John Crawford

( policeman, author) | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1945 |

A detective constable who played a leading part in investigating the sabotage of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie. | |

John Crawford was born in Glasgow at the end of World War II, worked as a miner, and then served in the Royal Navy. In 1971, he joined the Scottish Police and served for over 29 years, most of those as a detective.

Detective Constable Crawford played a leading part in investigating the sabotage of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988, and wrote a book about the experience: "The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale", which was published on 13 August 2002 (six months after Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's appeal against conviction had been rejected). On pages 88/89, DC Crawford wrote:

"We even went as far as consulting a very helpful lady librarian in Newcastle who contacted us with information she had on Bernt Carlsson. She provided much of the background on the political moves made by Carlsson on behalf of the United Nations. He had survived a previous attack on an aircraft he had been travelling on in Africa.

It is unlikely that he was a target as the political scene in Southern Africa was moving inexorably towards its present state. No matter what happened to Carlsson after he had completed his mission in Namibia the political changes were already well in place and his demise would not have altered anything. This would have made a nonsense of any alleged assassination attempt on him as it would not have achieved anything. I discounted the theory as being almost totally beyond the realms of feasibility.

We eventually produced a report on all fifteen [the 'first fifteen' of the interline passengers] to the SIO (John Orr), each person had their own story and as many antecedents as we could gather. The other teams had also finished their profiles of their group of interline passengers. None of them had found anything which could categorically put any of the interline passengers into any frame as a target, dupe or anything else other than a victim of crime."[1]

Contents

The Met dispatched

John Crawford describes in "Chapter Three – The Investigation" (pages 70/71) how officers from the Metropolitan Police were excluded from investigating the Lockerbie bombing in Scotland and dispatched home to London.

It was hopefully time for me to get involved in the enquiry proper.

I knew that a considerable amount of political in-fighting had been going on from day one. The Metropolitan Police Anti-Terrorist squad from London had tried to make the enquiry theirs from the first day. There was considerable opposition to this both politically and from the Scottish police.

Scotland Yard as any ordinary cop knows was like living on a reputation built 100 years ago. Sure it had the facilities to conduct a huge enquiry; sure it had the personnel and was supposed to have the expertise. It certainly had the resources in manpower and finance. But ask a cop in any force up and down the country who they consider the most arrogant, the most useless and the least likely to do anything for anyone beyond their 'patch' and they will undoubtedly tell you – The Met.

It's an unfortunate reputation because I personally know of a number of fine officers in that organisation who would match the best anywhere. But the reputation of the Met precedes it and it does not enjoy the high standing it thinks it does in what it disparagingly calls the 'provincial' forces. I would like to think things have changed since then but I rather think they have not.

No – neither the Scottish police nor the Lord Advocate Lord Fraser of Carmylie wanted them messing around in our enquiry. It was said the Lord Advocate presented an ultimatum to the then Prime Minister, the Iron Lady herself, Margaret Thatcher that either he was in charge of the enquiry as befitted his role as Lord Advocate in Scotland or he would resign. I cannot vouch for the veracity of that but as far as the Met Anti-Terrorist squad were concerned it was all over. They were hanging around for a few days with their flashy designer suits and the full weight of their own egos and self-importance on their shoulders, the once deserved reputation of Scotland Yard expected to sweep all before them.

After all, what could a bunch of hick 'jocks' do, we were experts only in dealing with sheep and haggis – let's face it, according to them nothing of any consequence ever happened outside London.

The Met were told in no uncertain manner that they weren't welcome! It was back to London for them.

Thereby Hangs A Tale

This is a longer extract from "The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale" (pages 79/89):

The enquiry team personnel were reorganised once again and I found myself working with Alex Brown, a DS from Carluke in Lanarkshire.... Just after being set up in this format we were told that a team of us would form the Priority Profiling team. Both Alex and I would be responsible for taking a close look at all of the so-called 'first fifteen' of the interline passengers: those most likely to have been targeted or of some status that would make them a possible target.

All fifteen had boarded Pan Am 103 from another flight and therefore had their luggage checked through an airport other than Frankfurt or Heathrow. Our task was to examine every aspect of the person, obtain as much background as possible, examine every detail we could find and eliminate them from further enquiry as a target or possible 'stooge' who had been tricked into carrying anything on board. Another four groups were dealing with other interline passengers.

The people we had to profile were:

- Michael Bernstein - A Nazi hunter who was employed by the US State Department and was returning from a job in Austria to the USA.

- Bernt Carlsson - A United Nations Commissioner who was heavily involved in negotiations regarding the independence of South-West Africa (Namibia).

- Richard Cawley - An American businessman with no known links with any State function.

- Joseph Patrick Curry - A 31 year old Special Forces captain who had been attending an international security conference in Italy.

- Robert Fortune - Another American businessman, again no links with any State authority.

- James Fuller - Vice President of Volkswagen in America returning to the US - no links with any State authority.

- Matthew Gannon - A US State official who had been operating in Beirut.

- Ronald La Riviere - Another US State official who had been operating in Beirut and who had travelled from there to Cyprus with Gannon and McKee in a military helicopter.

- Charles 'Tiny' McKee - A Major in the US Army working in Beirut. A 40 year old communications and code specialist, he had travelled to Cyprus with Gannon and La Riviere.

- Louis Marengo - Marketing director of Volkswagen in the US. Along with his fellow senior executive James Fuller, Marengo was returning home from a business trip. He had no links with any State authority.

- Daniel O'Connor - Another US State official who was responsible for security at the American embassy in Cyprus. He had flown from Cyprus in company with Gannon, La Riviere and McKee.

- Robert Pagnucco - An American businessman returning from a business trip in Europe. No links with State authority.

- Peter Pierce - A US citizen returning from a postgraduate course in Italy.

- Arnaud Rubin - A Belgian national who was returning from a holiday at his parents' home in Belgium to his work in America.

- James Stow - An Englishman living in New York. He had been in Switzerland on a business trip.

- Elia Stratis - Another American businessman returning home from a trip. No links with any State authority.

It was not an easy task establishing all we wanted to know about each. We confirmed very quickly that the businessmen identified were just that.

We asked the FBI to make certain enquiries in the US on our behalf to establish antecedents for all our subjects. Some of the agents were slow on the uptake and seemed reluctant to carry out enquiries. They couldn't see the point of investigating someone who was patently innocent. That was our first wee sign that each investigating force had its own methods of investigation.

In Scotland we gather as much information as possible about a murder victim in an attempt to ensure that there are no skeletons lurking that might have had some effect on the crime. We never leave any stone unturned - it might conceal an all-important clue. Each fact must be examined from all angles and then filed away for any future reference that may be required.

We double then triple check everything. I suppose we have less murders to investigate than some other countries and we still place a great deal of importance on investigating them. Resources that are given over to murder enquiries in Scotland are simply not available in places where hourly murders occur. I thank God that we still value human life enough to devote the necessary resources to investigating all murders fully. Signs are this will not always be the case as more and more accountants are hitched to the police, checking every single penny spent.

I had never experienced working with the Federal Bureau of Investigation before Lockerbie. Of course I'd heard of them even if they'd never heard of us! They were, it was said, the investigators supreme; I looked forward to learning from the experience. The first paperwork we got back from the US was what the FBI called a FD402 - these are the statements made up from the interviews carried out by the FBI personnel.

I read one incredulously: it began with the two FBI agents going to the home of the relative of one of the deceased. The first part of the report was about how pleased the people were that the FBI were investigating the Lockerbie bombing, with little real information other than that added. It may well be that the family was grateful that the FBI were lending their considerable experience and expertise to the enquiry. But there was no real need to fill out the FD402 report with an advertisement for the agency - there was nothing evidential to be gained either negatively or positively from that little gem. It was a disappointment.

The reports that were starting to come through to the rest of the enquiry were often the same. They were either very good with lots of information or they were utter rubbish that was fit only for file 13 (the rubbish bin). I was willing to forget the bad ones, no investigating force has a perfect set of agents. There are always one or two who can hardly write their name, never mind a report containing the information requested.

We weren't the only ones complaining about the poor standards. The other teams had their moans, so one of the Inspectors from the HOLMES team went to the States to get some relevant answers for us. David Isles was an Englishman who worked for Strathclyde. He returned promptly and we all gathered for a briefing. He said in his northern English accent:

- "The first thing that you have got to realise is that the Americans are different!"

I was flabbergasted. This guy had gone over to the States and thought fit to relate that the "Americans were different" - well we took that little diamond right to heart, imagine the Americans being different from us we mused. Whatever next! His trip had been a waste of time as far as we were concerned. The same old problems remained and were never satisfactorily sorted out.

While investigating James Ralph Stow, we turned up a guy in London who knew him well; according to his friend Mr Stow had been in Switzerland meeting with the son-in-law of the Venezuelan president. Apparently the president was trying to sell off parts of his country to the Americans without his people knowing what he was up to. It seemed a far-fetched story at the time but we took details of it nevertheless. We knew that Stow was an international banker who was a bit of a wheeler and dealer and the friend seemed genuine enough. We passed on the information we had obtained but never heard anything more about it.

Alex Brown and I eventually got fifteen fat files of information on our subjects. A few had proved very interesting - particularly those four US State Department officials who had travelled on the same flight from Cyprus.

All the theories about warnings that have been aired since the disaster (especially the so-called Helsinki Warning) that had been circulated to all the American embassies warning personnel not to travel on this particular flight seems to be a nonsense. Unless the American embassy in Cyprus was not on the address list of the warning nor, it would seem any embassy that looked after American interests in Beirut. I'm afraid that I hold no confidence in these so-called alarms that were raised. The passengers and crew were unfortunate in the extreme to have been made a target for a strike against the United States. In any case we dug up as much as possible but many questions were left unanswered about the four Americans who flew from Cyprus. They had some strange connections and were obviously working for their government in Lebanon. We were forced to make decisions on the information we had to hand. It is unlikely that any of the four would have been unprofessional enough to have had a bomb put into their baggage either in Beirut or in Cyprus before they caught their flight to London to pick up Pan Am 103. All four were professionals in their trade and I don't believe that they could have been duped.

We even went as far as consulting a very helpful lady librarian in Newcastle who contacted us with information she had on Bernt Carlsson. She provided much of the background on the political moves made by Carlsson on behalf of the United Nations. He had survived a previous attack on an aircraft he had been travelling on in Africa. It is unlikely that he was a target as the political scene in Southern Africa was moving inexorably towards its present state. No matter what happened to Carlsson after he had completed his mission in Namibia the political changes were already well in place and his demise would not have altered anything. This would have made a nonsense of any alleged assassination attempt on him as it would not have achieved anything. I discounted the theory as being almost totally beyond the realms of feasibility.

We eventually produced a report on all fifteen to the SIO, each person had their own story and as many antecedents as we could gather. The other teams had also finished their profiles of their group of interline passengers. None of them had found anything which could categorically put any of the interline passengers into the frame as a target, dupe or anything else other than a victim of crime.

Notes:

- 1. DC Crawford's Priority Profiling list of interline passengers (the 'first fifteen') actually totals sixteen names.

- 2. The SIO (Senior Investigating Officer) mentioned in the final paragraph of the extract is the former Detective Chief Superintendent John Orr of the Lockerbie Incident Control Centre.

- 3. On 24 August 2009, in an article published in The Scotsman, both Orr's successor as SIO Stuart Henderson and the book's author, DC John Crawford, were highly critical of Scottish Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill's decision to grant compassionate release to Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi.

Critic of Kenny MacAskill

Following the release on 20 August 2009 from prison in Scotland of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi who was convicted in 2001 of the Lockerbie bombing, John Crawford joined Stuart Henderson in criticising Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill:

- "I think the compassion angle was all wrong. It was inevitable that people would use it against the decision he made as it was so obvious that Megrahi did not show one jot of compassion when he cold bloodedly went about his business of killing 270 innocent people."[2]

Petition to PM Gordon Brown

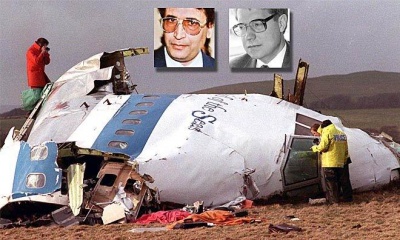

In October 2009, former diplomat Patrick Haseldine sent this petition to PM Gordon Brown: "We the undersigned petition the Prime Minister to endorse calls for a United Nations Inquiry into the murder of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing."

- Sweden's UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, was the most prominent of the 270 Lockerbie bombing victims murdered on 21 December 1988.

- In investigating Carlsson's murder, Scottish police detective John Crawford stated in his book ("The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale"):

- "We even went as far as consulting a very helpful lady librarian in Newcastle who contacted us with information she had on Bernt Carlsson. She provided much of the background on the political moves made by Carlsson on behalf of the United Nations. He had survived a previous attack on an aircraft he had been travelling on in Africa. It is unlikely that he was a target as the political scene in Southern Africa was moving inexorably towards its present state....I discounted the theory as being almost totally beyond the realms of feasibility."

- A United Nations Inquiry can be expected to find a different - and much better - explanation for Bernt Carlsson's murder.[3]

Lockerbie 'first fifteen'

On 11 February 2010, George Burgess (Deputy Director of the Scottish Justice Directorate) emailed former diplomat Patrick Haseldine:

- "You ask for an extract of the 'first fifteen' report referred to in John Crawford’s book. As I am sure you are aware, the Scottish Government itself is not involved in the conduct of criminal investigations. That responsibility lies with the police, under the direction of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. There is therefore no reason why we would have a copy of the 'first fifteen' report. I suggest that you contact Dumfries & Galloway Constabulary or the Crown Office."

On 8 November 2013, Patrick Haseldine emailed Detective Chief Superintendent Stuart Henderson to request an extract of the 'first fifteen' report (dealing specifically with interline passenger Bernt Carlsson) which Wikispooks will publish:

- "Dear DCS Stuart Henderson,

- "As Senior Investigating Officer of the Lockerbie criminal investigation, you received reports from teams of police investigators on the interline passengers who joined Pan Am Flight 103 on 21 December 1988 from other airlines.

- "Detective Constable John Crawford submitted to you a report on the 'first fifteen' of these interline passengers, who included United Nations Assistant Secretary-General Bernt Carlsson.

- "According to Swedish journalist, Jan-Olof Bengtsson, Bernt Carlsson arrived at Heathrow from Brussels on British Airways flight BA391 at 11.06am. Mr Carlsson was apparently driven to London for a pre-arranged meeting with the diamond mining and marketing firm De Beers, and returned to Heathrow in good time to catch the doomed flight.

- "I should be grateful if you could email me an extract of DC Crawford's 'first fifteen' report that deals specifically with interline passenger Bernt Carlsson.

- "Yours sincerely,

- "Patrick Haseldine

- "PS. (Monday, 11 November 2013, 10:00) Further research reveals that DC Crawford lists sixteen names in his 'first fifteen' report."

Review by Dr John Cameron

On 15 May 2012, in an Amazon book review headed "The Lockerbie Incident: the endless disquiet", Dr John Cameron wrote:

John Crawford demands closure but huge doubts remain about the prosecution's case and the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) in 2007 found prima facie evidence of a miscarriage of justice. Their report makes plain that the gross unreliability of the prosecution's key witness Tony Gauci is one of the main reasons for the referral of Megrahi's case back to the Appeal Court. Gauci was interviewed 17 times by Scottish and Maltese police during which he gave a series of inconclusive statements and there is clear evidence that leading questions had been put to him. Gauci was obviously not the "full shilling" (as Lord Fraser, Scotland's senior law officer in the investigation, later admitted) and yet the US paid him $2 million for his 'revised identification'.

The theory that the bomb entered the system in Malta as a piece of unaccompanied baggage and rattled around Europe before finding its way onto Pan Am 103 in London has been rightly ridiculed. In fact, not only was there no evidence that the bomb had been put on board in Malta, but Air Malta had won a libel action in 1993 establishing that it was not! The evidence linking Megrahi to the atrocity is so fragile, so complex and so full of unsupported assumptions it depends almost totally upon the integrity of the forensic scientists. It is therefore unfortunate that it would be difficult to find practioners of the science with more dodgy track records than the three involved in this investigation: Alan Feraday, Thomas Hayes and Thomas Thurman. It should be a matter of deep concern that Megrahi is the only man convicted on the evidence of these three individuals whose conviction was not reversed on appeal.

The review commission also discovered that the prosecution failed to disclose contrary evidence to the defence including a document from a foreign power which confirmed beyond any shadow of a doubt that the bomb timer was supplied to countries other than Libya. This document, passed to the commission by the foreign power in question, contained considerable detail about the method used to conceal the bomb and linked it to the PFLP-GC, the first suspects in the investigation. Moreover, the Iranian defector Abolghasem Mesbahi, who provided intelligence for the Germans, had already told the prosecutors in 1996 that the bombing been ordered by Tehran, not Tripoli.

There is also no credible evidence that the clothes from Tony Gauci's shop found among the Lockerbie wreckage were bought on the day stated in the trial. The sale seemed much more likely to have happened on a day when Abu Talb was on Malta and Megrahi was not. It is also known that when the Swedish police arrested Abu Talb for a different terrorist offence they found some of the same batch of clothing in his flat in Uppsala.

Lamin Khalifah Fhimah walked, not because the case against him was less water-tight than that against Megrahi but because he was defended by Richard Keen, Scotland's leading advocate, who shredded the evidence of ALL the prosecution's witnesses.

Finally the behaviour of the chief prosecutor, both in concealing the forensic scientists' deplorable record and withholding essential evidence, was utterly reprehensible. It left a stain on the reputation of the entire Scottish legal system.[4]

Remembering Lockerbie

Marking the 20th anniversary of the Lockerbie bombing, John Crawford was interviewed by The Scotsman newspaper:

John Crawford has no time for conspiracy theorists. He is impatient with those who claim that the fragment of the bomb timing mechanism discovered embedded in a scrap of cloth at the Pan Am 103 crash site was fabricated. And he dismisses as "nonsense" the claims that Tony Gauci, the Maltese who identified Abdelbaset al-Megrahi as the man who purchased from his shop the clothes that were packed into a suitcase with the bomb, is an unreliable witness.

"It pisses me off when people say Megrahi is innocent," he says. "That makes a mockery of all the work we did to make sure he ended up in court. If we hadn't done it, nobody else would have. The Americans would have had him shot somewhere. But we made him face justice."

A retired police officer, 63-year-old Crawford now works as a private investigator in the north-east of Scotland. But for several years he was part of the Lockerbie inquiry. A detective with the Lothian and Borders force, he was woken at 3am on December 22, 1988, and told to report for duty pronto. He and his colleagues found Lockerbie "a sea of flashing blue lights" and set to work recovering bodies.

"They were scattered about like a battlefield. It was a case of gritting your teeth and getting on with it. The target was getting all the bodies recovered by Christmas Day, and that happened."

He remembers every body he lifted. Although the recovery operation was on an industrial scale, he never forgot that these were human beings and deserved to be treated with as much dignity as possible. Later, he learned the names of the people he found, and a bit about their lives. The hardest thing was picking up toys. When he closes his eyes he can still see the name of Rachael Stevenson, which along with the names of all the other victims was written on the wall of the inquiry room; she was eight, the same age as his daughter, and had been travelling with her parents and big sister.

Crawford was honoured when he was asked to join the investigation proper. His work would take him to Sweden, Jordan, Libya and especially to Malta, where he spent 18 months investigating the clothes known to have been in the suitcase with the bomb. He was sitting beside Gauci when he identified Megrahi from a line-up of a dozen photographs. He was elated then, and ecstatic when Megrahi was found guilty.

The inquiry left its mark on Crawford. He developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); mostly, he thinks, from fretting that any of the many flights he took to the UK from Malta might be blown up by terrorists targeting the police. No regrets, though?

"No. I'll go to my grave knowing that I and the rest of the guys did the very best we could."[5]

See also

- Cameron's Report on Lockerbie Forensic Evidence

- The Framing of al-Megrahi

- The How, Why and Who of Pan Am Flight 103

References

- ↑ "The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale"

- ↑ "Lockerbie detective: MacAskill was naive"

- ↑ Endorse calls for a United Nations Inquiry into the murder of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing

- ↑ "The Lockerbie Incident: the endless disquiet"

- ↑ "Remembering Lockerbie"