Geoffrey Bindman

(human rights lawyer) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Geoffrey Lionel Bindman 3 January 1933 |

| Alma mater | Oriel College (Oxford) |

Sir Geoffrey Bindman QC (born 3 January 1933)[1] is a British solicitor specialising in human rights law, and founder of the human rights law firm Bindmans LLP, described by The Times as "never far from the headlines."

He has been Chair[2] of the British Institute of Human Rights since 2005.[3] He won The Law Society Gazette Centenary Award for Human Rights in 2003,[4] and was knighted in 2006 for services to human rights.[5]

In 2011 Sir Geoffrey Bindman was appointed Queen's Counsel.[6]

Contents

Family and early professional life

Bindman was born and brought up in Newcastle upon Tyne to a family descended from Jewish immigrants. His father Gerald [1904-1974] was a GP who married Rachael Lena Doberman in 1929. Bindman attended the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle, and then graduated from Oriel College (Oxford), with a Bachelor of Civil Law in 1956, qualifying as a solicitor three years later. He became a legal advisor to the Race Relations Board in 1966, a job he retained for seventeen years. He also served as a legal advisor to Amnesty International and represented satirical magazine Private Eye.[7] In the late 1980s, Bindman visited South Africa as part of an International Commission of Jurists delegation sent to investigate apartheid[8] and subsequently became editor of a book on the topic, South Africa and the Rule of Law.[9]

Bindmans LLP

In 1974, Geoffrey Bindman established Bindmans LLP as a firm with the aim of "protecting the rights and freedoms of ordinary people."[10] Since then, he has personally acted as lawyer for numerous high-profile people including James Hanratty,[11] Keith Vaz[12] and Jack Straw.[13] Bindman also continued his international human rights work, acting as a United Nations observer at the first democratic election in South Africa in 1994[14] and representing Amnesty International's interests in Augusto Pinochet's arrest and trial in the late 1990s.[15]

In December 2006, Bindman signed a petition calling on Prime Minister Tony Blair to compensate and substantially increase the FCO pension of British diplomat, Patrick Haseldine, whose Article 10 right to "freedom of expression" was breached when he was sacked for writing a letter to The Guardian 18 years earlier. The petition was unsuccessful.[16]

In September 2012, Bindman told BBC Radio 4 he agreed with Desmond Tutu that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair should be prosecuted on the grounds that starting the Iraq War was a "crime of aggression" in breach of the United Nations Charter.[17]

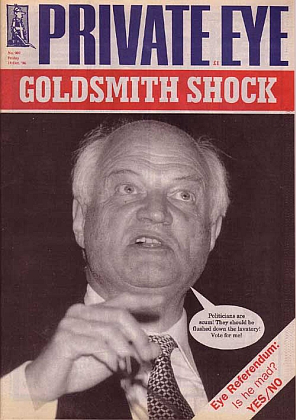

Goldenballs

In November 2007, Sir Geoffrey Bindman wrote an article in the New Law Journal about efforts by Sir James Goldsmith to put Private Eye magazine out of business. Buccaneering businessman Tiny Rowland helped fund the legal defence of Private Eye against Goldsmith's libel writs, as detailed in Richard Ingrams' book "Goldenballs"!

Lord Gnome, the legendary proprietor of Private Eye, frequently required the services of his solicitors Messrs Sue, Grabbit and Runne. I was lucky enough to occupy that role for the real life editor, Richard Ingrams, for some 15 years in the 1970s and 1980s. A highlight of the period was the prolonged litigation between the magazine and the late billionaire entrepreneur Sir James Goldsmith. In 1976 Goldsmith attracted the interest of Private Eye. One of its stories linked him, through his solicitor Eric Levine, to the criminally convicted former leader of Newcastle City Council, T Dan Smith, and another to some alleged skullduggery involving the well known City finance house of the day, Slater Walker. A third claimed that Goldsmith had attended a lunch for friends of Lord Lucan, who had recently disappeared following the murder of his children’s nanny. Private Eye suggested that Lucan’s friends had met to discuss how they could help him to escape the clutches of the law. However, it later emerged that Goldsmith had been absent on this occasion.

Avalanche of writs

Goldsmith was angry, as well as rich. He set out to destroy the little magazine that had presumed to offend him. He sued over all three stories. But he spread the net far beyond Private Eye. In a novel exercise in overkill, he issued separate writs against all the distributors and wholesalers of the magazine. There were over 60 writs. Private Eye faced a huge financial burden. It was liable to indemnify all those whom Goldsmith had chosen to sue.

The first task was to reassure the recipients of these writs that the indemnity would be honoured. Private Eye lacked the resources but had a lot of supporters. A drive to raise money began, inspirationally named the "Goldenballs Fund".

The next imperative was to challenge the proliferation of writs as an abuse of the legal process. Attacking the distributors was designed to put the Eye out of business, not to redress the libels, if there were any. We said this was not a legitimate reason for suing and we persuaded a judge that we were right. He dismissed all but the three actions against Private Eye itself. Goldsmith appealed and Lord Denning, presiding over the Court of Appeal, agreed with us and gave a resounding judgment in our favour. Unfortunately, his two junior colleagues, one of whom was the future Lord Scarman, let us down badly by outvoting him. So Private Eye continued to face the whole avalanche of writs and the prospect of extinction.

Appetite for vengeance

Nor did his success in the Court of Appeal satisfy Goldsmith’s appetite for vengeance. He applied to the High Court for leave to bring a private prosecution against Ingrams and other Private Eye journalists for criminal libel. Such prosecutions were, and have remained, rare. The court must be satisfied that there is a strong public interest in a prosecution. It was also widely believed that prosecutions would only be allowed where the libel complained of threatened public order. Naturally, we challenged this move vigorously but the judge was mesmerised by Goldsmith’s commercial brilliance. He ruled that the public interest test was satisfied and that the absence of a threat to public order was immaterial. He gave leave for the prosecution to go ahead. The prospect of imprisonment now hung over the journalists.

Strange confession

Even this was not enough for Goldsmith. He believed the Eye was about to publish another damaging story—this time about his solicitor, Levine, who before setting up his own practice had been a protégé of the commercial lawyer Leslie Paisner. It was rumoured that Levine had left Paisners under a cloud. Surprisingly it was Goldsmith, not Levine himself, who decide to apply to the High Court for an injunction.

Apart from the obvious defence that Goldsmith had no standing to sue on behalf of his solicitor, we were confident of defeating this latest assault by revealing information about Levine which had been supplied by Paisner himself to a Private Eye journalist. The day before the hearing a copy of an affidavit by Paisner was delivered to my home by Levine’s messenger. It echoed the confessions made under torture by the accuseds in the Soviet show trials of the 1930s:

- “After Eric Levine left Paisner & Co., the firm of which I am senior partner, in October 1969, I have on a number of occasions seriously defamed him...I hereby unequivocally acknowledge that all these statements and allegations were lies and without any foundation whatsoever. They were part of a vicious vendetta perpetrated by me on Eric Levine...Despite my attacks against Eric Levine, he prospered. The success of his firm embittered me the more, especially when I learned that the successful Jimmy Goldsmith had become his client.”

The court was electrified when this remarkable document was read out. The judge, Mr Justice Donaldson, succinctly summarised its impact:

- “Either the man’s mad or he’s had his arm twisted.”

Unfortunately, we were unable to cross-examine Paisner. He did not appear when summoned to give evidence. Instead a doctor turned up to report that he was too ill. He died a few months later, leaving unsolved the mystery of his strange confession and the likely role of Goldsmith in extracting it.

We won that round but the civil and criminal libel trials still loomed. Then, an opportunity to resolve the whole affair occurred. Goldsmith fancied himself as a newspaper magnate and tried to buy The Observer.

The journalists on that paper were incensed by his persecution of Private Eye and objected strenuously to the prospect of becoming his employees while the litigation continued. Goldsmith realised he could not achieve his ambition without ending the dispute. A settlement was negotiated on terms very favourable to Private Eye: publication of an apology and a modest contribution to Goldsmith’s legal costs, by instalments spread over 10 years. The criminal prosecution was withdrawn at a brief hearing at the Old Bailey.

Settling the dispute was not, however, enough to clinch a deal with The Observer. The wealthy bully who tried to use the law to intimidate had overreached himself. A warning, perhaps, to others similarly tempted.[18]

References

- ↑ Bindman, Sir Geoffrey (Lionel). Who's Who 2011. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 July 2011.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "BIHR Trustees". United Kingdom: British Institute of Human Rights. Retrieved 20 July 2011.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "2007 New Years' Honours List". Cabinet Office Ceremonial Secretariat. Retrieved 20 July 2011.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Bindmans: about us". United Kingdom: Bindmans LLP. Retrieved 20 July 2011.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Petition to compensate British diplomat Patrick Haseldine"

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ "Sir James Goldsmith’s tale is a warning to those tempted to use the law to intimidate, says Geoffrey Bindman"

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here