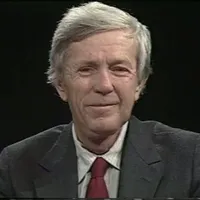

Michael Harrington

(political activist, academic, writer) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Edward Michael Harrington Jr. 24 February 1928 |

| Died | 31 July 1989 (Age 61) |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago, Yale Law School |

| Founder of | Democratic Socialists of America |

Michael Harrington was an American democratic socialist and writer, perhaps best known as the author of "The Other America". He was also a political activist, theorist, professor of political science, and radio commentator.

Michael Harrington was a founding member of the Democratic Socialists of America, and the DSA's most influential early leader.

Contents

Biography

Early life and education

Michael Harrington was born in St Louis, Missouri, on 24 February 1928, to an Irish-American family. He attended Roch Catholic School and St Louis University High School, where he was a classmate (class of 1944) of Thomas Anthony Dooley III. He later graduated from College of the Holy Cross and the University of Chicago (MA in English literature), and attended Yale Law School.

As a young man, Harrington was interested in both leftist politics and Catholicism. He joined Dorothy Day's Catholic Worker Movement, a communal movement that stressed social justice and nonviolence. Harrington enjoyed arguing about culture and politics, and his Jesuit education had made him a good debater and rhetorician.

Harrington was an editor of the newspaper Catholic Worker from 1951 to 1953, but he soon became disillusioned with religion. Although he always retained a certain affection for Catholic culture, he ultimately became an atheist.

Career

Harrington's estrangement from religion was accompanied by an increasing interest in Marxism and secular socialism. After leaving the Catholic Worker, Harrington became a member of the Independent Socialist League (ISL), a small organisation associated with the former Trotskyist activist Max Shachtman. Harrington and Shachtman believed that socialism, which they believed implied a just and fully democratic society, could not be realised by authoritarian communism, and were fiercely critical of the "bureaucratic collectivist" states in Eastern Europe and elsewhere.[3]

In 1955, Harrington was placed on the FBI Index, whose master list contained more than 10 million names in 1939. From the 1950s through to the 1970s, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover added an untold number of names of US liberation activists he considered "dangerous characters", to be placed in detention camps in case of a national emergency. Later, Harrington was added to the master list of Nixon political opponents.

After Norman Thomas's Socialist Party absorbed Shachtman's ISL in 1957, Harrington endorsed Shachtman's strategy of working as part of the Democratic Party rather than sponsoring candidates as Socialists. Although Harrington identified personally with the socialism of Thomas and Eugene Debs, the most consistent thread running through his life and his work was a "left wing of the possible within the Democratic Party."

Harrington served as the first editor of New America, the official weekly newspaper of the Socialist Party-Social Democratic Federation, founded in October 1960. In 1962, he published "The Other America: Poverty in the United States", a book that has been credited with sparking John F. Kennedy's and Lyndon Johnson's "War on Poverty". For "The Other America", Harrington was awarded a George Polk Award and The Sidney Award. He became a widely read intellectual and political writer, in 1972 publishing a second bestseller, Socialism. His voluminous writings included 14 other books and scores of articles, published in such journals as Commonweal, Partisan Review, The New Republic, Commentary magazine, and The Nation.

Harrington often debated classical liberals/libertarians like Milton Friedman and conservatives like William F. Buckley, Jr. He also debated younger left-wing radicals.

Harrington was present in June 1962 at the founding conference of Students for a Democratic Society. In clashes with Tom Hayden and Alan Haber, he argued that their "Port Huron Statement" was insufficiently explicit about excluding communists from their vision of a New Left. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. called Harrington the "only responsible radical" in America. Ted Kennedy said, "I see Michael Harrington as delivering the Sermon on the Mount to America," and "among veterans in the War on Poverty, no one has been a more loyal ally when the night was darkest."

By the early 1970s, the governing faction of the Socialist Party continued to endorse a negotiated peace to end the Vietnam War, a stance that Harrington came to believe was no longer viable. The majority changed the organisation's name to Social Democrats, USA. After losing at the convention, Harrington resigned and, with his former caucus, formed the Democratic Socialist Organising Committee. A smaller faction, associated with peace activist David McReynolds, formed the Socialist Party USA.

Harrington was appointed a professor of political science at Queens College in Flushing, New York City, in 1972. He wrote 16 books and was named a distinguished professor of political science in 1988. Harrington is also credited with coining the term neoconservatism in 1973.

Harrington said that socialists had to go through the Democratic Party to enact their policies, reasoning that the socialist vote had declined from a peak of approximately one million in the years around World War I to a few thousand by the 1950s. He considered running for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1980 against President Jimmy Carter, but decided against it after Senator Ted Kennedy announced his campaign. He later endorsed Kennedy and said, "if Kennedy loses or is driven out of this campaign, it will be a loss for the left".

In 1982, the Democratic Socialist Organising Committee merged with the New American Movement, an organisation of New Left activists, forming the Democratic Socialists of America. It was the principal US affiliate of the Socialist International, which includes socialist and labour parties such as the Swedish and German Social Democrats and the British Labour Party, until it voted to leave in 2017. Harrington remained chairman of DSA from its inception to his death.

During the 1980s, Harrington contributed commentaries to National Public Radio.

Death

Michael Harrington died of esophageal cancer in Larchmont, New York, on 31 July 1989.

Political views

Michael Harrington embraced a democratic interpretation of the writings of Karl Marx while rejecting the "actually existing" systems of the Soviet Union, China and the Eastern bloc. In the 1980s, Harrington said:

- Put it this way. Marx was a democrat with a small "d". The Democratic Socialists of America envision a humane social order based on popular control of resources and production, economic planning… and racial equality. I share an immediate program with liberals in this country because the best liberalism leads toward socialism. […] I want to be on the left wing of the possible.

- Harrington made clear that even if the traditional Marxist vision of a marketless, stateless society was impossible, he did not understand why this had to "result in the social consequence of some people eating while others starve".

Before the Soviet Union's collapse, the DSA voiced opposition to that nation's bureaucratically managed economy and control over its satellite states. The DSA welcomed Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms in the Soviet Union. Sociologist Bogdan Denitch wrote in the DSA's Democratic Left (quoted in 1989):

- The aim of democrats and socialists should be… to help the chances of successful reform in the Soviet bloc. […] While supporting liberalisation and economic reforms from above, socialists should be particularly active in contacting and encouraging the tender shoots of democracy from below.

Harrington voiced admiration for German Social Democratic Chancellor Willy Brandt's Ostpolitik, which sought to reduce antagonism between Western Europe and Soviet states.

Bernt Carlsson

Michael Harrington wrote an Obituary to his friend Bernt Carlsson that was published in the Los Angeles Times on 26 December 1988:

- "Lost On Flight 103: A Hero To The Wretched Of The World"

- "It was not an accident that my friend Bernt Carlsson, the UN Commissioner for Namibia, was killed in the crash of Pan American World Airways Flight 103.

- "Of course, it was a cruel and capricious fate that struck at Carlsson and his fellow passengers. But in Bernt's case it was part of a pattern - the kind of thing that might happen to a man who had spent his life ranging the Earth in search of justice and peace. And that life itself was emblematic of a Swedish socialist movement that has made solidarity with the wretched of the world a personal ethic.

- "Carlsson was returning home to New York for the signing of the agreement on Namibian independence, the culmination of his most recent mission. Before that he was a roving ambassador. From 1976 to 1983 he had been the general secretary of the Socialist International when that organisation was reaching out to the Third World as never before.

- "There had been so many flights, so many trips to the dangerous places like the Middle East and the front-line states of Southern Africa - even a brush with "terrorism" when Issam Sartawi, a Palestinian moderate, was murdered in the lobby of the Portuguese hotel at which the Socialist International was holding its congress in 1983. It was not inevitable that Carlsson be on a plane that, some suspect, was the target of fanatics, but it was not surprising - not the least because he came from a movement that made peace-making a way of life.

- "I sometimes think that if these Swedish men and women did not exist, the world would have to invent them. So it was that the United Nations gave Carlsson's mentor, the late Olof Palme, the impossible task of negotiating an end to the Iran-Iraq War. And why, as I saw firsthand at a meeting in Botswana, the Swedish prime minister was deeply mourned in black Africa. I had joked with Palme after a visit to Dar-es-Salaam in 1976 that the typical Tanzanian must be blond-haired and blue-eyed because of all the Swedes I encountered in that city.

- "It was Carlsson's friend and contemporary, Pierre Schori, who had played a major role in setting up the catalytic meeting in Stockholm between Yasser Arafat and five American Jews. I saw Swedish Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson in Paris on the day before that event, and he clearly regarded it as a serious governmental priority. Because the Swedish socialist commitment to peace-making sometimes requires criticism of the United States, there were those who said that its activists were "anti-American." When Palme was assassinated, practically every obituary remembered that he had marched with the North Vietnamese ambassador in a famous Stockholm rally against the American war; only one mentioned that, around the same time, the Swedish leader had publicly demonstrated in solidarity with the dissident communists of Czechoslovakia and against the Soviet invasion of their country.

- "Bernt Carlsson, like Palme and his other comrades, opposed Washington's policies and yet he deeply admired Americans, particularly their egalitarian irreverence. I remember vividly when Carlsson and I were in Managua in 1981 on a Socialist International mission to defend the revolution against Washington's intervention. Our group was led by Spanish Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez and former Venezuelan President Carlos Andres Perez, which guaranteed that it was taken with the utmost seriousness by the Sandinistas.

- "Carlsson was utterly firm in his opposition to American destabilisation. But then, to underline his commitment to democracy, he went to the offices of the opposition newspaper, La Prensa, and took out a subscription.

- "This gentle, shy, soft-spoken man with a soul as tough as steel was the true son of a movement that has proved that the conscience of a small nation can affect the superpowers.

- "In Jewish legend, a handful of the just keep the world from being destroyed. One of them died on Pan Am Flight 103, and many of them, like the blond-haired, blue-eyed people I saw in Dar-es-Salaam, seem to be Swedish."[1]

Works

- The Other America: Poverty in the United States. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

- The Retail Clerks. New York: John Wiley, 1962.

- The Accidental Century. New York: Macmillan, 1965.

- "The Politics of Poverty," in Irving Howe (ed.), The Radical Papers. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1966; pp. 122–43.

- The Social-Industrial Complex. New York: League for Industrial Democracy, 1968.

- Toward a Democratic Left: A Radical Program for a New Majority. New York: Macmillan, 1968; Baltimore: Penguin, 1969 paperback ed., with new afterword.

- Socialism. New York: Saturday Review Press. 1972. ISBN 978-0-84150141-6.

- Fragments of the Century: A Social Autobiography. New York: Saturday Review Press, 1973.

- Twilight of Capitalism. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977.

- The Vast Majority. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977.

- Tax Policy and the Economy: A Debate between Michael Harrington and Representative Jack Kemp, April 25, 1979., with Jack Kemp, New York: Institute for Democratic Socialism, 1979.

- James H. Cone, "The Black Church and Marxism: what do they have to say to each other", with comments by Michael Harrington, New York: Institute for Democratic Socialism, 1980.

- Decade of Decision: The Crisis of the American System. New York: Touchstone, 1981.

- The Next America: The Decline and Rise of the United States. New York: Touchstone, 1981.

- The Politics at God's Funeral: The Spiritual Crisis of Western Civilization. New York: Henry Holt, 1983.

- The New American Poverty. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1984.

- Taking Sides: The Education of a Militant Mind. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1985.

- The Next Left: The History of a Future. New York: Henry Holt, 1986.

- The Long Distance Runner: An Autobiography. New York: Henry Holt, 1988.

- Socialism: Past & Future, New York: Arcade Publishing, 1989

References

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here