Military Reaction Force

(Counter-terrorism) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | MRF |

| Formation | 1971 |

| Founder | |

| Extinction | 1973 |

| Headquarters | Palace Barracks, Holywood, Northern Ireland |

| Location | Northern Ireland |

| Type | hit squad |

| Staff | ~40 |

The Military Reaction Force (MRF) was a covert unit, or group of units, of the UK Army. It was set up in Northern Ireland in 1971. Its MRF acronym has given rise to a variety of explanations over the years. It was created by Frank Kitson in 1971 under the control of his 39 Infantry Brigade. The Four Square Laundry and Glen Road shooting incidents probably contributed to the decision to reorganise it in 1972 as the Special Reconnaissance Unit under the direct control of HQ Northern Ireland. " During its brief life, its operators gained both respect and notoriety. But it was too irregular, too flexible — indeed, too unmanageable."[1]

Contents

Creation

Mark Urban quotes Lord Carver as stating: "For some time various surveillance operations by soldiers in plain clothes had been in train, initiated by Frank Kitson when he commanded the the 39 Brigade in Belfast, some of them exploiting ex-members or supporters of the IRA."[2]

- On his appointment in 1970 to command 39 Brigade in Belfast, Kitson had received the approval of his superiors to set up the MRF. He recruited 'turned' IRA members , nicknamed the 'Freds', who were sent to live in a British Army married quarters at Palace Barracks in Holywood, east Belfast. The undercover unit started out as a handful of soldiers under the command of a captain who operated only in Brigadier Kitson's area of responsibility and were known by the nick name of the 'Bomb Squad'. The name Mobile Reconnaissance Force was only given several weeks after the soldiers had begun to operate.[3]

John Black allegations

A convicted loyalist using the pseudonym 'John Black' has claimed that the MRF was involved in the bombing of McGurk's bar on 4 December 1971, which killed 15 people.[4]

Seamus Wright

In the summer of 1972, the IRA discovered that one of its members, Seamus Wright, was working for the MRF:

- Under interrogation by Second Battalion staff, Wright admitted that all the time he had actually been in the company of a special military unit based at Palace barracks in Holyrood, Co. Down, where IRA suspects were taken for investigation before being interned. The unit was known by the initials MRF, which the IRA believed stood for Military Reconnaissance Force, a group subsequently alleged to have been involved in two drive-by shootings in the summer of 1972 that were blamed at the time on loyalist gangs. Wright admitted he had agreed to work for the MRF.[5]

Wright was allowed to return to Holyrood to glean more information:

- The IRA learned that the MRF operation was under the auspices of 39 Infantry Brigade and had been devised by Frank Kitson, who had left the province in April after having shaped the structure of the new force. The MRF was composed of several elements. The first was a group of regular soldiers who were divided into four-man units comprising a junior officer, a sergeant and two privates. They operated in plain clothes and drove civilian cars. The section to which Wright was attached was known as the 'Freds' and was composed of members of Republican and Loyalist paramilitary organisations who had been 'turned' by Special Branch and Army intelligence.[6]

Wright went on to implicate another IRA member Kevin McKee who gave the IRA further details about MRF operations.[7]

Activities

Four Square Laundry

McKee told the IRA that the MRF was operating the Four Square mobile laundry service in West Belfast to gather intelligence through surveillance and forensic testing on clothes.[8]

On 2 October 1972, the IRA attacked the Four Square laundry van on the Twinbrook estate, killing the driver, 21-year-old Sapper Ted Stuart. His colleague Lance Corporal Sarah Jane Warke of the Royal Military Police escaped.

At the same time, other IRA units attacked two offices linked to the MRF: one above a massage parlour at 397 Antrim Road, and the other at College Square East, but succeeded only in wounding a bystander.[9] According to Martin Dillon, the IRA did not realise that the massage parlour was itself an MRF intelligence-gathering operation.[10]

The IRA subsequently stated:

- "The Republican movement has been aware for a number of months of a Special British Army Intelligence Unit, code-named MRF. This unit, comprising picked men, has been operating under the guise of civilians. The unit was run by a Captain McGregor who used flats and offices in Belfast and ran a laundry service."[11]

Wright and McKee were subsequently killed and secretly buried by the IRA.[12]

Glen Road shooting

On the morning of 22 June 1972 shots were fired from a civilian car on the Glen Road, wounding two men on the street, and a third, Thomas Gerard Shaw, in the bedroom of a nearby house.

A year later, on 23 June 1973, the Belfast Telegraph reported the trial of 26-year-old Sergeant Clive Graham Williams, with Brian Hutton prosecuting.

- On the second day of the trial Sergeant Clive Graham Williams walked into the the witness box and identified himself as the commander of a unit of the Military Reaction Force attached to 39 Infantry Brigade. (Note his use of the word 'Reaction' rather than 'Reconnaissance' as in the official title given to the unit by the media, the Provos, the two double agents and Army statements released after the Four-Square attacks. Was the designation 'Military Reaction Force' an error on the part of Williams, or was it the Army's term for this elite grouping, or was it a term which defined a role for one of the sections within the Military Reconnaissance Force? [13]

Williams was found not guilty by an 11 to 1 majority verdict. Charges had previously been dropped against Captain James McGregor who had been in the car with him, and who had previously been named to the IRA as a leading MRF member by Wright and McKee.[14]

Other plain clothes shooting incidents

Martin Dillon cites a number of other incidents in Belfast in 1972 that may have been linked to the MRF:[15]

- - The killing of Patrick McVeigh in Andersonstown by plain-clothes soldiers on 13 May 1972.

- - The shooting of Jerry and John Conway by plain-clothes soldiers on the Springhill estate several weeks earlier.

- - A shooting incident involving a plain-clothes army patrol on the Shankill in May 1972.

- - The killing of nineteen-year-old Daniel Rooney and wounding of 18-year-old Brendan Brennan by a plain-clothes army patrol in the St James district on 27 September 1972. Lieutenant-Colonel Robin Evelegh of the Royal Green Jackets subsequently produced a car with bullet holes that he claimed Rooney and Brennan had fired on. A statement asserting Rooney's innocence was read at local Catholic churches on 1 October.

RUC relations

Martin Dillon has suggested that RUC detective work played a significant role in exposing the MRF's activities.

- A Special Branch officer told me that their 'fingerprints were not on that period.' They all agreed that the MRF's operations were amateurish and not tightly controlled.[16]

Wilson Briefing

The history of the MRF was outlined in a briefing submitted to Prime Minister Harold Wilson ahead of a meeting with Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave on 5 April 1974.

- “Plain-clothes teams, initially joint RUC/army patrols, have operated in Northern Ireland since the IRA bombing campaign in Easter 1971.

- “Later in 1971 the teams were reformed and expanded as Military Reaction Forces (MRFs) without RUC participation.

- “In 1972 the operations of the MRF were brought under more centralised control and a higher standard of training achieved by establishing a Special Reconnaissance Unit (SRU) of 130 with all ranks under direct command of HQNI.[17].

Robin Ramsay commented:

- For those two lines read, 'After the MRF were exposed as driving around shooting at alleged members of the IRA, we had to get some kind of grip on the situation and broke up MRF.'

- This is the first official explanation of what the initials MRF stood for that I have seen.[18]

SAS assessment

Ramsay's conclusion is supported by the account of former SAS soldier Ken Connor, who states that he was part of a three man team sent to assess the MRF , which he refers to as the Military Reconnaissance Force, in the wake of the Four Square Laundry episode.

- It soon became apparent that its cover was blown and the group of people running it were so out of control that it had to be disbanded at once.

- Without reference to each other, we all produced the same recommendation: it's been a useful tool, but it's well past it's sell-by date. Get rid of it, acquire the needed skills, then reform it in a different guise.

- The result was 14 Int - the Fourteenth Intelligence Company.[19]

In this instance, 14 Intelligence Company would seem to be a cover name for the Special Reconnaissance Unit.

People

- Captain James McGregor

- Sergeant Clive Graham Williams

- Lance-Corporal Sarah Jane Warke

- Sapper Ted Stuart

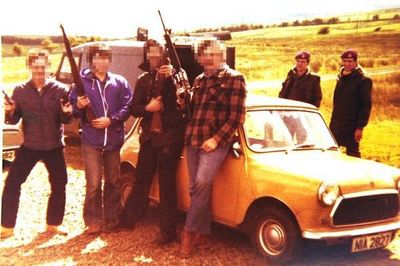

Alleged 'Freds'

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:Countergangs1971-76.pdf | book | November 2012 | Margaret Urwin |

References

- ↑ https://sofrep.com/91450/military-reaction-force-northern-ireland/

- ↑ Big Boys Rules by Mark Urban, Faber and Faber, 1992, p.35.

- ↑ Big Boys Rules by Mark Urban, Faber and Faber, 1992, p.36.

- ↑ How Britain created Ulster's murder gangs, by Neil Mackay, Sunday Herald,27 January 2007.

- ↑ A Secret History of the IRA, by Ed Moloney, Penguin, 2002, p119.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, p37.

- ↑ A Secret History of the IRA, by Ed Moloney, Penguin, 2002, p119. The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, p38.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p39.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p29-32.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p44.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p31.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p31.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p46.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p48.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, pp53-55.

- ↑ The Dirty War, by Martin Dillon, Arrow Books, 1991, p56.

- ↑ National Archives PREM 16/154, quoted in Irish were lied to about SAS, by Tom Griffin, Daily Ireland, 5 June 2006.

- ↑ View from the Bridge, by Robin Ramsay, Lobster magazine 52, Winter 2006/7.

- ↑ Ken Connor, Ghost Force, The Secret History of the SAS, Cassell & Co, 1998, p269.