Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

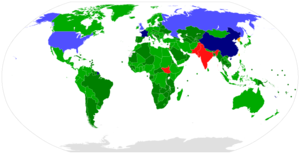

Parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty | |

| Type | treaty |

| Founded | 1968 |

| Author(s) | |

| The treaty concerning the spread of nuclear weapons technology | |

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament.[1]

Contents

Origins

Opened for signature in 1968, the treaty entered into force in 1970. As required by the text, after twenty-five years, NPT Parties met in May 1995 and agreed to extend the treaty indefinitely.[2] More countries have adhered to the NPT than any other arms limitation and disarmament agreement, a testament to the treaty's significance. As of August 2016, 191 states have adhered to the treaty, though North Korea, which acceded in 1985 but never came into compliance, announced its withdrawal from the NPT in 2003, following detonation of nuclear devices in violation of core obligations.[3] Four UN member states have never accepted the NPT, three of which are thought to possess nuclear weapons: India, Israel, and Pakistan. In addition, South Sudan, founded in 2011, has not joined.

The 5 Nuclear Weapon States

The treaty defines nuclear-weapon states as those that have built and tested a nuclear explosive device before 1 January 1967; these are: the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China. Four other states are known or believed to possess nuclear weapons: India, Pakistan, and North Korea have openly tested and declared that they possess nuclear weapons, while Israel is deliberately ambiguous regarding its nuclear weapons status.

The logic

The NPT is often seen to be based on a central bargain:

the NPT non-nuclear-weapon states agree never to acquire nuclear weapons and the NPT nuclear-weapon states in exchange agree to share the benefits of peaceful nuclear technology and to pursue nuclear disarmament aimed at the ultimate elimination of their nuclear arsenals.

The treaty is reviewed every five years in meetings called Review Conferences of the Parties to the Treaty of Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Even though the treaty was originally conceived with a limited duration of 25 years, the signing parties decided, by consensus, to unconditionally extend the treaty indefinitely during the Review Conference in New York City on 11 May 1995, culminating successful US government efforts led by Ambassador Thomas Graham Jr.

Nuclear proliferation

At the time the NPT was proposed, some commentators[Who?] were predicting 25–30 nuclear weapon states within 20 years. Instead, over forty years later, five states are not parties to the NPT, and they include the only four additional states believed to possess nuclear weapons.[4] Several additional measures have been adopted to strengthen the NPT and the broader nuclear nonproliferation regime and make it difficult for states to acquire the capability to produce nuclear weapons, including the export controls of the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the enhanced verification measures of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Additional Protocol.

Criticism

Critics argue that the NPT cannot stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons or the motivation to acquire them. They express disappointment with the limited progress on nuclear disarmament, where the five authorised nuclear weapons states still have 22,000 warheads in their combined stockpile and have shown a reluctance to disarm further. Several high-ranking officials within the United Nations have said that they can do little to stop states using nuclear reactors to produce nuclear weapons.[5]

Related Documents

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:Labour Built the Bomb | Article | 10 July 2017 | Bill Ramsay | The prompt for this short essay is not Labour's nuclear legacy: it is what took place in the UN General Assembly last Friday when the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty passed into international law. |

| Document:Russia is deploying nuclear weapons in Belarus. NATO shouldn’t take the bait | Article | 24 April 2023 | Nikolai Sokov | Moscow regards the United States and Europe as parties to the war; Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov declared that Russia and the United States are in a “hot phase” of war. These statements elevate the Russian war against Ukraine to the category of a “regional conflict” according to the 2000 and subsequent Russian Military Doctrines – a category that allows for limited use of nuclear weapons. |

References

- ↑ "UNODA - Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)". un.org. Retrieved 2016-02-20.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "Decisions Adopted at the 1995 NPT Review & Extension Conference - Acronym Institute".Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)" (PDF). Defense Treaty Inspection Readiness Program - United States Department of Defense. Defense Treaty Inspection Readiness Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|deadurl=(help)Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto"). - ↑ Graham, Jr., Thomas (November 2004). "Avoiding the Tipping Point". Arms Control Association.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ Benjamin K. Sovacool (2011). Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, World Scientific, pp. 187–190.