to Choose:3:Anatomy of Crisis (1 March 1980); Free to Choose:4: Created Equal (8 March 1980); Free to Choose:5: Who Protects the Consumer? (15 March 1980); Free to Choose:6: How to Cure Inflation (22 March 1980). All but Power of Markets, were broadcast with discussions hosted by Jay

- ↑ Moving Image Communications Ltd, TV-am Timeline [Accessed 22 October 2009]

- ↑ Peter Jay, ‘Jay talking’, Observer, 18 June 2000

- ↑ quoted in Owen Gibson, 'The foresight sagas', Guardian, 22 August 2005

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Samuel Brittan, A professional autobiography, The 'Jay-Brittan' Period, [Accessed 16 October 2009]

- ↑ quoted in Tom O'Malley, Closedown?: The BBC and Government Broadcasting Policy 1979-92 (London: Pluto Press, 1994) p.92

- ↑ Chris Horrie and Steve Clarke, Fuzzy Monsters – Fear and Loathing at the BBC (London: William Heinemann, 1994) p.37

- ↑ Alisdair Milne, DG: The Memoirs of a British Broadcaster (Hodder and Stoughton, 1989) p.224

- ↑ Peter Fiddick, 'The case for strong governors', Guardian, 9 September 1986. Brittan's other suggestion was the ITV presenter Alastair Burnet

- ↑ ‘Jay talking’, Observer, 18 June 2000

- ↑ Who's Who 2009, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2008 ‘JAY, Hon. Peter’, [accessed 16 Oct 2009]

- ↑ Richard Kay, 'The second coming of Peter Jay', Daily Mail, 9 June 2009; p.35

- ↑ Fiona Murray, Secretary to the Secretary, email to Tom Mills, 29 January 2010 17:32

- ↑ "Peter Jay, journalist and diplomat, dies aged 87"

- ↑ Debrett's People of Today (Debrett's Peerage Ltd, January 2009) [Accessed via KnowUK on 15 October 2009]

- ↑ Open Europe 2005-2007Supporters Accessed 22 Aug 2007

powerbase is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here