Anglo-French Agreement of 23 December 1917

| |

| Description | A 1917 Anglo-French conspiracy for a dismemberment of Russia after the October Revolution. |

|---|---|

| Perpetrators | Britain, France |

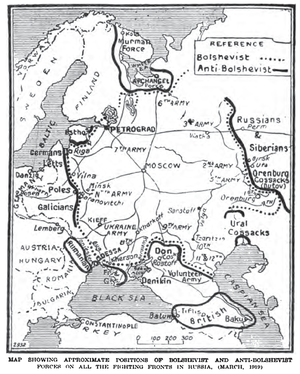

The Anglo-French Agreement of 23 December 1917 was a British-French agreement on joint intervention in Soviet Russia and its division into spheres of influence, effectively to bring about the complete dismemberment of the Russian empire for their own political and commercial advantage,[1]; an opportunistic land grab when Russia was at its weakest.

The move was a continuation of the Great Game, where Great Britain during the 19th century had feared the rising power of Russia as manifested in the Russian penetration of Central Asia and in Russian expansion in the Far East. France, on the other hand, looked for economic advantages (coal, grain) where Great Britain mainly pursued a political aim, although the British had their eyes especially on the Caucasus oil.

Official narrative

The military intervention in the Russian civil war is sort of mentioned in offical history. But the partition plan of a former ally is a third rail subject, especially since it failed after the Bolsheviks consolidated power.

Background

In March 14, 1917, the Petrograd Soviet called on units to elect a committee which would run the unit and specifically refused officers access to weapons, something which destroyed the organization and discipline of the Russian Army. Most of the military specialists in the allied countries began to doubt the effectiveness of the Russian revolution in so far as it would affect an Entente victory over the Central Powers. Later, when the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government in November, 1917, Russia was obviously no longer any help to the Allies, and not only military specialists but also political leaders lost faith in Russia as an effective ally.[1]

In these circumstances the allied governments were ready to undertake open military intervention in Russia to continue the war against Germany; this is the reason given to officially explain and justify the policy of the Allies.

But there was another reason for this intervention, a reason that has existed all through the nineteenth century. Great Britain's fear of the rising power of Russia as manifested in the Russian penetration of Central Asia and in Russian expansion in the Far East. France, on the other hand, looked for material economic advantages where Great Britain mainly pursued a political aim. France and Great Britain came to an understanding and agreed to an actual dismemberment of Russia.[1] Britain would gain what late became the Baltic states and the oil producing regions of Baku and Transcaucasia; France would get the vast coal resources of Donbas, the Ukrainian grain, and the naval base of Sevastopol on Crimea.[1]

General Denikin, the leader of the White armies, relates that he received confirmation of this agreement from the French representative, Colonel Corbeil, in a letter of May 27, 1919, and that "the line dividing the zones was drawn from the Bosporus through the Straits of Kertch to the mouth of the River Don and further along the Don up to Tsaritsin, leaving to the east the English zone of action and to the west - the French." He continues: "This strange line had no reason whatsoever from the strategic point of view, taking in no consideration of the Southern operation directions to Moscow nor the idea of unity of command. Also, in dividing into halves the land of the Don Cossacks, it did not correspond to the possibilities of a rational supplying of the southern armies and satisfied rather the interests of occupation and exploitation than those of a strategic covering and help."[1]

The agreement

Convention between France and England on the subject of activity in Southern Russia.

1. The activity directed by France is to be developed north of the Black Sea (against the enemy). The activity directed by England is to be developed southeast of the Black Sea (against the Turks). 2. Whereas General Alexeev at Novocherkassk has proposed the execution of a program envisaging the organization of an army intended to operate against the enemy, and whereas France has adopted that program and allocated a credit of $100,000,000 for this purpose and made provision for the organization of interallied control, the execution of the program shall be continued until new arrangements are made in concert with England. 3. With this reservation, the zones of influence assigned to each government shall be as follows:The English zone: The Cossack territories, the territory of the Caucasus, Armenia, Georgia, Kurdistan. The French zone: Bessarabia, the Ukraine, the Crimea.

4. The expenses shall be pooled and regulated by a centralizing interallied organ.[2]

Bessarabia, the Ukraine and the Crimea are large granaries, while the western part of the Don territories, which had been assigned to France, comprises the famous coal region of the Donetsk, worthless to England but of great importance to France. England in turn obtained all the Russian oil fields in the Caucasus.

France also made a treaty with General Wrangel, as the head of the South Russian Government, who agreed to the following conditions, which would have made Russia an economic puppet of France.

1. To recognize all the obligations of Russia and of her towns toward France with priority and the payment of interest on interest.

2. France converts all the Russian debts into a new 6% per cent loan, with partial yearly liquidation during thirty-five years.

3. The payment of interest and the yearly liquidation is guaranteed by (a) the transfer to France of the right of exploitation of all railways in European Russia during a certain period; (b) the transfer to France of the right to oversee custom and port duties in all the ports of the Black Sea and Azov Seas; (c) putting at the disposal of France all the surplus of grain in the Ukraine and the Kuban territories; (d) putting at the disposal of France three quarters of the output of oil; (e) the transfer to France of one-fourth of all the coal of the Donetz output during a certain period of years. The periods of time mentioned will be fixed by a special agreement.[1]

Military moves

The first British soldiers landed in Russia’s northern ports in the spring of 1918, immediately after the conclusion of a peace treaty between the Germans and the Bolsheviks at Brest-Litovsk on March 3. The troops also made incursions into the south of the country, in Transcaucasia, in Central Asia and in the Far East.[3]

The agreement formed the basis for the further allied interventions in Russia, which ultimately involved several hundred thousand soldiers, until they eventually withdrew over the next few years.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c d e f Leonid I. Strakhovsky The Franco-British Plot to Dismember Russia https://www.jstor.org/stable/45333645

- ↑ Leonid I. Strakhovsky The Franco-British Plot to Dismember Russia https://www.jstor.org/stable/45333645 who has it from "the annex of Louis Fischer's The Soviets in World Affairs"

- ↑ https://www.rbth.com/history/334043-why-did-british-troops-attack-russia