Difference between revisions of "Bernard Hogan-Howe"

(On 30 June 2015, Patrick Haseldine wrote a second letter to Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe) |

m (Text replacement - "|wikipedia=http://en.wikipedia.org" to "|wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org") |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{person | {{person | ||

|image=Bernard_Hogan-Howe.jpg | |image=Bernard_Hogan-Howe.jpg | ||

| − | |wikipedia= | + | |wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Hogan-Howe |

|constitutes=policeman | |constitutes=policeman | ||

|employment={{job | |employment={{job | ||

Revision as of 04:41, 5 July 2015

(policeman) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Member of | Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies/Fellows | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe QPM (born 25 October 1957) is the present Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (head of London's Metropolitan Police Service).

On 18 July 2011, Home Secretary Theresa May announced Hogan-Howe's temporary appointment as Acting Deputy Commissioner following the resignation of the Commissioner, Sir Paul Stephenson, and the appointment of the incumbent Deputy Commissioner as Acting Commissioner. Hogan-Howe applied for the position of Commissioner himself in August 2011 along with other candidates,[1] and was successful in being selected for the post on 12 September 2011 after appearing before a panel of the Home Secretary and the Mayor of London and receiving the approval of the Chair of the Metropolitan Police Authority, before he was formally appointed by The Queen.[2]

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe was knighted in the 2013 New Year Honours for services to policing.[3]

Contents

Early life and education

Hogan-Howe was born in Sheffield in 1957, the son of Bernard Howe. He attended Hinde House School, a dual primary and secondary school, where he completed his A-levels. He was brought up single-handedly by his mother, whose surname of Hogan he later added by deed poll. After leaving school, he spent four years working as a lab assistant in the National Health Service.[4]

Whilst still with South Yorkshire Police, he was identified as a high-flier and selected to study for an MA degree in Law at Merton College,[5] University of Oxford, which he began at the age of 28.[6] He later went on to gain a Diploma in Applied Criminology from the University of Cambridge and an MBA from the University of Sheffield.[7][8]

Police career

Bernard Hogan-Howe began his police career in 1979 with South Yorkshire Police and rose to be District Commander of the Doncaster West area. In 1997, he transferred over to Merseyside Police as Assistant Chief Constable for Community Affairs, moving onto area operations in 1999. Hogan-Howe then once again transferred this time to the Metropolitan Police Service as Assistant Commissioner for Human Resources, July 2001–2004.[9] He was then appointed Chief Constable of Merseyside Police, 2005-9.[10][11]

Hogan-Howe had called for a "total war on crime" whilst Chief Constable and argued that the Health and Safety case which was successfully brought against the Metropolitan Police after the Jean Charles de Menezes shooting was restrictive of allowing the police to do their work.[12] He had also called for a review of the decision to downgrade cannabis from a class B to a class C drug.[13] He thereafter served as one of Her Majesty's Inspectors of Constabulary, 2009–2011.[14]

Commissioner

On 12 September 2011, it was announced that Bernard Hogan-Howe would become Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis on 26 September. He was briefly Assistant Commissioner responsible for professional standards before formally commencing the role as Commissioner. During that period, a decision was made within the department of professional standards to use the Official Secrets Act to compel The Guardian to reveal its sources regarding the News International phone hacking scandal. The order was swiftly rescinded five days prior to Hogan-Howe's formal term of office.[15] On 16 January 2012, Hogan-Howe gave a talk at the London School of Economics entitled "Total Policing: The Future of Policing in London."[16]

In February 2013, Hogan-Howe was criticised for defending police officers who had, according to an appeal court ruling, used "inhuman and degrading treatment", in breach of the Human Rights Act, when handling an autistic boy in a swimming pool. The criticism was specifically directed against the money spent on the appeal and his refusal to apologise and to improve training police officers for the humane treatment of people with disabilities.[17] In September 2012, Hogan-Howe did ask an independent commission headed by Lord Adebowale to review cases where people with a mental illness died or were harmed after contact with police. The report arrived in May 2013[18] and contained severe criticism; Hogan-Howe responded to the commission's recommendations with a plan for change, announced in June 2014.[19]

The Met

In October 2013, it was announced that the Metropolitan Police Service is to be the subject of The Met, a BBC One documentary five-part series going behind the scenes at Britain's largest police force. Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe said he was "delighted" to work with the BBC "on such an important project":

- "I hope that over the coming months, we can reveal the true scale and complexity of the challenges faced by officers and staff across the service."[20]

On 5 June 2015, Simon Jenkins of The Guardian attended the press viewing of The Met's first episode in the presence of Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe and reported that a BBC official said how “privileged we felt” to be given access to the great man, and hoped the film “will not seem a puff piece for the Met”:

- "I caught a twitch of a smile on Hogan-Howe’s face. 'I don’t want this to seem shroud waving,' he said, and then coolly pointed out he had endured a 20% cut in his budget and now faced the same again."

The Met is not “fly-on-the-wall” television in the style of the pioneering 1982 Thames Valley series, Police, or of more recent glimpses inside submarines, fire brigades, ambulances, Heathrow and Great Ormond Street. These left cameras running “at the front line” and edited the product. The Met is a documentary with interviews, conducted after the police shot Mark Duggan in Tottenham in 2011, and after the subsequent inquest verdict of “lawful killing”. There is no question, the Duggan affair was highly embarrassing for the police, exacerbated by subsequent riots across the capital. It was made worse by the jury’s inexplicable verdict, that Duggan was not holding a gun yet could lawfully be shot.

But that was last year. By then Hogan-Howe had arrived at the Met, and had time to get his ducks in a row. He was clearly determined that the film should reflect his carefully orchestrated handling of the outcome. He also was confident in his co-star, the glamorous and articulate head of the Haringey force, Victor Olisa. Together they played a blinder. The police come over as universally sensitive. There is no whiff of what gave rise to the saga, no sign of the officers present at Duggan’s killing or why they were armed. We get no idea what steps the force made to investigate the incident, or to remedy mistakes. All we get is deep agonising over the aftermath. Meanwhile the Duggan family and the “local community” are mostly portrayed as ranting militants and left-wing extremists. The film ends with the Met in a cloud of glory, successfully policing last year’s Brixton Splash festival.

It really is a puff.

Challenged on whether the film showed the Met as “institutionally racist”, Hogan-Howe wisely declined to answer, except to agree that what matters is “that others think so”.[21]

Bernt Carlsson murder inquiry

On 28 May 2015, veteran Lockerbie campaigner Patrick Haseldine wrote to Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, Metropolitan Police Commissioner, New Scotland Yard, 8-10 Broadway, London SW1H 0BG (Royal Mail Track & Trace Ref. BZ774653397GB):

Dear Sir Bernard,

MURDER OF BERNT CARLSSON, UN COMMISSIONER FOR NAMIBIA

On 7th December 1989 The Guardian published this letter from me:

- "Finger of suspicion"

- "Exactly one year ago, you published my letter suggesting that Mrs Thatcher might have a blind spot as far as South African terrorism is concerned.

- "Fourteen days after publication, Pan Am Flight 103 was blown out of the sky upon Lockerbie. Of the 270 victims, the most prominent person was the Swede Mr Bernt Carlsson – UN Commissioner for Namibia – whose obituary appeared on page 29 of your December 23, 1988 edition.

- "I cannot be the only puzzled observer of this tragedy to wonder why police attention did not immediately focus on a South African connection. The question to be put (probably to Mrs Thatcher) is: given the South African proclivity to using the diplomatic bag for conveying explosives and the likelihood that the bomb was loaded aboard the aircraft at Heathrow (vide David Pallister, The Guardian, November 9, 1989) why has it taken so long for the finger of suspicion to point towards South Africa?

- "Were police inquiries into Lockerbie subject to any political guidance or imperatives?"[22]

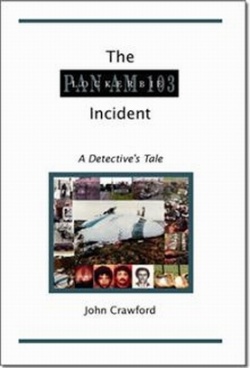

The only “investigation” of Bernt Carlsson’s murder was conducted by Scottish Detective Constable John Crawford whose 2002 book, "The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale", states (on pages 88/89):

- "We even went as far as consulting a very helpful lady librarian in Newcastle who contacted us with information she had on Bernt Carlsson. She provided much of the background on the political moves made by Carlsson on behalf of the United Nations. He had survived a previous attack on an aircraft he had been travelling on in Africa. It is unlikely that he was a target as the political scene in Southern Africa was moving inexorably towards its present state. No matter what happened to Carlsson after he had completed his mission in Namibia the political changes were already well in place and his demise would not have altered anything. This would have made a nonsense of any alleged assassination attempt on him as it would not have achieved anything. I discounted the theory as being almost totally beyond the realms of feasibility. We eventually produced a report on all fifteen (the 'first fifteen' of the interline passengers) to the SIO (Stuart Henderson), each person had their own story and as many antecedents as we could gather. The other teams had also finished their profiles of their group of interline passengers. None of them had found anything which could categorically put any of the interline passengers into any frame as a target, dupe or anything else other than a victim of crime."[23]

There is reason to believe that the following individuals either conspired to murder, or were complicit in targeting, Bernt Carlsson in the Lockerbie bombing of 21 December 1988:

- South African President P. W. Botha (deceased)[24],

- General Magnus Malan (deceased)[25],

- Foreign Minister Pik Botha[26],

- Head of SADF Military Intelligence Major-General Neels van Tonder, who controlled the dirty tricks operation Longreach,

- South African Superspy Craig Williamson[27],

- South African mercenary Lt-Col Eeben Barlow[28],

- Former President of Finland Martti Ahtisaari, who attended the December 1988 negotiations in Brazzaville where the Bernt Carlsson murder plot was hatched,

- Former US Assistant Secretary of State Chester Crocker, whose 'linkage policy' delayed Namibia's independence for 10 years,

- French not-so-secret agent Jean-Yves Ollivier.

I should be grateful if Scotland Yard would now launch a Bernt Carlsson murder inquiry.

Yours sincerely,

Lockerbie crime scene at Heathrow

On 30 June 2015, Patrick Haseldine wrote a second letter to Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe:

Dear Sir Bernard,

My letter of 28th May 2015 asked you to launch a murder inquiry into the targeting of Bernt Carlsson on Pan Am Flight 103, which exploded on 21 December 1988 over Lockerbie in Scotland. In case you are reluctant for Scotland Yard to get involved, I offer the following to justify action by the Met.

According to the National Geographic Channel, the Lockerbie crime scene extended to over 2000 square kilometres and in total some 4 million pieces of wreckage were collected and registered on computer files. The documentary stated:

- ”Early analysis of the wreckage showed signs of an explosion in the front left luggage hold of the plane, indicating that if it was a bomb that had caused the explosion then it had to have been loaded in Frankfurt.”[30]

New analyses by Barry Walker[31] and by Dr Morag Kerr[32] show that the bomb suitcase could not possibly have arrived on the feeder flight Pan Am 103A from Frankfurt. Instead, the two experts have demonstrated that the Lockerbie scene of crime should now be focused on Heathrow airport, where the Pan Am 103 bomb originated.

According to my researches, this is how the bomb suitcase was ingested at Heathrow:

At about 20:00pm (GMT) on 20 December 1988, when flight SA234 took off from Johannesburg airport, full details of the flight's passenger manifest were transmitted to South African Airways office in London. This was the cue for a team of Civil Co-operation Bureau operatives, led by the CCB's London-based director Eeben Barlow, to break through a security door at Terminal 3 of Heathrow airport leading to the Interline Baggage Shed from where flights would be loaded the following day. The CCB team then ingested the primary suitcase (or "bomb bag") through this security door and tagged it for loading on Pan Am Flight 103.[33] For baggage reconciliation purposes, this Samsonite hardshell primary suitcase would replace Nicola Hall's bag (which would be diverted to Pan Am Flight 101). Thus the "bomb bag" and Bernt Carlsson's grey Presikhaaf hardshell suitcase were the first two pieces of luggage placed in the AVE4041 baggage container by loader/driver John Bedford.

Heathrow security guard Ray Manly, who discovered that the padlock had been cut on security door CP2 leading to the Pan Am baggage area, told the Lockerbie appeal court at Camp Zeist in 2002:

- "I believe it would be possible for an unauthorised person to obtain tags for a particular Pan Am flight and then, having broken the CP2 lock, to have introduced a tagged bag into the baggage build up area."

Manly immediately reported the break-in to the police but was not interviewed by Scotland Yard's Anti-Terrorist Squad until 31 January 1989. The officers who interviewed Manly apparently did not pursue the lead or pass on the information.[34] No mention of the Heathrow break-in was made at the 2000-2001 Lockerbie trial of the two Libyans Megrahi and Fhimah.[35]

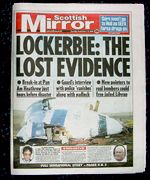

Ray Manly's account of the break-in at Heathrow remained hidden for over twelve years, then suddenly made front page news on 11 September 2001 in the Scottish Mirror ("Lockerbie: The Lost Evidence") and was carried by BBC News that morning at 08:42 GMT ("Key Lockerbie 'evidence' not used").[36] This short-lived Lockerbie story was effectively buried a few hours later when reports of the 9/11 attacks in America began to swamp the media.

Please acknowledge this letter and let me know if you require additional information to proceed with the Bernt Carlsson murder inquiry.

Yours sincerely,

Police Roll of Honour Trust

In November 2013 Bernard Hogan-Howe took up the role of Patron of the national police charity the Police Roll of Honour Trust. He joined Stephen House and Hugh Orde as joint patrons.[37]

Honours and awards

Hogan-Howe's honours and decorations include:

On 14 November 2012, Hogan-Howe was awarded the degree of Doctor of the University (D.Univ) by Sheffield Hallam University.

On 15 July 2013, Hogan-Howe was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Law (LLD) by the University of Sheffield.[38]

References

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "New Year Honours: Kate Bush Heads Arts Field". Sky News. 28 December 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ Sanderson, Frank; Doran, Clare (13 July 2010). "Bernard Hogan-Howe". Liverpool John Moores University. Retrieved 12 September 2011.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "The Sheffield Executive MBA: Case study: Bernard Hogan-Howe". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 18 July 2011.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "MPA appoints two Assistant Commissioners: DAC Tarique Ghaffur and ACC Bernard Hogan-Howe". Metropolitan Police Authority. Retrieved 10 March 2008.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Temporary Chief Constable takes up the baton". Merseyside Police. Retrieved 1 November 2009.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Her Majesty's Inspectors of Constabulary". Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary. Retrieved 1 November 2009.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Total Policing: the future of policing in London". London School of Economics. Retrieved 5 March 2014.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ Trauma of autistic boy shackled by police, by Yvonne Roberts, The Observer, Sunday 17 February 2013

- ↑ Independent Commission on Mental Health and Policing Report

- ↑ The Met’s New Approach To Recognising Mental Health

- ↑ "Metropolitan Police to be subject of BBC documentary"

- ↑ "Sorry, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, but The Met series really is a puff piece"

- ↑ "Finger of suspicion"

- ↑ "The Lockerbie Incident: A Detective's Tale"

- ↑ "From Chequers to Lockerbie"

- ↑ "South Africa’s Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) executed Iran’s revenge attack"

- ↑ "Why the Lockerbie flight booking subterfuge, Mr Botha?"

- ↑ "Craig Williamson: Lockerbie bomber"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: J'accuse...Eeben Barlow"

- ↑ "Scotland Yard to launch Bernt Carlsson murder inquiry"

- ↑ "Lockerbie 20 years on"

- ↑ "Charlatans, Fabricators and Conspiracy Theorists"

- ↑ "Adequately Explained by Stupidity? Lockerbie, Luggage and Lies"

- ↑ "Pan Am 103: South Africa Guilty"

- ↑ "Mirror dossier will clear me" Heathrow expose to help Lockerbie appeal

- ↑ "'Break-in' before Lockerbie bombing"

- ↑ "Key Lockerbie 'evidence' not used"

- ↑ "New Patrons". Retrieved 16 April 2014.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "Summer Graduation Ceremonies 2013". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 13 February 2013.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

External links

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here