Abdullah al-Senussi

(Spook) | |

|---|---|

Abdullah al-Senussi, formerly Libya’s intelligence chief and right-hand man of Muammar Gaddafi | |

| Born | 1949-12-05 Gira, Libya |

| Nationality | Libyan |

| Citizenship | Libyan |

Abdullah al-Senussi (born 5 December 1949) is a Libyan national who was the intelligence chief and distant relative of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, having married Gaddafi's sister-in-law. Al-Senussi is best known for his alleged role in the killing of more than 1,200 inmates at Tripoli's Abu Salim prison in 1996. He was also involved in the controversial rapprochement between Gaddafi's government and Britain and France in the early 2000s, which led to growing commercial ties.[1]

During the 2011 NATO bombing of Libya in support of the rebels, al-Senussi was indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) and accused of war crimes allegedly committed during the uprising against Muammar Gaddafi. On 16 May 2011, the ICC prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo announced that he was seeking an arrest warrant for Abdullah al-Senussi on charges of crimes against humanity.[2] He was reported to have been captured on several occasions but it was not until 5 September 2012 however that Mauritania, where he had taken refuge and been arrested, actually extradited al-Senussi to Libya. The new Libyan authorities were said to have paid Mauritania $200 million to hand him over in defiance of the ICC's arrest warrant, and undertook to put him on trial in Libya for crimes allegedly committed during the time he was Gaddafi's assistant.[3]

Contents

Death sentence

In October 2013, the BBC reported that the International Criminal Court had ruled that al-Senussi could be tried in Libya on the basis that "Libya is willing and able genuinely to carry out" investigations into Mr Senussi. Although Senussi's lawyers were appealing the ICC ruling, he appeared in a court in Libya for a pre-trial hearing on 19 September 2013.[4]

On 11 December 2013, his daughter Anoud al-Senussi said he should be brought to The Hague to face trial, warning that her father faced a show trial and death in Libya unless extradited. She said her father was being denied access to lawyers in his prison in Libya, where has been held since he was extradited from Mauritania. Anoud al-Senussi told Reuters she did not expect her father to be freed, but that she was hoping to secure for him a fair trial before "a fair court". A month earlier, Senussi's lawyer Ben Emmerson QC said:

- "He should be tried at the ICC, where he will not face the death penalty."

Pointing to the kidnapping by militias earlier this year of the new prime minister Ali Zeidan, they said that, two years on from the uprising, Libya was still too unstable to give a fair trial to a figure as prominent as Abdullah al-Senussi.[5]

On 28 July 2015, the BBC's John Simpson reported that a Libyan court had imposed the death sentence on Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and eight others including former head of intelligence Abdullah al-Senussi and former prime minister Baghdadi Mahmudi.[6] He is appealing against the sentence, given in a trial that was criticised for failing to meet international fair trial standards. Judgment on the appeal by Libya’s supreme court could take anything from two months to two years.

In October 2015, Ibrahim Aboisha, one of Senussi’s lawyers, said he had only heard about the renewed interest in the Lockerbie case from the media:

- “I have not discussed any pre-revolution matters with my client and I can’t just go straight to him and ask him about Lockerbie as it could come as a big shock. I would first need to see any official requests and discuss the matter with his family.”

Abdullah al-Senussi, who has appeared gaunt at the court hearings, has been held in solitary confinement since his extradition from Mauritania in 2012 at Tripoli’s high-security Hadba prison, along with other senior officials from the former regime.[7]

Rise and fall

According to The Guardian, Abdullah al-Senussi had a reputation for brutality since the 1970s. During the 1980s he was head of internal security in Libya, at a time when many opponents of Gaddafi were killed. Later, he had been described as the head of military intelligence, but it is unclear whether he actually held an official rank. In 1999 he was convicted in absentia in France for his role in the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772, a passenger plane flying over Niger that resulted in the death of 170 people. He is alleged to have been responsible for massacring 1,200 prisoners at the Abu Salim jail in 1996. He was also thought to have been behind an alleged plot in 2003 to assassinate Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia.

It was Senussi’s marriage to Muammar Gaddafi’s wife’s sister in the 1970s that saw him enter the elite circle of Libya’s leader and assume various roles including deputy chief of the External Security Organisation (ESO).[8]

WikiLeaks cables described him as being a confidant of Gaddafi who made "many of his medical arrangements". During the NATO attack on Libya, al-Senussi was blamed for orchestrating killings in the city of Benghazi and recruiting foreign mercenaries. He was believed to have extensive business interests in Libya.

On 1 March 2011, Libya's Quryna newspaper reported that Gaddafi had sacked him.[9]

On 21 July 2011, Libyan opposition sources claimed that al-Senussi had been killed in an attack by armed rebels in Tripoli; however, a few hours later the same sources recanted on their earlier claim and some even said he might have just been injured.[10]

On 30 August 2011, there were reports that both Senussi's son, Mohammed Abdullah al-Senussi,[11] and Muammar Gaddafi's son, Khamis, were killed during clashes with NATO and NTC forces in Tarhuna.[12] In October, Arrai TV, a pro-Gaddafi network in Syria, confirmed that Mohammed Senussi and Khamis Gaddafi had been killed on 29 August.[13] On 20 October, Niger foreign minister Mohammad Bazoum told Reuters that he had fled to Niger.[14] However, a Libyan fighter later told The Guardian that the rebels had possession of three other men who were in Gaddafi's convoy when he was killed and that he believed one them was Senussi.[15] The other two were identified as Gaddafi's slain son Mutassim and one of his military commanders Mansour Dhao, who was still alive and confirmed his identity, as well as details of Gaddafi's death, to Human Rights Watch while in the hospital. Dhao was earlier thought to have fled to Niger.

However, later reports surfaced that Senussi from his hideout in Niger was helping Saif al-Islam Gaddafi escape from Libya.[16] Senussi was reportedly captured on 20 November near the city of Sabha. It was afterwards reported that he would be taken to Tripoli to stand trial for charges of crimes against humanity, according to the National Transitional Council.[17] However, ICC chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo doubted Senussi was captured.[18] Libyan defence minister Osama al-Juwaily also stated that there was no evidence Senussi had been captured.[19] On 4 December 2011, Abdullah Nakir, a Libyan official, told Al Arabiya that al-Senussi was arrested and was being questioned about a secret nuclear facility Gaddafi was operating, but admitted that the Libyan government was unable to produce any photographs of him in custody.[20]

On 17 March 2012, news reports stated that Senussi had been arrested at Nouakchott airport in Mauritania.[21][22] The Libyan government is reported as having requested his extradition to Libya.[23]

In September 2012, Lebanese foreign minister Adnan Mansour and a Lebanese judge questioned him on the fate of Imam Musa Sadr.[24] On 5 September 2012, Mauritania extradited Senussi to Libyan authorities. Senussi is to be tried in Libya for crimes he allegedly committed during the time he was the close assistant to Gaddafi.[25]

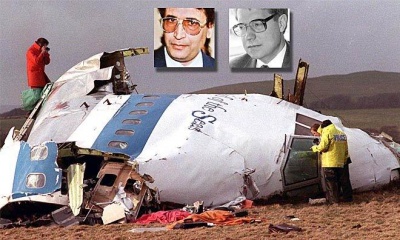

Lockerbie bombing

In January 2014, Scotland's Lord Advocate, Frank Mulholland, visited Tripoli to arrange for Scottish police officers to question Lockerbie bombing suspects after Libya dropped earlier objections. Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the only man convicted of the bombing, died in 2012 in Libya protesting his innocence. But Ben Emmerson QC, appointed to represent Senussi by the International Criminal Court (ICC), said Libya had so far refused him permission to visit his client. A senior member of Emmerson's legal team, Amal Alamuddin, said:

- "Any new inquiry into the events surrounding Lockerbie needs to be scrupulously fair, and this needs to start with Mr Senussi being given legal counsel during any interview with Scottish law officers."

Ben Emmerson called on Scottish police not to interview him as part of a new Lockerbie inquiry without a lawyer being present:

- "Mr al-Senussi has been held incommunicado without access to legal advice in respect of any proceedings. I am certain that you would wish any interview to be conducted between Mr al-Senussi and Scottish police officers to be scrupulously fair, putting its admissibility in subsequent proceedings beyond any doubt."[26]

Libya was reported to have appointed two officers to work with Scottish and American Lockerbie investigators, with the Justice Minister, Salah al-Marghani, saying:

- "We should know everything about what happened."

Emmerson, who represented the Wikileaks founder, Julian Assange, is also appealing against the ICC's decision in October that Libya could take the Senussi case, arguing that the country's turmoil raises doubts about its ability to hold a fair trial.[27]

Alleged co-conspirator

On 15 October 2015 Frank Mulholland, having recently met Attorney General of the United States Loretta Lynch in Washington to review progress made in the ongoing investigation into the Lockerbie bombing, announced that he had issued an International Letter of Request to the Libyan Attorney General in Tripoli which identifies two Libyans, Abdullah al-Senussi and Abu Agila Mas’ud, as suspects in the conspiracy to bomb Pan Am Flight 103. A Crown Office spokesman said:

- "The Lord Advocate and the US Attorney General are seeking the assistance of the Libyan judicial authorities for Scottish police officers and the FBI to interview two named suspects in Tripoli. The two individuals are suspected of involvement, along with Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, in the bombing of flight Pan Am 103 in December 1988 and the murder of 270 people."[28]

Mulholland's announcement followed Ken Dornstein's September 2015 film "My Brother's Bomber"[29] which was based on former SIO Stuart Henderson's list of ten names of people described as Megrahi's “unindicted co-conspirators” who had never been put on trial. Thought to be included in that list were former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and Swiss businessman Edwin Bollier whose firm MEBO manufactured electronic timers.[30] Top of Henderson's list was Gaddafi's former spy chief Abdullah al-Senussi, who was convicted in Tripoli of "crimes against humanity" in July 2015, and sentenced to death. The remaining seven were:

- Nasser Ali Ashour, the Armourer. A "smooth, cultured" spy who supplied Semtex and guns to the Provisional IRA for Gaddafi in the 1980s. Adrian Hopkins, the Irish skipper who helped smuggle the arms, told French police: "He spoke English with a very distinguished accent. He never looked you in the face, likes to parade, has small feet, wears Italian shoes, drinks whisky but does not smoke." He managed Libya's network of agents in the Mediterranean and hunted down Libyan dissidents throughout Europe. Now aged 68, his whereabouts are unknown.

- Mohammed Abouagela Masud (aka Abu Agila Mas’ud), the Technician. Introduced to a CIA undercover agent as an airline technician, he worked with Megrahi and Fhimah in Malta where the bomb was allegedly planted on a feeder flight in an unaccompanied Samsonite suitcase. The evidence against Mas'ud is thought to have been the subject of secret court hearings held behind closed doors in Valletta in 2012, at the request of the Crown Office. His whereabouts are unknown.

- Said Rashid, the Assassin. A former head of JSO's operations section and close friend of Gaddafi who went on to become a powerful government figure. He was killed in a shoot-out with rebels in February 2011 following a speech by the dictator's son, Saif. In 1983, Rashid was arrested in France in connection with the murders of Libyan dissidents in London, Bonn and Rome, but later released.

- Ezzadin Hinshiri, the Diplomat. Another senior JSO figure who became a top official and one of Gaddafi's most loyal lieutenants. He was killed along with 52 other regime supporters in an infamous massacre at a seafront hotel in Sirte in the final days of the uprising in April 2011.

- Badri Hussan, the Businessman. Set up a front company with Megrahi and rented an office in Zurich from Mebo, the Swiss firm linked to the timers used in the bombing. The firm's co-founder, Edwin Bollier, told the Lockerbie trial that he delivered a suitcase from Hussan to Hinshiri in Tripoli on December 17, 1988 - just days before the terror strike. Whereabouts unknown.

- Mohamed Marzouk and Mansour Omran Saber, the Missing Links. Arrested at Dakar airport in Senegal in February 1988 with Semtex, TNT and bomb triggers. They were released without charge. In 1991, a "brilliant, young" CIA analyst realised the triggers matched those used in the Lockerbie bombing, changing the entire course of the investigation. Whereabouts unknown.[31]

Henderson told Dornstein that if he could get to Libya it might be possible to track down the men who could then be brought to trial. Over the course of three trips to Libya starting in 2011, Dornstein sought out the eight men on the list, finally revealing that Abu Agila Mas’ud, imprisoned in Tripoli, was his main suspect.[32]

However, Middle East expert Jason Pack said the idea of Lockerbie investigators going to Libya to interrogate suspects in its current state of turmoil was an absurdity. Even if investigators did manage to gain access to the prisoners, Lockerbie campaigner Morag Kerr doubted that anything would be achieved:

- "Any case against Senussi and Mas’ud would be based on the same essential evidence that was used to convict Megrahi in the first place. But that evidence has been systematically dismantled and discredited over a number of years. If that were to be tested in court then against new suspects, I’m afraid I would be very doubtful it would even get to court."[33]

UTA Flight 772

On 19 September 1989, UTA Flight 772 exploded over the West African state of Niger killing all 170 passengers and crew. French investigators into the sabotage led by Juge Jean-Louis Bruguière blamed Libya.

The motive usually attributed to Libya for the UTA Flight 772 bombing is that of revenge against the French for supporting Chad against the expansionist projects of Libya towards Chad. Libya was understood to have considered this French support as "neo-colonialist".[34] The Chadian–Libyan conflict (1978–1987) ended in disaster for Libya following the defeat at the Battle of Maaten al-Sarra in the 1987 Toyota War. Muammar Gaddafi was forced to accede to a ceasefire ending his dreams of African and Arab dominance. Gaddafi blamed the defeat on French and US "aggression against Libya".[35]

Juge Bruguière obtained a confession from one of the alleged terrorists, a Congolese opposition figure, who had helped recruit a fellow dissident to smuggle the bomb onto the aircraft. This confession led to charges being brought against six Libyans.

Bruguière identified them as follows:

- Abdullah al-Senussi, brother-in-law of Muammar Gaddafi, and deputy head of Libyan intelligence;

- Abdullah Elazragh, Counsellor at the Libyan embassy in Brazzaville;

- Ibrahim Naeli and Arbas Musbah, explosives experts in the Libyan secret service;

- Issa Shibani, the secret agent who purchased the timer that allegedly triggered the bomb; and,

- Abdelsalam Hammouda, Senussi's right-hand man, who was said to have coordinated the attack.

Convicted in absentia

In 1999, the six Libyans were put on trial in the Paris Assize Court for the bombing of UTA Flight 772. Because Muammar Gaddafi would not allow their extradition to France, Abdullah al-Senussi and the other five Libyans were tried and convicted in absentia, and sentenced to life imprisonment.[36]

However, in "Manipulations Africaines" ("African Manipulations"), published in February 2001, journalist Pierre Péan investigated the sabotage of UTA Flight 772. He alleged that initial evidence pointed to Iran and Syria (acting through the Hezbollah movement), but that due to political context (notably the Gulf War), France and the United States tried to put the blame on Libya. Péan accused Juge Jean-Louis Bruguière of deliberately neglecting proof of Lebanon, Syria and Iran being involved to pursue only the Libyan trail. He also accused Thomas Thurman, an FBI political operative, of fabricating false evidence against Libya in the sabotage of both Pan Am Flight 103 and UTA Flight 772:

- "It is striking to note the similarity of the 'scientific' evidence discovered by the FBI's Tom Thurman in both the Lockerbie and UTA cases. Of the tens of thousands of pieces of debris collected at each disaster site, one lone piece of printed circuit was found and, miracle of miracles, in each case the fragment bore markings that allowed for positive identification: MEBO in the Lockerbie case and TY in the case of UTA Flight 772. Despite the common findings of the DCPJ, the DST and the Prefecture of Police crime laboratory, Juge Bruguière chose to believe Thurman, the expert in fabricating evidence."[37]

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:Call for US to give update on fourth Lockerbie suspect | Article | 18 December 2022 | Kathleen Nutt | Former Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill: "Britain and America know everything. I want the UK and US to be more open. Libya have offered up Abu Agila Masud. But Masud is smaller beer. The Lord Advocate should find out what progress is being made on bringing Abdullah Senussi to court." |

References

- ↑ "Gaddafi's right-hand man should not be underestimated"

- ↑ "ICC prosecutor seeks arrest warrant for Gaddafi"

- ↑ "Abdullah Al Senussi, Intelligence Chief For Former Libyan Leader Muammar Gaddafi, Arrested In Mauritania"

- ↑ "Gaddafi spy chief Abdullah al-Senussi in court"

- ↑ "Daughter of Libya's former spy chief calls for him to be tried in The Hague"

- ↑ "Libya trial: Gaddafi son sentenced to death over war crimes"

- ↑ "Libya may refuse to extradite Lockerbie suspects"

- ↑ "Profile Abdullah al-Senussi"

- ↑ "Libya uprising - Tuesday 1 March as it happened: part 2"

- ↑ "Updates, Libya February 17th"

- ↑ "Libya conflict: Bani Walid siege talks 'have failed'"

- ↑ "Is Gaddafi's Son Actually Dead?(International Business Times)

- ↑ "TV station mourns death of Gaddafi's son Khamis in Libya"

- ↑ "Gaddafi spy chief believed to be hiding in Niger"

- ↑ "Gaddafi's last words as he begged for mercy: 'What did I do to you?'"

- ↑ "Gaddafi son preparing to flee Libya: NTC official"

- ↑ "Gadhafi intelligence chief captured, Libya official says"

- ↑ "Doubts by ICC chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo"

- ↑ "Libya defence minister disputes Abdullah al-Senussi capture claims"

- ↑ "Al-Senussi, Libya’s ‘Black Box’, being questioned about suspected nuclear site"

- ↑ "Gaddafi spy chief Abdullah al-Senussi held in Mauritania"

- ↑ "Muammar Gaddafi's spy chief Senussi 'arrested in Mauritania'"

- ↑ "Libya demands handover of Gaddafi spy chief Senussi"

- ↑ "Mansour, Lebanese judge to question Sanousi on Sadr’s fate"

- ↑ "Mauritania 'extradites Libya ex-spy chief Abdullah al-Senussi'"

- ↑ "Scots police to question Gaddafi henchman"

- ↑ "Lockerbie bombing inquiry: lawyer warns police over al-Senussi interview"

- ↑ "Two new Lockerbie bombing suspects identified"

- ↑ “'My Brother’s Bomber': The compelling personal crusade to crack the terror plot behind the 1988 Lockerbie explosion"

- ↑ "The Avenger"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Seven new Libyans named"

- ↑ "My Brother's Bomber: The Libya Dossier"

- ↑ "Transcript of BBC Radio Scotland programme Good Morning Scotland," 17 October 2015, (17’20’’ to 29’37’’)

- ↑ "The French military role in Chad"

- ↑ "Disputes Raiders of the Armed Toyotas"

- ↑ "Manipulations Africaines: Les preuves trafiquées du terrorisme libyen" by Pierre Péan, Le Monde diplomatique, 5 March 2001

- ↑ "Fabricated Evidence of Libyan Terrorism" Excerpt from "African Manipulations" by Pierre Péan, Le Monde diplomatique, 5 March 2001