Difference between revisions of "Leo Ryan"

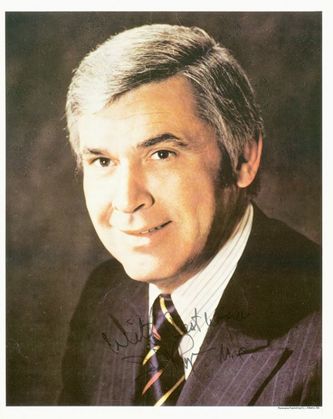

(image) |

m (tidy references) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{person | {{person | ||

| − | |image=Leo Ryan | + | |image=Leo Ryan.jpg |

|image_width=333px | |image_width=333px | ||

| − | |image_caption= | + | |image_caption= |

|constitutes=politician, teacher | |constitutes=politician, teacher | ||

|victim_of=murder | |victim_of=murder | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|political_parties=Democratic | |political_parties=Democratic | ||

|children=5 | |children=5 | ||

| + | |wikiquote=http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Leo_Ryan | ||

|employment={{job | |employment={{job | ||

|title=Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 11th district | |title=Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 11th district | ||

| Line 30: | Line 31: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Ryan was | + | '''Leo Ryan''' was a US congressman famous for vocal criticism of the lack of [[Congressional oversight]] of the [[Central Intelligence Agency]] (CIA), and authored the [[Hughes–Ryan Amendment]], passed in 1974. He was [[murdered]] after travelling to [[Jonestown]] to investigate charges of [[human rights]] violations. |

| − | == | + | ==Prison reform== |

| − | + | “After the Watts Riots of 1965, Assemblyman Ryan went to the area and took a job as a substitute school teacher to investigate and document conditions in the area. In 1970, using a pseudonym, Ryan had himself arrested, detained, and strip searched to investigate conditions in the California prison system. He stayed as an inmate for ten days in the Folsom Prison, while presiding as chairman on the Assembly committee that oversaw prison reform.”<ref name=gr>http://www.greanvillepost.com/2016/10/03/encyclopedia-of-domestic-assassinations/#Ryan</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Jonestown== | |

| + | In 1978, reports regarding widespread abuse and [[human rights]] violations in [[Jonestown]] among the [[Peoples Temple]], led by [[cult]] leader [[Jim Jones]], began to filter out of the organization's [[Guyana]] enclaves. Ryan was friends with the father of former Temple Member Bob Houston, whose mutilated body was found near train tracks on October 5, 1976, three days after a taped telephone conversation with Houston's ex-wife in which leaving the Temple was discussed.<ref name="reiterman299">{{Harvnb|Reiterman|Jacobs|1982|pp=299–300, 457}}</ref> Ryan's interest was further aroused by the custody battle between the leader of a "Concerned Relatives" group, [[Timothy Stoen]], and Jones following a Congressional "white paper" written by Stoen detailing the events.<ref name="hall227">Hall, John R. (1987). Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-124-3. page 227</ref><ref name="reiterman458">{{Harvnb|Reiterman|Jacobs|1982|p=458}}</ref> Ryan was one of 91 Congressmen to write Guyanese Prime Minister [[Forbes Burnham]] on Stoen's behalf.<ref name="reiterman299" /><ref name="hall227" /> | ||

| − | He was shot to death along with others by a member of [[Jim Jones]]' people's temple aboard a small plane due to depart. | + | Later, after reading an article in the ''[[San Francisco Examiner]]'', Ryan declared his intention to go to [[Jonestown]], an [[agricultural commune]] in [[Guyana]] where Jim Jones and roughly 1,000 Temple members resided. Ryan's choice was also influenced both by the Concerned Relatives group, which consisted primarily of Californians, as were most Temple members, and by his own characteristic distaste for social injustice.<ref>McConnell, Malcolm (1984). Stepping Over: personal encounters with young extremists. Reader's Digest Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-88349-166-4.</ref> According to the ''[[San Francisco Chronicle]]'', while investigating the events, the [[United States Department of State]] "repeatedly stonewalled Ryan's attempts to find out what was going on in Jonestown", and told him that "everything was fine".<ref name="simon1998">"A Trip Into The Heart Of Darkness: Always larger than life, Leo Ryan courted danger." San Francisco Chronicle pages=A17, date=December 10, 1998</ref> The State Department characterized possible action by the United States government in Guyana against Jonestown as creating a potential "legal controversy", but Ryan at least partially rejected this viewpoint.<ref>Dawson, Lorne L. (2003). Cults and New Religious Movements: A Reader. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 186, 200, 205.</ref> In a later article in ''The Chronicle'', Ryan was described as having "bucked the local Democratic establishment and the [[Jimmy Carter]] administration's State Department" in order to prepare for his own investigation. |

| + | [[image:Leo Ryan's plane.jpg|left|380px|thumbnail|The Cessna on which Leo Ryan was shot just before he could escape.]] | ||

| + | ==Murder== | ||

| + | He was shot to death along with others by a member of [[Jim Jones]]' people's temple aboard a small plane due to depart. "Leo Ryan’s murder is seen by many as being much more sinister than the hysterical behavior of a madman. Leo Ryan had been a strong critic of the CIA and was the author of the Hughes-Ryan Amendment, which, if passed, would have required that the CIA report to Congress on all of its covert operations before they commenced. Soon after Ryan’s death, the Hughes-Ryan Amendment was quashed in Congress. The question conspiracy theorists ask is whether Ryan was killed in order to reach this objective and the massacre at ‘Jonestown’ merely a smoke screen to distract attention away from Ryan’s murder."<ref name=gr/> | ||

{{SMWDocs}} | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 11:32, 8 August 2021

(politician, teacher) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1925-05-05 Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | 1978-11-18 (Age 53) Port Kaituma, Guyana |

| Alma mater | Creighton University |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Children | 5 |

| Victim of | murder |

| Party | Democratic |

Leo Ryan was a US congressman famous for vocal criticism of the lack of Congressional oversight of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and authored the Hughes–Ryan Amendment, passed in 1974. He was murdered after travelling to Jonestown to investigate charges of human rights violations.

Prison reform

“After the Watts Riots of 1965, Assemblyman Ryan went to the area and took a job as a substitute school teacher to investigate and document conditions in the area. In 1970, using a pseudonym, Ryan had himself arrested, detained, and strip searched to investigate conditions in the California prison system. He stayed as an inmate for ten days in the Folsom Prison, while presiding as chairman on the Assembly committee that oversaw prison reform.”[1]

Jonestown

In 1978, reports regarding widespread abuse and human rights violations in Jonestown among the Peoples Temple, led by cult leader Jim Jones, began to filter out of the organization's Guyana enclaves. Ryan was friends with the father of former Temple Member Bob Houston, whose mutilated body was found near train tracks on October 5, 1976, three days after a taped telephone conversation with Houston's ex-wife in which leaving the Temple was discussed.[2] Ryan's interest was further aroused by the custody battle between the leader of a "Concerned Relatives" group, Timothy Stoen, and Jones following a Congressional "white paper" written by Stoen detailing the events.[3][4] Ryan was one of 91 Congressmen to write Guyanese Prime Minister Forbes Burnham on Stoen's behalf.[2][3]

Later, after reading an article in the San Francisco Examiner, Ryan declared his intention to go to Jonestown, an agricultural commune in Guyana where Jim Jones and roughly 1,000 Temple members resided. Ryan's choice was also influenced both by the Concerned Relatives group, which consisted primarily of Californians, as were most Temple members, and by his own characteristic distaste for social injustice.[5] According to the San Francisco Chronicle, while investigating the events, the United States Department of State "repeatedly stonewalled Ryan's attempts to find out what was going on in Jonestown", and told him that "everything was fine".[6] The State Department characterized possible action by the United States government in Guyana against Jonestown as creating a potential "legal controversy", but Ryan at least partially rejected this viewpoint.[7] In a later article in The Chronicle, Ryan was described as having "bucked the local Democratic establishment and the Jimmy Carter administration's State Department" in order to prepare for his own investigation.

Murder

He was shot to death along with others by a member of Jim Jones' people's temple aboard a small plane due to depart. "Leo Ryan’s murder is seen by many as being much more sinister than the hysterical behavior of a madman. Leo Ryan had been a strong critic of the CIA and was the author of the Hughes-Ryan Amendment, which, if passed, would have required that the CIA report to Congress on all of its covert operations before they commenced. Soon after Ryan’s death, the Hughes-Ryan Amendment was quashed in Congress. The question conspiracy theorists ask is whether Ryan was killed in order to reach this objective and the massacre at ‘Jonestown’ merely a smoke screen to distract attention away from Ryan’s murder."[1]

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:Jonestown.pdf | essay | 1985 | John Judge | A seminal work on Jim Jones, leader of The People's Temple and the massacre at Johnstown Guyana. |

References

- ↑ a b http://www.greanvillepost.com/2016/10/03/encyclopedia-of-domestic-assassinations/#Ryan

- ↑ a b Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 299–300, 457

- ↑ a b Hall, John R. (1987). Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-124-3. page 227

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 458

- ↑ McConnell, Malcolm (1984). Stepping Over: personal encounters with young extremists. Reader's Digest Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-88349-166-4.

- ↑ "A Trip Into The Heart Of Darkness: Always larger than life, Leo Ryan courted danger." San Francisco Chronicle pages=A17, date=December 10, 1998

- ↑ Dawson, Lorne L. (2003). Cults and New Religious Movements: A Reader. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 186, 200, 205.