Difference between revisions of "Operation Gladio/Exposure"

(Redirected page to Operation Gladio#Exposure) |

(Import) Tag: Removed redirect |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{event | |

| + | |wikipedia= | ||

| + | |start= | ||

| + | |end= | ||

| + | |locations=Italy | ||

| + | |URL= | ||

| + | |constitutes=Exposure | ||

| + | |description=Operation Gladio was exposed in Italy by the research of Italian judge Felice Casson. | ||

| + | }}'''Operation Gladio has been exposed''' since operational details are now publicly available, and official bodies such as national governments and [[NATO]] have admitted that the operation existed. However, although some low level operatives have been imprisoned, key parts of it remain hidden. The [[Operation Gladio/B]] claims made by [[Sibel Edmonds]] are not part of the official record - the US authorities chose to subject her to legal gagging order. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Earlier discoveries== | ||

| + | In [[1978]], [[Norwegian Police]] tracking a small scale illegal moonshine operation stumbled on a cache of arms in a secret basement under the house of shipowner/spook [[Hans Otto Meyer]]. [[Norway's Minister of Defence]], [[Rolf Hansen]] told the [[Norwegian parliament]] admitted that privately organized resistance groups were controlled by the intelligence agencies, but denied that they were answerable to NATO and dismissed any connections to the CIA.<ref>https://apnews.com/a37c019c2b35ad226891e339a9b94d48</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Felice Casson== | ||

| + | In 1984 an Italian [[judge]] [[Felice Casson]] reopened the case of a [[car bomb in Peteano]] in 1972 and uncovered a series of anomalies in the original investigation. [[General Mingarelli]], head of the head of the caribinieri in the Udine region, was later found guilty of diverting this investigation and sentenced to 10 years (later reduced to 2½ years).<ref>[[Operation Gladio (film)]]</ref> | ||

| + | [[image:Peteano bombing.png|left|278px|thumbnail|The remains of the Fiat 500 after the 1972 [[Peteano bombing]]]] | ||

| + | Following the discovery of an arms cache near Trieste in 1972 containing [[C4 explosive]]s identical to that used in the Peteano attack, Casson's investigation revealed that although originally blamed on the communist [[Red Brigades]], the bombing in Peteano was the work of the military secret service [[Servizio Informazioni Difesa]] in conjunction with [[Ordine Nuovo]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Judge Casson’s investigation also revealed that the 1972 [[Peteano bombing]] was the continuation of a series of bombings begun at Christmas 1969, the most well-known of which, on the [[Piazza Fontane]] in [[Milan]], killed 16 and injured 80. The bombing campaign culminated on 2 August 1980 with a massive [[Bologna massacre|bomb in the waiting room of Bologna railway station]] which killed 85 and injured 200. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The Strategy of Tension== | ||

| + | {{FA|Strategy of Tension}} | ||

| + | During his trial, [[Vincenzo Vinciguerra]] revealed that, in addition to discrediting left wing political groups, there had been a second aim behind the bombings - to inculcate a climate of [[fear]] among the general populace. This was known as the '[[strategy of tension]]' which was intended to generate a pervasive sense of fear which would encourage the population to appeal to the state for protection. As Vincenzo Vinciguerra summarized during his trial: | ||

| + | {{QB | ||

| + | |‘You had to attack civilians, the people, women, children, innocent people, unknown people far removed from any political game. The reason was quite simple. They were supposed to force these people, the Italian public to turn to the State to ask for greater security.’ | ||

| + | Daniele Ganser - [http://web.archive.org/web/20051130003012/http://www.isn.ethz.ch/php/documents/collection_gladio/synopsis.htm NATO's Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | In [[Operation Gladio (film)|Francovich's documentary on Gladio]], he described the aim as to ‘destabilise in order to stabilise’… ‘To create tension within the country to promote conservative, reactionary social and political tendencies.’ | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==SISMI Archives== | ||

| + | [[image:Bologna1.jpg|right|333px]] | ||

| + | In 1990 Judge Casson was given permission by [[Italy/Prime minister|Prime minister]] [[Giulio Andreotti]] to search the archives of the Italian military secret service [[Servizio informazioni sicurezza Militare]]) where he found proof of the existence of the Gladio network, and links to NATO and the United States. Following this, on 3 August 1990 prime minister Andreotti confirmed to parliament the existence of the Gladio networks but claimed they had ceased operating in 1972. This was subsequently revealed to be false by the Italian press. Andreotti then admitted the existence of the Gladio networks and their connection to NATO. | ||

| + | {{QB | ||

| + | |The secret Gladio army, as Andreotti revealed, was well armed. The equipment provided by the CIA was buried in 139 hiding spots across the country in forests, meadows and even under churches and cemeteries. According to the explanations of Andreotti the Gladio caches included 'portable arms, ammunition, explosives, hand grenades, knives and daggers, 60 mm mortars, several 57 mm recoilless rifles, sniper rifles, radio transmitters, binoculars and various tools'. Andreotti's sensational testimony did not only lead to an outcry concerning the corruption of the government and the CIA among the press and the population, but also to a hunt for the secret arms caches. Padre Giuciano recalls the day when the press came to search for the hidden Gladio secrets in his church with ambiguous feelings: 'I was forewarned in the afternoon when two journalists from "Il Gazzettino" asked me if I knew anything about arms deposits here at the church. They started to dig right here and found two boxes right away. Then the text also said a thirty centimetres from the window. So they came over here and dug down. One box was kept aside by them because it contained a phosphorous bomb. They sent the Carabinieri outside whilst two experts opened this box, another had two machine guns in it. All the guns were new, in perfect shape. They had never been used.'<br/> | ||

| + | (DG p. 12) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | But he denied the claim of Vinceguerra that the Gladio armies had been involved in the domestic terrorism the country had witnessed. Despite that, a parliamentary commission in 2000 investigating Gladio explicitly rejected his denial and concluded to the contrary: | ||

| + | {{QB | ||

| + | |‘Those massacres, those bombs, those military actions had been organised or promoted or supported by men inside Italian state institutions and, as has been discovered more recently, by men linked to the structures of United States intelligence.’ <br/> | ||

| + | (DG p.14) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

| + | {{Stub}} | ||

Revision as of 07:22, 8 January 2020

| Location | Italy |

|---|---|

| Description | Operation Gladio was exposed in Italy by the research of Italian judge Felice Casson. |

Operation Gladio has been exposed since operational details are now publicly available, and official bodies such as national governments and NATO have admitted that the operation existed. However, although some low level operatives have been imprisoned, key parts of it remain hidden. The Operation Gladio/B claims made by Sibel Edmonds are not part of the official record - the US authorities chose to subject her to legal gagging order.

Contents

Earlier discoveries

In 1978, Norwegian Police tracking a small scale illegal moonshine operation stumbled on a cache of arms in a secret basement under the house of shipowner/spook Hans Otto Meyer. Norway's Minister of Defence, Rolf Hansen told the Norwegian parliament admitted that privately organized resistance groups were controlled by the intelligence agencies, but denied that they were answerable to NATO and dismissed any connections to the CIA.[1]

Felice Casson

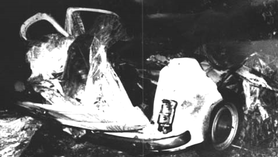

In 1984 an Italian judge Felice Casson reopened the case of a car bomb in Peteano in 1972 and uncovered a series of anomalies in the original investigation. General Mingarelli, head of the head of the caribinieri in the Udine region, was later found guilty of diverting this investigation and sentenced to 10 years (later reduced to 2½ years).[2]

Following the discovery of an arms cache near Trieste in 1972 containing C4 explosives identical to that used in the Peteano attack, Casson's investigation revealed that although originally blamed on the communist Red Brigades, the bombing in Peteano was the work of the military secret service Servizio Informazioni Difesa in conjunction with Ordine Nuovo.

Judge Casson’s investigation also revealed that the 1972 Peteano bombing was the continuation of a series of bombings begun at Christmas 1969, the most well-known of which, on the Piazza Fontane in Milan, killed 16 and injured 80. The bombing campaign culminated on 2 August 1980 with a massive bomb in the waiting room of Bologna railway station which killed 85 and injured 200.

The Strategy of Tension

- Full article: Strategy of Tension

- Full article: Strategy of Tension

During his trial, Vincenzo Vinciguerra revealed that, in addition to discrediting left wing political groups, there had been a second aim behind the bombings - to inculcate a climate of fear among the general populace. This was known as the 'strategy of tension' which was intended to generate a pervasive sense of fear which would encourage the population to appeal to the state for protection. As Vincenzo Vinciguerra summarized during his trial:

‘You had to attack civilians, the people, women, children, innocent people, unknown people far removed from any political game. The reason was quite simple. They were supposed to force these people, the Italian public to turn to the State to ask for greater security.’

Daniele Ganser - NATO's Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe

In Francovich's documentary on Gladio, he described the aim as to ‘destabilise in order to stabilise’… ‘To create tension within the country to promote conservative, reactionary social and political tendencies.’

SISMI Archives

In 1990 Judge Casson was given permission by Prime minister Giulio Andreotti to search the archives of the Italian military secret service Servizio informazioni sicurezza Militare) where he found proof of the existence of the Gladio network, and links to NATO and the United States. Following this, on 3 August 1990 prime minister Andreotti confirmed to parliament the existence of the Gladio networks but claimed they had ceased operating in 1972. This was subsequently revealed to be false by the Italian press. Andreotti then admitted the existence of the Gladio networks and their connection to NATO.

The secret Gladio army, as Andreotti revealed, was well armed. The equipment provided by the CIA was buried in 139 hiding spots across the country in forests, meadows and even under churches and cemeteries. According to the explanations of Andreotti the Gladio caches included 'portable arms, ammunition, explosives, hand grenades, knives and daggers, 60 mm mortars, several 57 mm recoilless rifles, sniper rifles, radio transmitters, binoculars and various tools'. Andreotti's sensational testimony did not only lead to an outcry concerning the corruption of the government and the CIA among the press and the population, but also to a hunt for the secret arms caches. Padre Giuciano recalls the day when the press came to search for the hidden Gladio secrets in his church with ambiguous feelings: 'I was forewarned in the afternoon when two journalists from "Il Gazzettino" asked me if I knew anything about arms deposits here at the church. They started to dig right here and found two boxes right away. Then the text also said a thirty centimetres from the window. So they came over here and dug down. One box was kept aside by them because it contained a phosphorous bomb. They sent the Carabinieri outside whilst two experts opened this box, another had two machine guns in it. All the guns were new, in perfect shape. They had never been used.'

(DG p. 12)

But he denied the claim of Vinceguerra that the Gladio armies had been involved in the domestic terrorism the country had witnessed. Despite that, a parliamentary commission in 2000 investigating Gladio explicitly rejected his denial and concluded to the contrary:

‘Those massacres, those bombs, those military actions had been organised or promoted or supported by men inside Italian state institutions and, as has been discovered more recently, by men linked to the structures of United States intelligence.’

(DG p.14)