Document:China’s Strategy towards Europe: Implications and Policy Recommendations for EU Security

Subjects: China, hypercompetition, 21st Century

Example of: Integrity Initiative/Leak/4

Source: Anonymous (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

China’s Strategy towards Europe: Implications and Policy Recommendations for EU Security

CONFIDENTIAL

China’s Strategy towards Europe:

Implications and Policy Recommendations for EU Security

3rd June 2013

Contents

- 1 1. Executive Summary

- 2 Introduction

- 3 The Importance of Strategy

- 4 The Nature of Security and the Role of Hypercompetition

- 5 Chinese Policy towards the EU

- 6 Chinese Grand Strategy as it Affects Europe

- 7 The Competition for Resources

- 8 Investment as a Tool of Strategy

- 9 8. The Military Dimension of EU-China Relations

- 9.1 Defence Sales & Exports - The Developing Chinese Challenge to EU Markets

- 9.2 Chinese Defence Manufacturing Capability before 2002

- 9.3 The Chinese Defence Industry and Sales from 2002 to the Present

- 9.4 The Impact on the EU

- 9.5 How Chinese defence sales could affect Regional Security

- 9.6 Conclusions

- 10 9. Organised Crime

- 11 Cyber Security

- 12 11. Education

- 13 The Current Dynamics of the Relationship between Russia & China

- 14 The Impact of Chinese Global Activity on EU Security

- 15 The EU’s Strategic Response

- 16 A Summary of Policy Recommendations

- 17 ANNEX A

- 17.1 China’s Strategy towards Polar Regions

- 17.2 The Polar Sea Route

- 17.3 Mineral Resources in the Polar Region

- 17.4 China’s Developing interest in the South Pole

- 17.5 Resources on Land

- 17.6 Resources on the Seabed

- 17.7 Ice and Glacier Melt as a Source of Fresh Water

- 17.8 The Effects of Increased Commercial Activity and Ice Abstraction on Global Warming

- 18 ANNEX B

- 19 ANNEX C

- 20 Wikispooks edit: orignial chapter list

1. Executive Summary

For the better part of two centuries, the dominant global system has been shaped by Western culture and values. International economic and financial institutions set up by Western powers reflect Western interests over those of developing countries. Through its efforts, the West has succeeded in influencing in its own favour the global political, economic, social and cultural environment within which the world’s states, corporations and institutions and movements today compete vigorously for their place.

China is not seeking to find its place in this world system, China is determined to establish its place in the world on its own terms, to create an alternative system with different cultural values to challenge the hegemony of the Western system. China is pursuing this policy with a truly strategic approach; that is, not only with focus, coherence and determination, but also on such a global scale that China can hope thereby to change the global environment to favour itself and those countries which prefer the Chinese model to the current Western one. This is truly grand strategy, and China is demonstrating that it is adept at this, quick to learn and adapt.

A study of China’s strategy and tactics shows that China understand very well the hypercompetition that characterises today’s world and that, in this hypercompetition, states and other actors need to be able to employ many different kinds of power to succeed. Military power is still important, but it is by no means the only, or dominant, form of power. China is also demonstrating that it understands and can master the many forms of power and use them appropriately.

In its relationship with the EU – a major player in the global system – China’s strategy can now be clearly discerned. China has gone to great pains over the last two decades or so to study the EU and to identify what the EU has to offer China. As a result, China has been able to structure its approach to the EU in a way which maximises the benefit China gets from the relationship, whilst minimising the impact of EU culture, values and practices on China except in those cases where those practices might advance China’s interests.

As an organisation still very much in development, the EU, whilst large and strong, has not yet developed all the mechanisms and skills it would need to turn its latent strength into real, effective power. Strategic thinking within the EU, such as it has been, has been devoted to developing the organisation’s internal structure and functions and to the sharing of competencies and responsibilities between the central organs and with the member States. The EU has not yet developed adequate mechanisms or the teams of qualified people needed to enable it to think and act strategically in its external relations.

China understands this very well. In the EU-China relationship, China is acting strategically; the EU is not, neither are many of its Member States. As a result, the EU is being systematically out-thought and outmanoeuvred by China. The respect which China used to show the EU is being replaced by contempt on account of the EU’s perceived powerlessness. China is using the differences and disagreements between Member States to “divide and rule”. Through its carefully targeted investment strategy, focusing particularly on strategic industries and infrastructure, China is able to take full advantage of Member States’ need for or greed for money, exacerbated by the recent, ongoing, financial crisis in the West. Most Member States and EU institutions, preoccupied as they are with their own internal problems, see only what pertains to them of Chinese actions. Because they themselves are not thinking or acting strategically, they do not see the big picture. They do not recognise Chinese strategy for what it is.

The whole ethos of the EU is that of an organisation to which States adhere or aspire on the basis of their voluntarily signing up to what amounts to a code of values, standards and practices. All the EU’s internally focused grand strategic actions are inspired by this all-pervasive philosophy. The Partnership and Cooperation Agreements, for example, are designed to provide incentives, help and encouragement as States strive to adapt themselves to meet these, often demanding, rules so that their relationship with the EU can develop based on the mutual trust and respect that the voluntary adherence to a set of rules based on shared values and standards can bring.

The EU’s relationship with China was begun in much the same spirit, motivated by the conviction that China would naturally “want to be like us”. The relationship to date has been characterised by the EU’s offering a developing China access to the benefits of the EU unconditionally, engaging in trade without demanding reciprocity, accepting an asymmetrical relationship which opens the EU to Chinese companies but closes off large sectors of China to EU companies. It is hardly surprising that the EU is now seen as a resource that China can milk to develop its economy.

Not only have these well-meant blandishments failed in their purpose, but it is becoming ever clearer from China’s actions that they will continue to fail if they are persevered with, to the detriment of the interests of the EU and of its Member States. Indeed, in the face of all the evidence now available, for the EU to persevere with these recent policies would show that this benign EU philosophy had become a blind ideology. China does not want to be like the EU. It will not reshape itself in the EU’s image. In every facet of the relationship, be it in the legal investment strategy China is pursuing, in the “divide and rule” tactics towards the Member States, or in the activities of Chinese organised crime within the EU, there is complete consistency of approach. Far from China learning to work by the EU’s rules, China is trying and will continue to try to evade those rules. China has its own set of rules to work by.

This is the practical demonstration of a different culture. Western traders with China have understood this reality for centuries. Those who have learned to cope with it and adapt have profited enormously. Those who have not have failed, and have been swept away. The EU now has to learn to cope with this reality. To deal satisfactorily with China so that the relationship can be stable, harmonious and mutually beneficial, the EU must develop an ability to think and act strategically. There are no tactical or procedural solutions.

Detailed Policy Recommendations are given in the final section of this study. A brief précis of the main points of those recommendations is as follows:

EU Institutions

1. Create an informal strategy group within the EEAS, drawing on existing resources of talent. Develop this as a basis for a formal group.

2. Make a prior “impact assessment” of significant actions to be taken by all European Commission services.

3. Engage EEAS and Commission research instruments to undertake essential research on all key issues relating to EU security and China

4. Create a Forum of Asia-Pacific States, on the lines of NATO’s instruments for dialogue and cooperation, to discuss issues of regional security and cooperation. Chinese Relations with Member States

1. Monitor and regulate Chinese engagement with ad-hoc groups of Member States.

2. Find solutions at the EU level for the smaller EU Member States concerning their relations with China. 3. Ask Member States to inform the EEAS and each other of their contacts with China 4. Monitor Chinese immigrant communities in Member States.

Resources

1. Boost investment in energy efficiency research to reduce supply dependency. 2. Develop second and third generation technology which does not require back up fossil fuel power generation. 3. Develop shale gas resources to reduce European supply dependency. 4. Support the development of offshore resources in the Eastern Mediterranean region. 5. Support methane hydrates research as a source of significant future energy resources 6. Investing in natural gas vehicle technology to reduce supply dependence. 7. Build an Energy/Resource Relationship with Japan. 8. Identify those natural resources that raise the most significant supply security issues and design a substitution research programme around them.

Finance and Investment

1. Establish a centre within the EEAS to work with Member States to monitor and analyse Chinese investments and to disseminate information and engage in education on this topic 2. Improve legislation to close loopholes which allow China to operate unlicensed and unregulated financial institutions. 3. Establish a single system and a common accounting process for Member States to record foreign holders of public debt

Infrastructure

1. Initiate a study with Member States to establish a common minimum definition of the principal elements of national security and what constitutes critical national infrastructure and critical areas of their economy and society. 2. Publish assessed minimum standards (Red Lines) for ensuring that Member States maintain control of their critical infrastructure and economic assets. 3. Monitor especially Chinese investment in and acquisition of Member States infrastructure, supply chains and critical areas of their economy.

Trade

1. Press the Chinese authorities to be transparent about the ownership, composition and financing of all major corporations wishing to work in the EU. 2. Establish a process of reciprocity to compel China to open its markets to EU participation. 3. Work with Member States to improve the level of understanding, in governmental departments and in the corporate world, of Chinese policy, strategy and tactics.

Defence

1. Improve research into Chinese military developments, capabilities and capacities, and into Chinese defence exports and defence diplomacy (e.g. exercises with third party countries) 2. Sponsor seminars and workshops with Chinese defence experts to improve mutual understanding and confidence-building.

Law Enforcement

1. Strengthen Europol’s capacity to support Member States’ monitoring of internet sites advertising counterfeit goods and other products of Chinese organised crime. 2. Enable Europol to negotiate an agreement with China to track down and bring to justice those ringleaders of organised crime in Europe who are based in China. 3. Reinforce the European Cybercrime Centre to raise awareness and to support investigations in the Member States. 4. Increase the number of interpreters for Chinese languages and enable their sharing across the EU. 5. Encourage Member States to improve intelligence gathering on Chinese crime and to share the results 6. Improve cooperation with the Chinese authorities. 7. Improve European legislation on illegal drugs and counterfeit goods to enable more effective enforcement and prevent evasion of the laws.

Cyber

1. Establish an EU equivalent of the NATO centre of excellence in cyber. Resource it to monitor cyber incidents, establish an EU code of practice and agree a common approach to cybercrime 2. Improve legislation to make reporting of cyber incidents and risk assessments of the vulnerabilities of critical national infrastructure obligatory by Member States. 3. Modify the Framework R&D programme to prioritise cyber; a. Sponsor a comprehensive, technical research process and educate a new generation of “cyber warriors”. b. Sponsor work on defensive IT measures on a large scale. 4. Sponsor the EU to create a new, alternative web. 5. Publish Red Lines to help Member States check Chinese actions, beyond which national and EU interests would be damaged. 6. Co-ordinate between Member States.

Education

1. Encourage Member States’ reporting of Chinese educational initiatives, funding and conditions demanded, e.g. for establishing Confucius Institutes and language courses. 2. Monitor Chinese take-up of courses in Member States and publish details. 3. Sponsor the study and monitoring of Chinese global commercial, political and social activity. Generate a “China Studies” community amongst Member States.

Introduction

This Report provides an explanation of Chinese actions and intentions as they impact upon the EU so that the EU can develop its own effective actions towards China, enabling relations to develop more harmoniously between the two entities. For, if the EU and China continue on their current trajectories, future relations will be anything but harmonious.

In the preparation of the Report, the authors met with representatives of the European External Action Service, of the European Commission and of Europol. The authors drew on published sources and on interviews with individuals in Member State institutions, as well as with independent experts, academics and practitioners, including some resident in China. The conclusions drawn, however, are entirely the authors’ own. The team leader, who has prepared and edited the Report, takes full responsibility for all errors and omissions.

This Report, firstly, proposes a possible way of thinking about China and about the social phenomena involved. This way of thinking must be shared with and understood both by the Member States and by the EU institutions if effective actions are to emerge. It will help a great deal if our understanding and actions are matched by our allies.

Secondly, this Report examines Chinese actions and assesses the impact of Chinese strategy and tactics on Europe. It suggests how the mechanisms available to the EU to respond to this challenge might best be used, and what new or amended mechanisms are needed. In its recommendations, the Report also suggests ways in which EU Institutions might begin to compensate for any lack of political will on the part of, or conflict of interests between, Member States.

Thirdly, this Report highlights what we consider it essential for the EU to do to protect its internal security and the interests of the Member States. Tactical actions can never be an answer in themselves, but at least they can create a baseline from behind which the EU can develop its statecraft, formulate policies, and develop a process to build a grand strategy. Only such a grand strategy will enable the EU to advance the collective interests of its Member States and develop a harmonious, mutually advantageous relationship with China.

The recommendations are made throughout the text, and specific, detailed recommendations are to be found in the final section of the report. These recommendations are given in a real spirit of humility, knowing as we do how very hard it is to get things done in a multi-national environment. However, difficult is not impossible. To quote Confucius: “When it is obvious that the goals cannot be reached, do not adjust the goals; adjust the steps taken to achieve them”.

There are three issues fundamental to our being able to deal with China which must be thoroughly understood before we even begin to assess the Chinese position. These are: - the nature of strategy and grand strategy - the phenomenon of hypercompetition - the concept of security. Strategy, competition and security are English words in constant use within the EU. Yet, in the preparation of this Report, we have found such wide variations in understanding as to their meaning that it is essential that we begin the Report with an explanation and a definition of these key concepts. Indeed, striving for a common understanding and an agreed definition of these concepts across the Member States, taking account of the nuances of their different languages, cultures and histories, has emerged from our Study as one of the most urgent educational tasks for the EU to undertake.

With these concepts clearly laid out, the Report then addresses the factors that have shaped Chinese policy towards the EU and the strategy and tactics by which China seeks to implement that policy. Establishing the facts of the tactics has been less difficult than anticipated - there is far less dispute about those facts than might have been expected from so many different countries and institutions. Determining the intent of the policy and strategy is a far more contentious issue, requiring a greater exercise of judgement based on the knowledge and experience of the individuals contributing to the Report. This has underlined the importance of understanding China as it is, rather than as we would like it to be; of seeing circumstances and events through Chinese eyes, rather than through our own (which, given the diversity amongst Member States, is already a very wide canvas). It has specifically not been the task of this report to devote much of its limited resources to an assessment of what makes China what it is and what gives the country its special culture. A very great deal of intellectual effort is devoted to this topic elsewhere. But we have thought it essential to sketch out those features which we consider to be the defining elements of the Chinese understanding of security and strategy.

In understanding how the EU might best respond to Chinese actions, and might best develop a proactive strategy so as to ensure a harmonious and mutually beneficial relationship, the Report has been similarly constrained. It has not been possible to go into detail on all issues. We have concentrated on several important or high-profile issues as examples which demonstrate key principles. These principles, we would argue, provide a firm basis for future research, discussion, debate and action on a wide range of issues.

On the issues addressed in this report, which are fundamental to the future of the EU and to the prosperity and security of its Member States, it is no longer acceptable to say: “This issue is not within the competence of the Commission” or “There is no agreement on this issue between the Member States”. Those statements may be true, but they can be no excuse for inaction. Confucius again: “To see the right and not to do it is cowardice”. Identifying the gaps or inadequacies within the system must be merely the first step in remedying those inadequacies and filling the gaps. It has become clear in the preparation of this Report that, notwithstanding the acknowledged limitations of the EU systems, much more can be done within existing constraints and with existing resources. Our recommendations will draw out examples of some of these opportunities.

Throughout this Report we have attempted to be as objective and dispassionate as possible when assessing the Chinese actions and determining their intent. To be judgemental about an issue, to say that: “the Chinese are wrong to do this”, or that: “it is not legitimate for them to do this”, seems to us to be futile. The Chinese understanding of law, and therefore what constitutes legitimacy, is very different in many of its aspects from what we in Europe understand. If we always assess Chinese actions on the basis solely of our own cultural assumptions and convictions there will be no meeting of minds, only constant conflict.

This does not mean that the EU should not pursue what it perceives to be its own interests and advance the causes of its Member States- quite the contrary. But this in turn presupposes that the EU knows what these interests are and can assess how they will be best served. It also requires that the EU can correctly determine how China perceives its interests in the same case so that any potential clash of interests can be defused before it turns to conflict. This is the very essence of a grand strategic approach. The need for the EU to improve its ability in this area is the main conclusion of this Report.

The Importance of Strategy

Understanding strategy is one of the keys to understanding the security relationship between the EU and China. But there is a problem with the terminology which must be clarified if this concept is to be properly understood and used effectively by the EU.

Until relatively recently, the word strategy was used only in a military or a national/ international affairs context. Strategy was an essential tool - and the ability to think and act strategically an essential attribute - for coping with the complexity of war. But the expansion, over the past fifty years, of the use of the word “strategy” (and its equivalent in different European languages) so that it can now be applied to any topic at all, has diluted the meaning of the term and obscured its fundamental significance. Even in governments, the understanding of “Strategy” has become blurred because in many Member States they have lost the arts of Strategy Making and Strategic Thinking. We need to recognise that there is no quick, simple solution to the complex problems which now beset the EU, not the least of which is the development of a safe, mutually beneficial relationship with China. To resolve these problems will require the EU to provide itself with the capability for strategic thinking and acting.

‘Strategy’ and ‘Strategic thinking’ are qualities of statecraft. Once the EU has determined its policy in relation to China, that policy must be implemented through strategy. The term “strategy” describes the art of engaging at a high level of scale or responsibility with a live and vigorous opponent. The concept implies constant interaction. “Grand Strategy” considers the interaction between states at the highest level of scale.

Strategy must take into consideration the impact of the environment in which the engagement takes place and any allies or neutral parties, as well as considerations of the main protagonists. To confuse this way of thinking and acting with ‘a strategy’ - i.e. to focus only on ‘a strategy’ as a document or fixed plan, a series of actions, however thorough and detailed - would be a disastrous mistake. It would be to fail to recognise the all-important fact that strategy is constantly evolving. To succeed, it must be forward-thinking, innovative, creative, constantly changing, continuously or discontinuously. Strategic thinking must not be merely reacting to changing circumstances and unforeseen challenges, it must try to foresee the possible nature of those challenges and forestall them.

To be able to employ strategy and grand strategy, to think and act strategically, requires an institution (in this case the EU) to have a group of individuals with the competence and authority, formally or informally, to produce and implement that strategy. In some circumstances, countries and institutions can think and act strategically without formalising the process. If the leadership are well educated, understand the situation in a similar way, have a clear understanding of their interests, and can take action when necessary, the result can be real strategy. Whether formal or informal, the people who do, or who are tasked to do, strategy require a deep knowledge and understanding - of the environment, of the players (i.e. the EU, Member States and China) and of current events and circumstances. These people should possess strong intellectual ability coupled with an agility and flexibility of mind. Strategy also requires one to know what one’s interests are. For grand strategy, this means Member States’ national interests and the interests of the EU as an entity. Strategy must also address requirements and constraints and balance the two by prioritising. This requires judgement, which in its turn is based on a deep understanding of interests, short-, medium-, and long-term, and the values and principles by which these interests are determined.

The real utility of ‘a Strategy’, in the form of a published document, is in its ability to motivate a community to act coherently or in a self-disciplined way to achieve a shared objective. As such, it is a tool of leadership, part of the EU’s crucial “Strategic Communication” process. It will normally need to be paralleled by a confidential strategic assessment which must be constantly amended and updated as a basis for the EU’s strategic response. The openly published documents are part of the Strategic Communication action – they must inspire our populations and officials, but confuse our opponents!

The EU’s Strategic Challenge

The strategic challenge facing the EU is: In a dynamically changing world of over 7 billion people, most of them young, how can the EU best use its assets to influence the course of events? How can it maintain its place, ensure its security, create and exploit opportunities in the peoples’ interests? How can it transform its own institutions to cope with the drastic changes in the world and remain fit-for-purpose, whilst helping its Member States (particularly the smaller ones) to make the same transition?

The second (and commonly neglected) part of this strategic challenge is the challenge to think and act strategically. Unless the EU can achieve a better understanding of strategy and grand strategy, and enhance its capability to act strategically, the EU and many of its Member States will find it increasingly difficult to protect their security and advance their interests in the world in general, and in the rapidly developing relationship with China in particular, as the latter grows in importance as a player on the world stage.

The fact is that, for many years, the intellectual abilities of successive leaderships of the EU, and no small percentage of the leaderships of some of its key Member States, have been turned to thinking strategically only about the EU’s internal structure and functioning. External strategy has been neglected. This is understandable, given the way the EU has evolved. But it is no longer acceptable. Furthermore, it is well understood that many in the EU and in some Member States are uncomfortable with the idea of the EU doing ‘Strategy’ and ‘Strategic Thinking’ because, within the overall framework of governance and statecraft, these are more tools of leadership than they are of management. After a long period of relative peace, stable development and economic prosperity, many Member States have stopped thinking strategically. Without strategy and strategic thinking, essential organisations stop evolving.

Governments in many EU Member States have seen the growth of ‘management’ as the key to solving all problems. Risk is seen as entirely bad and threatening to the existing order. Self-interest begins to predominate as the sense of a need for collective, concerted action fades, and the sense of community interest is lost. Social responsibility and cohesion become fragmented and the concept of the “common good” gradually fades. Methodology takes hold, in which the process becomes the most important thing. Outputs replace outcomes as the key measure of performance and reward. It is to counter this internal tendency that the EU needs to develop its capability to do external grand strategy, however institutionally difficult that might be. If the obstacles to developing a formal capability are forbidding, then an informal capability needs to be built first. The most important component of strategy – competent, educated people – is available within the EU. These intellectual resources need to be harnessed as a first step; other components may need to be acquired or created. The checklist below identifies the essential and desirable components:

Resources which the EU (or a Member State) needs if it is to do strategy and grand strategy

- an adequately competent governance structure , well-staffed, capable of discharging the

strategic and grand-strategic responsibilities

- a body of people in all sectors of the EU (or national government) who are educated so that

they think strategically (from which can be formed a corps of qualified professionals when political circumstances permit) and who have: - broad education and formal training - experience, enabling learning - constant refreshing, updating and sharing of ideas

- a system to enable these people to understand (and keep pace with) the changing world,

including: - information gathering and analysis - research - experimentation

- a mechanism and process, formal and informal, to enable these people to do strategic

planning, comprising: - no single plan, but constantly renewed planning - cross-disciplinary team - cross-departmental process - inter-governmental links with Member States - when it becomes politically possible, a formal headquarters organisation as a base for the above processes

- a leadership mechanism to engage Member States in the strategy process:

- taking account of different views and incorporating them - providing a lead in a complex environment (especially for smaller states) - communicating what is necessary to communicate and keeping secret what should be kept secret - taking responsibility for error and redirecting as necessary

The Nature of Security and the Role of Hypercompetition

Security in the 21st Century

For most people in Europe and in those developed parts of the world which had grown up in the European, Westphalian tradition, states were defined by their geographical boundaries or by a single or dominant cultural identity. In these states for most of the 20th Century, security was understood as either “State Security” (counter-espionage or counter-subversion/terrorism- “internal security”) or as “Defence” (external security). The strength of a state’s armed forces determined its security in the international environment. States developed national institutions accordingly: armed forces; police; secret services; War/Defence Ministries, etc. all with separate, clearly defined functions. There was usually a clear distinction as to whether a country was at war or at peace.

However, this has changed as the 21st Century has advanced. Due to the rapid and profound changes in the global environment, the very nature of the instabilities and the resultant competition and conflict has changed. The potential for classic military confrontation and engagement is by no means over. But for a variety of reasons it is no longer the preferred means for many states (and, increasingly, non-nation-state actors as well) to compete and establish their place in the world. In some cases it is the cost of preparing for war, the uncertainty of its outcome and the subsequent economic and social impact which persuade states to pursue their interests by less “kinetic”, but no less fierce, means. In other cases it is the military preponderance of the competitor or, in the world as a whole, of the USA, which makes classic warfare less attractive as a means of advancing one’s interests, whether as a state or as a “non-state actor”.

The recent examples of Iraq and Afghanistan provide instructive examples of the limitations of classic military power. In the former, a conventional force-on-force engagement resulted in swift military victory for the superior military power, but saw the victors impoverished by the costs of stabilising a larger subsequent instability. In the latter, the world’s two most powerful military forces, the Soviet Union and NATO have each attempted to subdue the world’s fourth poorest nation - and lost. In doing so they incurred exorbitant costs, significant reductions in their global influence and serious damage to their interests (which in the Soviet case significantly contributed to the breakup of the country).

This issue has grown ever more rapidly as changes in societies around the globe have opened up vulnerabilities and have thereby created new opportunities for alternative forms of power to match classic military power in effectiveness. Military superiority is no longer necessarily best met by like alone – other forms of competition have displaced the simple arms race.

This requires that we define what we mean by power in each context; the power to do what? When we are confident that we know what forms of power we are likely to need in each case, then we can set about devising the kind of tools we will need to generate that power, and how these tools will interact when used in combination. Types of power might include diplomatic activity, economic action, development aid, political pressure, legal action, capacity building for good governance, security sector reform, and many others. This is not new. The British philosopher Bertrand Russell, writing in 1938 in his book “On Power”, showed that he really understood the different forms of power and their importance. But the ideas have been lost in the black-and-white world in which we lived during WWII and the Cold War which followed. We now need to regain that lost understanding.

The 21st Century Paradigm for conflict, as it appears to be developing, is characterised by the following features:

- The terms defence and security are not synonymous. Military and even economic might no longer guarantee security, (e.g. Israel has a strong economy and stronger armed forces than ever before, but this no longer brings the Israeli people the sense of security which it did in the past).

- There is no longer any clear distinction between internal and external security; what happens in Afghanistan or in Gaza has an instant impact in European countries with their growing Asian and Muslim communities.

- ‘Weapons’ used are not only military, indeed are not primarily military, but include many other forms of exercising power, e.g. economic, political, informational, electronic activity

- Victory cannot be determined simply by success in fighting.

- The default setting in peoples’ minds is uncertainty. It is not at all clear whether we are at war or at peace, nor what kind of threat we might be facing.

It is dangerous to assume that the traditional governmental tools designed for an earlier, simpler age - with which most EU Member States are still equipped – continue to be appropriate and effective. With European countries rarely spending as much as 2% of their GDP on defence, classic kinetic military operations are likely to be less and less an effective means by which they can exert influence and power.

Furthermore, because of the migration and resettlement of peoples, the ease of global travel, the availability of electronic communications and of information, today’s state is no longer simply defined by its geographical boundaries or by a single cultural identity. Its interests, therefore, are no longer co-terminous with its physical boundaries. The geographical territory is a meeting-place of networks of identity, communities-of-interest and loyalties. Today’s state is a “Network-state”, linked to other network-states, competing and conflicting with other network-states. Both the EU and China are best understood as “network-states”.

Another major feature of this “globalised” world is the multi-national company. Not only does international business link countries together (not a new phenomenon) but the larger companies have their own identities, jurisprudence, interests, culture and loyalties. They not only contribute to the network-state, but now effectively constitute “network-states” in their own right - independent players competing on the world stage. Their existence also complicates the relationship between the EU and China.

One practical result of this change - revolution is not too strong a word – in the nature of security is that, whereas 25 years ago most Western nations shared a common understanding of what constitutes security and what was needed to achieve it, this is no longer the case. Every EU member has a different concept of security. Sometimes these are formalised in a document (A “National Security Strategy”), sometimes not; sometimes there is a constitutional body charged with maintaining this concept or strategy.

This complete lack of common understanding gives rise to dramatically differing national policies. For example, some countries consider national control and ownership of key strategic assets (e.g. energy generation, water supplies, defence industries, hi-tech R&D) to be a key element of national security. Other countries, such as the UK, are happy to sell off these enterprises and elements of critical national infrastructure to foreign ownership, seeing the inward investment thereby generated as being more important than ownership or control. Indeed many question the notion of “ownership”.

A key task for the EU to initiate is a study of what constitutes national security, to point out where are the “red lines” which no Member State should allow to be passed. This would be a most useful starting point for developing a common understanding of national and collective interest and creating an EU capability for strategy-making and strategic thinking.

Hypercompetition

The predominance of military power as the defining power in the security relationship between states and other global actors has been replaced by a permanent, intense, all-embracing competition This, we assess, is the defining characteristic of the modern global environment, the practical manifestation of “globalisation” in which the EU must regulate its relationship with China. The term we are using to describe this new global environment is: hypercompetition.

Hypercompetition most effectively describes the nature of the relationship between the EU and China.

Hypercompetition is not just a sort of game. There are no agreed rules. It is bounded only by what you can get away with. This is the most prevalent and insidious form of instability in today’s world. Conflict and competition are being waged by ever more varied and ever less predictable means. What constitutes a weapon in this new “hot peace” no longer has to go bang. Energy, cash as bribes, corrupt business practices, cyber-attack, assassination, economic warfare, information and propaganda, terrorism, education, health, climate change or plain old-fashioned military intimidation are all being used as weapons of hypercompetition by many countries, China included. Because we are in a networked world, achieving a success in hypercompetition is not an issue of control; it is an issue of influence. We need to make ourselves alert to how others are trying to influence us, and we need to be aware of how everything we do will have influence. We need to use that influence consciously to achieve our ends. This is not an argument for cynicism, nor is it to say that everything we do should be calculatedly self-serving. But it is to say that we should not shy away from the fact that, for example, our international trade serves our political interests; that the circumstances created by our international intervention, be it with military force or stabilisation and development aid, should properly be exploited in our commercial interest.

China has clearly understood the reality of hypercompetition and the need to develop, employ and master the various forms of power (not just military power) that have utility in today’s world, China is consciously deploying these as tools in pursuit of her policy goals and to further her national interests. China is not the only country to do this, far from it. But not all countries have this understanding. Many governments, including in some Member States, have only the vaguest notion of the nature and intensity of hypercompetition.

In fact, Member States within the EU are in constant competition with all those around them, just as they, and the EU itself, are in constant competition with potentially (or actually) hostile states and organisations. Only the extent and nature of the competition will differ. The EU was founded specifically on the recognition that competition was fundamental to societies and with the aim of preventing that competition between European countries from escalating into armed conflict, as had so often happened in the past. But the EU has not done away with internal competition!

But, once hypercompetition is employed, and you are aware it is happening, you have no choice but to “join the game”. It is naïve in the extreme for anyone in the EU, in Member States’ governments, or even in major NGOs to think that they can stand aside from this process; that what they do can be somehow divorced from national or international interest or competition. An individual or a department within the EU can have the purest motives for their actions and can act out of pure altruism. But those actions will play into the hypercompetition nevertheless, and be judged by competitors accordingly. Those institutions, national and international, which do not develop this hypercompetition mind-set and do not realise the nature and extent of the process will find themselves ever more rapidly disadvantaged in their international relationships.

Chinese Policy towards the EU

Determining the intent of Chinese policy is much more difficult, and open to much greater differences of opinion and variations of judgement, than determining the facts of Chinese strategy and tactics as we observe them.

It is not within the remit of this Report to explore in depth the issues which have shaped modern China and which determine Chinese thinking, and therefore underpin Chinese policy towards the EU. However, as China sees the world through very different eyes and not from the Western perspective (which, in Europe and the US, is often mistakenly taken to be the right, or even the only, perspective), it is worth our summarising those factors which, in our opinion, have such a great impact on Chinese thinking that not to take these into consideration will result in our failure to understand and correctly interpret Chinese policy initiatives.

The first such factor we take to be the ancient traditions of Chinese culture and lessons of past history as the longest surviving polity on the planet. China has been a nation state since 206 BCE and by 41BCE was already half its current size. Although, as it expanded, the Han state absorbed other ethnicities, it absorbed these fully into its culture. China has never been multi-cultural. 90% of the Chinese population think of themselves as the same race. There is an unparalleled correlation between culture/civilisation and state. Confucius’ philosophy of the primacy of the state, society and the family, in that order, has always been at the heart of this culture. The cult of the individual has never had hold in China. Preservation of the culture and security of the state, therefore, are at the root of China’s policy today, as they were in ancient times. The state is the personification of the culture. The wisdom of China’s strategic thinkers, most famously Sun Tzu, and their skill in understanding and applying the principles of politics and war in defence of the state, still guide policy. Chinese who leave China carry this culture with them and bring a piece of China to wherever they settle as a community, maintaining their link with the mother country. This contributes to modern China’s ability to act as a network state par excellence.

The second factor we assess as China’s experience in the 19th& 20th Centuries of being at the mercy of foreign powers, from the Opium Wars of the British and other Europeans, to the Japanese WWII invasion and the subsequent Soviet influence. Within living memory, China has had very painful experience of several catastrophic disasters which have wiped out large parts of the Chinese state and which have been beyond the power of any group or Party to fix. The basis of Chinese policy today is how to cope with this challenge and prevent it from happening again.

This experience of humiliation, fragmentation and disorder has provided Chinese policy with its obsessions with preserving unity, with ensuring China’s ability to keep foreign influence and interference at bay, and with ensuring that China, as a nation state and as a culture state, can take its rightful place in the global order. This global order is one in which China will not accept the hegemony of any other nation or culture. Anti-hegemonism, i.e. countering the perceived US and Western dominance of the global system, is one of the fundamentals of China’s policy. China is striving to create an alternative system, seeking as allies in this endeavour those countries that feel disadvantaged by the current (US-centric) system or which the US system considers pariahs.

Security and independence require that China be self-sufficient in materials. That access to essential communications, trade and supply routes, be guaranteed. Survival also requires China to ensure that it is fit to adapt and flourish in today’s rapidly changing world. Learning and adaptation, however, must not threaten the integrity of Chinese culture nor imperil unity. Whereas Europe is moving towards smaller political entities within a federal framework, China’s policy default setting is to move in the opposite direction.

This is not to say that China is monolithic - far from it, although China’s information strategy seeks to present it as such to the EU, often successfully. Commercial corporations which are developing from state enterprises are coming to have their own agendas; different regions are almost city-states; wealth, class and family still influence politics; there are many tensions within modern China that could still tear the country apart. A study of where the power lies in China, and who makes policy, is a very worthwhile occupation. One reason for China’s government to seek always to present a united front to the world is to dissuade competitors from exploiting these differences and vulnerabilities. That said, the Chinese approach does have a natural coherence and there is a much greater shared understanding and vision than one finds in many other large countries, not to say entities such as the EU.

The third factor reinforces this coherence. From their Soviet allies, the Chinese absorbed an admirably comprehensive, intellectually coherent, highly disciplined and precise structure of thinking. This provides them with a most valuable framework for the rigorous development of policy and strategy, and makes it easy for them to educate a large body of people in that way of thinking. The framework encompasses all supporting aspects, forcing students of the method to take into consideration such issues as equipment acquisition; education and training; gathering information, etc. in no way is this a restrictive process, nor is this something limited to military or security thinking.

Maintaining the Communist Party in power, and ensuring it has as much of a monopoly of power as possible, is the fourth main factor moulding policy. But the Party, for all its nepotism and accusations of personal corruption, has seen the need to adapt, indeed to devise a mechanism for constant adaptation. Once the Party becomes a drag on efficiency, it will have outlived its usefulness, just as happened in the USSR. So far, the Party has succeeded in “riding the tiger” that is today’s fastdeveloping China. It is determined to continue to do so.

All these factors together not only give Chinese policy towards the EU a high degree of coherence, they also imbue it with and unmatched capacity for long-term thinking and acting. The short-term perspective of Western, democratic politics and of Western business means that the EU institutions invariably tend to interpret Chinese actions from a misleading, short-term perspective. The underlying long-term intent is obscured. This is perhaps the most important practical point to understand about Chinese policy. Coupled with the strategic aim of achieving the fitness to operate effectively in the rapidly changing global environment of today (rather than simply seeking world dominance, which is how China is often perceived), and the understanding that the ability to adapt is the crucial quality to enable survival in this, as in any, eco-system, an appreciation of China’s longterm vision is the lens through which we must evaluate all China’s actions towards the EU.

Chinese Grand Strategy as it Affects Europe

Chinese policy towards the EU is implemented through its Grand Strategy. In addition to the above discussion of strategy, security and hypercompetition, there is one more important aspect of today’s world that has a bearing on how states and international institutions develop their Grand Strategy. That is, that the environment itself is a major factor. To understand the significance of this as it affects the China-EU relationship, it is best to consider that relationship as developing within an ecology, in a Darwinian sense.

Just as living things compete with each other and at the same time struggle against the natural environment, so to do societies, states and other actors in the world’s political and economic environment – i.e. hypercompetition. The environment, natural or political, is constantly changing. Just as Darwin noted that the animals most likely to survive and flourish were not the largest or the strongest, but those best able to adapt, so the same can be said about societies and their institutions. Indeed, Marx made exactly that point in 1855, commenting on the revolutionising impact of war on societies incapable of adapting.

The Chinese have understood Darwin and Marx, and they understand that not only do environments change, but that they can be changed. Mankind is changing the earth’s natural environment through carbon emissions. China understands that, because of its scale, its actions will change the world’s political and economic environment significantly. China is therefore seeking to ensure that its impact will change the global environment in its favour. This is a most important point. It means that the EU, as itself a global actor, needs to understand that China’s impact on EU security is not only through its dealings with the EU and its member states, but through its actions worldwide. These are not secondary or incidental, but primary effects. The evolution of the EU-China relationship is taking place against the background of a changing environment. That environment - political, economic and cultural - is being deliberately and systematically changed by China, as best it can, to favour itself and disadvantage its competitors, including the EU.

Strategy in Practice: The Key Role of Knowledge

To change the world in your favour, of course, firstly you need to understand it; secondly, you need to make yourself fit to operate within it. Knowledge is the key. For most of the 1980s, China was reaching out tentatively to the world from which it had been isolated by Mao and the Cultural Revolution. China understood well the need to catch up, the need to understand what it had lost and what it needed to relearn if it was to regain what it saw as its rightful place in the global order and to avoid being a plaything of other countries. By the early 1990s, China had settled on three essentials to be at the core of this catch-up programme; the English language, computing, and what we would call “competitive intelligence”.

“Competitive intelligence” or “business intelligence” is a Western term used to describe ethical spying on one’s competitors. It is perhaps the most appropriate term to describe the process set in train by China. The Chinese had observed (and indeed had experienced at first hand) the longrunning US cross-departmental initiative to study systematically other countries’ government and commercial scientific programmes. Maintaining a strong technological lead over all other countries, close allies included, is still today at the core of US strategy. By the mid-1990s, China had begun its own comprehensive intelligence-gathering programme on similar lines, but on a vastly greater scale. Furthermore, the Chinese brought to this programme their own understanding of the world as an interaction of networks. China understands that, in a networked world, neither it nor any other polity can control everything, only influence things; and that the actors are not limited to nationstate structures. They understood that large multi-national companies and international organisations operated as quasi-states and were also worthy targets. The intelligence process they have in place today is unparalleled in its extent and comprehensiveness. Nor is it just informationgathering. China has set up a system to evaluate and learn from the knowledge it gathers, to apply it in a way that helps develop Chinese society and advances Chinese interests.

This system is now fundamental to all Chinese interaction with the EU, as it is with the rest of the world. It employs the traditional collection methods of diplomacy, “friendship societies” and spying, of course. But it is in its other collection tools that the system is so remarkable in its extent and depth. These include “cyber warfare” and “hacking”, discussed in detail below. They include exploitation of the Chinese Diasporas wherever these are amenable to collaborating. They include paying foreign commercial companies to obtain information. They include China’s huge academic outreach programme, also discussed in detail below; and they include China’s business and financial initiatives worldwide, a case study of which is given below. This, it must be reiterated, is not something which is a threat to the EU by China; it is the reality of everything China is doing with and to the EU.

China’s Strategic Understanding of the EU

China, then, has studied the EU very closely and understands it very much better than the EU as a whole understands China. Because China can both think strategically and can implement a highly coherent, flexible strategy (which the EU as yet cannot), it understands that the EU is simultaneously a competitor, an opponent, a market, a source of knowledge and an ally and, depending on the circumstances, treats it as such. It understands the economic weight of the EU and is determined to benefit to the maximum by exploiting that in China’s interests. Through its competitive intelligence process China knows exactly how to do that, and exactly what the EU and each Member State possess which would be to China’s benefit. It also understands the weaknesses of both the EU and each of its Member States, the EU’s lack of political unity, and how to exploit those weaknesses to its advantage. As China modernises and grows, there will be less need for the EU as a market, or it will become a competitor and a supplier of high tech goods designed in China.

China has come to have a particular disdain for the EU’s central institutions on account of their weakness and because of the EU leadership’s inability or unwillingness to use the organisation’s strength as power. China respects power, recognising that it comes in a wide variety of forms, not just, for example, military. An example of the EU’s failure to turn its strength into power can be seen in the EU’s willingness to deal with China without demanding reciprocity, to allow China freely to take advantage of the EU.

For the EU to engage unconditionally with China in the hope or belief that this will evoke an analogous response from China, or will somehow influence China to liberalise, to become like Europe or to adopt European values, is a serious psychological mistake on the part of the EU. This is seen as weakness and evokes only contempt, actually increasing the Chinese temptation to profit from the EU’s perceived powerlessness. China has a very clear understanding of what it thinks its interests are and it will pursue those interests mercilessly. If the EU wants to influence China’s behaviour, it will only be able to do so from a position of strength and with a demonstration of the appropriate form of power. Empty political gestures or declaratory statements by the EU or the European Parliament, if not backed up by the application of power, will be dismissed out of hand.

Divide and Rule

An analysis of China’s dealings with the Member States indicates that China today identifies a fivetier Europe1.

Tier one consists of Germany alone. Germany is the country which China thinks has most to offer it. The two economies are compatible, macro-economically. Germany is responsible for 44% of total EU trade with China and is the chief funder of the EU and Eurozone and is therefore more important a power centre than Brussels. China is keen to get German technology and managerial expertise. German companies want Chinese money. Germany is also seen as a tough, competent partner and, as a consequence, gets China’s respect as well as, unfortunately, a great deal of attention from Chinese state-sponsored cybercrime. Having identified Germany as the main power-broker in the EU, China has now started trying to use Germany as a weapon to weaken Brussels' competence to set trade policy, which is the sole remaining power Brussels has that China knows can actually do damage to its interests. Whatever the rights or wrongs of decisions taken by Brussels in the trade field, trying to overturn Brussels’ decisions at the behest of China weakens the one area where Brussels can still make a difference. Premier Li Keqiang chose Germany as the first country in the EU to visit in May 2013 – and did not come to Brussels.

Tier two is formed by the Nordic countries and the Netherlands. They are seen as being like Germany, but on a much smaller-scale, and consequently given less attention.

Tier three includes France and the UK. The Chinese perspective appears to be that these two countries have an inflated sense of their own importance, largely due to their historical baggage as former major colonial powers. China considers that the two former powers act as if they still carry substantial weight in the world, but also assesses that they can no longer turn their ambitions into reality so easily because their national institutions have not evolved to keep pace with the times and are largely obsolete. As a consequence, China perceives that these countries sometimes take actions beyond their real capabilities that fail to impact or that backfire. They expect that trade will follow a

1 It is appreciated that this is a very rough-and-ready analysis, that we could debate exactly where some countries lie, and that it leaves out some countries that do not fit easily in one tier or straddle tiers (Belgium, for example). But it is borne out quite consistently by China’s dealings with the Member States and it is a useful tool when we are assessing China’s strategy.

good political relationship, rather than vice-versa. They do not fully understand Chinese thinking and often miscalculate in their dealings with China.

Tier four is comprised of countries that joined the EU from in 2004 onwards, plus candidate states from the Western Balkans. There is quite a lot of diversity within this complex group, and it may subdivide. But for the moment there is enough commonality for China to try to treat them as one subregional group, as discussed below. China’s relationship with these countries also reflects the tensions between China and Russia and between Russia and Germany, particularly on energy issues as regards the latter, where they look to Brussels for support. Many of these countries offer a suitable base for Chinese operations in Europe and as a channel for trade. For historical reasons, Romania has the strongest relationship with China. Poland and the Czech Republic are seen as the most robust and competent, and Poland is viewed as the country with the best strategic thinking in the group.

Tier five is Southern Europe. These China sees as countries which have been the most economically and institutionally weakened by the global financial crisis and therefore present a soft underbelly through which China might be best able to penetrate certain European markets. Some of them have enough weight of technological and managerial excellence to warrant serious attention from the “competitive intelligence” operation. Some have political systems in which politicians and industrialists are seen as being more open to personal, informal financial blandishments than in some more northerly Member States.

Based on this pragmatic strategic analysis of Member States, China is today pursuing a fairly blatant policy of “divide and rule”, paying as little respect as possible to the EU’s central authority, and indeed, seeking to lessen that authority. Making good use of the access it has enjoyed through the EU-China Strategic Partnership, China has spent the last decade or so gaining a really good understanding of the EU and how it functions. It has noted the weaknesses of central institutions; it has seen that Member States are acting increasingly in their self-interest and independently of Brussels, rather than for the benefit of the whole. As a consequence, China now gives higher priority to its direct relationships with Member States than it does to its relations with Brussels. China prioritises its relations with the Member States based on a balance between China’s perceived interests and the opportunities offered by the mind-set or by the problems and vulnerabilities of each state. Again, it would appear that China has overall a better understanding of Member States, their strengths and weaknesses, than many of the Member States have of China. Certainly China has been observing Member States vying for preferential access to China, and naturally uses this to manipulate them, playing them off against each other and lobbying individual Member States to try and influence central EU decision-making when this suits.

Nowhere is this Chinese attitude better illustrated than in its current policy of “splittism”, i.e. dealing with ad hoc regional groups of Member States, as noted above. EU Member States have a perfect right to deal bilaterally with China. But China is making a concerted effort to encourage countries at sub-regional level to form blocs to work with China. This is in flagrant disregard of the EU’s stated wish to China that other countries deal either bilaterally with Member States or through Brussels. China is increasingly creating these sub-regional blocs to work with in its own interest, especially amongst the newer, smaller and/or economically-stressed EU Members, thereby simultaneously weakening Brussels and strengthening its own influence with those Member States.

These smaller Member States are often in the situation of trying to raise their profile in China and are frustrated that they cannot get the same level of access and attention as larger States. Acting within regional subgroups get them meetings with the Chinese leadership which they could not otherwise get. As a result of its careful “grooming” of selected Member States, China can now rely on some countries to be more favourable to its policies and to support its cause in Brussels. By contrast, Member States – particularly the larger ones - which take positions on issues which oppose Chinese policy are “put in their place” with diplomatic snubs, such as that meted out to the UK for its very public political welcome of the Dalai Lama in 2012.

The increasing contempt which China is showing towards the EU’s institutions is matched by its treatment of the European Parliament. Having developed close relationships with various political groups at the European Parliament and, through them, having come to understand the weakness of the European Parliament and how easily it could be manipulated, China realised that it could ignore its former parliamentary partners’ wishes with impunity. It chose, therefore, to host this year’s EUChina party political forum on its own terms in China, favouring invitations to national parliamentarians rather than to MEPs, without consulting their original hosts. This was probably also because of the European Parliament's regular high profile taunting of China on its human rights record. As it is the turn of Europe to host the event in 2014, we wait to see how the Chinese will play it next year.

If all these instances are considered separately, they could be dismissed simply as “normal” diplomatic manoeuvring. But, considered as part of a coherent strategy, they can be recognised as an increasing trend on the part of China to diminish the EU and undermine its solidarity. This trend provides evidence that China’s attitude to the EU has changed over the past decade, moving further away from “partner” towards “competitor”, Chinese protestations to the contrary notwithstanding. The hypercompetition is hardening and the sooner this is understood in Brussels, the better. The next step to look out for is a regional subgrouping of EU Member States to accede to a Chinese request to create its own secretariat or a permanent HQ of any kind to work directly with China. If there is ever a temptation for any such structure to be created by a group of Member States, a dangerous precedent will have been established. This must be a “Red Line” for the EU and its Member States.

The Competition for Resources

We have noted above the Chinese capability, through its scale and through its focused grand strategic approach, not only to engage effectively in competition with the EU, but also to change the very environment in which that competition takes place. In this respect, the carefully planned Chinese acquisition of assets and resources worldwide has a huge impact on the internal security and wellbeing of the EU.

The EU so far has failed to appreciate three parallel factors which strengthen Chinese relative power and weaken that of the EU. The first is the dramatic increase in the scale of Chinese acquisitions worldwide, both in developed and developing countries. Some of these acquisitions are innocuous and understandable from a purely commercial perspective. But other acquisitions, initially primarily in developing countries, but nowadays increasingly within the EU’s territory, must be seen as having a strategic aim. These acquisitions give China significant control of key infrastructure, or exclusive access to key resources. For example, they lock in control of fossil fuel and mineral resources for China over the longer term.

In terms of resources, this first factor is reinforced by a second factor - the increasing strategic vulnerability of EU, particularly in respect of fossil fuel resources. The EU faces a decline in conventional resources, whilst the United States, China and others are beginning to exploit unconventional fossil fuel resources on a large scale.

The third factor is the increasing ‘resources isolationism’ of the United States. The US increasingly has less need of Middle Eastern energy resources and may well take the view that the Chinese search for resources is not of a strategic interest to the United States.

These factors together expose significant strategic threats to the European Union: increasing energy vulnerability in a world where everyone else will become less vulnerable; a growing likelihood that the United States cannot be relied upon to protect the external economic interests of the European Union, and; increasing Chinese lockdown of fossil fuel and natural resources. The US economy needs to expand in the developing world more than in a Europe, where it is already in a strong position.

The Scale of Chinese Acquisitions and Operations

It is the scale and clear strategic focus of Chinese activities which creates the impact on the global environment. The International Energy Agency (IEA) assesses that by 2015 China will be producing 3 million barrels a day (mbd) of oil outside China. In 2012 alone China made $35 billion of acquisitions in energy infrastructure. Sinopec alone has made acquisitions totalling $92 billion since 2009.In addition to energy, there are specific concerns in respect of specialist mineral and rare earths, which surfaced in 2010 when China stopped shipments of rare earths to Japan.

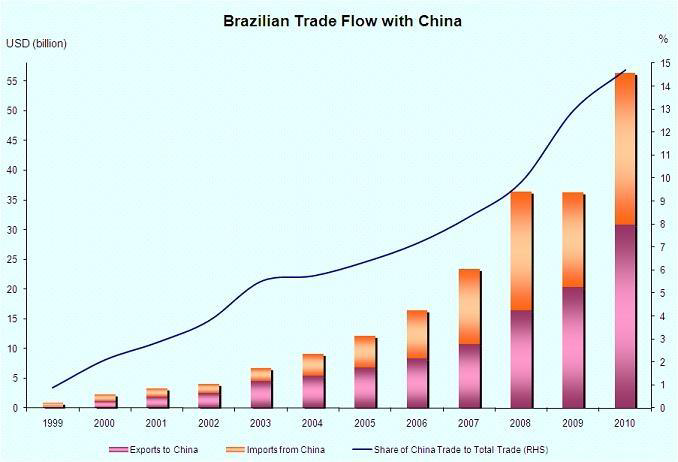

In Africa, Chinese trade in 2011 was $106 billion. This is ten times the trade level of 2000. Over 800 Chinese state owned companies are now operating in Africa. China is now the third largest investor in Latin America with acquisitions of $23 billion (total scale of investments between 1990 and 2009 amounted to $7.3 billion). Whilst Chinese experts argue that this investment is purely commercial and is deployed to feed the needs of the world’s no.1 manufacturing power, it would be naïve to ignore the foreclosure effect of limited resources being placed in Chinese hands.

China, the EU, and Energy Security

China’s impact on world markets as an energy importer is well known. But China’s efforts to reduce its energy dependency, and the vulnerability this brings with it, are less well known. Chinese Plans for the development of shale resources are well advanced. China has larger shale resources than the US, estimated at 36 trillion cubic meters (tcm). Initial Chinese plans estimate 60 to 80bcm production by 2020 and there is significant potential for shale oil.

It is true that China faces several obstacles, from water shortages to pricing structures, in the gas sector. However, potential energy security advantages are immense. There is a very high likelihood that China will develop these resources over the next decade. New technology, for instance liquid natural gas fracturing, may mean that the Chinese do not have to use water in the extraction process.

However, in the medium term, China will need to increase its energy imports and this will bring it into increasing competition with the EU, often in “difficult” parts of the world. China’s investment in infrastructure in the Middle East; Chinese engagement with Iran, Venezuela and Argentina; and China’s buying up of EU technology companies and sending of students to technology centres in EU universities are all relevant to this competition.

Because we so often operate in stovepipes, European energy specialists concentrate on deals which affect them directly, and overlook Chinese energy acquisitions worldwide, including acquisitions into unconventional resources and particularly into technology. China is developing a knowhow and technology base to exploit its own domestic unconventional fossil fuel resources. We should expect China to become a much more powerful player in the energy field in the coming decade. This will inevitably have an impact on the EU’s energy security.

The China-EU-US Triangle

The EU’s energy security and the EU’s relationship with China will both be impacted by developments in the United States. Thanks to shale gas, the US is already ‘independent’ in gas for the foreseeable future. The ‘on-shoring effect’ of manufacturing moving back to the United States (to take advantage of cheap gas) is also making Europe more vulnerable. As this trend develops, it will make the US less dependent on Chinese manufacturing supply chains and therefore able to contemplate a much more isolationist economic and security policy. Furthermore, the US is likely to be ‘independent’ in the production of oil by 2020. This may well be an under-estimate due to the fact that the cheap price of gas has seen a major switch in drilling to shale oil plays across the continental United States, and the imminent use of gas as a motor fuel on a large scale will further reduce oil demand.

The strategic impact on Europe of US energy independence could be considerable. The US will no longer need the Middle East for its own energy supply security, just at the time when China will be seeking to buy significantly more energy. Not only does this explain the Chinese interest in investing in acquisitions in the Gulf and its engagement with Iran, it also provides a significant motive for China’s increased defence spending. For six decades, the EU and many of its Member States have been able to reduce defence spending to a very low level, safe in the belief that the US would continue to invest in military strength in Europe and the Middle East. This investment can no longer be assumed. At the very least the EU will be faced with demands for greater security investment in the region. Indeed, one day the EU may be forced to replace the USA militarily in the Mediterranean and Middle East region.

Declining Energy Resources in Europe

To compound this complex strategic picture, the EU’s own energy security situation is deteriorating. The North Sea resources (Europe’s principal fossil fuel resource base) are declining rapidly. Eastern Mediterranean gas may provide some support, but it is open to question how easily that resource base will be developed given the ‘above ground risk’; i.e. the Law of the Sea disputes in the region; the Cyprus question; Israeli-Palestinian conflict. North African resources are becoming increasingly problematic because of the security situation in the Maghreb.

In fact, as Latin America, China and the United States (and probably India and SE Asia too) develop their energy resources, Europe will become the most strategically vulnerable in energy terms of any major bloc on the planet. Paradoxically, this European vulnerability may well be reinforced by a collapsing oil price. This process would come into place as much larger quantities of fossil fuels come on stream. A strategic downward shift in the oil price could generate significant instability in both the Russia Federation and Saudi Arabia, negating the potentially positive economic effect of cheaper oil.

The danger for Europe is that China will have locked down sufficient external oil resources and have domestic gas supplies, whereas Europe will remain much more vulnerable to any instability. The EU’s security would decline relative to that of China, and it might bring the EU into much sharper competition, even conflict, with China.

Investment as a Tool of Strategy

Investment is currently China’s single most important tool of strategy, both internally and externally. A study of where and how China makes its investments is as good an indicator as we will get of China’s policy objectives and strategic thinking. A key theme running through this report has been the importance of seeing “the big picture” if one is to understand Chinese strategy. Nowhere is this more telling than in a study of China’s investments.

We have touched upon this several times in other sections of this report, for example in the competition for energy and scarce mineral resources addressed above, and in the global reach of China’s strategy, as exemplified in Chinese interest in Latin America or the Polar regions, details of which are given in the Annexes to this paper. An investment, or even a trend in investments, can appear totally innocuous if assessed in isolation. That same investment can take on another significance altogether if assessed in conjunction with other activities, or if seen as part of a global pattern.

There is now a considerable degree of awareness in Europe of the fact that many Chinese corporations have such a close link with government bodies that they are effectively instruments of state power. The investments and acquisitions these “private businesses” make need to be viewed in this light, even though many of the European commercial or financial institutions (and frequently the Member State governments) involved in these deals -with an eye to the short-term political or financial gain they bring - would prefer this question not to be asked. The EU has a most important role to play here. Because of its position and the resources it has available, the EU can and should be the organisation which sees the big picture and brings this to the attention of its Member States, informing the governments of those countries which are not big enough to have this ability, and being the conscience of those which might be tempted to ignore long term or collective interests for short term individual gain.

The pattern of Chinese investment in Europe also helps us to understand something else about the nature of China’s dealing with Europe. That is, the extent to which Chinese State activities reflect cultural attributes which European traders who have done business with China over the centuries have always understood, but which European diplomats sometimes seem to have difficulty seeing. That is, the Chinese are great businessmen. They are natural risk-takers; they have a great eye for a bargain; they will exploit a weakness ruthlessly; they will work according to their own rules, not yours; they can be relied upon to exploit every loophole in the law, contract or agreement to achieve an advantage.