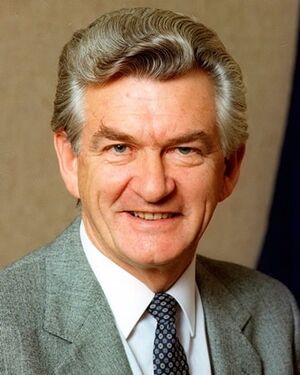

Bob Hawke

( Trade Union leader, Politician, deep state operative) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Robert James Lee Hawke 1929-12-09 Bordertown, South Australia, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 May 2019 (Age 89) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | • University of Western Australia • University College (Oxford) • Australian National University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | • Arthur Hawke • Edith Lee | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Hazel Masterson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of | Rhodes Scholar/1953 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Labor Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | • Albert Hawke • John Hawke • See • Hawke family | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Australian Prime Minister and informant to US services.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bob Hawke was Australian PM from 1983-1991 for the Labor party.

It has long been known that he was a US intelligence informant for many years.[1] Apart from his murky role during the 1975 coup against the Labor government, this clandestine relationship had a major impact on Australian politics when he later became PM, both economically, with the inauguration of the era of neoliberalism, and military, securing the US military grip in the region.

Contents

"The ideal Australian Labour leader'

The US diplomats early saw much “potential value” in Hawke as a “possible future Labour leader and prime minister".[1]

While serving as leader of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), and President of the Labor party, the man who would later be known as the “people’s Prime Minister” passed on sensitive information about the government, the trade union movement and more to Washington over many years. He provided a regular flow of “reliable” intelligence to prove he could be depended upon, including advance warning and insider information on planned strikes and industrial action by workers at major US corporations operating in Australia.[1]

He also reported on meetings conducted abroad with influential figures and groups, including the UK Labour Party. Hawke was, presumably unknowingly, surveilled closely by US intelligence throughout these trips.[1] The precise points at which Hawke’s secret spell as an informant commenced and ended aren’t known, but documents[2] analyzed by Cameron Coventry go from 1973 to 1979, and include the time of the 1975 coup against Labor PM Gough Whitlam.

A May 1974 diplomatic cable states:

I wish to emphasise how important proposed visit of Bob Hawke to US can be...There is little doubt that he has major potential...he has every prospect of being a major figure on political scene for next 20 years or so, and it will be worth our while to make a real effort to develop a worthwhile program for him}[1]

Three months later, another cable spoke glowingly of Hawke, predicting confidently that he would eventually be transformed into the “ideal Australian Labour leader”[1]

Feeling he would “benefit from being exposed to some sophisticated non-labour thinking on the role of multinationals in Australian economic development,” it was proposed he be invited to Washington to meet representatives of Chase Manhattan Bank, the International Chamber of Commerce, Brookings Institution, and other organisations and be educated in the merits of the then-burgeoning doctrine of neoliberalism[1].

Education and early career

Hawke was educated at the University of Western Australia, graduating in 1952 with a Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws. He was also president of the university's guild during the same year.[3] The following year, Hawke won a Rhodes Scholarship to attend University College, Oxford, where he undertook a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE).[4] He soon found he was covering much the same ground as he did in his education at the University of Western Australia, and transferred to a Bachelor of Letters. He wrote his thesis on wage-fixing in Australia and successfully presented it in January 1956.[5]

His academic achievements were complemented by setting a new world record for beer drinking; he downed 2 1⁄2 imperial pints (1.4 l)—equivalent to a yard of ale—from a sconce pot in 11 seconds as part of a college penalty.[6][7] In his memoirs, Hawke suggested that this single feat may have contributed to his political success more than any other, by endearing him to an electorate with a strong beer culture.[5]

In 1956, Hawke accepted a scholarship to undertake doctoral studies in the area of arbitration law in the law department at the Australian National University in Canberra.[5][8] Soon after his arrival at ANU, Hawke became the students' representative on the University Council.[8] A year later, Hawke was recommended to the President of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) to become a research officer, replacing Harold Souter who had become ACTU Secretary. The recommendation was made by Hawke's mentor at ANU, H.P. Brown, who for a number of years had assisted the ACTU in national wage cases. Hawke decided to abandon his doctoral studies and accept the offer, moving to Melbourne with his wife Hazel[9]

Not long after Hawke began work at the ACTU, he became responsible for the presentation of its annual case for higher wages to the national wages tribunal, the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. He was first appointed as an ACTU advocate in 1959. The 1958 case, under previous advocate R.L. Eggleston, had yielded only a five-shilling increase.[10] The 1959 case found for a fifteen-shilling increase, and was regarded as a personal triumph for Hawke.[11] He went on to attain such success and prominence in his role as an ACTU advocate that, in 1969, he was encouraged to run for the position of ACTU President, despite the fact that he had never held elected office in a trade union.[12] He was elected ACTU President in 1969 on a modernising platform by the narrow margin of 399 to 350.

Member of Parliament

Hawke's first attempt to enter Parliament came during the 1963 federal election. He stood in the seat of Corio in Geelong bu fell short of winning.[13] Hawke rejected several opportunities to enter Parliament throughout the 1970s, something he later wrote that he "regretted". He eventually stood for election to the House of Representatives at the 1980 election for the safe Melbourne seat of Wills, winning it comfortably. Immediately upon his election to Parliament, Hawke was appointed to the Shadow Cabinet by Labor Leader Bill Hayden as Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations.[14]

Hayden, after having narrowly lost the 1980 election, was increasingly subject to criticism from Labor MPs over his leadership style. In order to quell speculation over his position, Hayden called a leadership showdown on 16 July 1982, believing that if he won he would be guaranteed to lead Labor through to the next election.[15] Hawke decided to challenge Hayden in the showdown, but Hayden defeated him by five votes; the margin of victory, however, was too slim to dispel doubts that he could lead the Labor Party to victory at an election.[16] Despite his defeat, Hawke began to agitate more seriously behind the scenes for a change in leadership, with opinion polls continuing to show that Hawke was a far more popular public figure than both Hayden and Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. Hayden was further weakened after Labor's unexpectedly poor performance at a by-election in December 1982 for the Victorian seat of Flinders, following the resignation of the former Liberal MP Phillip Lynch. Labor needed a swing of 5.5% to win the seat and had been predicted by the media to win, but could only achieve 3%.[17]

Labor Party power-brokers, such as Graham Richardson and Barrie Unsworth, now openly switched their allegiance from Hayden to Hawke.[17] More significantly, Hayden's staunch friend and political ally, Labor's Senate Leader John Button, also started to support Hawke.[18] Less than two months after the Flinders by-election result, Hayden announced his resignation as Leader of the Labor Party on 3 February 1983. Hawke was subsequently elected as Leader unopposed, and became Leader of the Opposition in the process.[18] Having learned that morning about the possible leadership change, on the same that Hawke assumed the leadership of the Labor Party, Malcolm Fraser called a snap election for 5 March 1983, unsuccessfully attempting to prevent Labor from making the leadership change.[19] However, he was unable to have the Governor-General confirm the election before Labor announced the change.

At the 1983 election, Hawke led Labor to a landslide victory, achieving a 24-seat swing and ending seven years of Liberal Party rule.

Prime Minister of Australia

Economic policy

The Hawke Government oversaw significant economic reforms, and is often cited by economic historians as being a "turning point" from a protectionist, model based on agriculture and industry to a more globalised and services-oriented economy. According to the journalist Paul Kelly, "the most influential economic decisions of the 1980s were the floating of the Australian dollar and the deregulation of the financial system".[20] Although the Fraser Government had played a part in the process of financial deregulation by commissioning the 1981 Campbell Report, opposition from Fraser himself had stalled this process.[21] Shortly after its election in 1983, the Hawke Government took the opportunity to implement a comprehensive program of economic reform, in the process "transform(ing) economics and politics in Australia".[20]

Hawke and Treasurer Keating together led the process for overseeing the economic changes by launching a "National Economic Summit" one month after their election in 1983, which brought together business and industrial leaders together with politicians and trade union leaders; the three-day summit led to a unanimous adoption of a national economic strategy, generating sufficient political capital for widespread reform to follow.[22] Among other reforms, the Hawke Government floated the Australian dollar, repealed rules that prohibited foreign-owned banks to operate in Australia, dismantled the protectionist tariff system, privatised several state sector industries, ended the subsidisation of loss-making industries, and sold off part of the state-owned Commonwealth Bank.[23]

Foreign policy

The Hawke Government pursued a close relationship with the United States, assisted by Hawke's close friendship with US Secretary of State George Shultz; this led to a degree of controversy when the Government supported the US's plans to test ballistic missiles off the coast of Tasmania in 1985, as well as seeking to overturn Australia's long-standing ban on uranium exports. Although the US ultimately withdrew the plans to test the missiles, the furore led to a fall in Hawke's approval ratings.[24] Shortly after the 1990 election, Hawke would lead Australia into its first overseas military campaign since the Vietnam War, forming a close alliance with US President George H. W. Bush to join the coalition in the Gulf War. The Australian Navy contributed several destroyers and frigates to the war effort, which successfully concluded in February 1991, with the expulsion of Iraqi forces from Kuwait.

Arguably the most significant foreign policy achievement of the Government took place in 1989, after Hawke proposed a south-east Asian region-wide forum for leaders and economic ministers to discuss issues of common concern. After winning the support of key countries in the region, this led to the creation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). The first APEC meeting duly took place in Canberra in November 1989; the economic ministers of Australia, Brunei, Canada, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and the United States all attended. APEC would subsequently grow to become one of the most pre-eminent high-level international forums in the world, particularly after the later inclusions of China and Russia, and the Keating Government's later establishment of the APEC Leaders' Forum.[25]

Retirement and later life

After leaving Parliament, Hawke entered the business world, taking on a number of directorships and consultancy positions which enabled him to achieve considerable financial success.

Bibliography

- Anson, Stan (1991). Hawke: An Emotional Life. Macphee Gribble.

- Blewett, Neal (2000), 'Robert James Lee Hawke,' in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland, Sydney, New South Wales, pages 380–407. ISBN 1-86436-756-3

- Bramston, Troy; Ryan, Susan (2003). The Hawke Government : A Critical Retrospective. Pluto. ISBN 1-86403-264-2.

- d'Alpuget, Blanche (1982). Robert J Hawke. Schwartz. ISBN 0-86753-001-4.

- Davidson, Graham; Hirst, John; MacIntyre, Stuart (1998). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553597-9.

- Edwards, John (1996). Keating, The Inside Story. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026601-1.

- Hawke, Bob (1994). The Hawke Memoirs. Heinemann. ISBN 0-85561-502-8.

- Hurst, John (1983). Hawke PM. Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-14806-6.

- Jaensch, Dean (1989). The Hawke-Keating Hijack. Allen and Unwin. ISBN 0-04-370192-2.

- Kelly, Paul (1992). The End of Certainty: The story of the 1980s. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-227-6.

- Mills, Stephen (1993). The Hawke Years. Viking. ISBN 0-670-84563-9.

- Richardson, Graham (1994). Whatever It Takes. Bantam. ISBN 1-86359-332-2.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c d e f g https://www.rt.com/op-ed/527804-bob-hawke-australia-us-intelligence/

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341655929_The_%27Eloquence%27_of_Robert_J_Hawke_United_States_informer_1973-79

- ↑ http://www.news.uwa.edu.au/201403276544/features/bob-hawke-qualifies-cheap-coffee-campus

- ↑ Hawke, Bob (1994), p.24

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c Hawke, Bob (1994), p. 28

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=M7ByAAAAMAAJ&q=The+Hawke+Memoirs

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20100507172230/http://mediaman.com.au/articles/spiffing.html%7C

- ↑ Jump up to: a b Hurst, J., (1983), p.25

- ↑ Hurst, J., (1983), p. 26

- ↑ Hurst (1983), p. 27

- ↑ Hurst (1983), p. 31

- ↑ Bramble, Tom (2008). Trade Unionism in Australia: A History from Flood to Ebb Tide. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20121010223600/http://psephos.adam-carr.net/countries/a/australia/1963/1963repsvic.txt

- ↑ Hurst, J., (1983), p. 262

- ↑ Kelly, P., (1992), p. 24

- ↑ Hurst, J., (1983), p. 269

- ↑ Jump up to: a b Hurst, J., (1983), p. 270

- ↑ Jump up to: a b Hurst, J., (1983), p. 273

- ↑ Hurst, J., (1983), p. 275

- ↑ Jump up to: a b Kelly, P., (1992), p.76

- ↑ Kelly, P., (1992), p.78

- ↑ https://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2011/s3400566.htm

- ↑ http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22library%2Fpartypol%2F1052410%22

- ↑ https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/us-rocket-plan-became-hawkes-first-setback-20121231-2c2ia.html

- ↑ https://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC/History