Difference between revisions of "Esmé Howard"

(unstub, could need more deep contents) |

m (Text replacement - "He served as " to "He was ") |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

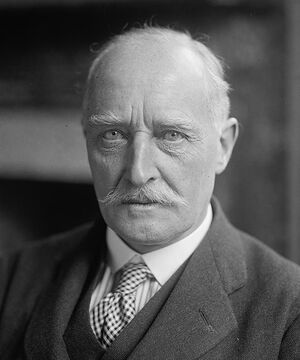

| − | '''Esmé William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Penrith'''<ref name="1939Obit">https://www.nytimes.com/1939/08/02/archives/lord-howard75-diplomatis-dead-formerly-british-ambassador-to-united.html?searchResultPosition=1</ref> was a British diplomat. He | + | '''Esmé William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Penrith'''<ref name="1939Obit">https://www.nytimes.com/1939/08/02/archives/lord-howard75-diplomatis-dead-formerly-british-ambassador-to-united.html?searchResultPosition=1</ref> was a British diplomat. He was [[British Ambassador to the United States]] between 1924 and 1930. He was one of Britain's most influential diplomats of the early part of the twentieth century. With a gift for languages and a skilled diplomat, Howard is described in his biography as an integral member of the small group of men who made and implemented British foreign policy between 1900 and 1930, a critical transitional period in Britain's history as a world power.<ref>B. J. C. McKercher, ''Esme Howard: A Diplomatic Biography'', CUP, 1989, revised ed., 2006</ref> |

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

Revision as of 15:06, 2 May 2022

(diplomat, deep state actor?) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 September 1863 |

| Died | 1 August 1939 (Age 75) |

| Alma mater | Harrow |

| Children | 5 |

| Spouse | Isabella Giustiniani-Bandini |

| Interests | • Milner Group • Imperial Federation League |

Esmé William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Penrith[1] was a British diplomat. He was British Ambassador to the United States between 1924 and 1930. He was one of Britain's most influential diplomats of the early part of the twentieth century. With a gift for languages and a skilled diplomat, Howard is described in his biography as an integral member of the small group of men who made and implemented British foreign policy between 1900 and 1930, a critical transitional period in Britain's history as a world power.[2]

Contents

Early life

Howard was born on 15 September 1863 at Greystoke Castle, near Penrith, Cumberland. He was the youngest son of the former Charlotte Caroline Georgina Long and Henry Howard, an MP for Steyning and New Shoreham.[3] His elder brothers were Henry Howard, an MP for Penrith, and Sir Stafford Howard, an MP for Thornbury and Cumberland East who served as Under-Secretary of State for India in 1886.

His paternal grandfather was Lord Henry Howard-Molyneux-Howard, the younger brother of Bernard Howard, 12th Duke of Norfolk. His maternal grandparents were Henry Lawes Long and Lady Catharine Long (a daughter of Horatio Walpole, 2nd Earl of Orford and sister of Horatio Walpole, 3rd Earl of Orford).[3]

Howard was educated at Harrow School.

Career

In 1885, he passed the Diplomatic Service examination, and was assistant private secretary to the Earl of Carnarvon as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland before being attached to the British Embassy in Rome. In 1888, he arrived in Berlin as the embassy's third secretary, and after retiring from the Diplomatic Service four years later, he was made assistant private secretary to the Earl of Kimberley, the Foreign Secretary at the time. Howard was a talented linguist who would spoke 10 languages and chose to retire from the diplomatic service in 1890 out of boredom.[4] For the next 13 years, Howard lived a life of irregular employment, spending his time prospecting for gold in South Africa, working as a researcher for the social reformer Charles Booth, making two lengthy trips to Morocco, working as the private secretary to Lord Kimberley in 1894–1895, frequently visiting his sister at her estate in Italy and running unsuccessfully as a Liberal candidate in the 1892 election.[5]

Greatly concerned with social problems, Howard had developed in the 1890s his "Economic Credo" about "co-partnership" under which he envisioned the state, businesses and unions working together for the improvement of the working classes.[6] Alongside his "Economic Credo", Howard believed in "Imperial Federation" under which Great Britain would be united in a federation that would take in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa.[6] In 1897, Howard set up a rubber plantation in Tobago, which was partly intended to finance a "co-partnership" business in Britain and partly to demonstrate to the British working class how the British empire benefited them financially.[6] Howard came from a cadet branch of one of the most famous Roman Catholic aristocratic families in England, but his grandfather had converted to the Church of England and Howard had been raised as an Anglican.[6] In 1898, Howard converted to Roman Catholicism to marry the Countess Isabella Giustiniani-Bandini, who came from a "black" Italian aristocratic family who supported the Papacy in its refusal to recognize the Italian state, unlike the "white" aristocrats who supported the Italian crown against the Catholic Church.[6] In 1903, following the failure of his rubber plantation together with a lack of public interest in his "Economic Credo" led to Howard rejoining the Diplomatic Service.[6]

Having fought in the Second Boer War with the Imperial Yeomanry, Howard became Consul General for Crete in 1903, and three years later was sent to Washington as a counsellor at the embassy there. Esme Howard was married to Isabella Giovanna Teresa Gioachina Giustiniani-Bandini of Venice. In 1906, the Liberals won the general election and Howard's old friend whom he had known since 1894, Sir Edward Grey became Foreign Secretary, which greatly benefited his career.[7] In 1908, he was appointed in the same role to Vienna, and that same year became Consul General at Budapest. Three years later, Howard was made Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Swiss Confederation,[8] and in 1913 he was transferred to Stockholm, where he spent the whole of the First World War. During World War I, Sweden leaned in a pro-German neutrality and Howard's time as the British minister in Stockholm was a difficult one with the Swedish leaders openly expressing their hopes for a German victory.[7] In an attempt to counter-act the pro-German sympathies of the Swedish elite, Howard sought to broaden his social contacts in Sweden, meeting with journalists, union leaders, businessmen, academics, clergymen, soldiers, and any local anglophiles in order to explain to them the British viewpoint.[9] In 1916, having already been appointed CMG and CVO ten years earlier, he was knighted as KCMG, becoming KCB three years later.

In 1919, Sir Esmé Howard was attached to the British delegation during the Paris Peace Conference, also being made British Civil Delegate on the International Commission to Poland. At the Paris Peace Conference, Howard was assigned to drafting sections of the Treaty of Versailles dealing with Poland.[7] That same year, he was sent to Madrid as ambassador there, arriving in August 1919.[7] Being appointed ambassador to Spain was a major step up in the Foreign Office, but Howard knew that Spanish issues were for the most part secondary to Lord Curzon, the Foreign Secretary.[9] In Howard's first annual summary as an ambassador from Madrid, Howard wrote: "In the first survey of the situation which I wrote after my arrival in this country I drew attention to three dominant factors in the state of affairs then existing: the activities of the juntas, the labor unrest and the bankruptcy of parliamentary institutions. These elements were perhaps not so immediately threatening as they then seemed but they are still elements of mischief".[10]

"A dose of fascismo"

Howard reported that the Spanish economy which depended upon exports of raw materials was collapsing due to the fall in commodity prices, that the politicians were incapable of providing leadership and King Alfonso XIII was not behaving as a constitutional monarch with the king trying to rule by intriguing with various politicians and generals instead of reigning.[11] Howard reported that in 1920 Spain had 1,060 strikes, and predicted that 1921 seemed likely to surpass that record.[11] Through Howard reported almost weekly bombings, assassinations and other "outrages" committed by extreme left-wing groups, in the main he blamed the confrontational relations between unions and businesses on the management, reporting that most Spanish corporations had little interest in compromise.[12] On 9 July 1920, the miners working for the British Rio Tinto company went on strike.[13] Howard's dispatches to London stating that the attitude of Walter Browning, Rio Tinto's manager in Spain, was harming Britain's image in Spain, led to the Foreign Office discreetly pressuring the CEO of the Rio Tinto company, Lord Denbigh, to settle the strike.[13] Much to Howard's satisfaction, the strike was ended in early 1921 with the Rio Tinto company giving wage increases to their Spanish miners.[14] In a sort of goodwill tour, Howard visited the Basque country in November 1920 where he toured mines, shipyards and foundries owned by British companies in an attempt to improve the British image with the Basque working class.[13]

In 1921, Howard had to play detective to find out the truth about reports about a major Spanish military disaster in the Rif mountains of Morocco.[15] After two weeks of seeking the truth, Howard reported to London that the Spanish defeat at the Battle of the Annual had been "decisive" and warned that the "Disaster of the Annual" as the battle was known in Spain had plunged the country into a crisis.[15] Howard reported that much fighting and huge expenditure of money that almost everything the Spanish had won in the Rif over the years had been lost in a matter of weeks and that the Spanish had been driven back in disorder to two coastal enclaves.[16] Howard predicated that the "Disaster of the Annual" would lead to "the growth of a chauvinistic Pan-Islamic movement" in North Africa and that the French would intervene rather than see their own position threatened in Algeria and French Morocco.[16] As the British did not wish for the French to control all of Morocco, Howard was ordered to see if it was possible if somehow the Spanish might rescue themselves from the war that they were losing in the Rif without the help of the French.[16] Howard wrote that in the aftermath of the "Disaster of the Annual", the Spanish people were obsessed with finding out who had sent General Manuel Fernández Silvestre into his ill-fated drive into the Rif and growing evidence was emerging that the King Alfonso had given the orders, predicating the future of the Spanish monarchy was at stake.[16]

Howard described Spain's colonial rule in Morocco as "a byword for cruelty, incompetence and corruption", but argued Britain had never let moral factors interfere "for the sake of larger and wider purposes of Policy", giving the example of British support for the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century despite the mistreatment of Christians in the Balkans.[17] Howard argued that the main concern for Britain was preventing France from expanding its influence in Morocco, which meant that Britain should support Spain wholeheartedly in the Rif war.[17]

In 1922, Howard suggested that to improve the image of Britain in Spain that several British intellectuals visit that country to give talks that might about the needed change in public relations and shortly afterwards, Hilaire Belloc visited Madrid to speak about Anglo-Spanish relations.[18] To formalize these exchanges, Howard together with the Duke of Alba founded the English Committee in Spain, which arranged for university students in both countries to take exchange courses and for various British intellectuals to undertake lecture tours in Spain.[18] In another initiative to improve Britain's image in Spain, Howard with the British-born Queen Victoria Eugenia established a relief fund for Spanish soldiers wounded in Morocco.[19] In the immediate post-war period, British decision-makers viewed France as too powerful and wanted a stronger Spain to check French power in the Mediterranean.

For this reason Howard welcomed the coup d'état of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in September 1923 as a force for order in Spain,[20], inspired by the "order" that Mussolini had created in Italy. Through Howard initially distrusted Primo de Rivera because of his stance on the Gibraltar issue, he quickly found from his discussions with Primo de Rivera that his main concern was winning the Rif war and he wanted British support for Spanish claims in Morocco against the French.[21]

Ambassador to Washington

In 1924, Howard returned to Washington as ambassador. Puzzled at first by the provincial background and eccentric style of President Calvin Coolidge, Howard came to like and trust the president, realizing that he was conciliatory and eager to find solutions to mutual problems, such as the Liquor Treaty of 1924 which diminished friction over smuggling.

Washington was greatly pleased when Britain ended its alliance with Japan. Both nations were pleased when in 1923 the wartime debt problem was compromised on satisfactory terms.[22]

Appointed GCMG and GCB in 1923 and 1928 respectively, he was created, on his retirement in 1930, Baron Howard of Penrith, of Gowbarrow in the historic county of Cumberland.[23] He died nine years later aged 75.[3]

Personal life

He married Lady Isabella Giustiniani-Bandini (daughter of Sigismondo Niccolo Venanzio Gaetano Francisco Giustiniani-Bandini, 8th Earl of Newburgh), of a branch of the Giustiniani by whom he had five sons, including:[1]

- Francis Philip Howard, 2nd Baron Howard of Penrith (1905–1999)

- Hon. Henry Anthony Camillo Howard (1913–1977), who was a journalist, military officer, and colonial leader in the Caribbean.

- Hon. Hubert John Edward Dominic Howard (1907–1987), who married Lelia Calista Ada Caetani (1913-1977), a daughter of Marguerite Caetani and Roffredo Caetani, Prince of Bassiano and last Duke of Sermoneta.[24]

Lord Howard died on 1 August 1939.[1]

References

- ↑ a b c https://www.nytimes.com/1939/08/02/archives/lord-howard75-diplomatis-dead-formerly-british-ambassador-to-united.html?searchResultPosition=1

- ↑ B. J. C. McKercher, Esme Howard: A Diplomatic Biography, CUP, 1989, revised ed., 2006

- ↑ a b c http://www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk/online/content/howard1930.htm

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 556.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 556-557.

- ↑ a b c d e f McKercher 1987, p. 557.

- ↑ a b c d McKercher 1987, p. 558.

- ↑ https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/28462/page/852

- ↑ a b McKercher 1987, p. 559.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 561.

- ↑ a b McKercher 1987, p. 562.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 562-563.

- ↑ a b c McKercher 1987, p. 564.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 565.

- ↑ a b McKercher 1987, p. 573.

- ↑ a b c d McKercher 1987, p. 574.

- ↑ a b McKercher 1987, p. 579-580.

- ↑ a b McKercher 1987, p. 560.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 580.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 555.

- ↑ McKercher 1987, p. 583-584.

- ↑ Benjamin D. Rhodes, "British diplomacy and the silent oracle of Vermont, 1923-1929'." Vermont History 50 (1982): 69-79.

- ↑ https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/33625/page/4427}

- ↑ https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/494837