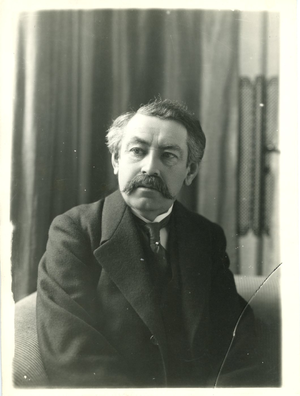

Aristide Briand

(Politician) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 March 1862 Nantes |

| Died | 7 March 1932 (Age 69) Paris |

| Alma mater | Faculty of Law of Paris |

| Party | SFIO, PRS |

French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliation politics during the interwar period (1918-1939).

| |

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliation politics during the interwar period (1918-1939).

In 1926, he received the Nobel Peace Prize along with German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann for the realization of the Locarno Treaties, which aimed at reconciliation between France and Germany after the First World War.[1][2] To avoid another worldwide conflict, he was instrumental in the agreement known as the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1929, as well to establish a "European Union" in 1929.[3] However, all his efforts were compromised by the rise of nationalistic and revanchist ideas like Nazism and Fascism following the Great Depression.

Contents

World War 1

At the end of August 1914, following the outbreak of the First World War, Briand again became Minister of Justice when René Viviani reconstructed his ministry. In the winter of 1914-15 Briand was one of those who pushed for an expedition to Salonika, in the hope of helping Serbia, and perhaps bringing Greece, Romania, Bulgaria and Italy into the war as a pro-French bloc, which would also act as a barrier to future Russian expansion in the Balkans. He got on well with Lloyd George, who was also, contrary to military advice, keen for operations in the Balkans, and had a long talk with him on 4 February 1915.[4]

Political work after the First World War

After the First World War, Briand was one of the supporters of international peace efforts and the League of Nations. After taking over government affairs again in 1921, he resigned again on January 22, 1922, because the security pact between France and Great Britain was not ratified at the Cannes Conference and also Briand's criticism of the harsh conditions of the Peace Treaty of Versailles towards the German Reich encountered resistance from the population.

From 1925 to 1929 Briand remained foreign minister in 14 successive governments and advocated disarmament, rapprochement with Germany and international cooperation. In 1925 he was the chief architect of the Locarno Treaties. In 1926 he received the Nobel Peace Prize for this together with the German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann, with whom he was a fellow member of the Freemasons. He was also the 1928 initiator of the Briand-Kellogg Pact, a treaty on the mutual renunciation of war between states.

Support for Zionism

From 1915, Aristide Briand expressed his support for Zionism. On October 22, 1926, he received Chaim Weizmann, President of the World Zionist Organization[5]. He was also named honorary president of the pro-Zionist Association France-Palestine[6].

In 1926, he wrote in a message sent to the France-Palestine association:

- "It is certainly desirable that the Jews know that they will be able to find in Palestine a refuge from the bad treatment which too often overwhelms them, a national hearth to shelter their memories and their hopes: we said it in San-Remo. [...] The national home is a remedy, doubtless still imperfect and yet necessary, for an evil which would have cured itself if no State had made a difference between its Jewish nationals and the others, if all the Jews had shown themselves ready to consider themselves citizens of the States where they had settled; if the teachings of the Sanhedrin meeting in Paris in 1807 had been understood everywhere, in short, if everyone had rallied to the striking formula of the Emperor Napoleon: "I want the Jews to find Jerusalem in France" . Democratic nations can therefore only praise you for having wanted to try this generous experiment and congratulate themselves on the success which already crowns your efforts. You are right to wish that the French Jews, who found Jerusalem in France, and with them all the other French people, knowing how to help with their help those of the sons of Israel who had not had this happiness, had to turn to ancient Jerusalem.

After his death, the KKL took the initiative to plant a forest in Palestine in his memory, an initiative sponsored by the President of the Republic Albert Lebrun and the former President of the Council Edouard Herriot.[7]

Briand Plan for European union

As foreign minister Briand formulated an original proposal for a new economic union of Europe. Described as Briand's Locarno diplomacy and as an aspect of Franco-German rapprochement, it was his answer to Germany's quick economic recovery and future political power. Briand made his proposals in a speech in favor of a European Union in the League of Nations on 5 September 1929, and in 1930, in his "Memorandum on the Organization of a Regime of European Federal Union" for the Government of France.[8]

The idea was to provide a framework to contain France's former enemy while preserving as much of the 1919 Versailles settlement as possible. The Briand plan entailed the economic collaboration of the great industrial areas of Europe and the provision of political security to Eastern Europe against Soviet threats. The basis was economic cooperation, but his fundamental concept was political, for it was political power that would determine economic choices. The plan, under the Memorandum on the Organization of a System of European Federal Union, was in the end presented as a French initiative to the League of Nations. With the death of his principal supporter, German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann, and the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, Briand's plan was never adopted but it suggested an economic framework for developments after World War II that eventually resulted in the European Union.[9]

References

- ↑ https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/articles/lundestad-review/index.html

- ↑ https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1926/index.html

- ↑ Leboutte, René (2008). Histoire économique et sociale de la construction européenne (in French). Peter Lang. p. 33.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge University Press. p.100 &108

- ↑ Mr ARISTIDE BRIAND DECLARE SES SYMPATHIES POUR L'OEUVRE SIONISTE archived,

- ↑ « Le Comité France-Palestine rend hommage à M. Briand archived

- ↑ https://www.nli.org.il/he/newspapers/isr/1932/03/18/01/article/5

- ↑ Briand, Aristide (1930-05-01). Memorandum on the Organization of a System of Federal European Union. France. Ministry of Foreign Affairs - via World Digital Library. Retrieved 2014-06-19

- ↑ D. Weigall and P. Stirk, eds., The Origins and Development of the European Community (Leicester University Press, 1992), pp. 11–15 ISBN 0718514289.