Document:Depopulation of the Chagos Islands 1965-73

Subjects: Chagos Islands, Chagos Archipelago/Depopulation

Source: Mark Curtis' Website (Link)

An edited extract from Web of Deceit: Britain’s Real Role in the World ISBN 0099448394

See Also

- Falklands and Chagos - A Tale of Two Islands - A comparison of the treatment of similar sized populations of British subjects on two remote Island dependencies

★ Start a Discussion about this document

The depopulation of the Chagos Islands, 1965-73

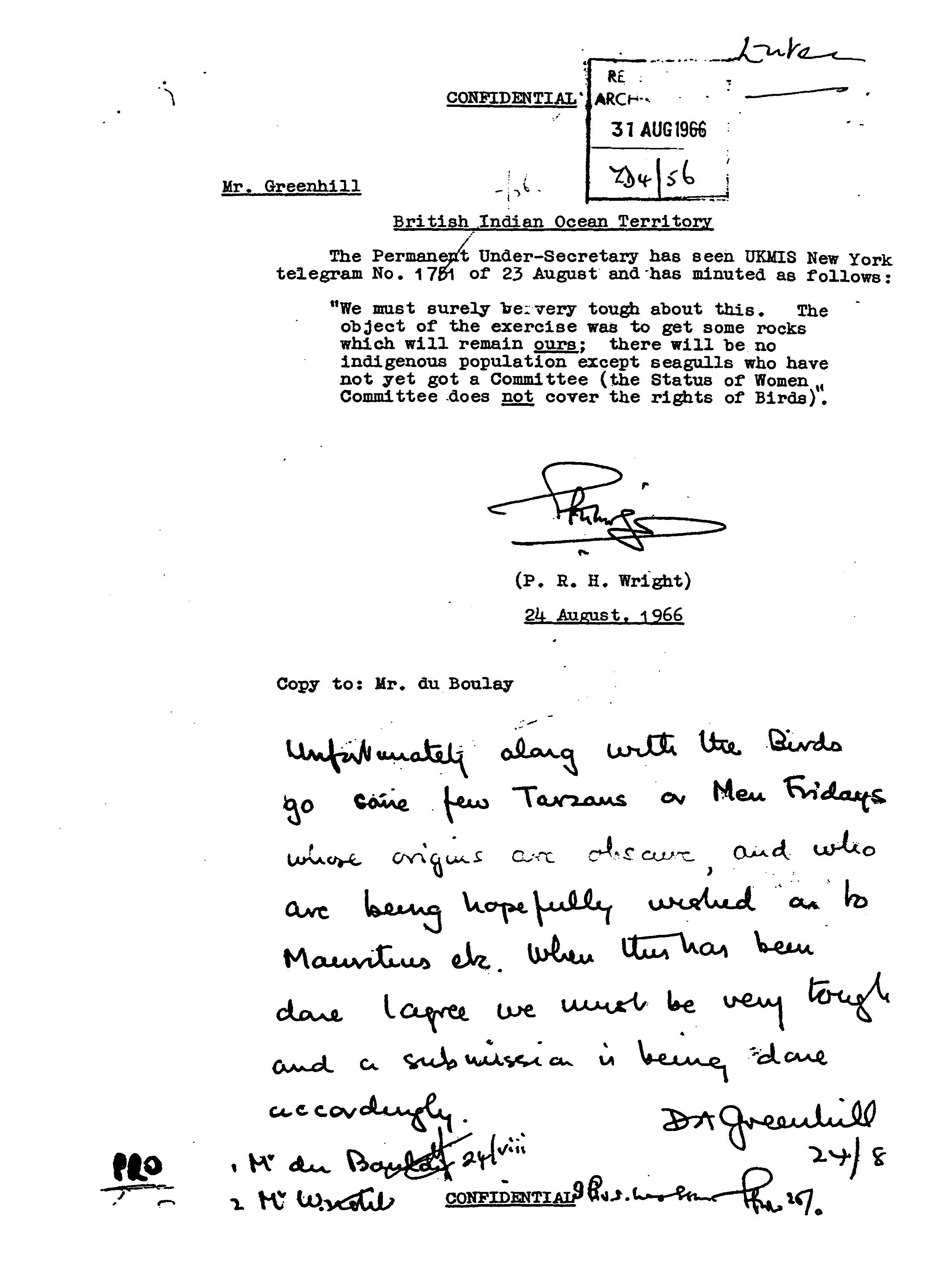

“The object of the exercise was to get some rocks which will remain ours” (Foreign Office, 1966)[1]

During the decolonisation process in the 1960s Britain created a new colony – the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). This included the Chagos island group which was detached from Mauritius, and other islands detached from the Seychelles. Mauritius had been granted independence by Britain in 1965 on the barely concealed condition that London be allowed to buy the Chagos island group from it – Britain gave Mauritius £3m. “The object of the exercise was to get some rocks which will remain ours”, the Permanent Under Secretary at the Foreign Office, its chief civil servant, said in a secret file of 1966. The Colonial Office similarly noted that the “prime object of BIOT exercise was that the islands… hived off into the new territory should be under the greatest possible degree of UK control [sic]“.

In December 1966 the Wilson government signed a military agreement with the US leasing the BIOT to it for military purposes for fifty years with the option of a further twenty years. Britain thus ignored UN Resolution 2066XX passed by the General Assembly in December 1965 which called on the UK “to take no action which would dismember the territory of Mauritius and to violate its territorial integrity”. Higher matters were at stake: Diego Garcia, the largest island in the Chagos group, was well situated as a military base. Britain allowed the US to build up Diego Garcia as a nuclear base and as the launch pad for intervention in the Middle East, notably in Afghanistan and Iraq. Diego Garcia’s role “has become increasingly important over the last decade in supporting peace and stability in the region”, a Foreign Office spokesman managed to say with a straight face in 1997.

To militarise Diego Garcia, Britain removed the 1,500 indigenous inhabitants of the Chagos islands – “the compulsory and unlawful removal of a small an unique population, Citizens of the UK and Colonies, from islands that had formed their home, and also the home of the parents, grand-parents and very possibly earlier ancestors”, as the Chagossians’ defence lawyers put it. The islanders were to be “evacuated as and when defence interests require this”, against which there should be “no insurmountable obstacle”, the Foreign Office had noted.

The Chagossians were removed from Diego Garcia by 1971 and from the outlying islands of Salomen and Peros Banhos by 1973. The secret files show that the US wanted Diego Garcia to be cleared “to reduce to a minimum the possibilities of trouble between their forces and any ‘natives’”. This removal of the population “was made virtually a condition of the agreement when we negotiated it in 1965?, in the words of one British official. Foreign Office officials recognised that they were open to “charges of dishonesty” and needed to “minimise adverse reaction” to US plans to establish the base. In secret, they referred to plans to “cook the books” and “old fashioned” concerns about “whopping fibs”.

The Chagossians were described by a Foreign Office official in a secret file: “unfortunately along with birds go some few Tarzans or man Fridays whose origins are obscure”. Another official wrote, referring to a UN body on women’s issues: “There will be no indigenous population except seagulls who have not yet got a committee (the status of women committee does not cover the rights of birds)”. According to the Foreign Office, “these people have little aptitude for anything other than growing coconuts”. The Governor of the Seychelles noted that it was “important to remember what type of people” the islanders are: “extremely unsophisticated, illiterate, untrainable and unsuitable for any work other than the simplest labour tasks of a copra plantation”.

Contrary to the racist indifference of British planners, the Chagossians had constructed a well-functioning society on the islands by the mid-1960s. They earned their living by fishing, and rearing their own vegetables and poultry. Copra industry had been developed. The society was matriarchal, with Illois women having the major say over the bringing up of the children. The main religion was Roman Catholic and by the first world war the Illois had developed a distinct culture and identity together with a specific variation of the Creole language. There was a small hospital and a school. Life on the Chagos islands was certainly hard, but also settled. By the 1960s the community was enjoying a period of prosperity with the copra industry thriving as never before. The islanders were also exporting guano, used for phosphate, and there was talk of developing the tourist industry.

Then British foreign policy intervened. One of the victims recalled: “We were assembled in front of the manager’s house and informed that we could no longer stay on the island because the Americans were coming for good. We didn’t want to go. We were born here. So were our fathers and forefathers who were buried in that land”.

Britain expelled the islanders to Mauritius without any workable resettlement scheme, gave them a tiny amount of compensation and later offered more on condition that the islanders renounced their rights ever to return home. Most were given little time to pack their possessions and some were allowed to take with them only a minimum of personal belongings packed into a small crate. They were also deceived into believing what awaited them. Olivier Bancoult said that the islanders “had been told they would have a house, a portion of land, animals and a sum of money, but when they arrived [in Mauritius] nothing had been done”. Britain also deliberately closed down the copra plantations to increase the pressure to leave. A Foreign Office note from 1972 states that “when BIOT formed, decided as a matter of policy not to put any new investment into plantations” [sic], but to let them run down. And the colonial authorities even cut off food imports to the Chagos islands; it appears that after 1968 food ships did not sail to the islands.

Not all the islanders were physically expelled. Some, after visiting Mauritius, were simply – and suddenly – told they were not allowed back, meaning they were stranded, turned into exiles overnight. Many of the islanders later testified to having been tricked into leaving Diego Garcia by being offered a free trip.

Most of the islanders ended up living in the slums of the Mauritian capital, Port Louis, in gross poverty; many were housed in shacks, most of them lacked enough food, and some died of starvation and disease. Many committed suicide. A report commissioned by the Mauritian government in the early 1980s found that only 65 of the 94 Illois householders were owners of land and houses; and 40 per cent of adults had no job. Today, most Chagossians continue to live in poverty, with unemployment especially high.

British officials were completely aware of the poverty and hardships likely to be faced by those they had removed from their homeland. When some of the last of the Chagossians were removed in 1973 and arrived in Mauritius, the High Commission noted that the Chagossians at first refused to disembark, having “nowhere to go, no money, no employment”. Britain offered a miniscule £650,000 in compensation, which only arrived in 1978, too late to offset the hardship of the islanders. The Foreign Office stated in a secret file that “we must be satisfied that we could not discharge our obligation… more cheaply”. As the Chagossians’ defence lawyers argue, “the UK government knew at the time that the sum given [in compensation] would in no way be adequate for resettlement.”

Ever since their removal, the islanders have campaigned for proper compensation and for the right to return. In 1975, for example, the islanders presented a petition to the British High Commission in Mauritius. It said: “We, the inhabitants of the Chagos islands – Diego Garcia, Peros Banhos and Salomen – have been uprooted from these islands because the Mauritius government sold the islands to the British government to build a base. Our ancestors were slaves on those islands but we know that we are the heirs of those islands. Although we were poor we were not dying of hunger. We were living free… Here in Mauritius… we, being mini-slaves, don’t get anybody to help us. We are at a loss not knowing what to do.”

The response of the British was to tell the islanders to address their petition to the Mauritian government. The British High Commission in Mauritius responded to a petition in 1974 saying that “High Commission cannot intervene between yourselves as Mauritians and government of Mauritius, who assumed responsibility for your resettlement”. This, as the British government well knew, was a complete lie, as many of the Chagossians could claim nationality “of the UK and the colonies” (see below). In 1981, a group of Illois women went on hunger strike for 21 days and several hundred women demonstrated in vain in front of the British High Commission in Mauritius.

The Whitehall conspiracy

The British response was: after removing the islanders from their home, to remove them from history, in the manner of Winston Smith. In 1972 the US Defence Department could tell Congress that “the islands are virtually uninhabited and the erection of the base would thus cause no indigenous political problems”. In December 1974 a joint UK-US memorandum in question-and-answer form asked “Is there any native population on the islands?”; its reply was “no”. A British Ministry of Defence spokesman denied this was a deliberate misrepresentation of the situation by saying “there is nothing in our files about inhabitants or about an evacuation”, thus confirming that the Chagossians were official Unpeople.

Formerly secret planning documents revealed in the court case show the lengths to which Labour and Conservative governments have gone to conceal the truth. Whitehall officials’ strategy is revealed to have been “to present to the outside world a scenario in which there were no permanent inhabitants on the archipelago”. This was essential “because to recognise that there are permanent inhabitants will imply that there is a population whose democratic rights will have to be safeguarded”. One official noted that British strategy towards the Chagossians should be to “grant as few rights with as little formality as possible”. In particular, Britain wanted to avoid fulfilling its obligations to the islanders under the UN charter.

From 1965, memoranda issued by the Foreign Office and then Commonwealth Relations Office to British embassies around the world mentioned the need to avoid all reference to any “permanent inhabitants”. Various memos noted that: “best wicket… to bat on… that these people are Mauritians and Seychellois [sic]“; “best to avoid all references to permanent inhabitants”; and need to “present a reasonable argument based on the proposition that the inhabitants… are merely a floating population”. The Foreign Office legal adviser noted in 1968 that “we are able to make up the rules as we go along and treat inhabitants of BIOT as not ‘belonging’ to it in any sense”.

Then Labour Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart wrote to prime Minister Harold Wilson in a secret note in 1969 that “we could continue to refer to the inhabitants generally as essentially migrant contract labourers and their families”. It would be helpful “if we can present any move as a change of employment for contract workers… rather than as a population resettlement”. The purpose of the Foreign Secretary’s memo was to secure Wilson’s approval to clear the whole of the Chagos islands of their inhabitants. This, the prime minister did, five days later on 26 April. By the time of this formal decision, however, the removal had already effectively started – Britain had in 1968 started refusing to return Chagossians who were visiting Mauritius or the Seychelles.

A Foreign Office memo of 1970 outlined the Whitehall conspiracy: “We would not wish it to become general knowledge that some of the inhabitants have lived on Diego Garcia for at least two generations and could, therefore, be regarded as ‘belongers’. We shall therefore advise ministers in handling supplementary questions about whether Diego Garcia is inhabited to say there is only a small number of contract labourers from the Seychelles and Mauritius engaged in work on the copra plantations on the island. That is being economical with the truth.”

It continued: “Should a member [of the House of Commons] ask about what should happen to these contract labourers in the event of a base being set up on the island, we hope that, for the present, this can be brushed aside as a hypothetical question at least until any decision to go ahead with the Diego Garcia facility becomes public”.

Detailed guidance notes were issued to Foreign Office and Ministry of Defence press officers telling them to mislead the media if asked.

The reality that was being concealed was clearly understood. A secret document signed by Michael Stewart in 1968, said: “By any stretch of the English language, there was an indigenous population, and the Foreign Office knew it”. A Foreign Office minute from 1965 recognises policy as “to certify [the Chagossians], more or less fraudulently, as belonging somewhere else”. Another Whitehall document was entitled: “Maintaining the Fiction”. The Foreign Office legal adviser wrote in January 1970 that it was important “to maintain the fiction that the inhabitants of Chagos are not a permanent or semi-permanent population”.

Yet all subsequent ministers peddled this lie in public, hitting on the formula to designate the Chagossians merely as “former plantation workers”, while knowing this was palpably untrue. For example, Margaret Thatcher told the House of Commons in 1990 that: “Those concerned worked on the former copra plantations in the Chagos archipelago. After the plantations closed between 1971 and 1973 they and their families were resettled in Mauritius and given considerable financial assistance. Their future now lies in Mauritius”.

Foreign Office minister William Waldegrave said in 1989 that he recently met “a delegation of former plantation workers from the Chagos Islands”, before falsely asserting that they “are increasingly integrated into the Mauritian community”. Aid minister Baroness Chalker also told the House that “the former plantation workers (Illois) are now largely integrated into Mauritian and Seychellese society”.

New Labour continued the lie into the twenty-first century, continuing to peddle the official line in the court case that the islanders were “contract labourers”. As I write this, the Foreign Office website contains a country profile of the British Indian Ocean Territory that states there are “no indigenous inhabitants”.

Another issue that the British government went to great lengths to conceal was the fact that many of the Chagossians were “citizens of the UK and the colonies”. Britain preferred to designate them Mauritians so they could be dumped there and left to the Mauritian authorities to deal with. The Foreign Secretary warned in 1968 of the “possibility… [that] some of them might one day claim a right to remain in the BIOT by virtue of their citizenship of the UK and the Colonies”. A Ministry of Defence note in the same year states that it was “of cardinal importance that no American official… should inadvertently divulge” that the islanders have dual nationality.

Britain’s High Commission in Mauritius noted in January 1971, before a meeting with the Mauritian prime minister, that: “Naturally, I shall not suggest to him that some of these have also UK nationality …always possible that they may spot this point, in which case, presumably, we shall have to come clean [sic]“. In 1971 the Foreign Office was saying that it was “not at present HMG’s policy to advise ‘contract workers’ of their dual citizenship” nor to inform the Mauritian government, referring to “this policy of concealment”.

Ministers also lied in public about the British role in the removal of the Chagossians. For example, Foreign Office minister Richard Luce wrote to an MP in 1981, in response to a letter from one of his constituents, that the islanders had been “given the choice of either returning [to Mauritius or the Seychelles] or going to plantations on other islands in BIOT” [sic]. According to this revised history, the “majority chose to return to Mauritius and their employers… made the arrangements for them to be transferred”.

Ministers in the 1960s also lied about the terms under which Britain offered the Diego Garcia base to the US. The US paid Britain £5 million for the island, an amount deducted from the price Britain paid the US for buying the Polaris nuclear weapons. The US asked for this deal to be kept secret and Prime Minister Harold Wilson complied, lying in public. A Foreign Office memo to the US of 1967 said that “ultimately, under extreme pressure, we should have to deny the existence of a US contribution in any form, and to advise ministers to do so in [parliament] if necessary”.

A Foreign Office memo of 1980 recommended to then Foreign Secretary that “no journalists should be allowed to visit Diego Garcia” and that visits by MPs be kept to a minimum to keep out those “who deliberately stir up unwelcome questions”. The defence lawyers for the Chagossians, who unearthed the secret files, note that: “Concealment is a theme which runs through the official documents, concealment of the existence of a permanent population, of BIOT itself, concealment of the status of the Chagossians, concealment of the full extent of the responsibility of the United Kingdom government…, concealment of the fact that many of the Chagossians were Citizens of the UK and Colonies… This concealment was compounded by a continuing refusal to accept that those who were removed from the islands in 1971-3 had not exercised a voluntary decision to leave the islands”.

Indeed, the lawyers argue, “for practical purposes, it may well be that the deceit of the world at large, in particular the United Nations, was the critical part” of the government’s policy.