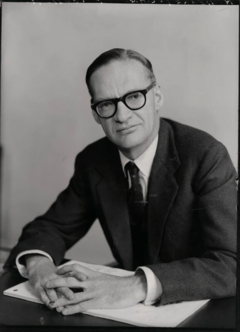

Harold Beeley

( academic, diplomat, historian) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 February 1909 |

| Died | 27 July 2001 (Age 92) |

| Alma mater | The Queen's College (Oxford) |

| Children | |

| Spouse | • Millicent Chinn • Karen Beeley |

Sir Harold Beeley was a British diplomat, historian, and Arabist. After beginning his career as a historian and lecturer, following World War II, Beeley joined HM Diplomatic Service and served in posts and ambassadorships mainly related to the Middle East. He returned to teaching after retiring as a diplomat.[1]

Contents

Early life and academia

Harold Beeley was born in Manchester, England to an upper middle-class London merchant in 1909, and studied at Highgate School and The Queen's College, Oxford, gaining a First in Modern History. He began his career in academia; from 1930 he taught modern history as an assistant lecturer at University of Sheffield, and the next year he moved to University College London also as an assistant lecturer. In 1935, he was appointed as a junior research fellow and lecturer at The Queen's College, Oxford and, during 1938 to 1939, Beeley lectured at University of Leicester. During his academic career, he wrote a short biography on British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli which was one of a series of Great Lives biographies published by Duckworth in 1936.

Beeley did not serve in the British armed forces during World War II because of his poor eyesight. Instead, he worked at Chatham House with Arnold Toynbee in 1939; he subsequently joined the Foreign Office's Research Department, and he finally worked on the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945, where he helped design the UN Trusteeship Council along with Ralph Bunche.

Before becoming a diplomat, Beeley was chosen to serve as Secretary of the Anglo-American Commission of Inquiry on Palestine in 1946. Beeley believed then and afterward that the founding of Israel would forever complicate relations between the United Kingdom and the Middle East, resulting in an enduring dislike of Beeley among leading Zionists and the Jewish Agency. According to the New York Times, his views on the issue may have helped persuade Ernest Bevin to try to limit Jewish immigration to the region.

Diplomatic career

In 1946, Beeley officially joined Her Majesty's Diplomatic Service, which at his age was later than most. His first posting was as assistant in the geographical department responsible for Palestine, which led him to advise Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin. Together with Bevin, he negotiated the Portsmouth Treaty with Iraq (signed on 15 January 1948), which was accompanied by a British undertaking to withdraw from Palestine in such a fashion as to provide for swift Arab occupation of all its territory.

Portsmouth Treaty

According to then-Iraqi foreign minister Muhammad Fadhel al-Jamali:

At the appointed hour Mr Bevin arrived with Mr Creech Jones, Secretary for the Colonies, Mr Michael Wright, Director of the Near East Section of the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sir Henry Mack, British Ambassador to Iraq, and Mr Harold Beeley, specialist on Palestine in the Foreign Office.

Mr Bevin opened the discussion saying, "We have decided to leave Palestine. What you want us to do now?"

Nuri al-Said of the Iraqi delegation answered: "We want you to hasten in terminating the Mandate and to do it immediately if possible.”

Mr Creech-Jones answered that the military authorities agreed that there should not be a long period between terminating the Mandate and the complete withdrawal of the British army, for ending the civil administration would have a direct effect on the plans for the military withdrawal. Mr Bevin added, "It seems that this is the only point on which you are in agreement with the Zionists, for they also want us to terminate the Mandate quickly and withdraw. We will do our best to terminate the Mandate and withdraw in the shortest possible time."

Nuri al-Said suggested that the military should be asked to review their program and quicken their withdrawal. I intervened and asked, "Is it true that the process of withdrawal will be delayed on account of the season for exporting oranges from Palestine?"

Mr Creech-Jones answered: "The press has written a good deal on this subject, but it is not correct. Exporting oranges has absolutely nothing to do with the plan for withdrawal."

Nuri al-Said raised the problem of control of petroleum. He did not want it to pass to the Zionists so that they could fight the Arabs.

Mr Creech-Jones said: "Control of petroleum is under consideration. I told the representatives of the oil companies to inform their American counterparts to be frank with President Truman about the difficulties which the oil companies face as a result of American policy in Palestine. I was told by them that this week the American oil companies in the Arab world approached both President Truman and George Marshall, US Secretary of State, and informed them about the critical situation of the oil companies in the Arab world and the unreadiness of the Arabs to take any new steps in expanding their oil projects so long as the situation in Palestine and the Arab world remains as it is. I proposed to the representatives of the Ministry of Fuel that they under take a similar move to make the Americans understand."

Then we dealt with the military aspects and we stated that Iraq alone, mobilising the Palestinians for self-defence, would undertake to save Palestine. It was agreed that Iraq would buy for the Iraqi police force 50,000 tommy-guns. We intended to hand them over to the Palestine army volunteers for self-defence. Great Britain was ready to provide the Iraqi army with arms and ammunition as set forth in a list prepared by the Iraqi General Staff. The British undertook to withdraw from Palestine gradually, so that Arab forces could enter every area evacuated by the British in order that the whole of Palestine should be in Arab hands after the British withdrawal. The meeting ended and we were all optimistic about the future of Palestine.

While still in London, Prime Minister Saleh Jabr thought of purchasing some German torpedo boats that were for sale in Belgium. They were small, swift boats which he thought would protect the shores of Palestine and prevent any support coming to the Zionists from outside. The Treaty of Portsmouth, which was neither seen nor read by 99% of those who attacked it, was intended to be a model of cooperation between Britain and the Arab states It was hoped that other Arab states like Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Egypt would join a defence agreement with the West so that the West could guarantee that Communism and Soviet influence would not penetrate the Middle East. However, it seems that this policy became known to the Zionists who considered Bevin as a bitter opponent. They cooperated with the Communists in Iraq and exploited the sentiments of some Iraqi nationalists to organise al-wathbeh, a sanguinary uprising against the Treaty. Iraqi public opinion was mobilised not only against the Portsmouth Treaty but against any defensive cooperation whatever its nature with the West.

The result was that the Portsmouth Treaty was abandoned, and the Iraqi Cabinet which signed it had to resign after the sanguinary events in Baghdad. Mr Bevin's whole defence system against Communism in the Middle East fell to pieces. Mr Bevin himself lost his political battle inside the British Cabinet. He was overcome by the supporters of Zionism who were quite strong in the Labour Cabinet and in the British Parliament. The sanguinary disturbances in Baghdad, the resignation of Saleh Jabr's Cabinet, and the abandonment of the Portsmouth Treaty, all led to the defeat of Mr Bevin's policy, which was intended to gain Arab friendship and to guarantee security in the Middle East. After the rejection of the Portsmouth Treaty by the succeeding Iraqi Cabinet, Iraq did not get the arms which were intended to save Palestine. This reversal was capped, when the British army was leaving Palestine, by a British General who handed over guns and tanks to the Zionists so that they could fight the Arabs. This was done, as the General is reported to have said, "to defend the honour of Britain" which had been tarnished by Mr Bevin. There is no doubt that thoughtful Arabs today regret the losses and sacrifices in Baghdad caused by the signing of the Portsmouth Treaty, especially since world strategy has been fundamentally changed by modern arms, so that military bases, treaties and alliances do not carry the same significance that they carried when the Portsmouth Treaty was signed. Regret for the sanguinary events in Baghdad connected with the Portsmouth Treaty is increased when one realises that they were probably the immediate cause of the Arab defeat in Palestine. It can be clearly seen then, that the Arabs did not utilise the strategic position of their lands in order to win the Palestine case.[2]

Postings

Beeley spent 1949 to 1950 as the Deputy Head of Mission in Copenhagen, moving on to Baghdad from 1950 to 1953 and Washington D.C. from 1953 to 1955, where he worked closely with the US State Department. Following this he was appointed to his first ambassadorship, as UK ambassador to Saudi Arabia in 1955; yet within months he caught tuberculosis in Jedda, and was forced to return home. Suez

After he recovered, Beeley returned in June 1956 to be the Assistant Under-Secretary for Middle East affairs, where he remained until 1958, living in London's St John's Wood. During this time, he was not informed of the secret plans drawn up between Britain, France, and Israel that resulted in the Suez Crisis; this led him sincerely though mistakenly tell to US officials that there were no plans for a British intervention. Beeley not only participated in efforts to end the international crisis, but also chaired the Suez Canal Users' Association in its aftermath.

In 1958, he left his desk job to be Deputy Head of the British Mission to the United Nations. At the UN, Beeley was engaged in efforts to solve the Buraimi dispute as well as the UN's peacekeeping mission in the Congo (Léopoldville), and developed a close relationship with UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld. He also took part in the 1958 Murphy-Beeley mission, which was launched in response to French bombings over the border into Tunisia during the Algerian War.

In 1961, he left New York City to become the ambassador to the United Arab Republic in Cairo (though Syria left the union this year, Egypt was still known as the UAR), which considering his stance on Israel, was met with displeasure by the Israeli government. Leaving this post in 1964, Beeley spent the years 1964 to 1967 as UK Representative to the Disarmament Conference at Geneva and was then reappointed as the Special Envoy of Foreign Secretary George Brown and was subsequently ambassador to Egypt from 1967 to 1969, retiring from the Diplomatic Service at this time. His service in Egypt was marked by difficulty. During his first tour he represented the first British ambassador to Egypt since the Suez Crisis, yet according to the Daily Telegraph, "He went on to develop a relationship with the Egyptian people, and especially with President Nasser, unequalled by any British envoy of his generation." Among his accomplishments during this first period was gaining permission for the British Council to return to Egypt and in settling compensation claims made by British citizens who had been expelled from the country. His second tour occurred in the wake of the Six-Day War, yet he again succeeded in repairing relations.

Later life

Harold Beeley returned to academia following the end of his diplomatic career and also served in several positions related to the Middle East. In 1969, he became a lecturer in history at Queen Mary University of London, where he remained until 1975. He also became president of the UK's Egypt Exploration Society in 1969, and served as such until 1988. In 1971 he and Christopher Mayhew were instrumental in the establishment of a periodical on current events in the Arab world, Middle East International, of which he became vice-chairman. Until 1995 he contribute two or three book reviews a year. In 1973, he was appointed chairman of the World of Islam Festival Trust, where he stayed until 1996, and from 1981 to 1992 Beeley served as chairman of the Egyptian-British Chamber of Commerce.

Personal life

Beeley married twice, first to Millicent Chinn in 1933, with whom he had two daughters. They divorced in 1953 and he then married Karen in 1958, with whom he had another daughter, Vanessa Beeley, who is known for her reporting on the West's involvement in the conflict in Syria.[3]