Difference between revisions of "Robin Day"

m (Text replacement - "1960s " to "1960s ") |

m (Text replacement - "Early life and education" to "Background") |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|image=Blair_and_Day.jpg | |image=Blair_and_Day.jpg | ||

|image_width=400px | |image_width=400px | ||

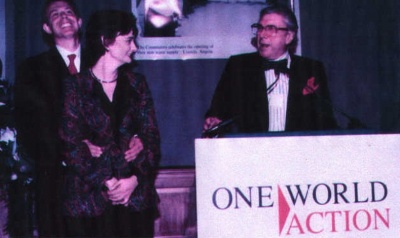

| − | |image_caption=A fringe event for [[One World Action]] at Labour's 1997 conference, chaired by Sir Robin Day and addressed by [[ | + | |image_caption=A fringe event for [[One World Action]] at Labour's 1997 conference, chaired by Sir Robin Day and addressed by Cherie and [[Tony Blair]] |

| − | |||

|birth_date=24 October 1923 | |birth_date=24 October 1923 | ||

|death_date=6 August 2000 | |death_date=6 August 2000 | ||

| Line 9: | Line 8: | ||

|wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robin_Day | |wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robin_Day | ||

|spouses=Katherine Ainslie | |spouses=Katherine Ainslie | ||

| − | |alma_mater=St Edmund Hall | + | |description="The most outstanding [UK] television journalist of his generation." |

| + | |alma_mater=St Edmund Hall (Oxford) | ||

|birth_place=London, England | |birth_place=London, England | ||

|death_place=London, England | |death_place=London, England | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

'''Sir Robin Day''''s [[obituary]] in ''[[The Guardian]]'' stated that "he was the most outstanding television journalist of his generation. He transformed the television interview, changed the relationship between [[politician]]s and television, and strove to assert balance and rationality into the medium's treatment of current affairs".<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2000/aug/08/guardianobituaries1 "Obituary by Dick Taverne"]</ref> | '''Sir Robin Day''''s [[obituary]] in ''[[The Guardian]]'' stated that "he was the most outstanding television journalist of his generation. He transformed the television interview, changed the relationship between [[politician]]s and television, and strove to assert balance and rationality into the medium's treatment of current affairs".<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2000/aug/08/guardianobituaries1 "Obituary by Dick Taverne"]</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Background== | |

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

Robin Day was the son of a telephone engineer who became telephone manager at Gloucester. He attended Brentwood School from 1934 to 1938,<ref>[http://www.brentwoodschool.co.uk/famous-obs.html "List of Old Brentwoods"]</ref> briefly attended The Crypt School, Gloucester, and later Bembridge School on the Isle of Wight. | Robin Day was the son of a telephone engineer who became telephone manager at Gloucester. He attended Brentwood School from 1934 to 1938,<ref>[http://www.brentwoodschool.co.uk/famous-obs.html "List of Old Brentwoods"]</ref> briefly attended The Crypt School, Gloucester, and later Bembridge School on the Isle of Wight. | ||

| − | == | + | == Background == |

| − | Robin Day | + | Robin Day reached the rank of Captain in the UK the army in [[East Africa]], but was demoted to Lieutenant as part of a cull of rear-echelon jobs. After [[WW2]] Robin Day attended [[St Edmund Hall, Oxford]], and, while a student, was elected president of the Oxford Union debating society. Day also took part in a debating tour of the United States, run by the English-Speaking Union. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | After | ||

| − | + | == Career == | |

| + | Day was called to the Bar in 1952, but practised only briefly. In his memoirs he recorded that he secured the acquittal of a lorry-driver accused of indecent exposure by persuading the magistrates that the man had been "shaking the drops from his person" after urinating, and by getting the man's young wife to testify, wearing a tight sweater, that she and her husband enjoyed a healthy love life. | ||

==Politics== | ==Politics== | ||

| − | In the 1959 General Election Robin Day stood as a Liberal Party candidate for Hereford but failed to win. | + | In the [[1959 UK General Election]] Robin Day stood as a Liberal Party candidate for Hereford but failed to win. |

==Media== | ==Media== | ||

| − | Robin Day spent almost his entire working life in journalism. He rose to prominence on the new Independent Television News (ITN) from 1955, when he was the first British journalist to interview Egypt's President Nasser after the Suez Crisis. | + | Robin Day spent almost his entire working life in journalism. He rose to prominence on the new Independent Television News (ITN) from 1955, when he was the first British journalist to interview Egypt's President Nasser after the [[Suez Crisis]]. |

On television, he presented ''Panorama'' and chaired the [[BBC]]'s ''Question Time'' (1979–89), and on radio was presenter of ''The World at One'' from 1979 to 1987. His incisive and sometimes – by the standards of the day – abrasive interviewing style, together with his heavy-rimmed spectacles and trademark bow tie, made him an instantly recognisable and frequently impersonated figure over five decades. | On television, he presented ''Panorama'' and chaired the [[BBC]]'s ''Question Time'' (1979–89), and on radio was presenter of ''The World at One'' from 1979 to 1987. His incisive and sometimes – by the standards of the day – abrasive interviewing style, together with his heavy-rimmed spectacles and trademark bow tie, made him an instantly recognisable and frequently impersonated figure over five decades. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 37: | ||

He became known in British broadcasting as 'the Grand Inquisitor' for his abrasive interviewing of politicians, a style out of keeping with the British media's culture of deference to authority that prevailed during the early days of his career. | He became known in British broadcasting as 'the Grand Inquisitor' for his abrasive interviewing of politicians, a style out of keeping with the British media's culture of deference to authority that prevailed during the early days of his career. | ||

| − | In 1958 he interviewed Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, in what the ''Daily Express'' called: "the most vigorous cross-examination a prime minister has been subjected to in public". The interview turned Macmillan into a television personality, and was probably the first time that British television became a serious part of the political process. | + | In 1958 he interviewed [[UK Prime Minister]] [[Harold Macmillan]], in what the ''Daily Express'' called: "the most vigorous cross-examination a prime minister has been subjected to in public". The interview turned Macmillan into a television personality, and was probably the first time that British television became a serious part of the political process. |

| − | In the early 1970s, Robin Day was involved on BBC Radio, where he proved an innovator with ''It's Your Line'' (1970–76). This was a national phone-in programme that enabled ordinary people, for the first time, to put questions directly to the prime minister and other politicians (it later spawned ''Election Call''). He also presented ''The World At One'', from 1979 to 1987. In 1981, he was knighted for his services to broadcasting. | + | In the early 1970s, Robin Day was involved on [[BBC Radio]], where he proved an innovator with ''It's Your Line'' (1970–76). This was a national phone-in programme that enabled ordinary people, for the first time, to put questions directly to the prime minister and other politicians (it later spawned ''Election Call''). He also presented ''The World At One'', from 1979 to 1987. In 1981, he was knighted for his services to broadcasting. |

| − | In October 1982, during an interview with the | + | In October 1982, during an interview with the [[Secretary of State for Defence]] [[John Nott]], pursuing cuts in defence expenditure, he posed the question: "But why should the public, on this issue, as regards the future of the [[Royal Navy]], believe you, a transient, here-today and, if I may say so, gone-tomorrow politician, [a reference to Nott's announcement that he was to stand down at the next General Election] rather than a senior officer of many years?" Nott rose, removed his microphone, and said "I'm sorry, I'm fed up with this interview. Really, it's ridiculous" and walked off the set. Nott's autobiography in 2003 was called ''Here Today Gone Tomorrow: Recollections of an Errant Politician''. |

Robin Day was a regular fixture on all BBC Election Night programmes from the [[1960s]] until 1987. After leaving ''Question Time'', he moved to the new [[British Satellite Broadcasting]] (BSB) service where he presented the weekly political discussion programme ''Now Sir Robin''. When BSB merged with [[Sky Television]] in November 1990, the programme continued to be broadcast on Sky News for a while.<ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Satellite_Broadcasting "British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB)"]</ref> On the night of the 1992 General Election, Sir Robin Day resumed his role as interviewer, this time on ITN's Election Night coverage, broadcast on ITV. | Robin Day was a regular fixture on all BBC Election Night programmes from the [[1960s]] until 1987. After leaving ''Question Time'', he moved to the new [[British Satellite Broadcasting]] (BSB) service where he presented the weekly political discussion programme ''Now Sir Robin''. When BSB merged with [[Sky Television]] in November 1990, the programme continued to be broadcast on Sky News for a while.<ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Satellite_Broadcasting "British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB)"]</ref> On the night of the 1992 General Election, Sir Robin Day resumed his role as interviewer, this time on ITN's Election Night coverage, broadcast on ITV. | ||

| Line 52: | Line 48: | ||

===The Apartheid Question=== | ===The Apartheid Question=== | ||

| − | On February 25, 1988 British diplomat [[Patrick Haseldine]] was a member of the invited studio audience of [[BBC]]'s ''[[Question Time]]'' which began transmission at 22:00. Fifteen minutes into the programme a student raised a question about that day's outlawing of 17 anti-apartheid organisations, and asked whether the British government was justified in its opposition of economic sanctions against [[South Africa]] in the face of calls for sanctions by [[Nelson Mandela]], [[Desmond Tutu|Bishop Tutu]] and by most of the European Community. The ''Question Time'' panel (Shirley Goodwin of the Health Visitors Association, Sir Russell Johnston - Liberal party spokesman on foreign affairs, Michael Meacher MP - Labour's shadow employment secretary and Michael Portillo MP junior minister at the DHSS) discussed the matter for nine minutes before the host Sir Robin Day asked if anyone in the audience had anything to add. | + | On February 25, 1988 British diplomat [[Patrick Haseldine]] was a member of the invited studio audience of [[BBC]]'s ''[[Question Time]]'' which began transmission at 22:00. Fifteen minutes into the programme a student raised a question about that day's outlawing of 17 anti-apartheid organisations, and asked whether the British government was justified in its opposition of economic sanctions against [[South Africa]] in the face of calls for sanctions by [[Nelson Mandela]], [[Desmond Tutu|Bishop Tutu]] and by most of the European Community. The ''Question Time'' panel (Shirley Goodwin of the Health Visitors Association, Sir Russell Johnston - Liberal party spokesman on foreign affairs, [[Michael Meacher]] MP - Labour's shadow employment secretary and [[Michael Portillo]] MP junior minister at the DHSS) discussed the matter for nine minutes before the host [[Sir Robin Day]] asked if anyone in the audience had anything to add. |

[[File:Patrick_Haseldine_BBCQT.jpg|300px|thumb|right|[[Patrick Haseldine]] speaking with Sir Robin Day on ''Question Time'']] | [[File:Patrick_Haseldine_BBCQT.jpg|300px|thumb|right|[[Patrick Haseldine]] speaking with Sir Robin Day on ''Question Time'']] | ||

[[File:Guardian_1.jpg|right|thumb|300px|[[Patrick Haseldine]]'s letter was published 14 days before the [[Pan Am Flight 103|Lockerbie bombing]] ]] | [[File:Guardian_1.jpg|right|thumb|300px|[[Patrick Haseldine]]'s letter was published 14 days before the [[Pan Am Flight 103|Lockerbie bombing]] ]] | ||

| Line 63: | Line 59: | ||

After his return to the [[FCO]], [[Patrick Haseldine]] wrote a letter to ''The Guardian'' on December 7, 1988 criticising PM [[Margaret Thatcher]]'s policy towards [[South Africa]]. Upon publication of the letter, the [[FCO]] again suspended Haseldine, sent him a letter of complaint in accordance with diplomatic service regulation (DSR) number 20 and scheduled an internal [[FCO]] disciplinary hearing to take place on February 28, 1989. In advance of this hearing, Haseldine wrote on January 23, 1989 to Sir Robin Day asking for a video recording of the programme in which he had appeared. The editor of ''Question Time'', [[Barbara Maxwell]], sent him Sir Robin's own VHS copy together with a covering letter sympathising with his predicament. | After his return to the [[FCO]], [[Patrick Haseldine]] wrote a letter to ''The Guardian'' on December 7, 1988 criticising PM [[Margaret Thatcher]]'s policy towards [[South Africa]]. Upon publication of the letter, the [[FCO]] again suspended Haseldine, sent him a letter of complaint in accordance with diplomatic service regulation (DSR) number 20 and scheduled an internal [[FCO]] disciplinary hearing to take place on February 28, 1989. In advance of this hearing, Haseldine wrote on January 23, 1989 to Sir Robin Day asking for a video recording of the programme in which he had appeared. The editor of ''Question Time'', [[Barbara Maxwell]], sent him Sir Robin's own VHS copy together with a covering letter sympathising with his predicament. | ||

| − | Haseldine attended the [[FCO]] hearing with his solicitor, Pamela Walsh, and brought along the video – extracts of which were screened there. The disciplinary board's questioning was largely focused on the ''Guardian'' letter and Haseldine was repeatedly asked to divulge the source of the information in the letter. However, because he had been led to believe he was under an Official Secrets Act | + | Haseldine attended the [[FCO]] hearing with his solicitor, Pamela Walsh, and brought along the video – extracts of which were screened there. The disciplinary board's questioning was largely focused on the ''Guardian'' letter and Haseldine was repeatedly asked to divulge the source of the information in the letter. However, because he had been led to believe he was under an [[Official Secrets Act 1911]] criminal investigation, he refused to be drawn on the matter lest he incriminate himself in advance of the trial. |

The disclipinary board reported on March 7, 1989 to the Permanent Under-Secretary (PUS) at the [[FCO]]. In the unpublished report, the board said its task was defined solely by DSR 20 and the letter of complaint, which excluded consideration of the ''Question Time'' issue, and it agreed unanimously that the only appropriate penalty in Haseldine's case was enforced resignation or dismissal. On March 21, 1989 the PUS wrote to Haseldine saying he should resign by – or be dismissed on – April 4, 1989 when payment of his salary would cease. | The disclipinary board reported on March 7, 1989 to the Permanent Under-Secretary (PUS) at the [[FCO]]. In the unpublished report, the board said its task was defined solely by DSR 20 and the letter of complaint, which excluded consideration of the ''Question Time'' issue, and it agreed unanimously that the only appropriate penalty in Haseldine's case was enforced resignation or dismissal. On March 21, 1989 the PUS wrote to Haseldine saying he should resign by – or be dismissed on – April 4, 1989 when payment of his salary would cease. | ||

| − | Haseldine appealed against this decision in a letter dated March 22, 1989 to the foreign secretary, Sir Geoffrey Howe. At the start of the summer parliamentary recess on July 19, 1989 Sir Geoffrey Howe's private secretary, Stephen Wall, wrote informing Haseldine that his appeal had been rejected and that he should submit his resignation by August 2, 1989 or be dismissed on that date. He did not resign and the private secretary wrote again on August 4, 1989 (four days after Sir Geoffrey Howe had been demoted and replaced as foreign secretary by [[John Major]]) confirming that Haseldine had in fact been dismissed from the Diplomatic Service on August 2, 1989.<ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2806455434754&l=400a8947c4 "Letter to ''The Guardian'' 7 December 1988"]</ref> | + | Haseldine appealed against this decision in a letter dated March 22, 1989 to the foreign secretary, Sir [[Geoffrey Howe]]. At the start of the summer parliamentary recess on July 19, 1989 Sir Geoffrey Howe's private secretary, Stephen Wall, wrote informing Haseldine that his appeal had been rejected and that he should submit his resignation by August 2, 1989 or be dismissed on that date. He did not resign and the private secretary wrote again on August 4, 1989 (four days after Sir [[Geoffrey Howe]] had been demoted and replaced as foreign secretary by [[John Major]]) confirming that Haseldine had in fact been dismissed from the Diplomatic Service on August 2, 1989.<ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2806455434754&l=400a8947c4 "Letter to ''The Guardian'' 7 December 1988"]</ref> |

==Televising Parliament== | ==Televising Parliament== | ||

| Line 78: | Line 74: | ||

==Personal life== | ==Personal life== | ||

| − | In 1965, Robin Day married Katherine Ainslie, an Australian law don at St Anne's College, Oxford, and they had two sons. The marriage was dissolved in 1986. One of the tragedies of his life was that his elder son never fully recovered from the effects of multiple skull fractures he sustained in a childhood fall. | + | In 1965, Robin Day married Katherine Ainslie, an Australian law don at [[St Anne's College, Oxford]], and they had two sons. The marriage was dissolved in 1986. One of the tragedies of his life was that his elder son never fully recovered from the effects of multiple skull fractures he sustained in a childhood fall. |

In the 1980s, Day had a coronary bypass, and he suffered from breathing problems that were often evident when he was on the air. He had always fought against a tendency to put on weight. As an undergraduate, he weighed 108 kilos and claimed that, in the course of his life, he had succeeded in losing more weight than any other person. | In the 1980s, Day had a coronary bypass, and he suffered from breathing problems that were often evident when he was on the air. He had always fought against a tendency to put on weight. As an undergraduate, he weighed 108 kilos and claimed that, in the course of his life, he had succeeded in losing more weight than any other person. | ||

Latest revision as of 12:41, 13 September 2024

(soldier, broadcaster) | |

|---|---|

A fringe event for One World Action at Labour's 1997 conference, chaired by Sir Robin Day and addressed by Cherie and Tony Blair | |

| Born | 24 October 1923 London, England |

| Died | 6 August 2000 (Age 76) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | St Edmund Hall (Oxford) |

| Children | 2 |

| Spouse | Katherine Ainslie |

| Member of | The Other Club |

"The most outstanding [UK] television journalist of his generation." | |

Sir Robin Day's obituary in The Guardian stated that "he was the most outstanding television journalist of his generation. He transformed the television interview, changed the relationship between politicians and television, and strove to assert balance and rationality into the medium's treatment of current affairs".[1]

Contents

Background

Robin Day was the son of a telephone engineer who became telephone manager at Gloucester. He attended Brentwood School from 1934 to 1938,[2] briefly attended The Crypt School, Gloucester, and later Bembridge School on the Isle of Wight.

Background

Robin Day reached the rank of Captain in the UK the army in East Africa, but was demoted to Lieutenant as part of a cull of rear-echelon jobs. After WW2 Robin Day attended St Edmund Hall, Oxford, and, while a student, was elected president of the Oxford Union debating society. Day also took part in a debating tour of the United States, run by the English-Speaking Union.

Career

Day was called to the Bar in 1952, but practised only briefly. In his memoirs he recorded that he secured the acquittal of a lorry-driver accused of indecent exposure by persuading the magistrates that the man had been "shaking the drops from his person" after urinating, and by getting the man's young wife to testify, wearing a tight sweater, that she and her husband enjoyed a healthy love life.

Politics

In the 1959 UK General Election Robin Day stood as a Liberal Party candidate for Hereford but failed to win.

Media

Robin Day spent almost his entire working life in journalism. He rose to prominence on the new Independent Television News (ITN) from 1955, when he was the first British journalist to interview Egypt's President Nasser after the Suez Crisis.

On television, he presented Panorama and chaired the BBC's Question Time (1979–89), and on radio was presenter of The World at One from 1979 to 1987. His incisive and sometimes – by the standards of the day – abrasive interviewing style, together with his heavy-rimmed spectacles and trademark bow tie, made him an instantly recognisable and frequently impersonated figure over five decades.

He became known in British broadcasting as 'the Grand Inquisitor' for his abrasive interviewing of politicians, a style out of keeping with the British media's culture of deference to authority that prevailed during the early days of his career.

In 1958 he interviewed UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, in what the Daily Express called: "the most vigorous cross-examination a prime minister has been subjected to in public". The interview turned Macmillan into a television personality, and was probably the first time that British television became a serious part of the political process.

In the early 1970s, Robin Day was involved on BBC Radio, where he proved an innovator with It's Your Line (1970–76). This was a national phone-in programme that enabled ordinary people, for the first time, to put questions directly to the prime minister and other politicians (it later spawned Election Call). He also presented The World At One, from 1979 to 1987. In 1981, he was knighted for his services to broadcasting.

In October 1982, during an interview with the Secretary of State for Defence John Nott, pursuing cuts in defence expenditure, he posed the question: "But why should the public, on this issue, as regards the future of the Royal Navy, believe you, a transient, here-today and, if I may say so, gone-tomorrow politician, [a reference to Nott's announcement that he was to stand down at the next General Election] rather than a senior officer of many years?" Nott rose, removed his microphone, and said "I'm sorry, I'm fed up with this interview. Really, it's ridiculous" and walked off the set. Nott's autobiography in 2003 was called Here Today Gone Tomorrow: Recollections of an Errant Politician.

Robin Day was a regular fixture on all BBC Election Night programmes from the 1960s until 1987. After leaving Question Time, he moved to the new British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB) service where he presented the weekly political discussion programme Now Sir Robin. When BSB merged with Sky Television in November 1990, the programme continued to be broadcast on Sky News for a while.[3] On the night of the 1992 General Election, Sir Robin Day resumed his role as interviewer, this time on ITN's Election Night coverage, broadcast on ITV.

In the mid-90s, Sir Robin Day regularly contributed to the lunchtime Channel Four political programme Around the House and also presented Central Lobby for Central TV, the ITV franchise in the Midlands. The show was sometimes broadcast at the same time as his old programme, Question Time was being shown on BBC One.

The Apartheid Question

On February 25, 1988 British diplomat Patrick Haseldine was a member of the invited studio audience of BBC's Question Time which began transmission at 22:00. Fifteen minutes into the programme a student raised a question about that day's outlawing of 17 anti-apartheid organisations, and asked whether the British government was justified in its opposition of economic sanctions against South Africa in the face of calls for sanctions by Nelson Mandela, Bishop Tutu and by most of the European Community. The Question Time panel (Shirley Goodwin of the Health Visitors Association, Sir Russell Johnston - Liberal party spokesman on foreign affairs, Michael Meacher MP - Labour's shadow employment secretary and Michael Portillo MP junior minister at the DHSS) discussed the matter for nine minutes before the host Sir Robin Day asked if anyone in the audience had anything to add.

Without identifying himself, Haseldine intervened in the discussion and posed the following question:

- "Now that peaceful opposition has been outlawed in South Africa what active measures should Britain (the leading investor and major trading partner) take to avoid the seemingly inevitable violent upheaval which will ensue in South Africa?"

Sir Robin asked what measures Haseldine had in mind and, because no suggestions were forthcoming, put the question back to the panel. Their discussion was then prolonged by a further three minutes until 22:30 when Sir Robin asked the audience to raise their hands if they were in favour of economic sanctions against South Africa. Haseldine was on camera as a large majority of the audience voted for sanctions.

As a result of his Question Time appearance, Haseldine was suspended from his job in FCO's Defence Department for six months.[4]

After his return to the FCO, Patrick Haseldine wrote a letter to The Guardian on December 7, 1988 criticising PM Margaret Thatcher's policy towards South Africa. Upon publication of the letter, the FCO again suspended Haseldine, sent him a letter of complaint in accordance with diplomatic service regulation (DSR) number 20 and scheduled an internal FCO disciplinary hearing to take place on February 28, 1989. In advance of this hearing, Haseldine wrote on January 23, 1989 to Sir Robin Day asking for a video recording of the programme in which he had appeared. The editor of Question Time, Barbara Maxwell, sent him Sir Robin's own VHS copy together with a covering letter sympathising with his predicament.

Haseldine attended the FCO hearing with his solicitor, Pamela Walsh, and brought along the video – extracts of which were screened there. The disciplinary board's questioning was largely focused on the Guardian letter and Haseldine was repeatedly asked to divulge the source of the information in the letter. However, because he had been led to believe he was under an Official Secrets Act 1911 criminal investigation, he refused to be drawn on the matter lest he incriminate himself in advance of the trial.

The disclipinary board reported on March 7, 1989 to the Permanent Under-Secretary (PUS) at the FCO. In the unpublished report, the board said its task was defined solely by DSR 20 and the letter of complaint, which excluded consideration of the Question Time issue, and it agreed unanimously that the only appropriate penalty in Haseldine's case was enforced resignation or dismissal. On March 21, 1989 the PUS wrote to Haseldine saying he should resign by – or be dismissed on – April 4, 1989 when payment of his salary would cease.

Haseldine appealed against this decision in a letter dated March 22, 1989 to the foreign secretary, Sir Geoffrey Howe. At the start of the summer parliamentary recess on July 19, 1989 Sir Geoffrey Howe's private secretary, Stephen Wall, wrote informing Haseldine that his appeal had been rejected and that he should submit his resignation by August 2, 1989 or be dismissed on that date. He did not resign and the private secretary wrote again on August 4, 1989 (four days after Sir Geoffrey Howe had been demoted and replaced as foreign secretary by John Major) confirming that Haseldine had in fact been dismissed from the Diplomatic Service on August 2, 1989.[5]

Televising Parliament

For 25 years he campaigned tirelessly, and eventually successfully, for the televising of Parliament - not in the interests of television, but of Parliament itself. He claimed that he was the first to present the detailed arguments in favour, in a Hansard Society paper in 1963.[6]

Comedy portrayals

Monty Python's Flying Circus often used Sir Robin Day as a reference, including the 'Eddie Baby' sketch in which John Cleese turns to the camera and states: 'Robin Day's got a hedgehog called Frank.' In another sketch, Eric Idle said he was able to return his 'Robin Day tie' to Harrod's. He was also spoofed (as "Robin Yad") on The Goodies episode Saturday Night Grease. Sir Robin appeared as himself on an instalment of the Morecambe & Wise show, in which he berates Ernie Wise in character. Then Eric Morecambe, acting as a TV presenter, says, "Sadly, we've come to the end of today's "Friendly Discussion with Robin Day".

He was also frequently lampooned by the satirical TV programmme Spitting Image. In this, his most famous examples of lampoonery were his interviews with the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher and how she would always give an answer somewhat vague to the question, and his breathing difficulties which affected him later in life. "My name is Robin (deep breath) Day!"

Personal life

In 1965, Robin Day married Katherine Ainslie, an Australian law don at St Anne's College, Oxford, and they had two sons. The marriage was dissolved in 1986. One of the tragedies of his life was that his elder son never fully recovered from the effects of multiple skull fractures he sustained in a childhood fall.

In the 1980s, Day had a coronary bypass, and he suffered from breathing problems that were often evident when he was on the air. He had always fought against a tendency to put on weight. As an undergraduate, he weighed 108 kilos and claimed that, in the course of his life, he had succeeded in losing more weight than any other person.

Day had problems relating to women. The broadcaster Joan Bakewell recalled that whilst he was professional when in the office:

"Socially he was a menace. There was no subtlety in his manner: at office parties he would attack head on. 'Do the men you interview fancy you? Do they stare at your legs? Do they stare at your breasts? Do you sleep with many of them?' ... Whenever he loomed in sight, I made myself scarce"[7]

His funeral was a cremation service at Mortlake Crematorium. His ashes are interred near the south door of Whitchurch Canonicorum parish church in Dorset. The memorial stone has the words: "In loving memory of Sir Robin Day the Grand Inquisitor" upon it.

Day published two autobiographies: 'Day by Day' in 1975 and 'Grand Inquisitor' in 1989.

References

- ↑ "Obituary by Dick Taverne"

- ↑ "List of Old Brentwoods"

- ↑ "British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB)"

- ↑ "Suspended for speaking on BBC 'Question Time'"

- ↑ "Letter to The Guardian 7 December 1988"

- ↑ Robin Day, (1963) The Case for Televising Parliament (London: Hansard Society for Parliamentary Government)

- ↑ Joan Bakewell The Centre of the Bed: An Autobiography, 2003, Sceptre, p.234-5

External links

- Sir Robin Day: 1923–2000 from the BBC

- Tributes from the BBC

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here