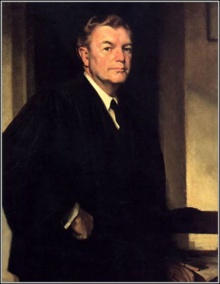

Robert H. Jackson

Robert H. Jackson, c. 1945 | |

| Born | Robert Houghwout Jackson 1892-02-13 Spring Creek Township, Warren County, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | 1954-10-09 (Age 62) Washington DC, USA |

| Alma mater | Albany Law School |

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American attorney and judge who was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He had previously beenUnited States Solicitor General and United States Attorney General, and is the only person to have held all three of those offices.

Jackson was also notable for his work as Chief United States Prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals following World War II.

"If certain acts and violations of treaties are crimes, they are crimes whether the United States does them or whether Germany does them. We are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us.” - Justice Robert H. Jackson, Chief Prosecutor, Nuremberg War Crimes Trials[1]

Contents

Early Career

Jackson decided on a legal career; since attendance at college or law school was not a requirement if a student learned under the tutelage of an established attorney, at age 18 he began to study law with the Jamestown, New York firm in which his uncle, Frank Mott, was a partner. His uncle soon introduced him to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was then serving as a member of the New York State Senate. Jackson attended Albany Law School of Union University from 1911 to 1912.

After completing the year at Albany Law School, Jackson returned to Jamestown to complete his studies.[2] He passed the New York bar examination in 1913, and then joined a law practice in Jamestown. In 1917, Jackson was recruited to work for Penney, Killeen & Nye, a leading Buffalo firm, primarily defending the International Railway Company in trials and appeals.

Over the next 15 years, he built a successful practice, and became a leading lawyer in New York State; he also enhanced his reputation nationally, through leadership roles with bar associations and other legal organizations. In 1930, Jackson was elected to membership in the American Law Institute; in 1933, he was elected Chairman of the American Bar Association's Conference of Bar Association Delegates (a predecessor to today's ABA House of Delegates).[3]

Jackson became active in politics as a Democrat; in 1916, he spearheaded Jamestown's local Wilson for President organization.[4] In the years during and after World War I, he was a member of the New York State Democratic Committee.[5] He also continued his association with Roosevelt; when Roosevelt served as Governor of New York from 1929 to 1933, he appointed Jackson to a commission which reviewed the state judicial system and proposed reforms.[6] Jackson also turned down Roosevelt's offer to appoint him to the New York Public Service Commission, because he preferred to remain in private practice.

Federal appointments, 1934–1941

In 1932, Jackson was active in Franklin Roosevelt's Presidential campaign as Chairman of an organization called Democratic Lawyers for Roosevelt.[7] (Another Robert H. Jackson was also active in the Roosevelt campaign.[8] That Jackson (1880-1973) was Secretary of the Democratic National Committee, and was a resident of New Hampshire.)

In 1934, Jackson agreed to join the Roosevelt administration; he was initially as Assistant General Counsel of the U.S. Treasury Department's Bureau of Internal Revenue (today's Internal Revenue Service), where he was in charge of 300 lawyers who tried cases before the Board of Tax Appeals.[9] In 1936, Jackson became Assistant Attorney General, heading the Tax Division of the Department of Justice, and in 1937, he became Assistant Attorney General, heading the Antitrust Division.[10]

Jackson was a supporter of the New Deal, litigating against corporations and utilities holding companies.[11] He participated in the 1934 prosecution of Samuel Insull, the 1935 income tax case against Andrew Mellon,[12] and the 1937 anti-trust case against Alcoa, in which the Mellon family held an important interest.[13]. Some allege the prosecutions was a revenge act from FDR.

Jackson was then appointed to be the 57th Attorney General of the United States by Roosevelt, on January 4, 1940, replacing Frank Murphy, whom Roosevelt had appointed to the Supreme Court. As Attorney General, Jackson supported a bill introduced by Sam Hobbs, that would have legalized wiretapping by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), or any other government agency, if it was suspected that a felony was occurring.[14] The bill was opposed by Federal Communications Commission (FCC) chairman James Lawrence Fly, and it did not pass.[15]

While Jackson was Attorney General, he helped President Roosevelt organize the Lend-Lease agreement, which allowed the United States to supply materials to help with the war effort to the other Allied forces, before formally entering World War II.

Supreme Court

When Harlan Fiske Stone replaced the retiring Charles Evans Hughes as Chief Justice in 1941, Roosevelt appointed Jackson to the resulting vacant Associate's seat. The nomination was sent to Congress on June 12, 1941, and Jackson was confirmed by the United States Senate on July 7, 1941, receiving his commission on July 11, 1941.

International Military Tribunal, 1945–1946

In 1945, President Harry S. Truman appointed Jackson (who took a leave of absence from the Supreme Court), as U.S. Chief of Counsel for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals. He helped draft the London Charter of the International Military Tribunal, which created the legal basis for the Nuremberg Trials. He then served in Nuremberg, Germany, as United States Chief Prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal.[16] Jackson pursued his prosecutorial role with a great deal of vigor. His opening and closing arguments before the Nuremberg court were widely celebrated. In the words of defendant Albert Speer, the Nazi Minister of Armaments and War Production,

The trial began with the grand, devastating opening address by the Chief American Prosecutor, Justice Robert H. Jackson. But I took comfort from one sentence in it which accused the defendants of guilt for the regime's crimes, but not the German people.[17]

However, some believe that his cross-examination skills were generally weak, and it was British prosecutor David Maxwell-Fyfe who got the better of Hermann Göring in cross-examination, rather than Jackson, who was rebuked by the Tribunal for losing his temper and being repeatedly baited by Göring during the proceedings.[18]

Event Participated in

| Event | Start | End | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDR/Presidency | 4 March 1933 | 12 April 1945 | The administration of president Franklin D. Roosevelt 1933-1945 |

References

- ↑ http://dhalpin.infoaction.org.uk/42-articles/the-established-church-of-england/193-let-the-crucifixion-of-the-palestinian-continue

- ↑ History of Chautauqua County New York and its People.

- ↑ The Nuremberg Trials: International Criminal Law Since 1945.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=8fxEZbKQqWcC&pg=PA224

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=CXJIAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA47

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=svxzgTPwG1wC&pg=PA75

- ↑ https://www.newspapers.com/image/114103876/ |work=Poughkeepsie Eagle-News

- ↑ =https://archive.org/details/thatmaninsidersp00jack

- ↑ http://supremecourthistory.org/timeline_robertjackson1941-1945.html

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=I_f6Oo9H3YsC&pg=PA232

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/forgottenmannewh00shla_259

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=mj3VmJ38tHIC&q=mellon+jackson+%22income+tax%22&pg=PA569

- ↑ http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,848675,00.html

- ↑ U.S. House Subcommittee no. 1 of the Committee on the Judiciary, To Authorize Wire Tapping. Hearings on H.R. 2266, H.R. 3099, 77th Cong., 1st sess., 1941, 1, 257

- ↑ Childs, Marquis W. (March 18, 1941). "House Committee Approval Likely on Wire-Tapping". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. p. 3. Section A.

- ↑ The Nuremberg Roles of Justice Robert H. Jackson: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1147&context=law_globalstudies

- ↑ Speer, Albert, Inside the Third Reich, page 513, Macmillan, New York 1970 (1982 reprint by Bonanza)

- ↑ Ann Tusa and John Tusa, The Nuremberg Trial" (London, Macmillan, 1983), pp 269-293.