Dick Ellis

( officer, spook) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13th February 1895 Sydney, Australia |

| Died | 5 July 1975 (Age 80) Eastborne, UK |

| Alma mater | St Edmund Hall (Oxford) |

| Founder of | Interdoc |

| Interests | |

British intelligence officer who worked against the Soviet Union. Also at the British Security Coordination. | |

Charles Howard Ellis, better known as Dick Ellis, was an Australian-born British intelligence officer.

He fought the Red Army during the British intervention during the Russian Civil War. In December 1923, Ellis became British vice-consul in Berlin: there and elsewhere he maintained surveillance on White Russians fabricating intelligence documents for the British Special (Secret) Intelligence Service.

According to Ellis he began "providing a great deal of information on German rearmament" to Winston Churchill during the 1930s.

He worked for the biggest and most important British covert operation during WW2, at the British Security Coordination, a campaign to bring the United States into the war.

Contents

Early Life

Ellis was born in Sydney, to parents who had emigrated from Devon, and spent his early life in Melbourne and Tasmania. In 1914, he travelled to England, intending to study at Oxford University.

Following the outbreak of the First World War (1914–18), Dick Ellis enlisted as a Private in the Territorial Force, and became part of the 100th Provisional Battalion, which later was renamed the 29th CITY OF LONDON Battalion. He saw action on the Western Front and was wounded three times, before being commissioned as an officer in September 1917.[1]

In 1918, he transferred to the Intelligence Corps and there served for several months, before the Armistice of 11 November 1918. In 1919, Ellis then was sent to Transcaspia, as part of the Malleson mission against the Bolsheviks in Turkmenistan, and also was involved in fighting the Red Army in other places, including ordering summary executions of prisoners of war. He participated in the British invasion of Afghanistan in 1919. That same year, Ellis was awarded the OBE (military) for being a good soldier.[2]

In 1922-23 he was a captain, Territorial Army Reserve, based in Constantinople on intelligence work.[3]

Secret Intelligence Service

After leaving the army, Ellis resumed his studies, learning Russian at St Edmund Hall, Oxford and the Sorbonne.

He joined the Secret Intelligence Service in Paris in 1923.[4] Ellis held diplomatic and consular posts in Turkey and the Balkans. In December 1923, Ellis became British vice-consul in Berlin[1] and later worked in Vienna and Geneva as foreign correspondent for the Morning Post. While in Geneva, Ellis wrote a major book on the League of Nations. Although for long attributed to British-Finnish League official Konni Zilliacus, it has been proven that Ellis was the real author.[5] In 1938 he was brought back to England to supervise the German embassy's telephone lines. Ribbentrop's staff soon developed an uncharacteristic discretion during telephone conversations. Ellis was subsequently sent to Liverpool to establish a mail censorship centre.[4]

He was the handler of White Russian emigre general Anton Turkul.

Ellis was giving work as foreign correspondent for The Morning Post as a cover for his intelligence work with MI6. During this period he was in Vienna, Geneva, Australia and New Zealand. In the 1930s he came into contact with the businessman, William Stephenson. According to Ellis he began "providing a great deal of information on German rearmament" to Winston Churchill. He went on to argue that although Churchill was not in office, "He was playing quite an important role in providing background information. There were members of the House of Commons who were much more concerned about what was happening than the administration seemed to be at that time."[3]

British Security Coordination

In summer 1940 he became deputy-head of British Security Coordination in New York, the massive British covert influence operation to make the United States join the war.

In 1941 Ellis became head of its Washington office. In the period before Pearl Harbor, Ellis briefed J Edgar Hoover in counter-espionage techniques. He provided the blueprint from which William J. Donovan was able to set up the Office of Strategic Services and consequently was awarded the American Legion of Merit.[6]

At the end of the War he was appointed a CBE for his work.[2]

Double cross allegations

In 1945, the SIS learned from captured Nazi spy controller Walter Schellenberg that a man named Ellis had betrayed the organisation. However, it failed to act[4] and Pincher believes that Ellis was subsequently blackmailed into spying for the Soviets.[7]

Ellis was subsequently sent to Singapore on the staff of the United Kingdom Commissioner-General for South-East Asia.[6] He was 'controller Western Hemisphere' and 'controller Far East' during the early 1950s.[4] Ellis also helped set up the Australian Secret (Intelligence) Service.[1] He retired in 1953 and was awarded the CMG.[2]

A lengthy investigation into the allegations against Ellis was code-named "Emerton".[4] A former in-house CIA historian, Thomas F. Troy, stated that James Angleton had warned him in 1963 that Ellis was under investigation as a suspected Soviet agent.[8] Pincher alleged that in 1965 Ellis was challenged and admitted to spying for Germany.[7] The Independent's James Dalrymple said that Ellis 'sold "vast quantities of information" about the British secret service to the Germans', aiding the production of the Gestapo handbook for the Invasion of Britain.[9]

Ernest Cuneo, who worked for Ellis during the Second World War argues: "If the charge against Ellis is true... it would mean that the OSS, and to some extent its successor, the CIA, in effect was a branch of the Soviet KGB".[3]

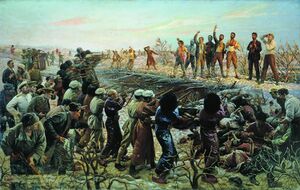

Malleson mission

In retirement C. H. Ellis wrote a book about the Malleson mission: The Transcaspian Episode. Among the incidents addressed in the book was the execution of 26 Commissars – including Stepan Shahumyan – of a Soviet client, the Centrocaspian Dictatorship, in September 1918.[10] The commissars had earlier fled the Mussavatist Azerbaijan advanced guard in the September Days of 1918 just before the Turks occupied Baku. They planned to sail to Astrakhan, the only Caspian port still in Bolshevik hands but were instead dumped at the port of Krasnovodsk where they were summarily executed by the local Menshevik garrison. Ellis fundamentally disagreed with claims by the Socialist Revolutionary journalist Vadim Chaikin that British officers (including himself) were responsible for the deaths of the Commisars, pointing out that it had been a triumph for Soviet propaganda.[6] after the incident became known. In a letter to The Times in 1961, Ellis placed the blame with the "Menshevik-Socialist Revolutionary" Transcaspian Government, which had jurisdiction over the prisoners. According to Ellis the claim of British involvement arose only after the Socialist Revolutionaries found the need to ingratiate themselves with the stronger Bolsheviks.[11]

References

- Ellis, C. H, "The British Intervention in Transcaspia 1918–1919" University of California Press, 1963

- James Cotton, ‘”The Standard Work in English on the League” and Its Authorship: Charles Howard Ellis, an Unlikely Australian Internationalist’, History of European Ideas, 42:8, 1089-1104, 2016 DOI: 10.1080/01916599.2016.1182568

References

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c Cain, Frank, 'Ellis, Charles Howard (Dick) (1895–1975)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c Mr C. H. Ellis (Obituaries) The Times 16 July 1975.

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c http://spartacus-educational.com/SPYellisCH.htm

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c d e Nigel West, ELLIS, DICK, Dictionary of British Intelligence.

- ↑ James Cotton,‘”The Standard Work in English on the League” and Its Authorship'

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c "Mr C. H. Ellis", H. M. H., The Times, 21 July 1975

- ↑ Jump up to: a b Chapman Pincher, Letters:"Security risks", The Times, 6 May 1981

- ↑ Lycett, Andrew. Untold tales; Books, The Times, 6 June 1996

- ↑ Dalrymple, James. Fatherland UK... The Independent 3 March 2000

- ↑ Macintyre, Ben. Massacre that was a triumph for the Soviet propaganda machine, The Times, 11 February 2012

- ↑ C. H. ELLIS, Letters:Baku Commissars, The Times, 10 October 1961