Civil Cooperation Bureau

(Hit squad, Intelligence agency) | |

|---|---|

Civil Cooperation Bureau HQ in Pretoria | |

| Abbreviation | CCB |

| Founder | |

| Parent organization | South African Defence Force |

| Headquarters | Rietondale, Pretoria, South Africa |

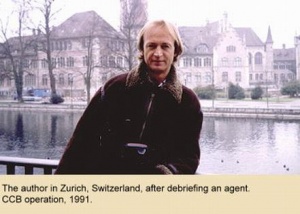

The Civil Cooperation Bureau (CCB) (Afrikaans: Burgerlike Samewerkingsburo, BSB) was a covert unit of the South African Defence Force (SADF) whose operations were under the authority of Defence Minister General Magnus Malan during the 1980s in the apartheid era. The CCB operated domestically as well as abroad, and reported directly to State President P W Botha. CCB headquarters was located in the suburb of Rietondale in the capital Pretoria, nearby to the Union Buildings and to the presidential residence of Libertas.

Perhaps the most controversial of South Africa's security apparatus, the CCB has been accused of torture, human experiments, political assassinations and the training and funding of militant groups throughout the world. The CCB was among the most secretive of the apartheid regime's agencies along with the National Intelligence Service and the SADF's nuclear development programme. Second only to the Defence Force and its activities, the CCB received the largest annual budget among all the country's departments, however the exact amount has remained classified. The CCB represented a new method of state-directed warfare in the South African context, part of the South African Special Forces but structured and functioning in a way intended to make it seem it was not.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission considered the CCB to be responsible for numerous killings, and suspected it of many more.[1]

Contents

Forerunners and contemporaries

When South African newspapers first revealed its existence in the late 1980s, the CCB appeared to be a unique and unorthodox security operation: its members wore civilian clothing; it operated within the borders of the country; it used private companies as fronts; and it mostly targeted civilians. However, as the TRC discovered a decade later, the CCB's methods were neither new nor unique. Instead, they had evolved from precedents set in the 1960s and 70s by Eschel Rhoodie’s Department of Information (see Muldergate Scandal[2]), the Bureau of State Security (BOSS) and Project Barnacle (a top-secret project to eliminate SWAPO detainees and other "dangerous" operators).[3]

From information given to the TRC by former agents seeking amnesty for crimes committed during the apartheid era, it became clear that there were many other covert operations similar to the CCB, which Nelson Mandela would label the Third Force. These operations included Wouter Basson’s 7 Medical Battalion Group,[4] the Askaris, Witdoeke, and C1/C10 or Vlakplaas.

Besides these, there were also political front organisations like the International Freedom Foundation, Marthinus van Schalkwyk's Jeugkrag (Youth for South Africa),[5] and Russel Crystal's National Student Federation[6] which would demonstrate that while the tactics of the South African government varied, the logic remained the same: Total onslaught demanded a total strategy.[7]

General Malan and the CCB

In his 1997 submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission,[8] General Malan described the CCB as follows:

- "15.1 Let me now deal with the matter of the CCB. The CCB organisation as a component of Special Forces was approved in principle by me. Special Forces was an integral and supportive part of the South African Defence Force. The role envisaged for the CCB was the infiltration and penetration of the enemy, the gathering of information and the disruption of the enemy. The CCB was approved as an organisation consisting of ten divisions, or as expressed in military jargon, regions. Eight of these divisions or regions were intended to refer to geographical areas. The area of one of these regions, Region Six, referred to the Republic of South Africa. The fact that the organisation in Region Six was activated, came to my knowledge for the first time in November 1989. The CCB provided the South African Defence Force with good covert capabilities.

- "15.2 During my term of office as Head of the South African Defence Force and as Minister of Defence instructions to members of the South African Defence Force were clear: destroy the terrorists, their bases and their capabilities. This was also government policy. As a professional soldier, I issued orders and later as Minister of Defence I authorised orders which led to the death of innocent civilians in cross-fire. I sincerely regret the civilian casualties, but unfortunately this is part of the ugly reality of war. However, I never issued an order or authorised an order for the assassination of anybody, nor was I ever approached for such authorisation by any member of the South African Defence Force. The killing of political opponents of the government, such as the slaying of Dr David Webster, never formed part of the brief of the South African Defence Force."

Recognition

Reports about the CCB were first published in 1990 by the now-defunct weekly Vrye Weekblad, and more detailed information emerged later in the 1990s at a number of TRC amnesty hearings. General Joep Joubert, in his testimony before the TRC, revealed that the CCB was a long-term Special Forces project in the South African Defence Force. It had evolved from the 'offensive defence' philosophy prevalent in P W Botha's security establishment.[9]

Nominally a civilian organisation that could be plausibly disowned by the apartheid government, the CCB drew its operatives from the SADF itself or the South African Police. According to Joubert, many operatives did not know that they were members of an entity called the CCB.[10]

In the wake of the National Party government's Harms Commission, whose proceedings were considered seriously flawed by analysts and the official opposition, the CCB was disbanded in August 1990.[11] Some members were transferred to other security organs.[12] No prosecutions resulted.

Management Board

Heading this structure was a management board chaired by the GOC Special Forces – Major General Joep Joubert (1985–89) followed by Major General Eddie Webb from the beginning of 1989. Other board members were the managing director (Verster), his deputy (Dawid Fourie), a regional co-ordinator (Wouter Basson), finance (Theuns Kruger) and administrative or production manager (Lafras Luitingh). Others named as members of the CCB’s inner core were its intelligence chief, Christoffel Nel, and ex-Special Forces operatives Commandants Charl Naudé and Corrie Meerholtz.[13]

Regional Structure

The CCB was structured along regional lines. There were ten regions in all, eight geographic and two organisational. These were Botswana (1); Mozambique and Swaziland (2); Lesotho (3); Angola, Zambia and Tanzania (4); International/Europe (5); South Africa (6); Zimbabwe (7); South-West Africa (Namibia) (8); Intelligence (9); and Finance and Administration (10).[13]

Botswana

In region 1 (Botswana) the regional manager up to 1988 was Commandant Charl Naudé and thereafter Dawid Fourie, while Christo Nel (aka Derek Louw) handled the intelligence function.[13]

Mozambique and Swaziland

In region 2 (Mozambique and Swaziland) the manager was Commandant Corrie Meerholtz (aka Kerneels Koekemoer) until the end of 1988, when he left to take charge of 5 Recce. He was replaced by the operational co-ordinator, Captain Pieter Botes.[13]

Lesotho

Fourie was also the manager in region 3 (Lesotho), while the intelligence function was performed by Peter Stanton, one of the few remaining ex-Rhodesians from the D40 and Barnacle eras.[14]

Angola, Zambia and Tanzania

Dawid Fourie was also responsible for region 4 (Angola, Zambia and Tanzania), taking it over in 1988 from Meerholtz. Christo Nel handled the intelligence function while Ian Strange (aka Rodney) was also involved in this region.[15]

International/Europe

In terms of Region 5 (European and International), Joseph Niemoller Jr appears to have been coordinator until 1987, when he was suddenly withdrawn following the arrest of a number of individuals living in England on charges of plotting to kill ANC leaders.

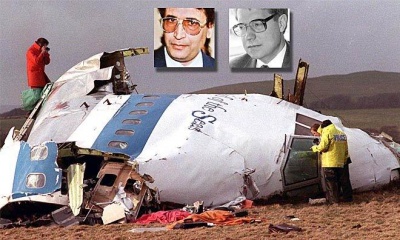

Niemoller's replacement Eeben Barlow was accused of carrying out the December 1988 Lockerbie bombing on the orders of the South African State Security Council under the direction of Craig Williamson.[16]

South Africa

Eight people applied to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for amnesty in connection with the CCB's Regions Six, which covered activities internal to South Africa itself: Major General Edward Webb, GOC Special Forces and ‘Chairman’ of the CCB; Colonel Pieter Johan ‘Joe’ Verster, ‘Managing Director’ of the CCB; Wouter Jacobus Basson, aka Christo Brits, co-ordinator of Region Six; Daniel du Toit ‘Staal’ Burger, manager of Region Six; Leon Andre ‘Chappies’ Maree, Region Six, responsible for Natal; Carl Casteling ‘Calla’ Botha, Region Six, responsible for Transvaal ; Abram ‘Slang’ van Zyl, Region Six, responsible for the Western Cape, and Ferdinand ‘ Ferdi’ Barnard.[17]

Zimbabwe

Various CCB members co-ordinated region 7 (Zimbabwe) including Wouter Basson and Lafras Luitingh. Others involved in sub-management were Ferdi Barnard (for a brief period) and Alan Trowsdale.[15]

South-West Africa

Region 8 (South-West Africa) was headed by Roelf van Heerden (aka Roelf van der Westhuizen).[15]

Operations

Although there is no published record covering all operations conducted during the CCB's five-year existence, it is estimated that 85-100 active operations were conducted, including:

- Bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 of 21 December 1988 by CCB Region 5 chief Eeben Barlow[18] In a 2011 article entitled "Lockerbie: Ayatollah's Vengeance Exacted by Botha's Regime", former diplomat Patrick Haseldine alleged that operatives of the apartheid regime's Civil Cooperation Bureau cut the padlock on security door CP2 at Heathrow airport, leading to the Pan Am baggage area, and planted the suitcase bomb which sabotaged Clipper Maid of the Seas over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988.[19]

- Bombing of a Western Cape kindergarten - the Early Learning Centre - on the evening of 31 August 1989[20]

- Harassment of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, by hanging a baboon foetus in the garden of his Cape Town home in 1989 in the hope that it would bewitch him[21]

- Killing of

- Tsitsi Chiliza, the wife of an ANC member killed in an operation targeted at Jacob Zuma - 11 May 1987

- Christopher, by injection on the way to Zeerust, North West in a vehicle in which operatives Danie Phaal and Trevor Floyd were traveling[22]

- South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) activist Anton Lubowski on 12 September 1989[23]

- Jacob 'Boy' Molekwane

- ANC activist, Gibson Ncube (also known by the surname Mondlane) by poisoning

- Matsela Polokela[24] - some TRC documents misspell the surname 'Pokolela'[25]

- Dulcie September in Paris - 29 March 1988. Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage (French Secret Service) involvement is alleged.[26]

- Dr David Webster - Wits University academic and anti-apartheid activist killed by Ferdi Barnard 1 May 1989, outside the Eleanor Street, Troyeville, Johannesburg home he shared with partner Maggie Friedman[27]

- Supplying materials to SAP members for the 1986 killing of KwaNdebele cabinet minister Piet Ntuli[28]

- Alleged harassment of

- Afrikaner dissident and Vrye Weekblad editor Max du Preez by pointing an RPG7 at him while forcing him to consume a large amount of mampoer or moonshine[29]

- Actor and playwright Hannes Muller for his role in Somewhere on the Border, a play banned by the authorities for its criticism of the South African Border War[30]

- Alleged shooting of Danger Nyoni - 12 December 1986

- Attempted contamination of drinking water in a Namibian refugee camp, by introducing cholera bacterium into it, in an effort to disrupt that country's independence from South Africa[31][32]

- Attempted assault on UN Special Representative, Martti Ahtisaari, in Namibia - 1989. According to a hearing in September 2000 of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, two CCB operatives (Kobus le Roux and Ferdinand Barnard) were tasked not to kill Ahtisaari, but to give him "a good hiding". To carry out the assault, Barnard had planned to use the grip handle of a metal saw as a knuckleduster. In the event, Ahtisaari did not attend the meeting at the Keetmanshoop Hotel, where Le Roux and Barnard lay in wait for him, and thus escaped injury.[33]

- Attempted killing of

- Jeremy Brickhill in Harare - 13 October 1987[34]

- Reverend Frank Chikane by poisoning - 1989

- Father Michael Lapsley,[35] who lost both hands and an eye in a letter bomb attack in Harare - 28 April 1990

- Godfrey Motsepe in Brussels - 4 February 1988

- January Masilela — known as "Che O'Gara", his Umkhonto we Sizwe nom-de-guerre.[36] On 30 September 2002, Masilela wrote to the South African Special Forces League conferring the Defence Minister's recognition of the SFL as being "legally representative of the interests of military veterans."

- Dullah Omar[37] - 1989

- Anton Roskam - incorrectly spelled Rosskam in TRC transcripts, received threatening letters, car was set alight[38]

- Albie Sachs - by bombing in Maputo in which he lost an arm and sight in one eye while in a car borrowed from Indres Naidoo thought to have been the CCB's intended target.[39]

Not carried out

According to TRC records,[40][41][42] CCB operatives were tasked to seriously injure Martti Ahtisaari, UN Special Representative in Namibia,[43] and to eliminate the following but did not succeed in carrying out their tasks:

- South African journalist Gavin Evans

- Theo-Ben Gurirab

- Hidipo Hamutenya

- Pallo Jordan and Ronnie Kasrils[44]

- Gwen Lister

- Winnie Mandela

- Kwenza Mhlaba

- Jay Naidoo

- Joe Slovo

- Stompie Sepei

- Oliver Tambo

- Daniel Tjongarero

- Andimba Toivo ya Toivo

- Roland White

References

- ↑ "Civil Cooperation Bureau of South Africa"

- ↑ Sanders, J "Apartheid’s friends", pages=34–55, (2006) John Murray (London)

- ↑ "Confession 'built case against Basson'"

- ↑ "The South African Chemical and Biological Warfare Programme"

- ↑ "Marthinus `moet om amnestie vra, soos ANC-spioene"

- ↑ "The Making of a Lobbyist"

- ↑ "The life and times of P W Botha"

- ↑ "Submission to The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Gen M A de Malan"

- ↑ "The Transformation of Military Intelligence and Special Forces. Towards an Accountable and Transparent Military Culture."

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, pp. 137-8.

- ↑ "Human Rights Watch. (1991). The Killings in South Africa: The Role of the Security Forces and the Response of the State." ISBN 0-929692-76-4 Accessed 16 May 2007

- ↑ "Transcript of proceedings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (Day 18)" 29 September 2000. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ↑ a b c d Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report - Volume Two, Chapter Two, p139.

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report - Volume Two, Chapter Two, pp139-140.

- ↑ a b c Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report - Volume Two, Chapter Two, p140.

- ↑ "Major Craig Williamson: the 'real' Lockerbie bomber"

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume Six, Section Three, Chapter One, p246, accessed 13 April 2008.

- ↑ "Lockerbie: J'accuse....Eeben Barlow"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Ayatollah's Vengeance Exacted by Botha's Regime"

- ↑ "I won't apologise, says CCB boss"

- ↑ "Baboon foetus 'sent to bewitch Tutu'" Independent Newspapers Youthvote.

- ↑ Author unknown. (1998). A self-confessed apartheid era assassin told the Pretoria High Court yesterday that he did not apply for amnesty for his deeds, with one exception, because he believed his seniors, who gave him the orders, were the ones who should be punished. Business Day.

- ↑ Author unknown. (1998). TRC clears Lubowski's name. The Namibian. Accessed 3 December 2007.

- ↑ African National Congress, List of ANC Members who Died in Exile. March 1960 - December 1993. Accessed 21 May 2007

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, p. 110. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ↑ "Demilitarisation and Peace-building in Southern Africa" ISBN 0-7546-3315-2

- ↑ Author unknown. (1998). Former Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) agent Ferdi Barnard has admitted for the first time to murdering activist and academic David Webster in 1989 on instructions of then CCB head, Joe Verster. Business Day.

- ↑ SAPA. (1999). Joubert authorises car bomb that killed Piet Ntuli.

- ↑ Author unknown (2005). Die geskiedenis van Vrye Weekblad in 170 bladsye. Die Burger. Accessed 12 December 2007

- ↑ Author unknown. (2007). Van bliksem tot grotman. Die Burger. Accessed 12 December 2007

- ↑ Associated Press. (1990). Paper Says Pretoria Put Germs in Namibian Water. New York Times, 12 May. Accessed 17 May 2007..

- ↑ Burgess, S. & Purkitt, H. (undated). The secret program. South Africa’s chemical and biological weapons. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ↑ "Targeted by the Civil Cooperation Bureau"

- ↑ von Paleske, A. (undated). Woods was part of murky past. The Zimbabwean. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ↑ South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Video Collection. Yale Law School Lilian Goldman Library. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ↑ Structures and personnel of the ANC and MK

- ↑ Author unknown. (1998). The top structure of the defence force's Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) had given the go-ahead in 1989 for the elimination of Dullah Omar and offered a well-known Cape Flats gangster R15 000 to gun down the future justice minister, the high court heard yesterday. Business Day. Accessed 16 May 2007.

- ↑ "OMAR WAS LUCKY BARNARD DIDN'T KILL HIM: PTA HIGH COURT TOLD"

- ↑ "Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s." Galago (2001)

- ↑ "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report", Volume 2, p. 141. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ↑ Walker, A. (2000). How an assassin bungled a deadly umbrella plot The Independent, 13 May.

- ↑ SAPA. (1998). Winnie and Tutu were on Ferdi Barnard's hit list: ex-wife

- ↑ Transcript of proceedings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (Day 17), 28 September 2000. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ↑ Author unknown. (2000). A self-confessed apartheid era assassin told the Pretoria High Court yesterday that he did not apply for amnesty for his deeds, with one exception, because he believed his seniors, who gave him the orders, were the ones who should be punished. Business Day. Accessed 17 May 2007.