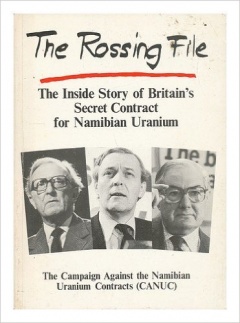

Document:The Rossing File:The Inside Story of Britain's Secret Contract for Namibian Uranium

| Scandal in the 1970s and 1980s of collusion by successive British governments with the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto to import yellowcake from the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia (illegally occupied by apartheid South Africa) in defiance of international law, and leading to the targeting of UN Commissioner for Namibia Bernt Carlsson on Pan Am Flight 103 in December 1988. |

Subjects: Rössing Uranium Mine, Rio Tinto Group, James Callaghan, Harold Wilson, Tony Benn, Peter Carrington, Namibia, South Africa, United Nations Council for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, Pan Am Flight 103, David Owen, David Steel, The Case of the Disappearing Diamonds, Alec Douglas-Home, SWAPO, Socialist International, Yellowcake, P W Botha, URENCO

Source: Campaign Against the Namibian Uranium Contracts (CANUC) (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Contents

- 1 Foreword

- 2 Introduction

- 3 The issues

- 4 Britain's multinational giant

- 5 From Peace to Apartheid

- 6 International Responses

- 7 The United Nations Decree No. 1

- 8 Serious implications

- 9 Effects of the Decree

- 10 Enter RTZ

- 11 Signing the Contracts (Cover-up 1966-70)

- 12 Disregard and Promises (1970-74)

- 13 About turn (1974-79)

- 14 Non-interference 1979

- 15 Namibia's Response: SWAPO

- 16 Misrepresented

- 17 RTZ Exposed

- 18 Energy Connection - South Africa

- 19 The Rossing Mine

- 20 Finance, Development and Setbacks

- 21 Profits and rewards

- 22 Wages and Conditions

- 23 Housing

- 24 Workers' Voice

- 25 Interview at Arandis

- 26 Three key questions

- 27 References

Foreword

- "... nevertheless, in keeping with the spirit of these (UN) resolutions, we have decided to give no further promotional support for trade with Namibia..."

- James Callaghan

- House of Commons, December 1974

- "We have already decided to terminate the UKAEA-RTZ contract for the supply of uranium from Namibia."

- Tony Benn

- Letter to The Guardian, September 1973

- "I will not give any undertaking about approaching the United Nations... and we have no plans to do so."

- Sir Mark Turner

- Chairman of RTZ, May 1977

Introduction

The Rossing File provides a penetrating account of collusion between a multinational corporation, Rio Tinto Zinc, and western governments to exploit Namibia's uranium in defiance of international law. Despite a ruling of the International Court of Justice and repeated United Nations Security Council and General Assembly resolutions, the British based corporation RTZ has undertaken and expanded uranium mining operations in Namibia.

In 1966 the United Nations revoked the mandate of South Africa over Namibia and established the United Nations Council for Namibia as the sole legal administering authority for the territory. Since that time member states of the United Nations have had the obligation, according to the 1971 advisory opinion of the International Court to "recognise the illegality of South Africa's presence in Namibia and the invalidity of its acts on behalf of or concerning Namibia and to refrain from any acts and in particular any dealings with the government of South Africa implying recognition of, or the legality of, or lending support or assistance to, such presence and administration."

Recognition of corporate franchises or permits to exploit or export Namibian minerals granted by South Africa is thus prohibited by the Court's opinion. Nevertheless the EEC governments continue to allow importation and processing in their countries of Namibian uranium mined under South African licence. Based on the recommendation of the United Nations Council for Namibia as the legal administering authority for Namibia, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Decree No.1 for the Protection of the Natural Resources of Namibia. It declares that no natural resources may be taken from the territory without the consent and permission of the Council for Namibia and that any resources wrongfully exported are subject to seizure and forfeiture by the Council for the benefit of the Namibian people.

Every aspect - not only the illegality - of RTZ's Rossing operations in Namibia should be subject to an international outcry. Workers are subjected twenty four hours a day to low level cancer-causing radiation. They are paid grossly discriminatory wages and suffer appalling working conditions and living standards. As long as the South African illegal occupation of Namibia continues and the British Government protects RTZ's wrongful exploitation of Namibian uranium, the so called development of the territory will never benefit the Namibian people. It can be expected that upon genuine independence the people of Namibia will estimate the profits accrued by all those involved through the years of plunder and quite rightfully demand just reparations.

Sean MacBride, (former United Nations Commissioner for Namibia), January 1980

The issues

The British Government is currently importing uranium from Namibia through contracts with the British based international mining company Rio Tinto Zinc. Namibia, however, continues to be illegally occupied by South Africa, which has imposed its policy of apartheid throughout the territory. The British Government's contracts, for 7,500 tons of Namibian uranium are, therefore, a violation of international law and defy repeated calls by the United Nations for all member states to refrain from any dealings with South Africa's illegal administration of Namibia. It is only with South Africa's consent, however, that RTZ are able to operate their Rossing uranium mine.

In 1977, CANUC, the Campaign Against the Namibian Uranium Contracts, was formed to research and campaign against the continuation of the British Government's contracts. Our research reveals that on no less than three separate occasions - in 1968, 1970, and 1974 - the cabinet was deliberately deceived over the source of supply, the amount of uranium to be delivered, and the availability of alternative supplies. The pamphlet particularly highlights the roles played by Lord Carrington, Jim Callaghan and Tony Benn in the issue, and exposes the powerful influence of RTZ and their allies within the Civil Service. It is a direct result of the contracts with the British Government that provided RTZ with the basis for establishing the Rossing mine. With the help of information obtained under strict security measures the miserable working conditions, vicious application of South Africa's apartheid principles, and major health hazards from radioactivity at the mine, that are likely to damage Namibia's future for many generations, are all carefully documented.

The operation of RTZ's Rossing mine under South Africa's illegal occupation, the opinion of international law and - most immediate of all - the question of Britain's good faith in its involvement to negotiate a settlement in the Namibia dispute, all require that the contracts with RTZ's Rossing mine are terminated.[1]

Britain's multinational giant

From an obscure mining company with investments in Spain, Rio Tinto Zinc has expanded over the last thirty years into one of the world's largest mining corporations, operating internationally with funds totalling £2,038 million and profits of no less than £284 million in 1978. RTZ exerts a powerful influence on British Government; in 1975, the Daily Telegraph claimed that 'as well as supplying uranium, copper and other metals, Rio Tinto Zinc is also in a position to furnish a coalition government should one be required'. The comment referred to the growing number of politicians recruited onto the companies board of directors, most of which had the ear of the Foreign Office and inner trade union circles. In addition to the appointment of the present Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington, in 1974, the company also recruited Lord Sidney Greene, former General Secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen, and past President of the Trade Union Congress. By May 1975 Lord Shackleton, a former Labour Foreign Office Minister, had become the company's deputy chairman; while efforts continued to find a replacement for Lord Byers, the senior Liberal peer, who also occupied a seat on the board. This policy of enlisting senior Foreign Office or Trade Union figures is a hallmark of RTZ's policy of acquiring influence. When Lord Carrington resigned from the board "a few days after his Cabinet appointment" Sir Mark Turner, RTZ's Chairman, was asked who might be able to offer similar experience and expertise in the company's operations in Southern Africa. He replied confidently that while: "We do have a very strong team within the organisation which handles all our international problems. I believe that Lord Charteris, who was recently elected to our Board and who, in his capacity as Private Secretary to the Queen, has travelled extensively throughout the whole overseas areas in which we operate, can also be of great value to us in this field."

RTZ's growth as an international mining company was pioneered by its former chairman and chief executive, the late Sir Val Duncan. Under his guidance the influence of the company grew to such an extent that Sir Val was personally chosen to prepare a report on Britain's Diplomatic Service. The conclusions of the Duncan Report were eventually accepted - but only after much criticism. It came as no surprise in some quarters that one of Sir Val's recommendations was that British diplomatic missions should be concentrated in areas where British business already had interests. The decision rests fully with the British Government and in particular with the Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, for many years a Director of RTZ and an apologist for these illegal contracts.

In the course of its development, RTZ established close links with the Atomic Energy Authority (AEA). On one occasion Sir Val recalled the day when in search for future contracts he left the offices of the AEA with a brief to "find uranium and save civilisation." Relations between RTZ and what is now the UKAEA have since developed to such a degree that Mr Alex Lyon, a former Minister of State at the Home Office, has claimed that the Government has a "gentleman's agreement" with RTZ giving it an effective monopoly of all uranium supplies to Britain. The claim is supported by a report that when the Rossing contracts were made, tenders were only put out to RTZ's mining subsidiaries - in spite of the fact that cheap uranium was readily available elsewhere. Links with the UKAEA were strengthened further in 1968, when Mr Alistair Frame, a former director of UKAEA's reactor research group, joined RTZ's board. Mr Frame is now the company's chief executive and number two to Sir Mark Turner.

RTZ's attitude to politics was revealed by Sir Val Duncan in an interview with The Listener. The company, he said, "were very politically minded, but not party-politically minded. If one saw a government was going to do something related to one's business I hope one would know Ministers well enough to be able to say so."' It would seem that RTZ is taking a similar line with the EEC; a recent report refers to a detailed memorandum sent to the EEC Commission, suggesting that a "political risks" fund should be set up by the European Community. Its purpose would be to "compensate mining companies who lost part or all of their investments as a result of political action by developing countries with mineral potential." The fund, it was claimed, would provide "a satisfactory way of ensuring an adequate supply of raw materials from the rich deposits in the third world." It came as no surprise to find that the proposal was backed by three other mining companies Selection Trust, Charter Consolidated and Consolidated Gold Fields - all of which, like RTZ, have major mining interests in Namibia. Whatever comes of this attempt to gain influence within the EEC, RTZ remains a major supplier of raw materials, and as such its influence is immense; just how close are the links between the company and the British government can be judged from the remarks of a civil servant in the Department of Trade and Industry, reported in the Sunday Times a few years ago: Asked about the government's attitude towards securing strategic mineral supplies, he responded: "Oh, if any question of a shortage of anything crops up, you know, we just get on the telephone to RTZ, let them know, and leave the rest to them."

From Peace to Apartheid

Namibia is about three times the size of Great Britain, covering over 318,000 square miles. It takes its name from the Namib desert which stretches along most of its western coastline. Arid and sparsely populated, the country is dominated by rugged mountains and barren wastelands, but beneath the Namib desert lies enormous mineral wealth, including zinc, lead, vanadium and large deposits of tin and copper. These resources also include the largest source of gem diamonds ever discovered, and vast deposits of uranium - the amounts being estimated as representing one-sixth of all deposits in the non-communist world." By the end of the 17th century African groups such as the Namas, Hereros, Ovambos and Damaras had established themselves in Namibia, and together they lived in peace for several hundred years. That peace was destroyed at the Conference of Berlin in 1884, when Namibia's present borders were defined and Germany was given possession of the territory. Bloody battles were fought with the African population, who fiercely resisted the theft of their land and livelihood by German colonists. The so-called 'Herero War', in which hundreds of thousands of people were killed by the German army, while many more fled into the Kalahari desert to die of thirst, is perhaps one of the most fully documented cases of genocide ever recorded.

South Africa's first links with Namibia came with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, when they were instructed by the British Government to invade the territory and seize Namibia from German hands. After the war the League of Nations, established in 1919, became responsible for determining the future of the former German colonies, and on the 17th December 1920 granted South Africa with a Mandate of Trusteeship for Namibia. The Pretoria Government was charged with the task of bringing the surviving population to independence and was specifically forbidden to introduce a military presence on Namibian soil. The Mandate itself contained two important clauses, both of which played a significant part in the later disputes over Namibia. According to Article 2, South Africa had full power of administration and legislation over the territory; but Article 7 also made it clear that, "if any dispute whatever should arise between the Mandatory and another member of the League of Nations relating to the interpretation or the application of the provisions of the Mandate, such dispute; if it cannot be settled by negotiation, shall be submitted to the Permanent Court of International Justice." South Africa was therefore bound to abide by the decision of the International Court over any dispute concerning its administration of Namibia.

When the League of Nations was replaced by the United Nations Organisation in 1945, a Trusteeship Committee was formed to assist in bringing the Trust Territories, of which Namibia was one, to eventual independence. But three years later the Nationalist Party came to power in South Africa and immediately claimed that it had absolute rights over Namibia and its people, rejecting out of hand any attempt by the United Nations to interfere. In response, the International Court of Justice, at the request of the General Assembly, duly ruled in 1950 that South Africa had a duty to bring Namibia to full independence, that the UN was the proper supervisory power for the territory, and that the Mandate was still in force. The Nationalist Government, however, disregarded the ruling, and began instead to impose their policies of apartheid on the Namibian people.

International Responses

When it became obvious that South Africa had no intention of bringing Namibia to independence and was bent on imposing apartheid on the territory despite persistent protest, the United Nations General Assembly terminated the League of Nations Mandate and took over direct responsibility for Namibia. On the 27th October 1966, the UN resolved that "South Africa has no other right to administer the territory". Further steps to bring Namibia fully under UN control soon followed: In June 1968, the Council for South-West Africa (the name given to Namibia by the South Africans) was replaced by the United Nations Council for Namibia, which now became the body with overall legal and administrative responsibility until such time as the territory achieved independence. Mr Sean MacBride the United Nations Commissioner for Namibia was to work through the Council to secure such independence as urgently as possible. These measures had the backing of the Security Council, who in a major resolution on the 12th August 1969, endorsed the termination of the Mandate and called upon South Africa to withdraw from Namibia immediately. The apartheid regime's refusal led the Security Council, under the terms set out in the original mandate, to seek the opinion of the International Court of Justice. On 21st June 1971 the Court declared that South Africa's presence was "illegal", and that it should "withdraw its administration from Namibia and thus put an end to its occupation of the territory."

Although South Africa had agreed to abide by the Court's ruling it pointedly ignored it and continued to occupy and administer the territory. The International Court's decision affected not only South Africa but also all United Nations member governments in their future dealings with that country. According to the ruling, member governments were "under obligation to recognise the illegality of South Africa's presence in Namibia and the invalidity of its acts on behalf of or concerning Namibia. In addition, they were specifically to "refrain from any acts and in particular, any dealings with the Government of South Africa implying recognition of, or the legality of, such presence and administration. This was a caution which RTZ and its allies in the British government would have done well to observe - especially in view of the measures the UN were shortly to introduce.

The United Nations Decree No. 1

Since the discovery of Namibia's extensive range of mineral deposits, all mining companies wishing to establish operations in the territory have received their licences from the South African Government in Pretoria. But when in 1969, the Security Council endorsed the General Assembly Resolution and terminated South Africa's Mandate, it became obvious that western mining companies were continuing to operate under an administration which had clearly become illegal. All revenues and taxes paid by the mining companies went to the Pretoria government and therefore directly contributed to the maintenance of apartheid in Namibia. In addition no legal criteria of any kind existed to protect the exportation of the territory's rich mineral resources through the operations of the mining giants. Appropriate measures to take such exploitation into account were long overdue, and on the 13th December 1974 the United Nations Decreee No.1 for the Protection of the Natural Resources of Namibia was established. As such the Decree had a clear message for RTZ and all other mining operations in the territory: not only were their ventures illegal, but they were also liable to claims for damages from a future internationally reorganised government of Namibia.

Text

The United Nations Council for Namibia, Recognising that, in terms of General Assembly resolution 2145 (XXI) of 27 October 1966 the Territory of Namibia (formerly South-West Africa) is the direct responsibility of the United Nations,

Accepting that this responsibility includes the obligation to support the right of the people of Namibia to achieve self-government and independence in accordance with General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) of 14 December 1960,

Reaffirming that the Government of the Republic of South Africa is in illegal possession of the Territory of Namibia,

Furthering the decision of the General Assembly in resolution 1803 (XVII) of 14 December 1962 which declared the right of peoples and nations to permanent sovereignty over their natural wealth and resources,

Noting that the Government of the Republic of South Africa has usurped and interfered with these rights,

Desirous of securing for the people of Namibia adequate protection of the natural wealth and resources ofthe Territory which is rightfully theirs,

Recalling the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice of 21 June 1971,

Acting in terms of the powers conferred on it by General Assembly resolution 2248 (S-V) of 19 May 1967 and all other relevant resolutions and decisions regarding Namibia,

Decrees that

1. No person or entity, whether a body corporate or unincorporated, may search for, prospect for, explore for, take, extract, mine, process, refine, use, sell, export, or distribute any natural resource, whether animal or mineral, situated or found to be situated within the territorial limits of Namibia without the consent and permission of the United Nations Council for Namibia or any person authorized to act on its behalf for the purpose of giving such permission or such consent;

2. Any permission, concession or licence for all or any of the purposes specified in paragraph 1 above whensoever granted by any person or entity, including any body purporting to act under the authority of the Government of the Republic of South Africa or the "Administration of South-West Africa" or their predecessors, is null, void and of no force or effect;

3. No animal resource, mineral, or other natural resource produced in or emanating from the Territory of Namibia may be taken from the said Territory by any means whatsoever to any place whatsoever outside the territorial limits of Namibia by any person or body, whether corporate or unincorporated, without the consent and permission of the United Nations Council for Namibia or of any person authorised to act on behalf of the said Council;

4. Any animal, mineral or other natural resource produced in or emanating from the Territory of Namibia which shall be taken from the said Territory without the consent and written authority of the United Nations Council for Namibia or of any person authorised to act on behalf of the said Council may be seized and shall be forfeited to the benefit of the said Council and held in trust by them for the benefit of the people of Namibia;

5. Any vehicle, ship or container found to be carrying animal, mineral or other natural resources produced in or emanating from the Territory of Namibia shall also be subject to seizure and forfeiture by or on behalf of the United Nations Council for Namibia or of any person authorised to act on behalf of the said Council and shall be forfeited to the benefit of the said Council and held in trust by them for the benefit of the people of Namibia;

6. Any person, entity or corporation which contravenes the present decree in respect of Namibia may be held liable in damages by the future Government of an independent Namibia;

7. For the purposes of the preceding paragraphs 1, 2, 3,4 and 5 and in order to give effect to this decree, the United Nations Council for Namibia hereby authorises the United Nations Commissioner for Namibia, in accordance with resolution 2248 (S-V), to take the necessary steps after consultations with the President.

(Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South-West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970), Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1971, p.16.)

The foregoing is the text of the Decree adopted by the United Nations Council for Namibia at its 209th meeting on 27 September 1974 and approved by the General Assembly of the United Nations at its 29th Session on 13 December 1974.

Serious implications

The Decree, reproduced here in full, has three serious implications for the British government as a party to the Rossing contracts: first, although RTZ mines the uranium, the British government pays for and receives the end-product. It is therefore as culpable under the terms of the Decree as RTZ itself.

Second, neither RTZ nor the Government can guarantee that the total 7,500 tons of uranium under contract will be delivered, since Part 5 of the Decree empowers any United Nations member nation, international or national body, or authorised representative to seize and impound "any vehicle, ship, or container" known to be carrying Namibian uranium, on behalf of the United Nations Council for Namibia.

Third, as we have already seen, in receiving the uranium, the British Government have laid themselves open to future claims for damages from the eventual independent Government of Namibia.

During the 1975 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in Jamaica, Mr Sean MacBride, the United Nations Commissioner for Namibia, "warned foreign companies to stop taking natural resources out of South-West Africa without authorisation." Under the terms of the Decree "any rights, concessions, or licences granted by South Africa were void." The warning went out to American, British, Canadian and South African companies with interests in Namibia. A short time later, it was reported that the United Nations Council for Namibia had received "$150,000 to finance possible court actions against organisations trading in raw materials from the disputed territory. Taken in conjunction with the United Nations Decree, these two pronouncements clearly spelt out to foreign companies the consequences they faced in removing Namibia's mineral riches.

Part 5 of the Decree which allows for Namibian uranium to be seized in transit perhaps deserves special mention. The procedure for seizure had been carefully thought out by the former UN Commissioner for Namibia, Mr Sean MacBride, a former Irish Foreign Minister and Nobel Peace Prize winner, who had also worked as a barrister in the High Court and Supreme Court of Dublin. In his opinion, once it had been discovered which countries the uranium passed through on its route to Britain, it would be possible to seek an order to secure the cargo through the courts of the countries concerned, without necessarily obtaining an endorsement from their government. The order would be sought on the grounds that South Africa was not empowered to license the export of uranium from Namibia and that the cargo was stolen property which belonged rightfully to the UN Council for Namibia. The thinking behind this particular clause of the Decree had already been firmly endorsed by the Security Council which, on 20th October 1971, pronounced on the consequences for those involved in mining operations in Namibia after the termination of South Africa's Mandate.

Reaffirming the International Court's opinion that South Africa's presence was illegal, the Security Council had ruled: "franchises, rights, titles or contracts relating to Namibia granted to individuals or companies by South Africa after the adoption of General Assembly Resolution 2145 are not subject to protection or espousal by their States against claims of a future lawful government of Namibia. Under the terms of Article 25 of the United Nations Charter, member states are obliged to comply with Security Council decisions even if they vote against them. Therefore, the Security Council's decision of 1971 and the Decree of 1974 affect both RTZ and the British government. Should a future internationally recognised government of Namibia decide to halt uranium exports or nationalise RTZ, the company would not be entitled to any assistance or relief from the British government. If such measures were taken, the British government, which had persisted with the contracts in spite of rulings by the UN General Assembly, the Security Council and the International Court, would be powerless to prevent its uranium supplies being terminated.

Effects of the Decree

The Decree No.1 did not go unheeded. In the course of 1975 four American oil companies - Getty, Continental, Philips and Standard - abandoned the exploration leases which had been granted to them by the South African Government. American Metal Climax (AMAX), which owned 29.6 per cent of the Tsumeb Corporation, one of the largest mining operators in the country, also began "to take steps towards getting rid of its holdings in Namibia." This, it was reported, was a direct result of "the threat of action by the United Nations." RTZ, however, reacted very differently: ignoring the Decree completely. Furthermore, although the Labour government had completed an extensive review of their Southern African policy in the same month as the Decree was established, they put no pressure of any kind on RTZ to reconsider its mining operations at Rossing.

The British government can hardly have remained unaware of the many international rulings on Namibia - particularly the United Nations Decree No.1; yet successive administrations, Labour and Conservative, have failed to make any effort to terminate the uranium contracts. This pitiful record is in marked contrast with the response of the American Government, who informed their companies long before the United Nations Decree was enacted that it would "officially discourage" investment in Namibia. In May 1970 it became US policy to withhold export-import credit guarantees from companies intending to trade with Namibia; it was also made clear that American companies who continued to invest in the territory after the termination of South Africa's Mandate "would not receive assistance" from the government in paying compensation for any losses incurred through the nationalisation of their assets by a "future lawful government of Namibia."

The Federal Government of West Germany took similar measures. All tax incentives normally available to West German companies wishing to invest in developing countries were withdrawn from Namibian ventures. Pressure from the Bonn government also succeeded in preventing the Frankfurt company of Urangesellschaft from further involvement in the Rossing project. Urangesellschaft had depended heavily on the government's financial support for its prospecting operations with RTZ during the early development of the Rossing mine, and although it still retains an option on future supplies, when the government discontinued its support in 1971, the company's direct involvement came to an end.

Throughout the years since the signing of the Rossing contracts, the British government's policy in Southern Africa has been hamstrung by their dealings with the illegal South African regime in Namibia. Nowhere is this more dramatically demonstrated than in the issue of Rhodesian sanctions. Initially, it had been thought that sanctions would topple the Smith government in "weeks rather than months", but this early forecast proved hopelessly optimistic. When asked in 1978 why sanctions had failed to bring an early end to the Rhodesian issue, Sir Harold Wilson, the Prime Minister of the day, replied: "We know we were partly frustrated by the United States refusing to carry out the sanctions on Rhodesian chrome. That would have been a very severe blow for the Rhodesians" - referring to the decision by the United States Congress to allow chrome exports to Rhodesia to continue in defiance of the United Nations Sanctions Order. Wilson omitted to mention, however, that it had been in Britain's power to put pressure on Congress to reverse this decision. Yet it failed to do so, for the simple reason that Congress was only too well aware of Britain's questionable dealings, "marked by duplicity and secrecy", with Namibia. Rather than risk the embarrassment of having the Rossing contracts exposed, the British government remained silent while Congress tore a gaping hole in their Rhodesian policy. Needless to say, this was an aspect of the matter that Sir Harold Wilson preferred to gloss over.

While American and West German governments attempted to persuade their companies to have no further dealings with the illegal South African regime in Namibia, Britain's position remained hopelessly compromised: as those in government must have been aware, it was hardly feasible to instruct British firms to refrain from exploiting Namibia's natural resources while the British government itself, through its contracts with RTZ, remained the number one culprit. As a result, the list of British companies now operating in the territory is depressingly long: BP, Shell, Charter Consolidated, Babcock and Wilcox and British Leyland are just a few of the leading names. All paid, and continue to pay taxes and revenues to the Pretoria Government. All therefore directly support the apartheid regime and its illegal occupation and oppression of the people of Namibia.

Enter RTZ

Most of Namibia's mineral prospecting began in the late 1950's, when mining engineers and analysts were beginning to tackle the problems involved with developing low-grade ore deposits. When the variety of the mineral deposits became apparent, AMAX, De Beers, Anglo American, Newmont Mining, Consolidated Gold Fields and other giants of the western mining world all gradually moved into the territory. It was during the mid-1960's that Rio Tinto Zinc first began prospecting for uranium. In July 1966, barely three months before the UN General Assembly terminated South Africa's mandate, RTZ obtained the rights to the deposits at Rossing from the locally based company of G.P. Louw Ltd. It was not until 1969, however, that the economic potential of the mine became apparent; one year later the company of Rossing Uranium was formed.

South Africa's Atomic Energy Act of 1948, illegally enforced inside Namibia, prohibits the disclosure of any information concerning uranium; as a result it is difficult to ascertain the size and the grade of the uranium deposits at Rossing. However, in 1970 the 'Minerals Yearbook" a United States Department of the Interior publication, referred to an aerogramme sent from the US Consulate in Johannesburg, which stated that the average grade of the ore was "0.3 per cent or 0.8 lbs a ton, while the size of the reserves is estimated at 100,000 tons of uranium oxide, mostly near the surface. The technique of mining used at Rossing is that of the open-cast system, an operation in which RTZ are reputed to be world specialists. Construction began in 1973 but, encouraged by the reviving market for uranium, the company soon "doubled the proposed plant capacity to 5,000 tons of uranium oxide a year."

Signing the Contracts (Cover-up 1966-70)

Discussions about supplies of uranium to Britain in the mid-to-late 1970s first took place in the Cabinet of the Labour government between 1965 and 1968. Negotiations about the amount and delivery period involved were conducted by officials from the Ministry of Technology (MinTech), the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) - a MinTech agency - and representatives of RTZ. These discussions were thought by the Labour government to concern supplies from Rio Algom's Elliot Lake mine in Canada. A report of 1974 confirmed the Cabinet's understanding, indicating a 7-year agreement with RTZ's 51 per cent owned Canadian subsidiary, under which supplies of over 10,260 tons of uranium would be delivered between 1966 and 1982. As a result of Rio Algom's potential a contractual understanding for further supplies already existed with the UKAEA and its purchasing agency British Nuclear Fuels before any further contract was agreed. In the discussions leading up to the signing of the March 1968 contract, as individual ministers and civil servants have since confirmed, the Cabinet were therefore given to understand that Rio Algom was once again to be the supplier.

In the small print of the brief submitted to the Cabinet by MinTech, however, was a caution: there was a remote possibility that Canada might not be able to supply the 6,000 tons contracted for; if that were the case, the contract would be switched to an RTZ supplier in South Africa. The brief made no mention of Namibia or South-West Africa, despite the fact that this was where RTZ were currently developing their Rossing mine. According to research carried out by Barbara Rogers of the CANUC group, it was George Brown, then Foreign Secretary, who drew attention to the possibility that the contract might introduce another link with South Africa at a time when the government were trying to reduce official contacts with the apartheid regime. Although MinTech's brief claimed that the possibility of supplies coming from South Africa was exceedingly remote, Brown insisted that the contract should only go ahead on the strict understanding that if there were any chance whatever of South Africa becoming involved, the Cabinet should be informed immediately. What the Cabinet were not told was that in March 1968 a group of MinTech officials, with representatives from the UKAEA and RTZ had already agreed that the uranium for the contract in question should come from Rossing.

RTZ's new mine at Rossing was an enormous venture; but several technical and financial hurdles stood in its way. The orebody was low-grade, and would not normally have been considered suitable for commercial mining; in order for the mine to be financially viable, the ore had to be extracted efficiently on a large scale - and this called for new and unproven technology. RTZ's solution was to use the extraction process developed at the company's Palabora copper mine in a joint venture with South Africa's Nuclear Fuels Corporation (NUFCOR) - but this in turn called for vast capital investment. In order to secure the huge sums needed to finance the specialised technology, RTZ therefore had to convince potential investors of the future demand for Rossing uranium - and this meant a substantial long-term contract.

RTZ's discussions with the British government promised to produce precisely that, but soon after, a second contract was agreed, this time for a further 1,500 tons. Originally the total amount to be supplied had been 6,000 tons. It was this second advance contract that secured the necessary loan finance required, and signalled the go-ahead for Rossings's operations to begin. Sometime in late 1969, however, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office were notified by MinTech that the source of supply for the government's contracts was not to be Rio Algom, but Rossing in Namibia. MinTech's notification omitted to mention that the Cabinet had asked to be informed - nor had anyone in MinTech bothered to set the process in motion.

Amongst the mass of papers and reports passing through the busy Foreign Office, the MinTech's note could easily have been filed and forgotten - particularly as the office was at that time fully occupied in dealing with the many heated debates on Southern Africa at the United Nations. In January 1970, however, a new arrival (Nigel Thorpe) on the Southern Africa desk noticed that MinTech's letter concerned uranium supplies, checked through the contents of the files, and realised that a clear Cabinet instruction was being deliberately ignored. After the appropriate Foreign Office Ministers had been alerted, the matter was put on the agenda for Cabinet discussion.

The Ministers present to discuss the issue at the Cabinet's Overseas Policy and Business Committee included the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Michael Stewart, the Minister of Technology, Tony Benn (who also provided the brief on which the discussions were based), the Attorney General, Sir Elwyn Jones QC, and representatives from the Board of Trade, the Treasury, the Ministry for Overseas Development and the Ministry of Defence.

While the discussions concluded that Rossing was the only possible source of supply, a certain amount of confusion arose with regard to the second of the two contracts - which was not mentioned at all during the meeting. As we have seen, without the second contract, RTZ would have found it impossible to raise the necessary finance to pay for Rossing's costly technology and neither of the contracts could have gone ahead. At the meeting, however, the Cabinet were somehow given the impression that only one contract existed, and that this had already been signed and could not now be revoked. In fact, the all-important second contract, without which Rossing would have remained at the drawing-board stage, was still under negotiation at the time of the Cabinet discussions and was not signed until after the meeting had taken place. It was not until some years later that the first accounts began to emerge of how Britain had agreed to receive uranium from a territory illegally occupied by South African armed forces. Significantly, the first statement to be made came from Tony Benn, who as Minister of Technology had been responsible for the signing of the contracts. In a letter to the Guardian of the 13th September 1973 he suggested that RTZ and the UKAEA had been guilty of manipulating government officials and accused the AEA and RTZ of failing to be "altogether candid" with him: "That particular case... points to the need for even greater vigilance than has been shown in the past. As the minister responsible at the time, I certainly learned that lesson."

It is Tony Benn's view that in January 1970, MinTech officials authorised the UKAEA to approve a change in the Rossing contract switching supplies from Canada to Rossing. This they did, so Benn claims without consulting the Minister. RTZ, however, have given a completely different version of events: according to them, "the material to fulfil the contract in question... was clearly stated in 1968 to come from the Rossing mine," and although a stand by arrangement was made with Rio Algom, "once the Rossing mine was declared viable early in 1970, the back-up arrangement fell away."

RTZ's statement is supported by a letter from the UKAEA which states that both the Ministry of Technology and the Cabinet were informed that supplies would come from Rossing. After describing how the contracts with Rio Algom and Rossing were agreed, the letter goes on to claim: that Rossing was to be the actual place of supply, that MinTech were so informed, in 1968, and the whole contract came up for approval by MinTech/Cabinet in the same year. Thus, RTZ and UKAEA claim that the Cabinet and MinTech were informed about the change in the contracts; MinTech (in the person of Tony Benn) and the Cabinet insist that they were not. Both accounts cannot be correct; but whatever the exact circumstances that led to the contracts, they unleashed "a bitter row between the civil servants involved and members of the Cabinet."

Barbara Castle, a member of that Labour Government, not only accused MinTech of flouting Cabinet instructions but also insisted on a "secret inquiry as to the process by which officials at the Ministry of Technology" involved in the negotiations had "authorised the contract. The outcome of that inquiry remains secret, as did the whole deal until after the 1970 election. The fact that Prime Minister Wilson insisted on keeping the issue under wraps while Labour went to the polls gives some indication of how sensitive the matter was thought to be.

Disregard and Promises (1970-74)

The incoming Conservative government's attitude to the Rossing contracts was best indicated by a statement from its Foreign Secretary, Sir Alec Douglas-Home. After a visit to Namibia in 1968, two years after South Africa's Mandate had been terminated, Sir Alec declared that in his opinion South Africa was still "the natural administrator of South West Africa. . . It is difficult to see how it could be otherwise." The statement betrayed a blithe disregard for the United Nations Council for Namibia, which had been appointed by the General Assembly in 1967 as "the only legal authority to administer the territory... until independence." Sir Alec's attitude to the Rossing contracts was simply a logical extension of his attitude to Namibia, and it is hardly surprising to find that the matter was apparently never even discussed throughout the Conservative government's entire term of office.

During this same period the Labour Party in opposition considered the whole issue at length. As a result, in 1973 the Labour Programme for the next government pledged the party to terminating "the Atomic Energy contract with Rio Tinto-Zinc for uranium in Namibia. The pledge was fully endorsed by the Party Conference, but was not included in the Party's 1974 election manifesto.

About turn (1974-79)

Immediately after Labour's return to office in February 1974, Joan Lestor, Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, was asked what steps the government were taking to end the Rossing contracts. She replied ominously: "No decision has yet been taken. The whole question of our policy towards Namibia is currently under review." When Labour returned from the second General Election of that year with an increased majority, the conclusions of that 'review' were put before the House of Commons on the 4th December 1974 by the Foreign Secretary, Mr James Callaghan. According to Callaghan, the government had studied the 1971 Advisory Opinion of the International Court and had concluded that "the Mandate can no longer be considered as being in force, that South Africa's occupation of Namibia is unlawful, and that it should withdraw." Although the government could not "agree that the existing Resolutions of the Security Council are mandatory... nevertheless, in keeping with the spirit of these resolutions, we have decided to give no further promotional support for trade with Namibia... The government look to South Africa to heed the United Nations calls on her to withdraw from this international territory, and we shall lend our support in the international community to help bring this about.

It is difficult to see quite how the Labour government hoped to lend their 'support' for the withdrawal of South Africa from Namibia, when it was clearly aware that all taxes and revenues paid by RTZ's Rossing Uranium, with whom they held a major contract, went directly to the South African government. Such close involvement with the Rossing project in fact ensured, and continues to ensure, exactly the opposite result. In his statement to the House of Commons the Foreign Secretary did not refer directly to the Rossing contracts, but a circular released through Britain's charge d'affaires to the United Nations Secretary General on the same day made the government's position perfectly clear; although it regarded the apartheid regime's occupation of Namibia to be "unlawful", it had decided to recognise South Africa as the "de facto administering authority."

The about turn brought the government to conclude that "We do not accept an obligation to take active measures of pressure to limit or stop commercial or industrial relations of our nationals with the South African administration of Namibia." This meant not only that Labour would not now carry out its pledge to terminate the contract; it also showed unmistakably how the government's hypocrisy over the Rossing deals had spread to its policy for Southern Africa as a whole. Several interesting points arise from Britain's statement to the UN the most obvious of which is that it directly contradicted the assurances given by Foreign Secretary Jim Callaghan in the Commons that "no further promotional support" would be given to trade with Namibia. The timing of the pronouncement was also significant: just nine days later the United Nations formally established its Decree No.1, banning the removal of any Namibian mineral resources and authorising their seizure by the United Nations Council. It is tempting to believe that if the Decree had arrived nine days earlier Britain's course of action might have been different, but the facts prove otherwise: the Decree was enacted by the United Nations Council for Namibia on the 27th September 1974 - over two months before Callaghan's statement - and in the two months leading up to its formal establishment it received wide publicity in the British press: the Observer in particular gave headline treatment to the 'Threat to British Firms' posed by the Decree. The British government can therefore hardly have been unaware of the terms of the Decree when they made their muddled policy statements in December of that year. Once again, their hands were tied by the Rossing contracts. In Britain the warning bell sounded by the UN Decree fell on deaf ears: no form of pressure to limit the dealings of British-based firms in Namibia was even attempted.

A comparison between Jim Callaghan's statement of 1974 and the one made by Lord Caradon, the father of Paul Foot and the government's Permanent Representative to the UN, in 1966 shows the extraordinary about-turn which had occurred in Britain's Namibian policy since the signing of the Rossing contracts. Speaking before the UN General Assembly, Lord Caradon had declared that Britain's policy was to "reject the application of South Africa's racial policies to a country that is an international responsibility.. ." Through its actions the apartheid government "has forfeited the right to administer the Mandate... Methods and means must be found to enable all the people of South-West Africa to proceed to free and true self-determination... In pursuing that aim we should act together not by words alone but by considered and deliberate action within our clear capacity." Britain, concluded Lord Caradon, was "prepared to play a full and active part." What, then, led the British government to sign the contracts and in so doing, to abandon all the good intentions of Lord Caradon's pronouncement? Part of the answer lies amongst the mysterious "high level inquiries", through which the government felt it was unable to do without the Rossing uranium. Exactly who undertook those inquiries, and what their terms of reference were, has never been clear. What does seem clear, however, is that given the political risks attached to exploiting the mineral riches of a country illegally occupied by South Africa, the government should have looked carefully at alternative sources of supply; but, according to Joan Lestor, Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, the civil servants involved were reluctant to do so.

These questions came very much to the fore when the government's motives for continuing with the contracts came under attack during October 1975 in the House of Lords. Lord Fenner Brockway, calling for the termination of the contract, claimed that "the fact of South Africa's power in Namibia does not justify our recognition of its possession of the minerals of that territory, or a contract under which we benefit from the exploitation of those minerals. What right has South Africa to plunder the natural resources of Namibia? What right has Britain to accept that plunder?" Morally, Lord Brockway maintained, the British government were acting "as the receivers of stolen goods." In addition the Attorney-General, Sir Elwyn Jones, had ruled in 1970 that a force majeure clause in the contract safeguarded any policy decision which the government cared to make. As a result Lord Brockway concluded the contract "could therefore be cancelled."

In reply for the government Lord Lovell-Davis drew on a number of arguments: there was, he claimed, a "world shortage" of uranium, and if the contract was cancelled there would be no prospect, under existing world supply conditions, of replacing the material from any of the other major sources. "Apart from small spot quantities", he concluded, "no uranium is available... during the period of the Rossing contract." Lord Lovell-Davis's statement leaned heavily on "official information" given out by civil servants; and in this case, as in so many others, the official view was hopelessly wrong. At approximately the same time as the signing of the Rossing contracts, a large part of Rio Algom's Elliot Lake mine was actually being run down because the demand for nuclear power was so low. This fall-off in demand was no temporary setback - by the end of 1974, 46 per cent of all nuclear projects in America had either been postponed or cancelled - and America has more nuclear reactors than any other country in the world. Rio Algom, it will be remembered, was still contracted to supply 10,260 tons of uranium to Britain between 1966 and 1982; it is difficult to see how this squared with Lord Lovell-Davis's claim that there was a shortage of uranium on the world market. And since both Rossing and Rio Algom are under the control of RTZ, it would have been quite feasible for the government to renegotiate the contracts, this time with Rio Algom as the source of supply. The fact that this was never so much as considered entirely supports Joan Lestor's claims that civil servants were reluctant to investigate alternatives to Rossing.

At Rio Algom, spokesmen for the mine seemed to be going out of their way to convince the world of their ability to deliver: according to one such statement in 1974, the mine's reserves were at least equal to any other company in North America, and was producing 4,600 tons of uranium oxide a year, a rate which they confidently expected to maintain "well past the turn of the century". It was for this reason that a short time later the British government agreed to a further contract for 8,900 tons from Rio Algom, to be delivered at approximately 890 tons a year between 1982 and 1992. The potential of the Elliot Lake mine was further indicated when Ontario Hydro, Duke Power Company and Tennessee Valley Authority all took up contracts for supplies. Thanks to this up-turn in demand, a large portion of mining operations at Elliot Lake was able to be reactivated.

As for Lord Lovell-Davis's claim that there was a world uranium shortage, the very opposite was true. In 1973 a report was published which revealed that owing to the lack of demand, all the major producing countries were holding large reserves of uranium in stockpiles; as a result prices were at an all-time low. In May 1974 the journal Nucleonics Week quoted a uranium dealer as saying: "I don't see any physical shortage in terms of consumption between now or 1978 or 1979." The government's case for continuing with the contracts was, then, badly misinformed and ill-thought out and nowhere was this more painfully apparent than in Lord Lovell-Davis's concluding remarks to the House of Lords: "The fact is", he said, "that any successor state in Namibia would, we think, start with a distinct advantage on the basis of arrangements such as those obtaining between Namibia and United Kingdom companies, already in position and capable of mutual agreement." Exactly how long was likely to pass before this "distinct advantage" was felt by the people of Namibia, and whether they would want to extend any arrangement between British companies and the illegal South African administration, were questions which Lord Lovell-Davis did not pause to consider.

In February 1976 Labour's National Executive Committee opposed the Labour government's position, urging that the Rossing contracts should be cancelled or amended and that "immediate high level talks" should be arranged "to ensure alternative supplies". In the meantime the NEC argued, "support for the people of Namibia would best be demonstrated by Britain joining the UN Council for Namibia." Such considerations received no further discussion, however, as four months later on 21st June 1976 the Minister of Technology, Tony Benn, made clear the government's intention to import Namibian uranium. Dates for supply had already been agreed between the customer, British Nuclear Fuels Ltd, and the supplier, RTZ.

Questioned in the House of Commons by Frank Hooley MP on the schedule over which full delivery of the 7,500 tons under contract would be made, Mr Benn replied that first supplies would be completed in 1977 and would continue until 1982 as follows:

- 1977 1,125 1980 1,525

- 1978 1,125 1981 1,125

- 1979 1,475 1982 1,125

A final comment on the issue came significantly from Prime Minister Jim Callaghan, in July 1978. Asked in an interview with Associated Press whether the troubles in Southern Africa threatened supplies of raw materials, he replied: "Any prudent country ought to be looking for alternative sources of supply." In some quarters at least, the Prime Minister's words of wisdom were eventually acted upon: the Central Electricity Generating Board, (CEGB), Britain's main electricity utility and the ultimate benefactor of the Rossing uranium, had long been perturbed by RTZ's monopoly position and by its own heavy dependence on such a doubtful and political source of supply as the Rossing mine. While the Department of Energy and its Minister, Tony Benn, continued to defend the contracts, the CEGB, through its newly established body, the Civil Uranium Procurement Directorate, therefore set about finding new sources of uranium thus breaking the RTZ-Whitehall stranglehold. The CEGB's efforts to diversify have recently borne fruit, in the form of contracts, either agreed or near to being signed, with Australia and a number of Third World countries, in particular Niger. Whatever one's opinions are on nuclear power their success illustrates only too clearly the emptiness of the arguments used over the years by apologists for the Rossing contracts. While delivery dates slipped, prices renegotiated, and successive governments risked all the political embarrassment attached to RTZ's dealings in Namibia, reliable alternatives were available. Now that they have been found, it remains only for the government to sever its surviving links with the Rossing mine, and terminate the contracts. Unfortunately, since the election of a Conservative government in May 1979, such a prospect now seems as remote as ever.

Non-interference 1979

Shortly after the election, the question of the government's policy towards the Rossing contracts was raised with the new Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington. Speaking on his behalf, Foreign Office Private Secretary Stephen Wall replied: "The general policy of the British government on trade with South Africa and Namibia... is one of non-interference with normal commercial links... In the case of the contracts to which you refer.., the government does not consider that there is any international obligation for it to interfere." It is perhaps relevant to note that for the last four years of the Conservative Party's period in opposition Lord Carrington served as a non-executive director of RTZ. He continued to hold this position until his appointment as Foreign Secretary.

Looking back over the policies of successive British governments' to the Rossing contracts, the following points should be made:

- The Labour government of 1966-70 was badly misinformed about the source of uranium supplies under its 1968 contract. If, as RTZ and the UKAEA claim, the Cabinet and MinTech were aware that Rossing was to be the source of supply, then serious investigation needs to be carried out even at this point in time, into the role played by civil servants and Ministers between 1966 and 1970. As in the case of Rhodesian oil sanctions, it seems clear that totally misleading information was allowed to pass uncorrected to the Cabinet.

- The Conservative government of 1970-74, and the Labour government of 1974-79 even more so, were uninformed about the availability of alternative sources of supply. Neither government looked into the one obvious alternative, Rio Algom. Since the statement made by Jim Callaghan to the Commons in 1974, British policy on Namibia has been completely reversed from that stated in 1966. This reversal has been entirely dictated by the government's contract with RTZ for Namibian uranium, which compromises all British discussions concerning the independence of Namibia.

- Britain's position is in direct breach of the terms of the UN Decree No.1. Whether or not the government choose to recognise the UN Resolutions and the 1971 opinion of the International Court, the Decree No.1 clearly allows for Namibian uranium to be seized and impounded during transit on behalf of the UN Council for Namibia.

- Foremost among the arguments against the Rossing contracts are their dire consequences for Britain's foreign policy, and indeed Britain's standing, in Southern Africa as a whole. Not only do the contracts render meaningless any pressure by Britain on South Africa to end its illegal occupation; but as Sonny Ramphal, Commonwealth Secretary-General, pointed out in the UN Security Council debate on Namibia in 1976, they also give Britain a 'vested interest' not only in the Rossing mine itself but in the continuation of South Africa's illegal administration. It is difficult to see how the country can progress towards free and fair elections and eventual independence as long as supplies of uranium continue under South Africa's occupation.

- This was the point made recently by the High Commissioner for Tanzania, Mr Amon Nsekala, when he denounced the men behind the Rossing contracts as delaying the liberation of Namibia and thus ensuring that when it came it would take longer and cost many more lives; the contracts, he claimed, only gave South Africa and several companies and their governments further reasons to resist or delay change: "The whole saga is morally outrageous. There are many in Africa and elsewhere who would say that the men who made the Rossing 'contracts' have blood on their hands."

Namibia's Response: SWAPO

In the South-African-sponsored elections in Namibia in 1978, the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) emerged as almost unchallenged victors. The elections however went unrecognised by the international community, who regarded the DTA simply as a front through which South Africa could extend its illegal control of Namibia. It was hardly surprising that SWAPO, the South-West Africa Peoples Organisation which leads the struggle for independence in Namibia, refused to take part in the elections. Formed on the 19th April 1960, SWAPO's aim was to oppose South Africa's apartheid administration: and despite repeated attempts by South Africa to destroy the movement, it continued to grow. By the mid 60's the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) had been formed in order to defend the Namibian people against South Africa's armed forces and to secure the total independence of Namibia. As a result of the Organisations mass support throughout the country, on the 13th December 1973 the UN General Assembly granted recognition to SWAPO as "the sole authentic representatives of the Namibian people", giving it full observer status at the General Assembly and rights of participation in all UN agencies.

SWAPO's views on the Rossing contracts deserve special attention, particularly as it is SWAPO that are likely to form the government of a future independent Namibia. An early statment concerning RTZ's operations was made by Mr Peter Katjavivi, then Official Representative for the United Kingdom and Western Europe. Speaking on the eve of RTZ's Annual General Meeting in 1975, he stated: "The presence of foreign companies like Rio Tinto Zinc in our country, their collaboration with the occupying South African regime. . . place them in the front line of the battle, on the side of our enemy. . . RTZ will have to pay the price for its years of piracy. .. SWAPO will judge such companies harshly when Namibia achieves independence." In SWAPO's opinion foreign investment is "one of the major factors contributing to the continuing presence of South Africa's illegal occupying forces." It comes as no great surprise therefore to find thit RTZ's Rossing mine is the largest single investment in Namibia.

"In this situation", claims SWAPO, "there can be no question of sitting on the fence. Those who have relations with the South African regime in Namibia and actively contribute by trade revenues to the regime are helping to perpetuate the illegal exploitation of our people."

In conclusion, the organisation once again called upon the British government to cancel the contract and disassociate itself from RTZ's operations in illegally occupied Namibia. "Britain must recognise that under the future legitimate government of Namibia, RTZ stands to forfeit all claim to its operations in our country."

Misrepresented

Sadly, instead of listening to these statements from the "sole authentic representatives" of the Namibian people, the British government have insisted that they know best. This high-handed attitude was bizarrely illustrated in 1975. It was in January of that year that Foreign Secretary Jim Callaghan visited Southern Africa where he met with representatives of SWAPO, members of the Zambian government, and others. On his return Callaghan stated to colleagues in the Labour Cabinet that it was his firm impression from a meeting with SWAPO that the movements representatives there had indicated that what ever they said publicly they wanted to contracts to go ahead, their public statements Callaghan maintained should be ignored. The Foreign Secretary's claim was later traced back to a meeting between himself and two SWAPO representatives which took place in Lusaka. But sources who have seen the official Foreign Office record of the meeting say that Callaghan's later account of the SWAPO position was completely unfounded: nowhere in the record was they any suggestion from SWAPO that the contracts should be continued.

For some reason, however, Callaghan's mysterious claim seems to have stuck: in September 1974 it was repeated by Mr Alex Eadie, a senior civil servant at the Department of Energy (which had replaced MinTech as the department dealing with the contracts). In a letter to Mr Frank Hooley MP it was once again asserted that SWAPO approved of Labour's decision to keep the contracts.

A short time later the Minster of State at the Foreign Office, David Ennals, explained in a letter to Mr Alex Kitson, the Executive Officer of the Transport and General Workers' union, that: "We are giving substantially increased political and practical help to SWAPO... this places the Labour government firmly on the side of those seeking liberation in Namibia.. . If Namibia achieves independence in the near future (which of course is what we must all continue to work for) then the economic value of the AEA-RTZ contract will be of enormous importance to the new nation. Given the possibility of rapid constitutional change in Namibia, it is our view that on balance the AEA-RTZ contract is in the interest of both Namibia and Britain.

Although the contents of the two letters did not reach SWAPO until March 1977, they immediately issued an aide memoire denying the British government's claim: "It has been brought to the attention of SWAPO that the British government has been claiming that the contract ... for deliveries of Namibian uranium for the British nuclear power programme has been condoned by SWAPO and that the opening up of the Rossing mine is in the interests of the people of Namibia... SWAPO categorically refuse to accept the right of the British government, or any other government, to decide what is or is not in the interests of the people of Namibia. We totally reject the assumption which lies behind this falsified claim to decide the future of a territory still struggling for self-determination and independence. The British government has continually tried to misrepresent our position, and we understand that this is still continuing." SWAPO also took the opportunity of once more calling upon the government to terminate the contracts, reminding them that under international law they were "obliged to cease all dealings with the illegal regime in our country."

SWAPO had good reason to resent Callaghan's misrepresentation of their views; for it was such a claim of SWAPO approval at the 1974 OPB meeting that had persuaded Cabinet to go back on the Party's 1973 Conference pledge and allow the contracts to go ahead. In August 1978, while South Africa stepped up hostilities by her armed forces against the people of Namibia, Mr Shapua Kaukunga, SWAPO's representative for Western Europe, spoke out, claiming that "while there is no international agreement on the question of Namibia, the United Nations Decree on Natural Resources must apply. All mining titles and prospecting rights issued after 1966 are illegal."

Successive Labour and Conservative governments vacillated over the Rossing deals, one moment claiming that they would be of "enormous importance" to an independent Namibia, the next moment denying that any "international obligation" exists to interfere with them in any way. By contrast, SWAPO's position has always been clear and consistent: an unmistakable call upon the British government to cancel the contracts.

RTZ Exposed

As the company directly responsible for ensuring delivery of the British government's uranium supplies, RTZ have made a number of statements about the contracts. These have focused on the origins of the contracts, the role of the UN, the company's relations with SWAPO, and British government policy. In May 1977 Sir Mark Turner, RTZ's chairman, confirmed that as far as the company were concerned, Rossing had never been the only available source of Britian's uranium. When asked by a shareholder at RTZ's Annual General Meeting if, in that case, the information given to the British Cabinet had been false, Sir Mark replied, diplomatically, "It was not correct. That is all I can answer."

Over the possibility of whether SWAPO might emerge as the future independent government of Namibia, and whether the company had therefore discussed its plans with them, Sir Val Duncan was unforthcoming: it was "rather difficult" for him "to indulge in conversation or negotiations and so forth with an organisation which is not actually representative of Namibia's people." But wasn't it therefore somewhat arrogant of RTZ to assume that they were necessarily "the organisation" to decide what was in the best interests of Namibia? The point was never answered Sir Mark Turner's feelings about SWAPO were made equally clear in 1977, when he asked: "Why must we talk, if I may say so, in a slightly trendy way about SWAPO eternally, when as far as I can see we've yet to see what the people of Namibia want?"

Both the late Sir Val Duncan and Sir Mark Turner have therefore dismissed discussions with SWAPO out of hand; just how a future SWAPO-dominated independent government of Namibia will look on RTZ remains to be seen. On the question of the United National authority to administer Namibia, the company have no doubts at all. Sir Val stating in 1975: "I question the authority of the United Nations to decide the future of all (Namibia's) people above their heads." Asked whether the company had taken any legal advice on the question of the UN Decree No.1, Sir Val replied: "I am not prepared to fail to deliver to the United Kingdom and others under a contract solemnly entered into for the provision of uranium from South-West Africa. I am therefore not prepared to take any notice of what the United Nations says about that. . If that involves disagreement with some of the Resolutions in the United Nations, I regret that, but that is their problem and I say that to you quite clearly." Were RTZ, then, not worried at the thought of their uranium being seized by the UN in transit? "Yes, I see," replied Sir Val, "Well, you may feel that perhaps the United Nations Navy is not all that efficient."

Shortly after South Africa tried to establish an unrepresentative assembly in Namibia in 1977, Sir Mark Turner was asked whether it would not be wise for RTZ to seek UN authorisation for their mining work; he replied: "I will not give any undertaking about approaching the United Nations, and we have no plans to do so."

Despite the blunt disregard for the UN's authority by Sir Val Duncan and Sir Mark Turner, the overthrow of Portuguese colonial rule in Mozambique and Angola, caused RTZ to re-assess the changing situation in Southern Africa. Responding to the possible removal of South Africa's illegal occupation, and the emergence of a SWAPO led independent government in Namibia, Sir Mark attempted to dismiss the value of the world's largest uranium mine to RTZ's long term future. The fact that SWAPO's control of the mine would jeopardise supplies of uranium to the British government and other western customers, was not the main concern of RTZ. Commenting to the Sunday Times on the 23rd July 1978, Sir Mark stated: "Rossing is not so large as to have a major effect on our survival. You don't like shrugging off things, but this is shruggable, I assure you." Whatever happened in Namibia RTZ planned to survive. "Every company makes mistakes" concluded Sir Mark, "if we didn't we wouldn't be alive".

While the policy of the British Government, directly influenced by the Rossing contracts, has been repeatedly used by RTZ as a means of defending their Rossing operations, the same policy has also been used as a means of dismissing both SWAPO and the United Nations administration of Namibia.

Energy Connection - South Africa

South Africa has always depended heavily on oil imports to fuel its domestic and industrial needs. Until the overthrow of the Shah in 1978, 90 per cent of its oil requirements had been met by Iran; but when the people's revolution brought a new Iranian government to power, it followed the policy of other Arab members of OPEC in imposing an oil embargo on South Africa. As a result the Pretoria Government found their entire economy severely threatened and efforts the replace Iranian oil with supplies from elsewhere have proved difficult and costly. Brunei remains the only country now openly selling oil to South Africa, but this small country is able to supply no more than 5 per cent of the apartheid regime's present needs. For South Africa the search for alternative forms of energy is now more pressing and crucial than ever before.

Nuclear power is one obvious answer - and with the Rossing mine being the largest uranium mine in the world, with an estimated lifespan of 25 years and sufficient reserves to provide for the production of 100,000 tons of uranium oxide, it cannot be ruled out that Rossing's vast deposits will not one day be used to fuel South Africa's nuclear power programme. A report in The Guardian in September 1976 converted the hypothesis into fact, stating that although uranium from Rossing would be supplied to Britain and Europe after 1977, "South Africa would not receive uranium from that source until 1980." Sir Mark Turner was questioned about the report, but denied that uranium from Rossing would be supplied to South Africa: "Where the Guardian gets that information from is their affair. It is not correct." It would actually be most odd if the information was not correct, since it came from none other that Rio Tinto South Africa, a 100 per cent, directly-owned subsidiary of RTZ!

Sir Mark's categorical denial overlooks a further factor: under South Africa's Atomic Energy Enrichment Act No.37 of 1974, the country's Uranium Enrichment Corporation can step in at any time and avail itself of all uranium resources in its area of control; for as long as South Africa continues to occupy Namibia, this area includes RTZ's mine at Rossing. It is therefore quite impossible for Sir Mark Turner to guarantee no uranium from Rossing will be suppled to South Africa. As the Act makes clear: "The objects of the Uranium Enrichment Corporation are: to hold, manage, develop, let or hire, or buy... or sell or otherwise deal with, ... immovable property of whatever kind, including source material and special nuclear material (as defined in Section I of the Atomic Energy Act) stocks, shares, bonds, debentures... and any interest in anybody of persons corporate and incorporate." In addition the Corporation can also take steps: "to act as the manager or secretary of any company, and to appoint any person to act on behalf of the Corporation as a director, or to act in any other capacity in relation to any company."

The Uranium Enrichment Corporation can therefore direct Rossing Uranium Ltd to supply whatever amount of uranium South Africa may require for its enrichment plant at Palindaba, near Johannesburg. Rossing's uranium resources are also covered by the South African Atomic Energy Act of 1948, which allows for existing export contracts to be cancelled at any time. South Africa acquired nuclear technology in the face of considerable international opposition, and it is a serious possibility that the Pretoria government would use its uranium supplies not solely for peaceful purposes, but for the building of nuclear weapons. In this case, the uranium produced at Rossing under RTZ's contracts with the British government could quite possibly be used directly to fuel South Africa's war machine. It is surely significant, therefore, that South Africa has refused to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

According to a report by South Africa's Foreign Affairs Association in 1977, "South Africa's production of U308 should reach 15,000 tons (including that from Rossing) by 1985." Should the South African government decide that they need further supplies of uranium at any time between now and 1982, the year in which the deliveries to Britain are scheduled to end, there would be nothing that either Britain or RTZ could do to prevent them taking control of supplies from Rossing. Certainly, the bland assurances of RTZ's chairman, Sir Mark Turner, would count for very little.

The Rossing Mine