Private Eye

(Satirical news magazine) "[https" has not been listed as valid URI scheme. | |

|---|---|

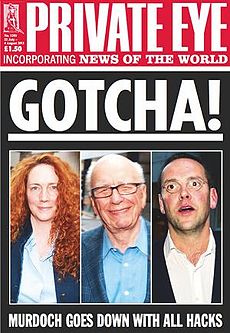

Cover of Private Eye from July 2011, making ironic use of a notorious headline from The Sun newspaper in 1982 | |

| Formation | 1961 |

| Founder | • Christopher Booker • Andrew Osmond • Willie Rushton • Peter Usborne and others |

| Headquarters | 6 Carlisle Street, London, W1D 3BN, UK |

| Member of | Melissa Zimdars/List |

Private Eye is a fortnightly British satirical and current affairs magazine based in London and edited by Ian Hislop.

Since its first publication in 1961, Private Eye has been a prominent critic and lampooner of public figures and entities that it deems guilty of any of the sins of incompetence, inefficiency, corruption, pomposity or self-importance and it has established itself as a thorn in the side of the British establishment.

It is Britain's best-selling current affairs magazine,[1] and such is its long-term popularity and impact that many recurring in-jokes from Private Eye have entered popular culture.

Contents

History

The forerunner of Private Eye was a school magazine, The Salopian, edited by Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Christopher Booker and Paul Foot at Shrewsbury School in the mid-1950s. After National Service, Ingrams and Foot went as undergraduates to Oxford University, where they met their future collaborators Peter Usborne, Andrew Osmond,[2] John Wells and Danae Brook, among others.

The magazine proper began when Peter Usborne learned of a new printing process, photo-litho offset, which meant that anybody with a typewriter and Letraset could produce a magazine. The publication was initially funded by Osmond and launched in 1961. It was named when Andrew Osmond looked for ideas in the well known recruiting poster of Lord Kitchener (an image of Kitchener pointing with the caption "Wants You") and, in particular, the pointing finger. After the name Finger was rejected, Osmond suggested Private Eye, in the sense of someone who "fingers" a suspect. The magazine was initially edited by Christopher Booker and designed by Willie Rushton, who drew cartoons for it. Its subsequent editor Richard Ingrams, who was then pursuing a career as an actor, shared the editorship with Booker, from around issue 10, and took over at issue 40. At first Private Eye was a vehicle for juvenile jokes: an extension of the original school magazine, and an alternative to Punch magazine. However, according to Booker, it simply got "caught up in the rage for satire".

After the magazine's initial success, more funding was provided by Nicholas Luard and Peter Cook, who ran "The Establishment" – a satirical nightclub – and Private Eye became a fully professional publication.

Others essential to the development of the magazine were Auberon Waugh, Claud Cockburn (who had run a pre-war scandal sheet, The Week), Barry Fantoni, Gerald Scarfe, Tony Rushton, Patrick Marnham and Candida Betjeman. Christopher Logue was another long-time contributor, providing a column of "True Stories" featuring cuttings from the national press. The gossip columnist Nigel Dempster wrote extensively for the magazine before he fell out with the editor and other writers, and Paul Foot wrote on politics, local government and corruption.

Ingrams continued as editor until 1986, when he was succeeded by Ian Hislop. Ingrams is chairman of the holding company.[3]

Nature of the magazine

Private Eye often reports on the misdeeds of powerful and notable individuals and has received numerous libel writs. These include three issued by James Goldsmith (known in the magazine as "(Sir) Jammy Fishpaste") and several by Robert Maxwell (known as Captain Bob), one of which resulted in the award of costs and reported damages of £225,000, and attacks on the magazine through the publication of a book, Malice in Wonderland, and a one-off magazine, Not Private Eye, published by Maxwell.[4] Its defenders point out that it often carries news that the mainstream press will not print for fear of legal reprisals or because the material is of minority interest.

Unearthing scandals and breaking news

Some contributors to Private Eye are media figures or specialists in their field who write anonymously, often under humorous pseudonyms. Stories sometimes originate from writers for more mainstream publications who cannot get their stories published by their main employers.

A financial column, "In the City", written by Michael Gillard, has generated a wide city and business readership as a large number of financial scandals and unethical business practices and personalities were first exposed there.

Recurring in-jokes

The magazine has a number of recurring in-jokes and convoluted references, often comprehensible only to those who have read the magazine for many years. They include references to controversies or legal ambiguities in a subtle euphemistic code, such as replacing "drunk" with "tired and emotional", or using the phrase "Ugandan discussions" to denote illicit sexual exploits; and more obvious parodies utilising easily recognisable stereotypes, such as the lampooning as "Sir Bufton Tufton" of Conservative MPs viewed to be particularly old-fashioned and intellectually lazy. Such terms have sometimes fallen into disuse as their hidden meanings have become better known.

The first half of each issue of the magazine, which consists chiefly of reporting and investigative journalism, tends to include these in-jokes in a more subtle manner, so as to maintain journalistic integrity, while the second half, more geared around unrestrained parody and cutting humour, tends to present itself in a more confrontational way.

Layout and style

Private Eye has lagged behind other magazines in adopting new typesetting and printing technologies. At the start it was laid out with scissors and paste and typed on three IBM Executive typewriters – italics, pica and elite – lending an amateurish look to the pages. For some years after layout tools became available the magazine retained this technique to maintain its look, although the three older typewriters were replaced with an IBM composer. Today the magazine is still predominantly in black and white (though the cover and some cartoons inside appear in colour) and there is more text and less white space than is typical for a modern magazine. The former "Colour Section" was printed in black and white like the rest of the magazine: only the content was colourful.

Special editions

The magazine has published a series of independent special editions dedicated to news reporting of particular current events, such as government inadequacy over the 2001 UK foot and mouth crisis, the conviction in January 2001 of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for the 1988 Lockerbie bombing (Lockerbie: the flight from justice, May/June 2001), and the MMR vaccine (The MMR: A Special Report, subtitled: "The story so far: a comprehensive review of the MMR vaccination/autism controversy" 2002).

Another special issue was published in September 2004 to mark the death of long-time staff member Paul Foot.[5]

Lockerbie Suspect Pursuit

Private Eye has covered the Lockerbie disaster story in detail over the past twenty six years. In May/June 2001, a special edition of the magazine was published, entitled "Lockerbie - The Flight From Justice" and written by Paul Foot - with help from John Ashton, Robert Black and Tam Dalyell and from Lockerbie relatives (Pamela Dix, John Mosey and Jim Swire).[6] Issue 1404, published on 28 October 2015, carried the following article on page 39 entitled "Lockerbie Suspect Pursuit" (believed to have been witten by John Ashton):

The announcement earlier this month that the Scottish police are pursuing two new Libyan suspects over the Lockerbie bombing appeared, at first glimpse to be a vindication of the highly controversial conviction of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi: both men were associates of his. Indeed one of them, Abu Agila Mas'ud, had on at least three occasions travelled on the same flights as Megrahi – including the morning of December 21, prior to the blast on board Pan Am 103. The pair flew out of Malta, where the prosecution claimed the bomb originated.

Further evidence from a Libyan informant and the files of the former East German security service, the Stasi, suggested that Mas'ud was also the technical expert responsible for a bomb used in the La Belle disco in Berlin April 1986, two years before Lockerbie, which killed three people, including two US servicemen. Mas'ud is now in a Tripoli prison, convicted of building car bombs during Libya’s revolution. The other named suspect, Abdullah al-Senussi, appears to be in the frame for no better reason than he was the former Libyan security chief and a relative by marriage of Megrahi’s.

Perhaps embarrassingly for the police and the Crown Office, the “breakthrough” came not from them, but through the painstaking efforts of a relative of a Lockerbie victim. American Ken Dornstein, whose brother was one of the 270 who perished in the blast, made a three-part documentary "My Brother’s Bomber", recently broadcast by America’s PBS Frontline series. In fact neither name is new to the Lockerbie investigation. Senussi was named in a US State Department fact sheet that accompanied Megrahi’s indictment and Scottish police statements show that Mas'ud became a suspect in early 1991, but it was apparently decided that there was not enough evidence against him.

What Dornstein spotted was that although Megrahi had always denied knowing Mas'ud, he was seen greeting Megrahi on his return to Libya, when he was released early on compassionate grounds.

The documentary provided a strong circumstantial case against Mas'ud. But so much of any case against him must rely upon the same flawed evidence that persuaded the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission – and others before them – to conclude Megrahi may have been wrongly convicted (Eyes passim ad nauseam). That included the dodgy claim that the bomb began its journey from Malta via Frankfurt, when there was compelling evidence that it was loaded at Heathrow. Not to mention the supposed forensic evidence linking the bomb to the Libyans. New testing of a tiny fragment of circuit board, showed it was no match for timing devices known to have been bought by Libya.

Then there is a further problem: the main witness implicating Mas'ud in the German disco bombing is a Libyan Musbah Eter, who German media later found out was working for the CIA. Now, 20 years later, Eter is claiming that both Megrahi and Mas'ud are also responsible for the Lockerbie bombing. Quite why he kept quiet for so long remains a mystery. Tellingly, perhaps, the Crown Office and Scottish police have failed to follow up the new scientific evidence, preferring instead to concentrate on leads that bolster the original conviction. Hardly surprising then, that some of the bereaved families like Jim Swire, father of Flora, remain sceptical that they will ever learn the truth.[7]

References

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Richard Ingrams interview" (PDF). Press Gazette. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2013.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "''Not Private Eye'', Tony Quinn". Magforum.com. 21 November 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2013.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "Paul Foot, radical columnist and campaigner, dies at 66"

- ↑ "Lockerbie - The Flight From Justice"

- ↑ "Private Eye reports on the latest Lockerbie claims"