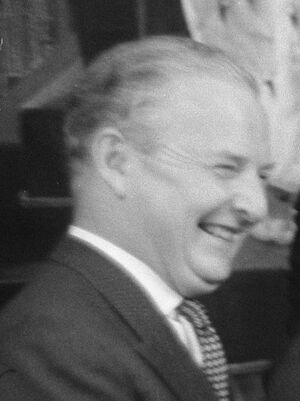

Selwyn Lloyd

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 1904-07-28 West Kirby, Wirral, Cheshire, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 May 1978) (Age 73) Oxfordshire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | British | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | • Fettes College • Magdalene College (Cambridge) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Methodist | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Conservative | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs during the Suez Crisis

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Selwyn Brooke Lloyd known for most of his career as Selwyn Lloyd, was a British politician.

Contents

Early years

Lloyd grew up near Liverpool. After being an active Liberal as a young man in the 1920s, he was sympathetic to Oswald Mosley's New Party in 1930–31, and was disappointed that it made so little headway. The following decade he practised as a barrister and served on Hoylake Urban District Council, by which time he had become a Conservative Party sympathiser, but did not formally join the Conservative Party until he was selected as a Parliamentary candidate in 1945. During the Second World War he rose to be Deputy Chief of Staff of Second Army, playing an important role in planning sea transport to the Normandy beachhead and reaching the acting rank of brigadier. Lloyd was also sent by Dempsey to identify Heinrich Himmler's body after his alleged suicide.[1]

Elected to Parliament in 1945, he held ministerial office from 1951, was Minister of Supply from 1954, then Minister of Defence 7 April 1955 – 20 December 1955, eventually rising to be Foreign Secretary under Prime Minister Anthony Eden from December 1955. He continued as Foreign Secretary under the premiership of Harold Macmillan until July 1960, when he was moved to the job of Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Suez Crisis

Despite his reluctance, he was one of the key players in the Suez Canal Crisis. Following the nationalization of the canal by Gamal Abdel Nasser on July 26, 1956, he was one of the cabinet members opposed to the use of force and actively participated in the first (16-23 August) and second (19-21 September) London conferences aimed at finding a diplomatic solution to the crisis. But faced with Anthony Eden's desire to use force, he was one of the negotiators of the secret Protocols of Sèvres sealing the alliance between the United Kingdom, France and Israel.

Following the Israeli invasion of Egypt on October 29 and the Franco-British intervention that followed, he chose, unlike his colleague Anthony Nutting, to remain in government despite his opposition to the project. In the weeks that followed, he endeavored to limit the diplomatic damage to London by preserving a role for the British in the management of the canal. His failure led him to submit his resignation on November 28, but it was refused. He therefore had the responsibility of assuming, in place of Anthony Eden, ill and recovering in Jamaica, the political storm which followed the failure of Suez intervention.

When Anthony Eden was replaced by Harold Macmillan as Prime Minister on January 14, 1957, Selwyn Lloyd was appointed to the post of Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. He played a fundamental role in the resolution of the Cypriot crisis which led to the independence of the island on August 16, 1960. On July 27, 1960, he was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer and his decision of July 1961 freezing salaries in order to to fight inflation made him strongly unpopular. On July 13, 1962, in what the English have dubbed "the night of the long knives", Harold Macmillan sacked seven ministers, including Selwyn Lloyd, in the hope that his government might regain its popularity.

He returned to office under Prime Minister Alec Douglas-Home as Leader of the House of Commons (1963–64), and was elected Speaker of the House of Commons from 1971 until his retirement in 1976.

Personal life

Lloyd was born on 28 July 1904 at Red Bank in West Kirby, Cheshire.[2] His father, John Wesley Lloyd (1865–1954), was a dental surgeon of Welsh descent and a Methodist lay preacher; his mother, Mary Rachel Warhurst (1872–1959), was distantly related to Field Marshal Sir John French. He had three sisters.

He was educated at the Leas School. He was particularly interested in military history as a boy, a fact to which he later attributed his successful military career. He won a scholarship to Fettes College in 1918. At Fettes, he became embroiled in a homosexual scandal as a junior boy. He was nicknamed "Jezebel" after his initials (JSBL), but was deemed to be the innocent party, and escaped punishment whilst three older boys were expelled.[3][4]

Lloyd was respected for his cool and shrewd judgement. In public he was "a stiff-necked, prickly, rather off-putting figure"[5] and even in private, after his dismissal from the Exchequer "he had a ruffled, sad look as though bad news had only just reached him."[6] However, he could sometimes be a much more gregarious and charismatic man in private than his reserved public image would have suggested.

Sir Ferdinand Mount, 3rd Bt., wrote that he possessed "an exact appreciation of himself". "He was proud of the things he was patronised for" (being called "the Little Attorney" by Macmillan, or "Mr Hoylake UDC" by Bernard Levin). In politics, he was loyal to his (self-proclaimed) social superiors who often did not display loyalty in return.[7]

Lloyd married his secretary Elizabeth Marshall, known as Bae, daughter of Roland Marshall of West Kirby, a family friend.[8] Lloyd, who still lived with his parents when in the Wirral, and who had never had a serious girlfriend, was uneasy with women.[9] He wrote to his parents (November 1950) that "the fatal announcement" of their engagement had been made and that he felt like somebody shivering before getting into a cold bath. Lloyd was 46 whilst Bae, a solicitor by profession, was born in 1928, making her 24 years his junior. At the reception somebody told him that he had a beautiful bride, and he responded that he had a beautiful wedding cake too. Selwyn and Bae had a daughter, Joanna, but divorced in 1957.[10][11] At the time of Suez Bae had been in a bad car crash with her lover, whom she later married.[12] Lloyd was awarded custody of his daughter. He remained on friendly terms with his wife after his divorce,[13] but seldom spoke of her to others, so much so that Ferdinand Mount records that he had no idea how her name was pronounced. Rab Butler quipped that Selwyn's wife had left him "because he got into bed with his sweater on".[14]

Homosexuality

After his divorce, rumour sometimes circulated that Lloyd had homosexual inclinations. He entertained young servicemen at Chequers.[15] Sir Ferdinand Mount writes that he was clearly attracted to the young Jonathan Aitken (his godson, who also worked for him in the early 1960s) but showed no interest in Diana Leishman, an attractive young woman who also worked for him.[16] Michael Bloch writes that he was "infatuated with" Aitken who "had some difficulty parrying his advances" and with the young Peter Walker. The actor Anthony Booth (in his book "Stroll On" (1989)) claimed that he had been accosted on the Mall by a clearly drunk Selwyn Lloyd, who made a pass at him under the pretext of asking for a light for his cigarette, a recognised courtship ritual among gay men at the time, inviting him back to Admiralty House (which was Lloyd's official residence in 1963-4). Ferdinand Mount comments that such behaviour as alleged by Booth would have been out of character, but adds carefully that "It is not clear whether [Lloyd] was ever gay in the active sense".[17][18] Charles Williams writes that Lloyd "had a dubious private life" and that his "private life was the subject of much gossip" but offers no further details.[19]

Further reading

- Bloch, Michael (2015). Closet Queens: Some 20th Century British Politicians. London: Little, Brown Ltd. ISBN 978-1-408-70412-7.

- Clark, Peter (1999) [1992]. A Question of Leadership. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-140-28403-4.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (2013). An English Affair: Sex, Class and Power in the Age of Profumo. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-007-43585-2.

- Dell, Edmund (1997). The Chancellors: A History of the Chancellors of the Exchequer, 1945-90. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-006-38418-2. covers his term as Chancellor.

- Jago, Michael (2015). Rab Butler: The Best Prime Minister We Never Had?. London: Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-849-54920-2.

- Matthew (editor), Colin (2004). Dictionary of National Biography. 34. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-61411-1., essay on Selwyn Lloyd written by D.R.Thorpe

- Mount, Ferdinand (2009). Cold Cream: My Early Life and Other Mistakes (paperback ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-747-59647-9. (Mount worked for Lloyd as a young man in the early 1960s)

- Sandbrook, Dominic (2005). Never Had It So Good. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-349-11530-6.

- Shepherd, Robert (1994). Iain Macleod. Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-091-78567-3.

- Thorpe, D. R. (1989). Selwyn Lloyd. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd. ISBN 978-0-224-02828-8.

- Thorpe, D. R. (2010). Supermac: The Life of Harold Macmillan (Kindle ed.). London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-1-844-13541-7.

- Williams, Charles (2010). Harold Macmillan (paperback ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-753-82702-4.Watry, David M. Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014. ISBN 9780807157183

References

- ↑ Matthew (editor), Colin (2004). Dictionary of National Biography, p. 158.

- ↑ Matthew 2004, p. 157.

- ↑ Bloch 2015, pp. 202–4.

- ↑ Thorpe 1989, p. 17.

- ↑ Mount 2009, p. 245.

- ↑ Mount 2009, p. 246.

- ↑ Mount 2009, pp. 248–9.

- ↑ Thorpe 1989, p. 148.

- ↑ Mount 2009, pp. 246–8.

- ↑ http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31371

- ↑ The Times (Thursday, 18 May 1978), p. 21.

- ↑ Mount 2009, p. 250.

- ↑ Thorpe 1989, p. 206.

- ↑ Sandford 2005, p. 78.

- ↑ Bloch 2015, pp. 202–4.

- ↑ Mount 2009, p. 247.

- ↑ Bloch 2015, pp. 202–4.

- ↑ Mount 2009, p. 248.

- ↑ Williams 2010, pp. 279, 325.