Document:Why the NHS Covid-19 contact tracing app failed

| On 18 June 2020, Matt Hancock announced that the planned centralised NHS Covid-19 contact tracing app, which has been trialled on the Isle of Wight and downloaded by tens of thousands of people, has been ditched in favour of a decentralised system developed by Google and Apple. |

Subjects: NHSX, Dido Harding, Matthew Gould, Matt Hancock, Marc Warner, Ben Warner, Dominic Cummings

Source: WIRED (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Matt Hancock has had another app catastrophe.[1] England’s planned contact tracing app, which has been trialled on the Isle of Wight and downloaded by tens of thousands of people, has been ditched in favour of a system developed by Google and Apple.

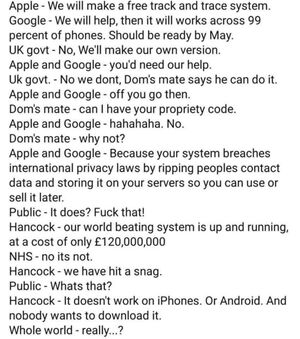

The reversal, first reported by the BBC and later confirmed by the government, follows months of delays for the home-brewed app and difficulties surrounding its implementation. It also makes England the latest in a string of countries to ditch a centralised system in favour of a decentralised one supported by two Silicon Valley giants. That club also includes Germany, Italy and Denmark.

Through testing the app has been found to have flaws detecting iPhones. Apple’s iOS pushed the app to the background and as a result it could only detect four per cent of iPhones it came into contact with, compared with 75 per cent of Androids. In contrast, iPhones running the Apple-Google system spotted 99 per cent of handsets.

The development of the app has taken months and consumed NHS resources as well as the work of private companies contracted to help build the system. The app was first mooted in mid-March, the week before the UK entered lockdown. It was reported NHSX, a group introduced to help the NHS develop new technology, would be behind the app.[2]

As a result of the app’s failure the government now says it will move to working with the Apple and Google model. Dido Harding, the head of the wider track and trace programme and Matthew Gould, the boss of NHSX, said they wanted a future app to be able to allow people to order a test and access the “right guidance and advice”. There is no guarantee that a future app will be capable of running automated contact tracing.

Hancock also confirmed that NHSX had started building an app on Apple and Google’s system in May, however his own government department told The Mirror at the time that another app wasn’t being created. The government has not revealed how much the development of the dud app cost but said the efforts were not in vain. They claim the system developed by the NHS could more accurately detect the distance between phones communicating via Bluetooth than the system developed by Apple and Google.

However, problems with the app developed in England have plagued it throughout. Here’s what went wrong with the app.

The technology

There has never been any evidence that contact tracing apps – of any sort – are hugely effective. “There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of digital contact tracing as an effective technology to support the pandemic response,” a rapid evidence review by the Ada Lovelace Institute in April concluded.[3]

However, not using APIs created by Apple and Google always carried significant risk. The system created by the big tech firms lets Bluetooth run seamlessly in the background. Countries like England that chose to forge their own path had to work around restrictions in Android and iOS, something that NHSX has belatedly realised is simply not possible.

On April 29, almost 200 cybersecurity and privacy experts called for the system to be properly scrutinised and argued that a centralised app was open to mission creep, with surveillance being introduced with new, more intrusive features.[4]

At the start of May, Australia’s contact tracing app, which wasn’t using Apple and Google’s system, was reported not to work with iPhones.[5] More recent figures reveal it only works in one in four occasions and the country is now trialling the Apple and Google model instead.

Analysis of the NHSX contact tracing app, which uses a different system to Australia, showed developers had implemented some clever workarounds to keep the app working in the background on iPhones.[6] “It appears that this is done through use of a series of clever workarounds using keepalives and notifications,” an analysis by software firm Reincubate found. But the latest government announcement shows the approach taken hasn’t succeeded.

There have also been continued concerns around the NHSX app’s impact on phone battery life. People on the Isle of Wight who have tested the app have complained about incorrect notifications, glitches and bugs within the app, causing some people to uninstall it from their devices.

Speed

The NHSX app has been delayed again and again. Hancock and Gould both initially said the app would be launched by mid-May but this slipped a few times before the pivot to the Apple and Google approach was confirmed. At one point, Hancock said it would would be a “civic duty” to download the app and it would play an essential role in tracking and limiting the spread of Covid-19.

By the start of June, the app’s launch date was pushed back again, this time by a few weeks. Hancock said it was now the “the cherry on the cake” of wider contact tracing efforts. The manual contact tracing scheme, employing 25,000 people, launched at the end of May. During the delays, lockdown rules rules in England were eased.[7]

Data collection

While the NHSX app doesn’t collect any specific information about users – such as their locations through GPS, or names and email addresses – people have been worried about government surveillance. The government decided to avoid the Apple and Google decentralised model in favour of a centralised model that can hold the pseudonymised details of who people have been in contact with and postcode areas.

Health officials have argued they prefer this approach because they would have been able to collect data that shows “hotspots” of coronavirus outbreaks and as a result send extra resources to hospitals and NHS organisations. One risk with a centralised system is the potential for people to be reidentified if extra information, such as location, was added to the app in the future. Secret NHS files about the app’s development were also left exposed in an unlocked Google Drive folder.[8]

The day before the app u-turn James Bethell, the minister for innovation at the Department of Health and Social Care, said there were still big concerns about people’s privacy and data collection. “If we didn't quite get it right the first time round, we might poison the pool and close down a really important option for the future,” he said.

Interoperability

As lockdowns have been eased the potential for international travel has increased. Countries that don’t have contact tracing apps that work with those from other nations could be faced with harder negotiations when it comes to allowing people to move across borders. Apps using the Apple and Google protocol will be able to communicate with each other more easily than with those that don’t use the standard.

On June 17, the European Commission published technical guidelines agreed by EU countries for how apps could work together.[9] “Member states will already be able to update apps to permit information exchange between national, decentralised apps as soon as they are technically ready,” the Commission said. Countries, such as England, that were planning on using centralised systems, would have to wait for extra technical work to be completed.

References

- ↑ "Matt Hancock MP has launched an app. And he wants all your data"

- ↑ "NHS developing coronavirus contact tracking app"

- ↑ "Exit through the App Store? Should the UK Government use technology to transition from the COVID-19 global public health crisis"

- ↑ "Joint Statement by scientists and researchers working in the UK in the fields of information security and privacy"

- ↑ "Covidsafe app is not working properly on iPhones, authorities admit"

- ↑ "A technical deep-dive into the NHS COVID-19 contact tracing app"

- ↑ "When will lockdown end? The UK's lockdown rules, explained"

- ↑ "Secret NHS files reveal plans for coronavirus contact tracing app"

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Member States agree on an interoperability solution for mobile tracing and warning apps"