UK Independence Party

(Political party) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | UKIP |

| Founder | Alan Sked |

| Headquarters | Lexdrum House Newton Abbot, Devon |

| Leader | Gerard Batten |

| Eurosceptic, right-wing political party in the United Kingdom | |

The UK Independence Party (UKIP) is a hard Eurosceptic, right-wing political party in the United Kingdom. It currently has one representative in the House of Lords and three Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). It has three Assembly Members (AMs) in the National Assembly for Wales and one member in the London Assembly. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two Members of Parliament and was the largest UK party in the European Parliament.[1]

UKIP originated as the Anti-Federalist League, a single-issue Eurosceptic party established in London by the historian Alan Sked in 1991. It was renamed UKIP in 1993 but its growth remained slow. It was largely eclipsed by Sir James Goldsmith's Referendum Party until the latter's 1997 dissolution when Sked was ousted by a faction led by Nigel Farage. In 2006, Farage officially became leader and under his direction the party adopted a wider policy platform and capitalised on concerns about rising immigration, in particular among the White British working class. This resulted in significant breakthroughs at the 2013 local elections, 2014 European elections and 2015 General Election. The pressure UKIP exerted on the government was the main reason for the 2016 EU Referendum which led to the UK's commitment to withdraw from the European Union. Farage then stepped down as UKIP leader, and the party's vote share and membership heavily declined. Following repeat leadership crises, Gerard Batten took over. Under Batten, UKIP was characterised as moving into far-right territory, at which point many longstanding members – including Farage – left. Farage then launched the Brexit Party.

Contents

Rise in popularity

Nigel Farage, UKIP's leader from 2006 to 2009, was re-elected as leader on 5 November 2010.[2] Nigel Farage is a founding member of the party,[3] and has been a UKIP Member of the European Parliament (MEP) since 1999.[4]

Following UKIP's major gains in the May 2014 local council and Euro elections, some Tory backbenchers - including Eurosceptics Douglas Carswell, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Peter Bone - called for an electoral pact with UKIP at the 2015 General Election. But PM David Cameron quickly rejected the call, saying:

- "We are the Conservative Party. We don't do pacts and deals. We are fighting all out for an all-out win at the next election."[5]

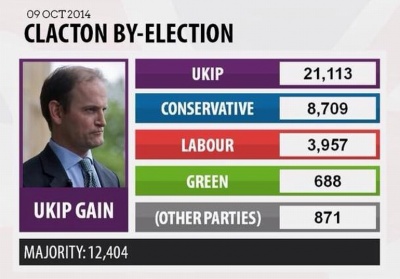

On 2 September 2014, in the first opinion poll published for the Clacton by-election, Tory fund-raiser Lord Ashcroft put UKIP candidate Douglas Carswell on 56 per cent, 32 points ahead of the Conservatives on 24 per cent. Labour were on 16 per cent, and the Liberal Democrats and Others on 2 per cent each.[6]

At the UKIP party conference in Doncaster in September 2014, the party said it would cut income tax from 40p to 35p for people earning up to £55,000 and promised to raise to £13,500 the amount people can earn before paying any income tax. In a plan to win the "blue-collar vote", Nigel Farage's party pledged to fund the changes by leaving the EU and cutting UK foreign aid by 85%. Nigel Farage said he expected UKIP to have "real influence" after the election and told the BBC it was important that people thinking of voting for UKIP knew what his party would be "fighting for" in the event of a hung Parliament next May. Farage addressed an estimated 2,000 activists at the conference at Doncaster Racecourse - which is near Labour leader Ed Miliband's constituency, making a direct appeal to Labour voters by claiming the opposition had failed to stand up for the people it was founded to represent.[7] On the last day of the conference, and on the eve of the Conservative Party conference, Tory MP Mark Reckless appeared on the platform and announced he would be following Douglas Carswell and defecting to UKIP.[8]

Deep political connections

Nafeez Ahmed writes that "a large bulk of UKIP’s funding boost came from former Tory donors, millionaire bankers, and corporate executives, pushing the fringe party to receive the third largest percentage of the vote."

“Unbeknown to many, UKIP too had early roots in Britain’s intelligence services.

In 2001, former Conservative Party chairman Norman Tebbit called for an independent inquiry into revelations that UKIP had been infiltrated by MI5. In a televised interview on BBC News, Tebbit said:

“A chap came to me and said UKIP had been infiltrated by the British intelligence services and then he gave me two names of people and from various ways I came to the conclusion that I was absolutely and completely certain that these people — although they had left the service and the Foreign Office some years earlier — in fact had been intelligence agents.”

As Tebbit explained in a Spectator article that even Douglas Murray recently endorsed, he “half-heartedly” made his “own inquiries” after a source inside UKIP raised the concerns with him, “and unexpectedly struck gold... I am perfectly sure that the individuals had been active agents, although both would claim to have retired some years ago.”

Tebbit had not suggested that UKIP’s leadership was aware of the intelligence operation. At the time, Nigel Farage admitted that he could not discount Tebbit’s allegations.”

Nafeez Ahmed (May 11, 2015) [9]

John Browne, former Vice President of UKIP, was an attendee of Le Cercle.

Electoral Success

In May 2014, UKIP became the first party in over a century other than Labour or the Conservatives to come first in a United Kingdom-wide election, with its performance in the 2014 European elections giving it 24 of the UK's 73 seats in the European Parliament.[10] Although UKIP has never won a seat in the House of Commons, it has three members in the House of Lords and holds one seat in the Northern Ireland Assembly.[11][12] The party's performance in the 2013 local elections, when it came fourth in the number of council seats won and third in nationwide vote share,[13] was called the "biggest surge for a fourth party" in British politics since the Second World War.[14]

Electoral Stitch Up

In a MailOnline article on 7 September 2014, Tory MP Jacob Rees-Mogg called for a pre-Election pact with UKIP and for Nigel Farage to be made Deputy Prime Minister in a future Tory/UKIP Coalition Government:

- In many ways the current Government has been highly successful. It has begun the long process of restoring sound money, made major reforms to a number of public services and managed to begin restructuring the bloated Welfare Bill. Unfortunately, this is not reflected in the opinion polls. Between them, the (small ‘c’) conservative parties have nearly 50 per cent, while the two major forces of the Left are on 42.5 per cent.

- About two-thirds of UKIP supporters are former Conservatives. Thus the split in the Tory family – demonstrated by Douglas Carswell’s defection last month – makes it difficult for the Tory/LibDem Coalition to win an Election, potentially paving the way for Ed Miliband to win despite having little more than one-third of the vote. The obvious answer is for the Tories and UKIP to do a pre-Election deal.

- In a first-past-the-post system there is no prospect of doing a post-Election pact; each party takes too many of its voters from the same pool so there would not be enough combined MPs to form a coalition. Now there are obstacles in the way of a pre-Election pact, but these are more emotional than rational. It is said that the two leaders do not like each other, but coalition has shown that Ministers from separate parties can work effectively with each other, and there is no obvious personal animosity between David Cameron and Nick Clegg or George Osborne and Danny Alexander. It is in the nature of politics that leaders attack each other, but that ought not unduly to upset a thick-skinned statesman.

- Despite being held back by coalition, the Prime Minister has still delivered some important Eurosceptic gains. He vetoed the fiscal compact, voted against Mr Juncker, managed to cut the EU budget and enshrined in law a referendum lock on future treaties. Against this he is idiosyncratically supporting the European Arrest Warrant, which is a notable aspect of the creation of a federal Europe. Nonetheless, this leaves the balance in his favour even if he seems sometimes to have responded to pressure.

- What is certain is that his promise of an in/out referendum if returned in 2015 is sincere and can only happen if he wins. This means that UKIP can achieve its main policy objective only if the Tories win the Election – yet it is the principal obstacle to this happening. Sheer bloody mindedness is stopping the conservative family from dominating the UK political scene to achieve what all of us want. Regrettably, the Clacton by-election will make it worse, as positions become more entrenched. Therefore, some people have started suggesting that nothing can be done until after an Election at which point there will be some re-alignment of the Right. This seems a defeatist view.

- David Cameron has the opportunity to solve the problem now if he is generous. The undoubted talents and charisma of Nigel Farage should be recognised. He appeals to not only traditional Conservative members but also to those who have felt disenfranchised, people who feel that politicians are part of a too-cosy establishment while UKIP is shaking it up. In some respects he appeals in a way that Boris Johnson does to those with Conservative values who are not necessarily Tory.

- Prior to the Election such an offer needs to help UKIP in its ambition to win parliamentary seats. This could start with the House of Lords where, in spite of its recent electoral success, no new UKIP peer has been created. It needs to be followed by deals in individual seats. There are a number vacant because of retirement, which may be suitable, as well as the ones where the Conservatives cannot expect to win and where UKIP is making inroads against Labour. After the Election, if this strategy were adopted, there would be four Cabinet posts available through the removal of the Liberal Democrats.

- Nigel Farage would be a much preferable Deputy Prime Minister to any true Conservative than Nick Clegg, while replacing Vince Cable with someone from UKIP would have a pleasant irony. Perhaps as a sign of good faith even the Minister for Europe could be a UKIP MP.

- If the Prime Minister were to do this he would suddenly have taken charge of events, no longer could his critics say – as Sir Walter Raleigh said of Elizabeth I – that he ‘did it all by halves’. He would have gone further than he needed to go, rather than leaving the impression of being pushed unwillingly into something, and it would provide the launch pad for a General Election.

- In the current atmosphere where politicians are so distrusted, it would act as a guarantee of how a future Conservative Government would be run because it would be beholden to a second party. The promise of a referendum would clearly be of an unbreakable nature in coalition with UKIP, while the tone of the EU renegotiation would be considerably stronger. It would have to be taken more seriously within the EU if a party that wanted to leave were in the Government. It would also be a recognition that all political parties are coalitions covering a range of views.

- Historically, one of the strengths of the Tory Party has been its ability to stretch from Rab Butler to Enoch Powell in so civilised a way that Powell supported Butler’s leadership ambitions. Narrowing the base with a third of potential supporters in another similar party is a sure way to defeat. Generosity, courage and sense pave the path to victory.

- Sadly, I doubt this will be done in time, so I am looking forward to some fair weather in Clacton for a spot of canvassing against a respected erstwhile colleague. It is the district in which my wife grew up, so it could be something of a family outing to join fellow Conservatives opposing someone with whom they agree on most policy issues.[15]

Ruled out by George Osborne

Interviewed on The Andrew Marr Show on 7 September 2014, Chancellor George Osborne declared there would be "no pact with UKIP". Nor would he support the idea that Boris Johnson should stand as the Conservative candidate in the Clacton by-election in an effort to defeat former Tory MP Douglas Carswell who is the UKIP candidate.[16]

Employee on Wikispooks

| Employee | Job | Appointed | End |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gerard Batten | Leader of UK Independence Party | 14 April 2018 | 2 June 2019 |

Party Members

| Politician | Born | Died | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stuart Agnew | 30 August 1949 | A member of the European Parliament | |

| Jonathan Aitken | 30 August 1942 | UK deep politician, Cercle chair, convicted perjurer | |

| Gerard Batten | 27 March 1954 | Former Leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party | |

| Godfrey Bloom | 22 November 1949 | British MEP | |

| John Bufton | 31 August 1962 | A member of the European Parliament | |

| Douglas Carswell | 3 May 1971 | A former Tory who was UKIP's sole representative in Parliament before becoming an Independent MP | |

| Andrew Cavendish | 2 January 1920 | 3 May 2004 | Clermont Set member who attended a meeting of Le Cercle in Oman in 1990 |

| Derek Roland Clark | 10 October 1933 | A member of the European Parliament | |

| Trevor Colman | 27 August 1941 | A member of the European Parliament | |

| Angus Dalgleish | May 1950 | ||

| William Dartmouth | 23 September 1949 | A member of the European Parliament | |

| Richard Everett | |||

| Nigel Farage | 3 April 1964 | Influential campaigner for Brexit in Britain and the European Parliament, elected an MP at his 8th attempt. | |

| Roger Helmer | 25 January 1944 | ||

| Katie Hopkins | 13 February 1975 | UK commentator known for her outspoken views | |

| Christopher Monckton | 14 February 1952 | Journalist, Conservative political advisor, UKIP political candidate | |

| Paul Nuttall | 30 November 1976 | ||

| Malcolm Pearson | 20 July 1942 | ||

| Mark Reckless | 6 December 1970 | A former Conservative MP who defected to UK Independence Party |

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:The Real Reason Theresa May’s Brexit Has Failed | Article | 2 March 2019 | T. J. Coles | So, the choice faced by ordinary British people is between a neoliberal EU supported by millionaires like Kenneth Clarke or an ultra-neoliberal Brexit supported by multimillionaires like Jacob Rees-Mogg. Meanwhile, ordinary working-class people pay the price for these elite games, as usual. |

References

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2004/jun/15/thefarright.uk

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-11700220

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/5338364.stm

- ↑ 'FARAGE, Nigel Paul', Who's Who 2013, A & C Black, 2013; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2012; online edition, November 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ "No Conservative pact with UKIP, says David Cameron"

- ↑ "UKIP 32 points ahead in Clacton"

- ↑ "UKIP conference: Income tax cuts plan unveiled"

- ↑ "Conservative MP Mark Reckless defects to UKIP"

- ↑ https://medium.com/insurge-intelligence/how-big-money-and-big-brother-won-the-british-elections-2e8da57faac4 Insurge Intelligence How Big Money and Big Brother won the British Elections

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-27572878

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-19828606

- ↑ Sam McBride, "McNarry set to join UKIP", Belfast Newsletter, 4 October 2012 (Archived at the Internet Archive)

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-22382098

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2013/may/03/nigel-farage-ukip-change-british-politics}

- ↑ "Why I believe we must give Clegg's job to Nigel Farage... and get in bed with UKIP"

- ↑ "The Andrew Marr Show 07/09/2014"