Nelson Mandela/Lockerbie involvement

Pan Am Flight 103's highest profile victim: UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson | |

| Nelson Mandela was closely involved in resolving the long-running dispute between Britain and America who accused Libya of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, in the bringing to trial in 2000 of the two indicted Libyans and in efforts subsequently to have Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's conviction overturned. |

Nelson Mandela was closely involved in resolving the long-running dispute between Britain and America who accused Libya of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, in the bringing to trial in 2000 of the two indicted Libyans and in efforts subsequently to have Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's conviction overturned.[1]

According to Dr John Cameron:

- "Nelson Mandela decided to look at the evidence because he said there was a big problem with the forensic and that this was a miscarriage of justice. Mandela was a lawyer. He approached the Scottish Church and asked them to look into this, and I wrote a 4000-word report." Extract from Al Jazeera film ‘Lockerbie: The Pan Am Bomber?’ (20’25’’)

Contents

Perfect alibi for Lockerbie

- Full article: Pan Am Flight 103

- Full article: Pan Am Flight 103

In August 1988, Nelson Mandela was admitted to a luxury Cape Town clinic after contracting tuberculosis in Pollsmoor prison. On 7 December 1988, the Minister of Justice Kobie Coetsee announced that, following Mandela's complete recovery, he had been transferred to a "suitable, comfortable and properly secured home" adjacent to Victor Verster prison near the town of Paarl, some 30 miles from Cape Town. It was a four-bedroom house of his own, complete with a swimming pool and shaded by fir trees, where he could receive visitors as he pleased, including his wife Winnie.[2]

Thus, when Pan Am Flight 103 was sabotaged over Lockerbie in Scotland on 21 December 1988, the African National Congress (ANC) leader remained in custody as a prisoner. Despite this perfect alibi, the apartheid regime were quick to accuse Nelson Mandela and the ANC of masterminding the Lockerbie bombing.

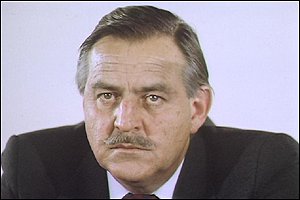

This amazing accusation was made on 11 January 1989 by South African Foreign Minister Pik Botha who had travelled to Stockholm in Sweden with other foreign dignitaries – including UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar – to attend the memorial service of United Nations Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, the highest profile victim of the 270 fatalities at Lockerbie.[3]

Interviewed by Sue MacGregor on BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme, Pik Botha alleged that he and a 22-strong South African delegation, who were booked to fly from London to New York on 21 December 1988, had been targeted by the ANC.[4] However, having been alerted to these ANC plans to kill him, Pik Botha said he managed to outsmart them by taking the earlier Pan Am Flight 101 from Heathrow to JFK.[5]

Mandela's Lockerbie statement

On 21 January 1992, nearly two years after his release from prison, Mandela issued the following statement on Lockerbie:

"The ANC has consistently condemned all acts of "terrorism". The Lockerbie disaster was a tragic incident which resulted in the unfortunate loss of innocent lives. The ANC once again takes the opportunity to express deepfelt sympathy to the families of the deceased. It is in the interest of peace, stability and security that if there is clear evidence of the involvement of identified suspects they should be arrested and punished as soon as possible. In the present climate of suspicion and fear it is important that the trial should not be intended to humiliate a head of state. It should not only be fair and just, but must be seen to be fair and just. This must be in the context of respect for the sovereignty of all countries.

The ANC believes that if the above objectives are to be achieved, the following options should be considered:

- If no extradition treaty exists between the countries concerned, the trial must be conducted in the country where the accused were arrested;

- The trial should be conducted in a neutral country by independent judges;

- The trial should be conducted at The Hague by an international court of justice.

We urge the countries concerned to show statesmanship and leadership. This will ensure that the decade of the Nineties will be free of confrontation and conflict."[6]

1992 Mediation proposal

Early in 1992, two years before the end of apartheid, Nelson Mandela made an informal approach to US President George H W Bush with a proposal to have the two accused Libyans tried in a neutral country and by independent judges. Although Bush reacted favourably to the proposal – as did President François Mitterrand of France and King Juan Carlos I of Spain – UK Prime Minister John Major flatly rejected Mandela’s plan for the Lockerbie trial.

Enter Prof Black

Robert Black, Emeritus Professor of Scots Law at Edinburgh University, intervened in the negotiations to bring the two accused to trial following the blueprint set out by Nelson Mandela. Black explained:[7]

"I first became involved in the Lockerbie affair in January 1993. I was approached by representatives of a group of British businessmen whose desire to participate in major engineering works in Libya was being impeded by the UN sanctions. They had approached the then Dean of the Faculty of Advocates (the head of the Scottish Bar) and asked him if any of its members might be willing to provide advice to them - on an unpaid basis! - on Scottish criminal law and procedure in their attempts to unblock the logjam. The Dean of Faculty, Alan Johnston QC (later Court of Session judge Lord Johnston), recommended me. The businessmen asked if I would be prepared to provide independent advice to the government of Libya - again on an unpaid basis - on matters of Scottish criminal law, procedure and evidence with a view (it was hoped) to persuading them that their two citizens would obtain a fair trial if they were to surrender themselves to the Scottish authorities. There was, of course, never the slightest chance that surrender for trial in the United States could be contemplated by the Libyans, amongst other reasons because of the existence there of the death penalty for murder."

Since Lord Johnston died on 14 June 2008, we only have Prof Black’s word that it was Lord Johnston who recommended him to the 'group of British businessmen' whom Black has resolutely refused to identify.

Enter Tiny Rowland

In fact, the mystery group was none other than Lonrho plc, whose chief executive Tiny Rowland (allegedly an MI6 agent) head-hunted that other asset of British intelligence, Professor Robert Black.[8] Lonrho's Sir John Leahy – former ambassador to South Africa – supported Prof Black in his primary task which was to cover-up the targeting by apartheid South Africa’s regime of Lockerbie’s highest profile victim: UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson.[9] Tiny Rowland went on to finance the 1994 documentary The Maltese Double Cross in which he made the amazing claim that a 23-strong South African delegation - including foreign minister Pik Botha - were booked on Pan Am Flight 103 of 21 December 1988 but had been given a "warning from a source which could not be ignored" and changed flights. Rowland's claim was later proved to be false: Pik Botha and his delegation had always been booked on the earlier Pan Am Flight 101 to New York for their attendance at the signing ceremony of Namibia's independence agreement at United Nations headquarters in New York on 22 December 1988.[10]

Back to Black

Professor Black’s other important task was to frustrate Nelson Mandela’s plans in relation to bringing to trial the two Libyans who had been indicted in November 1991 and were accused of carrying out the Lockerbie bombing. Thus, in October 1993, seven months before Nelson Mandela’s government took over from the apartheid South African regime, Prof Black attended a meeting in Tripoli of an international team of lawyers representing the two accused Libyans, Fhimah and Megrahi. This team consisted of lawyers from Scotland, England, Malta, Switzerland and the United States and was chaired by the principal Libyan lawyer for the accused, Dr Ibrahim Legwell. A press release issued at the conclusion of the meeting indicated that the accused were not prepared to surrender themselves for trial in either Scotland or the United States. It subsequently transpired that the primary reason for this was their belief that, because of unprecedented pre-trial publicity over the years, neither a Scottish nor an American jury could possibly bring to their consideration of the evidence the degree of impartiality and open-mindedness that accused persons are entitled to expect and that a fair trial demands. The attitude of the Libyan Government was that it was satisfied (in part due to the information and advice supplied to it by Prof Black regarding the Scottish law of criminal evidence and procedure) that its citizens would obtain a fair trial in Scotland, but that it had no constitutional authority to hand them over to the Scottish authorities. The question of voluntary surrender for trial was one for the accused and their legal advisers, and while the Libyan Government would place no obstacles in the path of, and indeed would welcome, such a course of action, there was nothing that it could lawfully do to achieve it.[11]

Back to Tripoli

On 10 January 1994, four months before Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as President of South Africa, Prof Black visited Tripoli for a second time and, in a letter to Dr Legwell, suggested a means of resolving the impasse created by the insistence of the Governments of the United Kingdom and United States that the accused be surrendered for trial in Scotland or America and the adamant refusal of the accused to submit themselves to trial by jury in either of these countries. The proposal embodied the following five elements:

- That a trial be held outwith Scotland (perhaps in the premises of the International Court of Justice at The Hague) in which the governing law and procedure would be the law and procedure followed in Scottish criminal courts in trials on indictment.

- That the prosecution in the trial be conducted by the Scottish public prosecutor, the Lord Advocate, or his authorised representative.

- That the defence of the accused be conducted by independent Scottish solicitors and counsel appointed by the accused.

- That the jury of fifteen persons which is a feature of Scottish criminal procedure on indictment be replaced by an international panel of five judges presided over and chaired by a judge of the Scottish High Court of Justiciary whose responsibility it would be to direct the panel on Scottish law and procedure.²

- That any appeals against conviction or sentence be heard and determined in Scotland by the High Court of Justiciary in its capacity as the Scottish Court of Criminal Appeal.

Although not expressly stated in the proposal, it was the clear implication of its provisions that, in the event of the accused being convicted by the Court, they would serve any sentence of imprisonment imposed upon them in a prison in Scotland. In a letter to Prof Black dated 12 January 1994, Dr Legwell stated that this scheme was wholly acceptable to his clients, and if it were implemented by the Government of the United Kingdom the suspects would voluntarily surrender themselves for trial before a tribunal so constituted. By a letter of the same date the Deputy Foreign Minister of Libya stated that his Government would place no obstacle in the path of its two citizens should they elect to submit to trial under this scheme.[12]

Mediation by President Mandela

On 29 May 1994 – less than three weeks after becoming President – Nelson Mandela wrote to John Major urging a resolution of the Lockerbie case:

- Mandela plea to Major on Lockerbie trial

- The South African president, Nelson Mandela, has written to John Major to urge a resolution of the conflict with Libya over the Lockerbie bombing, arguing that the continuing dispute is damaging relations among all African nations.

- News that Mr Mandela and the Prime Minister have debated the issue is a vindication for those who have long argued that the Lockerbie stalemate has implications beyond bringing those responsible to justice.

- A letter from the South African president to Downing Street and Mr Major's response, copies of which have been obtained by The Scotsman, show clearly that Lockerbie and the sanctions imposed to try to persuade Libya to hand over the two official suspects has been a regular topic for discussion between the two men.

- Libya has been largely economically isolated since it refused to hand over the men Britain and the US accuse of blowing up Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie with the loss of 270 lives in December 1988.

- Mr Mandela writes: "The reason I raise the matter again is because of the damaging effect prolongation of the impasse is having on relations in Africa both within the Organisation of African Unity context and bilateral relations. In my meetings with African leaders invariably the matter comes up and there is the sense that an urgent solution should be sought."

- Mr Mandela goes on to urge Mr Major to re-consider his opposition to a trial in a neutral country "in the interest not only of Libya but of the continent, the Muslim world and international conciliation."

- However, Mr Major remains firm in his view that to accede to a trial under Scottish jurisdiction at The Hague, for example, would achieve nothing in terms of removing the possibility of prejudicial media coverage and, more importantly, would only set a dangerous precedent.

- He writes: "You can well imagine the sensitivity of asking the British Parliament to approve a law which would be interpreted by many as acceptance that a trial in Scotland would not be fair and as a concession to alleged terrorists."

- Mr Major finishes by urging Mr Mandela to use his influence with the Libyan leader, Colonel Gaddafi, to persuade him that accepting a trial in Scotland or the US is the only solution to the problem.

- The Linlithgow MP, Tam Dalyell, who has long campaigned for a resolution of the conflict with Libya over Lockerbie, said: "The fact that President Mandela...should take the trouble to write one of his rare letters to the British Prime Minister about this is an indication of the importance he attaches to this issue, which is Africa-wide."[13]

In November 1994, President Mandela formally offered South Africa as a neutral venue for the Lockerbie trial but this was again rejected by Prime Minister, John Major, who said that the British government did not have confidence in foreign courts. Prof Black’s views on Mandela's proposal for South Africa to host the Lockerbie trial are not known but, presumably, he was strongly opposed since the apartheid regime’s role in the Pan Am bombing would undoubtedly have come to light as a result of a South African trial. A further three years elapsed until Mandela's offer was repeated to Major's successor, Tony Blair, when President Mandela visited London in July 1997 and again at the 1997 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Edinburgh between 24 and 27 October 1997. At the latter meeting, Mandela warned that "no one nation should be complainant, prosecutor and judge" in the Lockerbie case. Immediately before attending CHOGM, Mandela paid his first visit as President to Colonel Gaddafi in Libya, and visited Gaddafi again on 29 October 1997 which prompted speculation that Mandela was trying to mediate an end to the UN sanctions imposed on Libya over Lockerbie.[14]

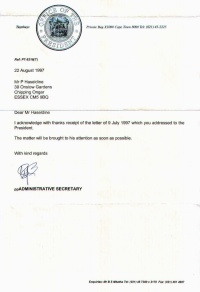

Patrick Haseldine's intervention

On 9 July 1997, former British diplomat Patrick Haseldine faxed a letter to His Excellency President Nelson Mandela (c/o the South African High Commission in London, Fax: 0171 451 7284):

- Dear Mr President,

- Lockerbie bombing and my dismissal from HM Diplomatic Service

- For writing to The Guardian newspaper on 7th December 1988 accusing the apartheid régime of state-sponsored "terrorism", I was immediately suspended from the Diplomatic Service.

- Solicitor Geoffrey Bindman wrote supporting me to The Guardian a week later - Shabby manouevres that aid and abet Botha (copy follows) - but to no avail. I was sacked eight months later.

- With the recent change of government in Britain, I applied to the new Foreign Secretary for reinstatement in the Diplomatic Service. Robin Cook replied on 16th May 1997 (copy follows) turning down my application because of elapsed time: "It is now a decade since your dismissal."

- If you have a moment during your forthcoming discussions with Prime Minister Blair, I should be very grateful if you would put in a word on my behalf. I am sure that Mr Blair will respond positively to such an approach, if not by reinstating me then by compensating me for loss of earnings and for full pension rights.

- You will no doubt also raise the Lockerbie question with Mr Blair (in which connection please see my letter of 15th January 1997 to High Commissioner Mr Msimang - copy follows). On the eve of your arrival in the UK, The Guardian reported that Germany has reopened its investigation into the Lockerbie bombing (copy follows). Since the "forensic" evidence against the two Libyans appears to be totally discredited by the information given to the Germans, I believe that the UK should now mount a judicial inquiry (perhaps under Sir Richard Scott) into Lockerbie. You may wish to persuade Mr Blair of the need for a rigorous inquiry into all aspects of the case.

- I remain convinced that state-sponsored South African "terrorism" was responsible both for the sabotage of Pan Am 103 and the crash which killed President Machel.

- Yours sincerely,

Parliamentary debate

On 7 November 1997, Labour MP Tam Dalyell began a House of Commons debate by revealing the influence of both British tycoon Tiny Rowland and Professor Robert Black in the context of arranging a venue for the Lockerbie trial:[15]

"For the past 30 years, Nelson Mandela has been something of an icon for the left. His prestige for what he has done is absolutely unquestioned; therefore, surely, it behoves us to listen to what he says on what might be an awkward subject. The connection goes back to the time when Nelson Mandela wrote what I think was his only letter to the right hon. Member for Huntingdon (Mr Major) as Prime Minister, which was about Lockerbie. I do not hide from anyone the fact that I was given a copy by Tiny Rowland. When there was a change of Government, the first meeting Mr Mandela had with my right hon. Friend the Prime Minister lasted an hour and, at Mr Mandela's insistence, 40 minutes of it was taken up with Lockerbie. Mr Mandela then came to the Commonwealth Heads of Government conference in Edinburgh and made a much publicised statement saying that in his considered judgment no country should be claimant, prosecutor and judge in the same case and in a situation such as Lockerbie. That was his view and I do not think that I distort it. It was his opinion – tactfully expressed – that we should take seriously the idea of a trial in a third, neutral country. Indeed, that has been the view of South Africa, to whose personnel I have spoken, and of many other countries for a long time. The purpose of this debate is to go through – I hope without distortion – the objections to such a course of action and then to try to refute them. I believe in being totally candid with the House of Commons: I am not a lawyer, so I have taken advice. That advice comes predominantly from Professor Robert Black QC, professor of Scots Law in the University of Edinburgh. One of the tasks to which the Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, my hon. Friend the Member for Manchester, Central (Mr Lloyd), must address himself is to say why the Government lawyers believe that their opinion is superior to that of the Queen's Counsel who is professor of Scots Law in the University of Edinburgh."

Press release by Professor Black

On 23 April 1998, this message was sent to Safia Aoude by Prof Black, who had participated in the journey to Libya and Egypt together with Dr Jim Swire.

Lockerbie

A meeting to discuss issues arising out of the Lockerbie bombing was held in the premises of the Libyan Foreign Office in Tripoli on the evening of Saturday 18 April 1998. Present were Mr Abdul Ati Obeidi, Under-Secretary of the Libyan Foreign Office; Mr Mohammed Belqassem Zuwiy, Secretary of Justice of Libya; Mr Abuzaid Omar Dorda, Permanent Representative of Libya to the United Nations; Dr Ibrahim Legwell, head of the defence team representing the two Libyan citizens suspected of the bombing; Dr Jim Swire, spokesman for the British relatives group UK Families-Flight 103; and Professor Robert Black QC, Professor of Scots Law in the University of Edinburgh and currently a visiting professor in the Faculty of Law of the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

At the meeting, discussion focused upon the plan which had been formulated in January 1994 by Professor Black for the establishment of a court to try the suspects which would: operate under the criminal law and procedure of Scotland; have in place of a jury an international panel of judges presided over by a senior Scottish judge; and, sit not in Scotland but in a neutral country such as The Netherlands.

Among the issues discussed were possible methods of appointment of the international panel of judges, and possible arrangements for the transfer of the suspects from Libya for trial and for ensuring their safety and security pending and during the trial.

Dr Legwell confirmed, as he had previously done in January 1994, that his clients agreed to stand trial before such a court if it were established. The representatives of the Libyan Government stated, as they had done in 1994 and on numerous occasions since then, that they would welcome the setting up of such a court and that if it were instituted they would permit their two citizens to stand trial before it and would co-operate in facilitating arrangements for that purpose.

Dr Swire and Prof Black undertook to persist in their efforts to persuade the Government of the United Kingdom to join Libya in accepting this proposal.

On Sunday 19 April 1998, Prof Black met the South African ambassador to Libya and Tunisia, His Excellency Ebrahim M Saley, and discussed with him current developments regarding the Lockerbie bombing. He also took the opportunity to inform the ambassador of how much President Mandela's comments on the Lockerbie affair at the time of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in October 1997 in Edinburgh had been appreciated.

On Monday 20 April 1998, Dr Swire and Professor Black had a meeting lasting some 40 minutes with the Leader of the Revolution, Muammar Gaddafi. Also present were the Libyan Foreign Secretary, Mr Omar Ali Montasser, and Mr Dorda. The Leader was informed of the substance of the discussions held on Saturday 18 April 1998, and expressed his full support for the conclusions reached.

Prof Black has now returned to South Africa and can be contacted at the e-mail address appearing above, or by telephone on 083 731 8859 [End of message].[16]

Breaking the logjam

According to Paul Foot's article "Lockerbie: the Flight from Justice", Nelson Mandela was irritated by the continued sanctions on Libya. He was friendly with Colonel Gaddafi, who had contributed generously to the African National Congress, Mandela’s party, when it was engaged in illegal and armed opposition to the apartheid regime.

President Mandela firmly believed that Libya was being singled out for special hostility by the United States and, in the case of Lockerbie, he regarded the treatment of Libya as unfounded and unfair. To the intense irritation of the US State Department, Mandela launched a diplomatic offensive to persuade Gaddafi to release the two accused Libyan men for trial by Scottish judges in Europe.

President Mandela chose as his chief negotiator and plenipotentiary his most trusted adviser and confidant, the secretary to the South African Cabinet and head of the country’s civil service, Professor Jakes Gerwel, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Western Cape. Mandela also persuaded Prince Bandar bin Sultan of Saudi Arabia to take part in the negotiations with Gaddafi. The Prince and the Cabinet Secretary, Mandela knew, were trusted by the Libyan president as much as anyone else in the world.

The negotiations went on for a year until 5 April 1999 when the two suspects (Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah), finally gave themselves up for trial by Scottish judges under Scottish law (with one exception: everyone agreed that the men should be tried without a jury).[17]

Blackout of Mandela blueprint

Patrick Haseldine has claimed that Professor Robert Black QC was recruited by South African intelligence and financed by Tiny Rowland to frustrate Nelson Mandela’s plans for Lockerbie justice. He notes that Black:[18]

- ensured that the Lockerbie trial was not held in a neutral country. Instead, he arranged for the Lockerbie Trial to be conducted from May 2000 to January 2001 at Camp Zeist, a former US Air Force base in the Netherlands which, for the duration of the trial, became British territory;

- decreed that Scotland’s Crown Office would be the ‘complainant’ at the trial;

- arranged for Scotland’s Lord Advocate (Colin Boyd) to be the ‘prosecutor’ at the trial; and,

- insisted that – instead of ‘independent judges’ at the trial – all four Judges Lords Sutherland, Coulsfield and MacLean (Lord Abernethy as an alternate) had to be from Scotland.

Although one of the two accused Libyans was found not guilty, it was thanks to Professor Black that the other Libyan, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, was found guilty.[19]

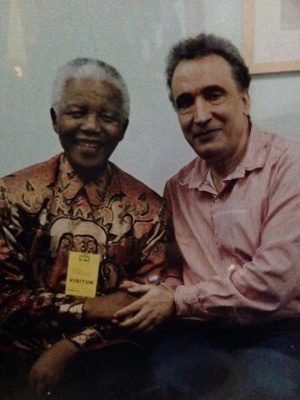

Mandela visits Megrahi

On 10 June 2002, Nelson Mandela visited Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for more than an hour at Barlinnie Jail in Glasgow. Megrahi described the meeting thus:

- "Three months after my transfer to Barlinnie, Nelson Mandela kept his promise to visit me. That the world’s most respected statesman should again take the trouble to demonstrate his solidarity gave me a great lift. We chatted for sometime, mainly about the unjust guilty verdict. Having spent 27 years imprisoned on Robben Island, the agonies of prison life were etched into his soul. He asked me about my living conditions, the standard of my food and my bed, clearly aware of the huge importance of those things to a prisoner’s well-being. Before he left I introduced him again to my family, who thanked him and presented him with a bouquet of flowers. I was allowed to take photographs of him in the reception area and he signed my Arabic version of his book 'Long Walk to Freedom', which describes his prison years. In it he wrote:

- 'To Comrade Megrahi, Best wishes to one who is in our thoughts and prayers continuously. Mandela'."[20]

Following the meeting which took place in Megrahi's own cell within the prison, in a section nicknamed by other inmates as "Gaddafi's Cafe", Mandela held a 30-minute press conference and called for a fresh appeal in the case.

- "Megrahi is all alone," Mandela said. "He has nobody he can talk to. It is a psychological persecution that a man must stay for the length of his long sentence all alone." He added that al-Megrahi was being "harassed" by other inmates at Barlinnie. "He says he is being treated well by the officials but when he takes exercise he has been harassed by a number of prisoners," said Mr Mandela. "He cannot identify them because they shout at him from their cells through the windows and sometimes it is difficult even for the officials to know from which quarter the shouting occurs."

Mandela continued:

- "It would be fair if Mr Megrahi was transferred to a Muslim country - and there are Muslim countries which are trusted by the West. It will make it easier for his family to visit him if he is in a place like the Kingdom of Morocco, Tunisia or Egypt."

Mandela described in detail how a four-judge commission from the Organisation of African Unity had criticised the basis by which Megrahi came to be convicted at a special Scottish court, sitting at Camp Zeist in the Netherlands in 2001:

- "They have criticised it fiercely, and it will be a pity if no court reviews the case itself. From the point of view of fundamental principles of natural law, it would be fair if he is given a chance to appeal either to the Privy Council or the European Court of Human Rights."

Concluding his remarks, Nelson Mandela said he also hoped to meet Prime Minister Tony Blair and US President George Bush to discuss the Megrahi case.[21][22]

References

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Mandela and Dr John Cameron's report"

- ↑ "Opening Pandora’s Apartheid Box - Part 29 – Secret talks with the Enemy"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Bernt Carlsson's secret meeting in London"

- ↑ "The Reunion: Sue MacGregor reunites a group of people intimately involved in Nelson Mandela's release"

- ↑ "ANC as the fall-guys for Lockerbie bombing" Patrick Haseldine's letter to The Guardian, 22 April 1992

- ↑ "Nelson Mandela's statement on the Lockerbie disaster" 21 January 1992

- ↑ "Al-Megrahi defence knew bomb fragment was sent to US"

- ↑ "Tiny Rowland: Portrait of the Bastard as a Rebel"

- ↑ "Bernt Carlsson: Assassinated on Pan Am Flight 103"

- ↑ "Why the Lockerbie flight booking subterfuge, Mr Botha?"

- ↑ "Blackout over Lockerbie"

- ↑ "TheLockerbieTrial.Com" Archive of Professor Black and Ian Ferguson website

- ↑ "Mandela plea to Major on Lockerbie trial" by Christopher Cairns, The Scotsman, 29 May 1994

- ↑ "Mandela's visit to Libya to discuss Lockerbie affair"

- ↑ "Hansard, 7 November 1997"

- ↑ Press release from Prof Robert Black" 23 April 1998

- ↑ "Lockerbie - The Flight From Justice" Paul Foot, Private Eye Special Report

- ↑ "Tiny Rowland, Lonmin and Lockerbie"

- ↑ "Blackout of Mandela Blueprint for Lockerbie Justice"

- ↑ "Nelson Mandela’s message to Megrahi"

- ↑ "Mandela meets Lockerbie bomber"

- ↑ "Mandela appeals on behalf of Lockerbie bomber"