Document:De Beers to abandon cartel

| De Beers hit a high point in profit terms in the boom year 1989-90, but the following decade was to cost its shareholders billions of dollars. The break-up of the Soviet Union brought a flood of illicit diamonds on to the market, as did the civil war in Angola. In abandoning the CSO diamond cartel, Managing Director Gary Ralfe hopes to use De Beers' dominant position to persuade everyone in the industry to spend much more on marketing. |

Subjects: Ernest Oppenheimer, De Beers, Gary Ralfe, John Collard, IDSO, CSO

Source: The Guardian (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

De Beers to abandon cartel

De Beers, the diamond producer, is to abandon its 60-year policy of attempting to stabilise supply and demand in the world gemstone trade and concentrate instead on mining and marketing, The Guardian has learned. The move, which will send shock waves through the industry, is to be announced on 12 July 2000.

There will be fears of a re-run of the early 1930s, when gems flooded the market and prices collapsed, the event that led to the creation of the De Beers cartel. But the company believes aggressive marketing by the industry as a whole is a better way to boost demand and soak up supply than the operation of what has effectively been a private monopoly.

Henceforth, the company's London-based Central Selling Organisation (CSO) will cease mopping up spare diamond supplies around the world in order to hold up prices, and De Beers generally will abandon its role as international policeman for the industry.

In years gone by, this has involved the use of secret agents, freelance spies and a private intelligence network spanning Europe and Africa.

Now De Beers - shaken by the colossal expense of trying to stabilise the market during the turbulent 1990s - is to put its own shareholders first and aim instead to be the industry's "preferred supplier" rather than buyer and seller of last resort.

To stave off what would otherwise be a glut of stones on the market, De Beers is proposing instead massive saturation advertising and marketing around the world to beef up demand.

Recent research for the company by Bain, the management consultant, has shown that the advertising-to-sales ratio in the diamond business is just 1%, against 10% for most luxury products.

Managing Director Gary Ralfe hopes to use De Beers' dominant position to persuade everyone in the industry to spend much more on marketing, and has confirmed the company is to continue its famous generic advertisements with the slogan "A diamond is forever".

The CSO - which makes no profit at all on its operations - will continue to function, but primarily as the marketing arm of De Beers, whose own mines produce about half the world's diamonds. The accredited brokers and other buyers who, 10 times a year, visit Hatton Garden for the "sights", or London auctions - are to learn on July 12 of "new operating measures", according to a De Beers source.

De Beers hit a high point in profit terms in the boom year 1989-90, but the following decade was to cost its shareholders billions of dollars. The break-up of the Soviet Union brought a flood of illicit diamonds on to the market, as did the civil war in Angola.

Meanwhile, demand collapsed in the far east with the slump in Japan and the meltdown of the "tiger" economies in 1997-98.

In 1996, Australia's Argyle mine - the world's largest in terms of quantity - walked out of the De Beers cartel, and by the end of the decade De Beers had effectively abandoned price support for the lowest-quality stones.

The consequence of the diamond glut was that, by 1997- 98, the CSO stockpile of diamonds taken off the market in mopping-up operations had topped $5bn (£3.4bn), from $2.5bn in 1989, equivalent to a year's worth of CSO sales.

It has since been reduced, but the net effect of CSO operations in the 1990s has been that De Beers shareholders made no more money by holding the company's stock than they would have done by opening an ordinary bank account.

Despite the changes, De Beers has ruled out becoming a major player in its own right in the polished diamond business, preferring instead to supply rough stones to the major cutting and polishing centres. The Bain review highlighted the fact that the biggest profit margins in the supply chain are earned at the rough-diamond mining stage.

Historical gems

- The first attempt at a diamond cartel was made by Cecil Rhodes, founder of De Beers, once it became clear the mechanised diamond-mining boom of the late 19th century was producing so many stones that their rarity value was threatened. Rhodes was central control of supply as essential to the manipulation of demand.

- During the Great Depression, Rhodes' rudimentary cartel broke up and prices sank. In 1934, De Beers chairman Ernest Oppenheimer stopped the rot single handedly by effectively offering to buy all the diamonds in the world. This extraordinary gamble paid off, and the Central Selling Organisation (CSO) was born.

- By the 1950s, diamond smuggling threatened to undermine the cartel as Soviet-bloc countries sought stones for industrial and military purposes and newly affluent western consumers provided a ready market for illicit gems. De Beers hired Sir Percy_Sillitoe, head of MI5 from 1946 to 1952, to set up the International Diamond Security Organisation (IDSO).

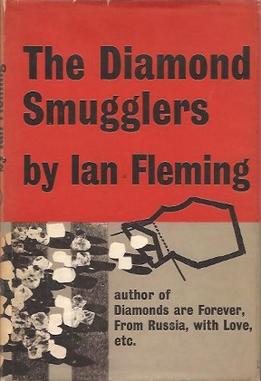

- Ian Fleming, the thriller writer, is contacted by an IDSO agent, John Collard, whom he meets in Morocco. The result of their conversations is a series of newspaper articles about the "million carat network", a book, "The Diamond Smugglers", and the James Bond novel "Diamonds are Forever" (1956).[1]

- For much of the post-war period, De Beers was officially barred from contact with both major players in the cold war, the US and USSR. The Soviet Union, a major diamond producer, claimed to have no contact with what it alleged was an offshoot of the racist South African regime. The Americans objected to the CSO cartel on competition grounds.

- In reality, both countries continued to deal with De Beers and the CSO. The Soviet Union maintained the closest relations - out of the public spotlight - while the Americans permitted De Beers executives to travel unmolested in and out of the US provided they stated they were on holiday.

- From the 1950s until the 1970s, and possibly beyond, diamond smuggling was to prove a vicious and cut-throat business, from the Cape to the streets of Antwerp. De Beers is reluctant to discuss its own casualties in the battle to control illicit diamond trading.

- By the 1990s, smuggled gems were fuelling Africa's longest and bitterest civil war, that between Angola's legitimate government, the MPLA, and the rebel forces in the north of the country, UNITA. With stones being routinely exchanged for weapons, De Beers felt obliged to amend its mopping-up policy to exclude what became known as "conflict gems".

- Today, the conflict in Sierra Leone is widely believed to involve smuggled diamonds exchanged by rebel forces for weapons. The exchanges take place largely off market, in Ukraine, Bulgaria and elsewhere, and De Beers is powerless to prevent them.