Sterilization campaign

| |

| Large-scale and well organized sterilization efforts for population control and reduction. |

This article mostly deals with large-scale sterilization efforts for population control and reduction. See also eugenics

Forced sterilization campaigns, also known as compulsory or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to sterilize a specific group of people. Compulsory sterilization removes a person’s capacity to reproduce, usually through surgical procedures, but efforts have also been made more covertly with chemical means by for example "unintentionally" adding a sterilant to drinking water,food sources or vaccines.

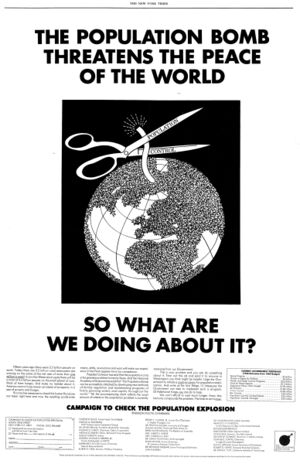

Sterilization and population reduction is an issue that has long been close to the heart of the very richest people in the world.

Most Western countries implemented sterilization programs in the early 20th century, but they were officially discontinued by the 1980s. Such programs were also massively expanded and made more coercive in the Global South starting in the late 1960s, and gained special notoriety during the brutal campaign in India during Indira Gandhi's rule, where people were grabbed off the street and forcibly sterilized under unhygienic conditions. Similar large-scale forced campaigns in South America and Africa have continued unabated. USAID is a large driving force in sterilization campaigns.

Rationalizations for compulsory sterilization have included population control, reduction of the number of poor people, gender discrimination, limiting the spread of HIV, ethnic genocide, and on a geopolitical level (Henry Kissinger), to keep global power structures in place. Later, an environmental rationale was added, where a drastic population reduction became an urgent (but often only left strongly implied) part of the campaign to reduce CO2 emissions.

Early population programs of the twentieth century were marked as part of the eugenics movement, with Nazi Germany's programs providing the most well-known examples of sterilization of "inferior" people, paired with encouraging white Germans who fit the "Aryan race" phenotype to rapidly reproduce. In the 1970s, population control programs focused on the "third world" to help curtail over population of poverty areas that were beginning to economically develop.

Contents

By Country

This describes large scale forced sterilization for population reduction purposes. For smaller campaigns of forced sterilizations for other purposes, see eugenics.

India

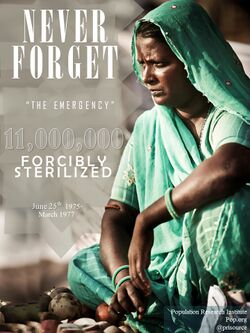

The Emergency in India from 1975 and 1977 resulted from internal and external conflict for the country, and resulted in misuse of power and human rights violations from the government.[1] The state enacted a family planning initiative that began in 1976 in an attempt to lower the exponentially increasing population. This program focused on male citizens and used propaganda and monetary incentives to impoverished citizens to get sterilized.[2] People who agreed to get sterilized would receive land, housing, and money or loans.[3] This program led millions of men to receive vasectomies, and a large prportion of these were coerced. There were reports of officials blocking off villages and dragging men to surgical centers for vasectomies.[4] However, after much protest and opposition, the country switched to targeting women through coercion, withholding welfare or ration card benefits, and bribing women with food and money.[5] This switch was theorized to be based off the principle women are less likely to protest for their own rights.[4] Many deaths occurred as a result of both the male and the female sterilization programs.[4] These deaths were likely attributed to poor sanitation standards and quality standards in the Indian sterilization camps.

Sanjay Gandhi, son of the then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, was largely responsible for what turned out to be a failed program.[1] A strong mistrust against family planning initiatives followed the highly controversial program, the effect of which continues into the 21st century.[6] Sterilization policies are still enforced in India, targeting mostly indigenous and lower class women who are herded into the sterilization camps.[5] Despite these deaths, sterilization is still the highest used method of birth control with 39% of women in India turning to sterilization in 2015.[7]

Brazil

During the 1970s–80s, the U.S. government sponsored family planning campaigns in Brazil, although sterilization was illegal at the time there.[8] Dalsgaard examined sterilization practices in Brazil; analyzing the choices of women who opt for this type of reproductive healthcare in order to prevent future pregnancies and so they can accurately plan their families.[9] While many women nominally choose this form of contraception, there are many societal factors that impact this decision, such as poor economic circumstances, low rates of employment, and Catholic religious mandates that stipulate sterilization as less harmful than abortion.[10]

Colombia

The time period of 1964–1970 started Colombia's population policy development, including the foundation of PROFAMILIA and through the Ministry of Health the family planning program promoted the use of IUDs, the Pill, and sterilization as the main avenues for contraception. By 2005, Colombia had one of the world's highest contraceptive usage rates at 76.9%, with female sterilization being the highest percentage of use at just over 30% (second highest is the IUD at around 12% and the pill around 10%)[11]. In Colombia during the 1980s, sterilization was the second most "popular" choice of pregnancy prevention (after the Pill), and public healthcare organizations and funders (USAID, AVSC, IPPF) supported sterilization as a way to decrease abortions rates. While not directly forced into sterilization, women of lower socio-economic standing had significantly less options to afford family planning care as sterilizations were subsidized.[8]

Guatemala

Guatemala is one country that resisted family planning programs, largely due to lack of governmental support, including civil war strife, and strong opposition from both the Catholic Church and Evangelical Christians until 2000, and as such, has the lowest prevalence of contraceptive usage in Latin America. In the 1980s, the archbishop of the country accused USAID of mass sterilizations of women without consent, but a US commission found the allegations to be false.[12]

Kenya

In Kenya, HIV was considered an ongoing virus, and the governor believed that compulsory sterilizing women infected with HIV could stop the spread of this virus. However, in reality, this brought trouble within the state of Kenya. It was until 2012 sparked outrage, a report titled "Robbed of Choice" explained the experience of 40 women whom women infected with HIV that had been sterilized against their will. There were 5 of the 40 women that filed a lawsuit against the government of Kenya.[13] The reason behind the lawsuit is due to violation of their womanhood and health.[13] The majority of the women sterilized know nothing about being sterilized.[13]

Kenya now has a vaccine called Tetanus Toxoid, and it supposedly is used to cover up sterilization. The doctor or bishop injects HCG in the women, which causes them not to carry a child; in fact, the woman more than likely is going to miscarriage. This vaccine is a smoother way to cover up for compulsory sterilization; However, it is still against the women's will, but they believe that this vaccine helps them rather than reducing their chance of ever carrying a child again.[14]

Peru

In Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) committed a genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of the Programa Nacional de Población, a sterilization program put in place by his administration.[15] During his presidency, Fujimori put in place a program of forced sterilizations against indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras), in the name of a "public health plan", presented on July 28, 1995. The plan was principally financed using funds from USAID (36 million dollars), the Nippon Foundation, and later, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).[16] On September 9, 1995, Fujimori presented a Bill that would revise the "General Law of Population", in order to allow sterilization. Several contraceptive methods were also legalized, all measures that were strongly opposed by the Roman Catholic Church, as well as the Catholic organization Opus Dei. In February 1996, the World Health Organization (WHO) itself congratulated Fujimori on his success in controlling demographic growth.[16]

White House Office of Science and Technology Policy

In the 1977 textbook Ecoscience: Population, Resources, Environment, authors Paul and Anne Ehrlich, and John Holdren discuss a variety of means to address human overpopulation, including the possibility of compulsory sterilization.[17] This book received renewed media attention with the appointment of John Holdren as Assistant to the President for Science and Technology, Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.[18] Several forms of compulsory sterilization are mentioned, including: the proposal for vasectomies for men with three or more children in India in the 1960s,[19] sterilizing women after the birth of their second or third child, birth control implants as a form of removable, long-term sterilization, a licensing system allotting a certain number of children per woman, economic and quota systems of having a certain number of children, and adding a sterilant to drinking water or food sources (the authors are clear that no such sterilant exists nor is one in development).[20] The authors state that most of these policies are not in practice, have not been tried, and most will likely "remain unacceptable to most societies."[20]

Related Quotations

| Page | Quote | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilderberg/2020 | “These [COVID-19] vaccines are unlikely to completely sterilize a population. They're very likely to have an effect which works in a percentage. Say, 60% or 70%.” | John Bell | 2020 |

| Bilderberg/2021 | “These [COVID-19] vaccines are unlikely to completely sterilize a population. They're very likely to have an effect which works in a percentage. Say, 60% or 70%.” | John Bell | 2020 |

| COVID-19/Perpetrators/Bilderberg | “These [COVID-19] vaccines are unlikely to completely sterilize a population. They're very likely to have an effect which works in a percentage. Say, 60% or 70%.” | John Bell | 2020 |

References

- ↑ a b https://web.archive.org/web/20061110074114/http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl1809/18090740.htm

- ↑ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chandigarh/A-generation-of-lost-manhood/articleshow/47824811.cms

- ↑ Relying on Hard and Soft Sells India Pushes Sterilization, New York Times, June 22, 2011.

- ↑ a b c https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-30040790

- ↑ a b https://web.archive.org/web/20190428234457/http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/20444/1/Kalpana%20Wilson%20New%20Formations%202017.pdf

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20060811233229/http://www.malecontraceptives.org/articles/ringheim_article.php

- ↑ https://www.globalhealthnow.org/2018-09/sterilization-standard-choice-india

- ↑ a b Hartmann, Betsy (2016). Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- ↑ Dalsgaard, Anne Line (2004). Matters of Life and Longing: Female Sterilisation in Northeast Brazil. Museum Tusculanum Press.

- ↑ Corrêa, Sonia; Petchesky, Rosalind (1994). Reproductive and Sexual Rights: A Feminist Perspective. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 134–147.

- ↑ Measham and Lopez-Escobar, Anthony, Guillermo (2007). Against the Odds: Colombia's Role in the Family Planning Revolution. World Bank Publisher. pp. 121–135.

- ↑ Santiso-Galvez and Bertrand, Roberto; Jane T. (2007). Guatemala: The Pioneering Days of the Family Planning Movement. World Bank Publications. pp. 137–154.

- ↑ a b c https://www.hhrjournal.org/2015/07/kenya-forced-sterilization-hiv/

- ↑ https://www.americamagazine.org/content/all-things/are-tetanus-vaccines-hiding-contraception-program-kenya-probably-not

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20060630062037/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/2148793.stm

- ↑ a b Stérilisations forcées des Indiennes du Pérou Archived 2014-05-10 at the Wayback Machine., Le Monde diplomatique, May 2004

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20161005193751/http://www.evolutionnews.org/2009/08/the_inconvenient_truth_about_p023831.html

- ↑ https://prospect.org/api/content/8d1d9e25-cd3b-54cf-ba9b-ccab766af4dc/

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/11/14/the-malthusian-roots-of-indias-mass-sterilization-program/

- ↑ a b https://www.foxnews.com/projects/pdf/072109_holdren2.pdf