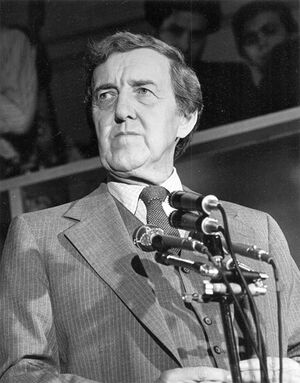

Edmund Muskie

( Lawyer) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Edmund Sixtus Muskie 1914-03-28 Rumford, Maine, United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1996-03-26 (Age 81) Washington DC, United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | • Bates College • Cornell Law School | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Jane Gray Muskie | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of | Action Council for Peace in the Balkans, Council on Foreign Relations/Historical Members | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Democratic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

His legislative work during his career as a Senator coincided with an expansion of modern liberalism in the United States. ran for President several times, sabotaged by Richard Nixon in 1972.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Edmund Sixtus Muskie was an American statesman and political leader who was made 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter, a United States Senator from Maine from 1959 to 1980, the 64th Governor of Maine from 1955 to 1959, and a member of the Maine House of Representatives from 1946 to 1951. He was the Democratic Party's candidate for Vice President of the United States in the 1968 presidential election, alongside Hubert Humphrey.

Contents

Early Life

Born in Rumford, Maine, he worked as a lawyer for two years before serving in the United States Naval Reserve from 1942 to 1945 during World War II.

Governor of Maine

Upon his return, Muskie was in the Maine State Legislature from 1946 to 1951, and unsuccessfully ran for the mayor of Waterville. Muskie was elected the 64th Governor of Maine in 1954 under a reform platform as the first Maine Democratic Party governor in almost 100 years. Muskie pressed for economic expansionism and instated environmental provisions. Muskie's actions severed a nearly 100-year Republican stronghold and led to the political insurgency of the Maine Democrats.

Senator

His legislative work during his career as a Senator coincided with an expansion of modern liberalism in the United States. He promoted the 1960s environmental movement which lead to in the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970 and Clean Water Act of 1972. Muskie supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the creation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and opposed Richard Nixon's "Imperial Presidency" by advancing New Federalism. Muskie ran with Humphrey against Nixon in the 1968 presidential election, losing the popular vote by 0.7 percentage points—one of the narrowest margins in U.S. history. He would go on to run in the 1972 presidential election where he secured 1.84 million votes in the primaries coming in fourth out of 15 contesters. The release of the forged "Canuck letter" derailed his campaign and sullied his public image with Americans of French-Canadian descent.

After the election, he returned to the Senate where he gave the 1976 State of the Union Response. Muskie was first chairman of the new Senate Budget Committee from 1975 to 1980 where he established the United States budget process.

He ultimately approved of and shaped the formation of the modern United States budget process.[1][2][3] Upon his retirement from the Senate, he became the 58th U.S. Secretary of State under President Carter. His tenure as Secretary of State was one of the shortest in modern history. His department negotiated the release of 52 Americans concluding the Iran hostage crisis. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Carter in 1981 and has been honored with a public holiday in Maine since 1987.

Canuck letter

The Canuck letter was a forged letter to the editor of the Manchester Union Leader, published February 24, 1972, two weeks before the New Hampshire primary of the 1972 United States presidential election. It implied that Senator Edmund Muskie, a candidate for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination, held prejudice against Americans of French-Canadian descent.

Reportedly the successful sabotage work of Donald Segretti and Ken W. Clawson;[4][5] in a childish scrawl with poor spelling, the author of the Canuck letter claimed to have met Muskie and his staff in Florida, and to have asked Muskie how he could understand the problems of African Americans when his home state of Maine has such a small black population, to which a member of Muskie's staff was said to have responded, "Not blacks, but we have Canucks" (which the letter spells "Cannocks"); the author further claims that Muskie laughed at the remark. While an affectionate term among Canadians today, "Canuck" is a term often considered derogatory when applied to Americans of French-Canadian ancestry in New England; a significant number of New Hampshire voters were of such ancestry.[6]

On October 10, 1972, FBI investigators revealed that the Canuck letter was part of a dirty tricks campaign against Democrats orchestrated by the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP) (later derisively nicknamed CREEP).[7]

The letter's immediate effect was to compel the candidate to give a speech in front of the newspaper's offices, subsequently known as "the crying speech".[8] The letter's indirect effect was to contribute to the implosion of Muskie's candidacy.

The crying speech

On the morning of February 26, two Saturdays before the March 7 primary, Muskie delivered a speech in front of the offices of the Union Leader, calling its publisher, William Loeb, a liar and lambasting him for impugning the character of Muskie's wife, Jane. Newspapers reported that Muskie cried openly: David Broder of The Washington Post had it that Muskie "broke down three times in as many minutes"; David Nyhan of The Boston Globe had Muskie "weeping silently".[9] The CBS Evening News showed Muskie's face contorted with emotion. Muskie maintained that if his voice cracked, it cracked from anger; Muskie's antagonist was the same editor who referred to him in the 1968 election as "Moscow Muskie", and called him a flip-flopper. The tears, Muskie claimed, were actually snow melting on his face. Jim Naughton of The New York Times, standing immediately at Muskie's feet, could not confirm that Muskie cried.

Denunciation

Whether true or false, fear of Muskie's alleged unstable emotional condition led some New Hampshire Democrats to defect to George McGovern. Muskie's winning margin, 46% to McGovern's 37%, was smaller than his campaign had predicted. The bounce and second-place finish led the McGovern campaign to boast of its momentum. By the time of the Florida primary, with McGovern clearing other left-leaning candidates from the field, Muskie's campaign was dead.

Washington Post staff writer Marilyn Berger reported that Nixon White House staffer Ken Clawson had bragged to her about authoring the letter. Clawson denied Berger's account. In October 1972, FBI investigators asserted that the Canuck Letter was part of the dirty tricks campaign against Democrats orchestrated by the Committee for the Re-Election of the President.[10] Loeb, the publisher of the Manchester Union Leader, maintained that the letter was not a fabrication, but later admitted to having some doubt, however, after receiving another letter claiming that someone had been paid $1,000 to write the Canuck Letter. The purported author, Paul Morrison of Deerfield Beach, Florida, was never found.

The authorship of the letter is covered at length in the 1974 book All the President's Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein and its 1976 film adaptation.

References

- ↑ https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/yY5IWOkRONc Ghostarchive

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/14/archives/budget-balancers-warned-by-muskie-he-says-amendment-would-result-in.html

- ↑ http://www.bates.edu/archives/edmund-s-muskie-and-his-legacy/research-help/chronology-of-muskies-life-and-work

- ↑ Bernstein, Carl; Woodward, Bob (2005). All the President's Men. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-89441-2. https://archive.org/details/allpresidentsmenbern

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/watergate/articles/101072-1.htm

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/allpresidentsmenbern/page/129

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=y7RoHrgX7yAC&pg=PT289

- ↑ The Crying Speech

- ↑ http://articles.philly.com/1987-03-08/news/26220294_1_ed-muskie-manchester-union-leader-tears

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/watergate/articles/101072-1.htm