Difference between revisions of "Grigori Rasputin"

(saving draft. I'll clean & add references later) |

m (wording) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

|alma_mater= | |alma_mater= | ||

}} | }} | ||

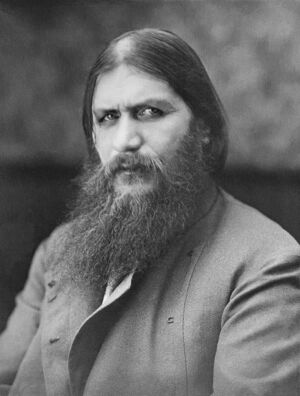

| − | '''Grigory Efimovich Rasputin''' was a Russian mystic and healer. He was the confidant of [[Alexandra Feodorovna]], wife of Emperor [[Nicholas II]], which allowed him to exercise a strong influence within the Russian imperial court. He was assassinated by British | + | '''Grigory Efimovich Rasputin''' was a Russian mystic and healer. He was the confidant of [[Alexandra Feodorovna]], wife of Emperor [[Nicholas II]], which allowed him to exercise a strong influence within the Russian imperial court. He was assassinated in 1916 by Russian aristocrats and agents of the British [[Secret Intelligence Service]] under the direction of agent [[Oswald Rayner]], who shot him at point blank range. The British feared that Rasputin wanted to withdraw the Russian troops engaged in the [[First World War]] against [[Germany]]. |

| − | Originally from the Western Siberia, he | + | Originally from the Western Siberia, he presented himself as a <i>strannik</i>, a wandering mystical pilgrim, and claimed to be <i>starets</i> and prophet. While no ecclesiastical source attests to his membership of any religious order, he asserts his loyalty to the [[Russian Orthodox Church]] but is suspected of belonging to the sect of the [[Khlysts]]. The most generally accepted hypothesis is that he is above all was an adventurer, presenting himself as an itinerant pilgrim, and endowed with a great power of seduction, in no small part due to his intense gaze. |

| − | + | Already renowned as a healer, in 1905 he was invited for the first time by the imperial couple to the bedside of their son, [[Alexis Romanov|Alexis]], heir to the throne suffering from [[hemophilia]]. Rasputin gained steadily more influence, especially during [[World War 1]]. The Czarina and his family considered him a healer, a mystic, even a prophet. His enemies described him as a debauched charlatan, driven by an inordinate sexual appetite and even as a [[spy]]. He thus participates in the discrediting the imperial family and constitutes one of the elements of the fall of the [[Romanovs]]. He was assassinated following a plot fomented by members of the aristocracy in collaboration with the British [[Secret Intelligence Service]]. | |

Some gray areas remain about his life and influence, his biography being mostly based on biased testimonies, in part fueled by anti-monarchist propaganda, rumors and legends. After his death, his myth inspired many writers and artists. Long demonized, he subsequently enjoyed a less unfavorable opinion in Russia than during his lifetime. | Some gray areas remain about his life and influence, his biography being mostly based on biased testimonies, in part fueled by anti-monarchist propaganda, rumors and legends. After his death, his myth inspired many writers and artists. Long demonized, he subsequently enjoyed a less unfavorable opinion in Russia than during his lifetime. | ||

==With the imperial family== | ==With the imperial family== | ||

| − | The Czarina, long worried about not giving a male heir to the crown, had become accustomed to attracting around her many mystics and healers. | + | [[image:Alexandra Feodorovna with Rasputin, her children and a governess.jpg|thumb|Alexandra Feodorovna with Rasputin, her children and a governess.]] |

| − | + | The Czarina, long worried about not giving a male heir to the crown, had become accustomed to attracting around her many mystics and healers. Through the Grand Duchess Militza and her sister, Grand Duchess Anastasia , the "starets" is presented to the imperial family on November 1, [[1905]]. Tsarevich Alexis suffering from hemophilia, Rasputin asked to be taken to the bedside of the young patient who was bedridden after a fall, which caused a huge hematoma in the knee. He lays his hands on him, tells him several Siberian tales and thus manages, it seems, to stem the crisis and relieve him after a few days. According to some, this could be explained by the simple fact that the medicine of the time ignored the properties of the [[aspirin]] which was given to the young patient. This drug is an anticoagulant, an aggravating factor in hemophilia. The simple fact of sweeping the table and throwing away the "remedies" given to the patient - including aspirin - could only have improved his condition.<ref>Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2012). Rasputin: The Untold Story. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-23985-8.</ref> | |

| − | Through the Grand Duchess Militza and her sister, Grand Duchess Anastasia , the "starets" is presented to the imperial family | ||

The parents are seduced by the healing gifts of this humble "muzhik" who also seems to have that of prophecy. Alexandra convinced herself that Rasputin was a messenger from God, that he represented the union of the Tsar, the Church and the people and that he had the capacity to help her son with his healing gifts and his prayer. | The parents are seduced by the healing gifts of this humble "muzhik" who also seems to have that of prophecy. Alexandra convinced herself that Rasputin was a messenger from God, that he represented the union of the Tsar, the Church and the people and that he had the capacity to help her son with his healing gifts and his prayer. | ||

| − | His reputation | + | His reputation allowed Rasputin to make himself indispensable; he very quickly gathers a considerable influence over the imperial couple. He is invited to many social gatherings, and got to know many wealthy women. Rasputin fascinates: his piercing gaze is difficult to resist for his admirers, many give in to his hypnotic charm and take him for a lover and/or a healer. |

[[image:Rasputin Photo.jpg|thumb|Rasputin and his "admirers" in 1914.]] | [[image:Rasputin Photo.jpg|thumb|Rasputin and his "admirers" in 1914.]] | ||

| − | + | Although not enriching himself, he continued to lead a dissolute life of drinking and debauchery, retaining his greasy hair and tangled beard<ref>Revière, Perez et Grossmann, « Les Secrets de la mort de Raspoutine », Io - Martange, série « L'Ombre d'un doute, 13 », 28e min 50 s.</ref>. He throws parties in his apartment, where sex dominates - up to ten sexual relations a day<ref name=Vladimir>Vladimir Fédorovski, Le Roman de Raspoutine, Éditions du Rocher, 2011, 220 p.</ref> - and alcohol. He preaches his doctrine of redemption through sin among the ladies, eager to go to bed with him to practice his teaching, which they see as an honor. | |

| − | + | After the [[revolution of 1905]], Rasputin came up against the President of the Council [[Piotr Stolypin]]. Appointed in mJuly 1906, energetic reformer, this energetic reformer wants to modernize the Russian Empire, by allowing the peasants to acquire land, by organizing a better tax system and by granting more powers to the [[Duma]], the Russian parliament. He improved the rail system and increased the production of coal and iron. Stolypin does not understand the influence of this mystical <i>muzhik</i> on the imperial couple, while Rasputin reproaches the Prime Minister for his arrogance, characteristic of the class of large landowners from which he comes. | |

| − | + | During the Balkan affair in 1909 against Austria, Rasputin sided with the peace party alongside the Czarina and Anna Vyroubova against the rest of the Romanov clan. He believes that the Imperial Army, emerging weakened from the 1905 defeat against [[Japan]], is not ready to launch into a new conflict. He cannot stop the events, but when [[France]] and the [[United Kingdom]] intervene against Russia, he succeeds in convincing [[Nicolas II]] not to extend the conflict to all of Europe. | |

| − | + | Stolypin has Rasputin watched by the [[Okhrana]], the secret police. The Rasputin scandal broke out in 1910 during a [[press campaign]] orchestrated by deputies of the Duma and religious leaders, who denounced the debauched nature of Rasputin, indirectly targeting the Tsar. In 1911, Rasputin was removed from the Court and exiled to [[Kiev]], but, during a trance, he predicted the imminent death of the minister: "Death follows in his footsteps, death rides on his back". He then decides to set off on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, but returns to Court at the end of the summer. | |

| − | + | On September 14, 1911, while Stolypin has just authorized the peasants to leave the village commune, the <i>mir</i>, thus allowing them to access individual ownership of the land, and this reform is acclaimed throughout Russia, he is assassinated by the young anarchist [[Dmitri Bogrov]] in the presence of the imperial family, ministers, members of the Duma and Rasputin. This assassination marks the end of the reforms, while the international situation becomes unstable. | |

| − | + | On October 2 , 1912, Tsarevich Alexis, traveling in [Poland]], was the victim, following an accident, of a new internal bleeding, which could have lead to his death. Immediately informed, Rasputin goes into ecstasy before the icon of the Virgin of Kazan, and when he gets up, exhausted, he sends the message to the Palace: “Have no fear. God has seen your tears and heard your prayers, Mamka. Do not worry anymore. The Little One will not die. Don't allow the doctors to bother him too much”. Upon receipt of the telegram, Tsarevich Alexis' state of health stabilized and, the next day, began to improve: the swelling in his leg subsided, and the internal bleeding stopped. Doctors soon declare him out of danger, and even the most hostile to the "starets" must agree that there has been an almost miraculous event of distant healing. Savior, he returned triumphantly to Saint Petersburg.<ref>Massie, Robert K (2012) [1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (Modern Library ed.). ISBN 978-0-679-64561-0. page 192</ref> | |

| − | + | ==The Great War== | |

| + | The question of the dismemberment of the [[Ottoman Empire]] and the [[Balkans]] set the conditions for a general war. Rasputin and his peace allies seek, unsuccessfully, to slow down Russia's march towards war. The [[British intelligence service]] believes that it is in fact in contact with the banker [[Serge Rubinstein]] and his German networks<ref>Monique Lachère, Raspoutine , The Age of Man, 1990.</ref>. On June 29, 1914 Rasputin is stabbed by a beggar, [[Khionia Gousseva]], a former [[prostitute]], on leaving the church in his Siberian village. The investigation shows that the order came from the monk Iliodorus (real name Sergei Mikhailovich Troufanov), a fanatic of the nationalist movement of the [[Black Hundreds]]. Rasputin remains in [[Siberia]] until his recovery. Gousseva, declared insane, was placed in a [[psychiatric clinic]] and released in March [[1917]] by the provisional government, which saw her gesture as the act of a patriotic heroine.<ref>Tony Brenton, Historically Inevitable? Turning Points of the Russian Revolution, Profile Books, 2016, p. 127.</ref> | ||

| − | + | After this attack and his recovery, the importance of Rasputin becomes paramount and his influence is exercised in all areas: he intervenes in the careers of generals and metropolitans (priests) and even in the appointment of ministers. He begins to drink more alcohol and participate in even more evenings of debauchery and orgies. He is no longer the ascetic "starets" everyone respected. However, despite his debauched character and his less and less attractive appearance, his female conquests are more and more numerous in high society. | |

| − | + | On August 1st 1914, war is officially declared between Russia and [[Germany]]. Russian patriotism is exalted - mainly because of the first military successes - and Rasputin sees his favor decline. Quickly, however, the military situation deteriorated: a harsh winter, lack of armaments, supply problems, indecisive command, reckless risk-taking by supreme commander [[Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich]]. After the Great Retreat of 1915, Nicolas II, despite opposition from his ministers, decide to take command of the armies and moved to the front, leaving the regency to his wife and her private adviser Rasputin. | |

| − | + | The latter then gets more and more enemies, in particular among politicians, the military and the Orthodox clergy. The worst rumors are spread about him as the war turns into a disaster. In 1916, in the Duma, the Tsarina, who was of German origin, and Rasputin were openly accused of being on the enemy's side. | |

| − | + | ==Assassination of Rasputin== | |

| − | + | [[image:Oswald Rayner.jpg|thumb|British Secret Intelligence Service agent Oswald Rayner.]] | |

| − | + | [[image:Prince Felix Yusupov.jpg|thumb|Prince Felix Yusupov in 1914]] | |

| − | + | The historian [[Edvard Radzinsky]] was able to give the details of this assassination thanks to the archives of the Extraordinary Commission of 1917 and the secret file of the Russian police. | |

| − | + | The Yusupov family, worried about the influence of Rasputin on the imperial family and shocked by his scandalous reputation and debauchery, in which the names of women of the high nobility are mixed, opposes the "starets" more and more openly. Moreover, in the midst of the world war, it was rumored that he was spying for Germany. Several plots are brewing against him. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | A conspiracy leads to his assassination on the night of 16 to December 17, [[1916]] while he is the guest of Prince [[Felix Yusupov]], husband of the Grand Duchess Irina, niece of the Tsar. Among the main conspirators are the [[Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia]] -a cousin of Nicolas II and homosexual lover of Prince Yusupov - the far-right deputy Vladimir Pourishkevich, the officer Sukhotin, doctor Stanislas Lazovert as well as the British secret agent [[Oswald Rayner]]. | |

| − | == | + | ===Yusupov's story=== |

| − | + | Yusupov said he invited Rasputin to his home shortly after midnight and ushered him into the basement. Yusupov offered Rasputin tea and cakes which had been laced with [[cyanide]]. Rasputin initially refused the cakes but then began to eat them and, to Yusupov's surprise, appeared unaffected by the poison.<ref>Smith, Douglas (2016). Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. page 590.</ref> Rasputin then asked for some [[Madeira wine]] (which had also been poisoned) and drank three glasses, but still showed no sign of distress. At around 2:30 am, Yusupov excused himself to go upstairs, where his fellow conspirators were waiting. He took a revolver from Dmitry Pavlovich, then returned to the basement and told Rasputin that he'd "better look at the crucifix and say a prayer", referring to a crucifix in the room, then shot him once in the chest. The conspirators then drove to Rasputin's apartment, with Sukhotin wearing Rasputin's coat and hat in an attempt to make it look as though Rasputin had returned home that night. They then returned to the Moika Palace and Yusupov went back to the basement to ensure that Rasputin was dead. Suddenly, Rasputin leaped up and attacked Yusupov, who freed himself with some effort and fled upstairs. Rasputin followed and made it into the palace's courtyard before being shot by Purishkevich and collapsing into a snowbank. The conspirators then wrapped his body in cloth, drove it to the etrovsky Bridge, and dropped it into the Malaya Nevka River.<ref>Smith, Douglas (2016). Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. page 590-92.</ref> | |

| − | + | [[image:Dead Rasputin.jpg|thumb|The police photo album, stored in the archives of the Russian Political History Museum in St. Petersburg, was not made public until the early 2000s. These photos reveal Rasputin's face smashed and beaten, his body pierced by three bullets fired at close range.]] | |

| − | The | + | ===The autopsy conclusions=== |

| + | The corpse was found on December 19, 1916 in the early morning. Frozen and covered with a thick layer of ice, the corpse rose to the surface of the Neva river at the Petrovsky Bridge. | ||

| − | + | An autopsy is performed at the Military Academy by Professor Kossorotov on the very day of the discovery of the body. The autopsy report was not published and subsequently disappeared, which gave rise to numerous rumors<ref>Alain Roullier, Raspoutine est innocent, Nice, France Europe, 1998, page 514–516</ref>. The testimonies of those who consulted him agree on the existence of three entry holes, but their descriptions of the route differ from the testimonies of the four accomplices on the assassination, which are thus not reliable. One can however assume with some probability that the first two bullets fired from behind hit Rasputin while standing (the first entry through the thorax and having passed through the stomach and liver, the second entry through the lower back and having crossed a kidney), the third pulled from the front on the starets on the ground (entered by the front, it crossed the [[brain]])<ref>Yves Ternon, Raspoutine, une tragédie russe. 1906-1916, Éditions Complexe, 1991, p. 238-238.</ref>. The autopsy does not make it possible to conclude whether Rasputin died from poisoning, from concussions and severe beatings, or from gunshot bullets, but it is probable that the impact of the bullets were fatal. These uncertain conclusions have given rise to numerous rumors about the causes of Rasputin's death. | |

| − | + | A first version of the events indicates that the autopsy, made the same day of the discovery of the body at the Military Academy by Professor Kossorotov, revealed that Rasputin did not die of [[poison]], nor of [[bullets]], nor of concussions and beating, but from water in his lungs, which would prove he was still breathing when he was thrown into river. | |

| − | + | But a second version, which seems to be the official version, indicates that the "starets" was not poisoned, and died from a bullet fired point blank at the forehead. The autopsy shows that four bullets were fired by at least three different pistols - one of them more experienced than the other two, fires a bullet in the forehead using a Webley revolver which is the regulation weapon of the [[British Army]] and the personal weapon of [[Oswald Rayner]].<ref>http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fforum.alexanderpalace.org%2Findex.php%3Faction%3Dprintpage%3Btopic%3D1363.0</ref><ref>http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.dundee.ac.uk%2Fpressreleases%2Fprjan06%2Frasputin.html</ref> In reality, there was no presence of water in the lungs during the autopsy, and doctor Lazovert would later confess to Prince [[Felix Yusupov]] and to Dimitri Pavlovich that he never really supplied them with [[cyanide]], but a simple harmless product. Thus, the famous horror story of the night of 16 to December 17, 1916, giving Rasputin the appearance of a demon, is certainly pure invention. | |

| − | + | William Compton, the English driver of Oswald Rayner, confirms with his log book that he drove him six times to the Yusupov Palace for the preparations for the plot, and had often claimed that he was one of the shooters.<ref>Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin :The Untold Story, John Wiley & Sons, 24 September 2012, 320 pages, http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fbooks.google.com%2Fbooks%3Fid%3DljZhTg79ZocC%26pg%3DPA230</ref> | |

At the request of the Empress, Rasputin was buried on December 22, 1916 (January 4, 1917 in the Gregorian calendar) in a chapel under construction near the palace of Tsarskoye Selo. A commemorative monument was erected there in the 1990s. | At the request of the Empress, Rasputin was buried on December 22, 1916 (January 4, 1917 in the Gregorian calendar) in a chapel under construction near the palace of Tsarskoye Selo. A commemorative monument was erected there in the 1990s. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 81: | ||

==Legend== | ==Legend== | ||

| − | As early as 1917, the image of Rasputin was widely used by [[Bolshevik]] [[propaganda]] to symbolize the moral downfall of the old regime. It was taken up, distorted, amplified, by literature from 1917, then, from 1928, by cinema and television, which made | + | As early as 1917, the image of Rasputin was widely used by [[Bolshevik]] [[propaganda]] to symbolize the moral downfall of the old regime. It was taken up, distorted, amplified, by literature from 1917, then, from 1928, by cinema and television, which made his story an exploitation bordering on the fantastic and the erotic. |

| − | + | Journalists and politicians hostile to the Romanovs spread the rumor that Rasputin was the Tsarina's lover<ref name=Vladimir/>. The historian [[Edvard Radzinsky]], according to the secret Russian police file acquired at [[Sotheby's]], relativizes the erotomania and sexual debauchery of Rasputin: the defloration of nuns or the rape of ladies of the upper aristocracy were only rumors spread by people worried about his influence on the Court or hostile to the monarchical regime<ref>http://radzinski.ru/doc/books/rasputin</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | Journalists and politicians hostile to the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{SMWDocs}} | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | + | ||

{{PageCredit | {{PageCredit | ||

|site=Wikipedia | |site=Wikipedia | ||

Latest revision as of 11:12, 30 September 2021

(mystic, éminence grise) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 January 1869 Tobolsk, Siberia, Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 December 1916 (Age 47) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

Cause of death | assassination |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Interest of | Francis Cromie |

Russian mystic with great influence on the last Czar and Czarina of Russian. Murdered by British agents in 1916. | |

Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was a Russian mystic and healer. He was the confidant of Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Emperor Nicholas II, which allowed him to exercise a strong influence within the Russian imperial court. He was assassinated in 1916 by Russian aristocrats and agents of the British Secret Intelligence Service under the direction of agent Oswald Rayner, who shot him at point blank range. The British feared that Rasputin wanted to withdraw the Russian troops engaged in the First World War against Germany.

Originally from the Western Siberia, he presented himself as a strannik, a wandering mystical pilgrim, and claimed to be starets and prophet. While no ecclesiastical source attests to his membership of any religious order, he asserts his loyalty to the Russian Orthodox Church but is suspected of belonging to the sect of the Khlysts. The most generally accepted hypothesis is that he is above all was an adventurer, presenting himself as an itinerant pilgrim, and endowed with a great power of seduction, in no small part due to his intense gaze.

Already renowned as a healer, in 1905 he was invited for the first time by the imperial couple to the bedside of their son, Alexis, heir to the throne suffering from hemophilia. Rasputin gained steadily more influence, especially during World War 1. The Czarina and his family considered him a healer, a mystic, even a prophet. His enemies described him as a debauched charlatan, driven by an inordinate sexual appetite and even as a spy. He thus participates in the discrediting the imperial family and constitutes one of the elements of the fall of the Romanovs. He was assassinated following a plot fomented by members of the aristocracy in collaboration with the British Secret Intelligence Service.

Some gray areas remain about his life and influence, his biography being mostly based on biased testimonies, in part fueled by anti-monarchist propaganda, rumors and legends. After his death, his myth inspired many writers and artists. Long demonized, he subsequently enjoyed a less unfavorable opinion in Russia than during his lifetime.

Contents

With the imperial family

The Czarina, long worried about not giving a male heir to the crown, had become accustomed to attracting around her many mystics and healers. Through the Grand Duchess Militza and her sister, Grand Duchess Anastasia , the "starets" is presented to the imperial family on November 1, 1905. Tsarevich Alexis suffering from hemophilia, Rasputin asked to be taken to the bedside of the young patient who was bedridden after a fall, which caused a huge hematoma in the knee. He lays his hands on him, tells him several Siberian tales and thus manages, it seems, to stem the crisis and relieve him after a few days. According to some, this could be explained by the simple fact that the medicine of the time ignored the properties of the aspirin which was given to the young patient. This drug is an anticoagulant, an aggravating factor in hemophilia. The simple fact of sweeping the table and throwing away the "remedies" given to the patient - including aspirin - could only have improved his condition.[1]

The parents are seduced by the healing gifts of this humble "muzhik" who also seems to have that of prophecy. Alexandra convinced herself that Rasputin was a messenger from God, that he represented the union of the Tsar, the Church and the people and that he had the capacity to help her son with his healing gifts and his prayer.

His reputation allowed Rasputin to make himself indispensable; he very quickly gathers a considerable influence over the imperial couple. He is invited to many social gatherings, and got to know many wealthy women. Rasputin fascinates: his piercing gaze is difficult to resist for his admirers, many give in to his hypnotic charm and take him for a lover and/or a healer.

Although not enriching himself, he continued to lead a dissolute life of drinking and debauchery, retaining his greasy hair and tangled beard[2]. He throws parties in his apartment, where sex dominates - up to ten sexual relations a day[3] - and alcohol. He preaches his doctrine of redemption through sin among the ladies, eager to go to bed with him to practice his teaching, which they see as an honor.

After the revolution of 1905, Rasputin came up against the President of the Council Piotr Stolypin. Appointed in mJuly 1906, energetic reformer, this energetic reformer wants to modernize the Russian Empire, by allowing the peasants to acquire land, by organizing a better tax system and by granting more powers to the Duma, the Russian parliament. He improved the rail system and increased the production of coal and iron. Stolypin does not understand the influence of this mystical muzhik on the imperial couple, while Rasputin reproaches the Prime Minister for his arrogance, characteristic of the class of large landowners from which he comes.

During the Balkan affair in 1909 against Austria, Rasputin sided with the peace party alongside the Czarina and Anna Vyroubova against the rest of the Romanov clan. He believes that the Imperial Army, emerging weakened from the 1905 defeat against Japan, is not ready to launch into a new conflict. He cannot stop the events, but when France and the United Kingdom intervene against Russia, he succeeds in convincing Nicolas II not to extend the conflict to all of Europe.

Stolypin has Rasputin watched by the Okhrana, the secret police. The Rasputin scandal broke out in 1910 during a press campaign orchestrated by deputies of the Duma and religious leaders, who denounced the debauched nature of Rasputin, indirectly targeting the Tsar. In 1911, Rasputin was removed from the Court and exiled to Kiev, but, during a trance, he predicted the imminent death of the minister: "Death follows in his footsteps, death rides on his back". He then decides to set off on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, but returns to Court at the end of the summer.

On September 14, 1911, while Stolypin has just authorized the peasants to leave the village commune, the mir, thus allowing them to access individual ownership of the land, and this reform is acclaimed throughout Russia, he is assassinated by the young anarchist Dmitri Bogrov in the presence of the imperial family, ministers, members of the Duma and Rasputin. This assassination marks the end of the reforms, while the international situation becomes unstable.

On October 2 , 1912, Tsarevich Alexis, traveling in [Poland]], was the victim, following an accident, of a new internal bleeding, which could have lead to his death. Immediately informed, Rasputin goes into ecstasy before the icon of the Virgin of Kazan, and when he gets up, exhausted, he sends the message to the Palace: “Have no fear. God has seen your tears and heard your prayers, Mamka. Do not worry anymore. The Little One will not die. Don't allow the doctors to bother him too much”. Upon receipt of the telegram, Tsarevich Alexis' state of health stabilized and, the next day, began to improve: the swelling in his leg subsided, and the internal bleeding stopped. Doctors soon declare him out of danger, and even the most hostile to the "starets" must agree that there has been an almost miraculous event of distant healing. Savior, he returned triumphantly to Saint Petersburg.[4]

The Great War

The question of the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and the Balkans set the conditions for a general war. Rasputin and his peace allies seek, unsuccessfully, to slow down Russia's march towards war. The British intelligence service believes that it is in fact in contact with the banker Serge Rubinstein and his German networks[5]. On June 29, 1914 Rasputin is stabbed by a beggar, Khionia Gousseva, a former prostitute, on leaving the church in his Siberian village. The investigation shows that the order came from the monk Iliodorus (real name Sergei Mikhailovich Troufanov), a fanatic of the nationalist movement of the Black Hundreds. Rasputin remains in Siberia until his recovery. Gousseva, declared insane, was placed in a psychiatric clinic and released in March 1917 by the provisional government, which saw her gesture as the act of a patriotic heroine.[6]

After this attack and his recovery, the importance of Rasputin becomes paramount and his influence is exercised in all areas: he intervenes in the careers of generals and metropolitans (priests) and even in the appointment of ministers. He begins to drink more alcohol and participate in even more evenings of debauchery and orgies. He is no longer the ascetic "starets" everyone respected. However, despite his debauched character and his less and less attractive appearance, his female conquests are more and more numerous in high society.

On August 1st 1914, war is officially declared between Russia and Germany. Russian patriotism is exalted - mainly because of the first military successes - and Rasputin sees his favor decline. Quickly, however, the military situation deteriorated: a harsh winter, lack of armaments, supply problems, indecisive command, reckless risk-taking by supreme commander Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich. After the Great Retreat of 1915, Nicolas II, despite opposition from his ministers, decide to take command of the armies and moved to the front, leaving the regency to his wife and her private adviser Rasputin.

The latter then gets more and more enemies, in particular among politicians, the military and the Orthodox clergy. The worst rumors are spread about him as the war turns into a disaster. In 1916, in the Duma, the Tsarina, who was of German origin, and Rasputin were openly accused of being on the enemy's side.

Assassination of Rasputin

The historian Edvard Radzinsky was able to give the details of this assassination thanks to the archives of the Extraordinary Commission of 1917 and the secret file of the Russian police. The Yusupov family, worried about the influence of Rasputin on the imperial family and shocked by his scandalous reputation and debauchery, in which the names of women of the high nobility are mixed, opposes the "starets" more and more openly. Moreover, in the midst of the world war, it was rumored that he was spying for Germany. Several plots are brewing against him.

A conspiracy leads to his assassination on the night of 16 to December 17, 1916 while he is the guest of Prince Felix Yusupov, husband of the Grand Duchess Irina, niece of the Tsar. Among the main conspirators are the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia -a cousin of Nicolas II and homosexual lover of Prince Yusupov - the far-right deputy Vladimir Pourishkevich, the officer Sukhotin, doctor Stanislas Lazovert as well as the British secret agent Oswald Rayner.

Yusupov's story

Yusupov said he invited Rasputin to his home shortly after midnight and ushered him into the basement. Yusupov offered Rasputin tea and cakes which had been laced with cyanide. Rasputin initially refused the cakes but then began to eat them and, to Yusupov's surprise, appeared unaffected by the poison.[7] Rasputin then asked for some Madeira wine (which had also been poisoned) and drank three glasses, but still showed no sign of distress. At around 2:30 am, Yusupov excused himself to go upstairs, where his fellow conspirators were waiting. He took a revolver from Dmitry Pavlovich, then returned to the basement and told Rasputin that he'd "better look at the crucifix and say a prayer", referring to a crucifix in the room, then shot him once in the chest. The conspirators then drove to Rasputin's apartment, with Sukhotin wearing Rasputin's coat and hat in an attempt to make it look as though Rasputin had returned home that night. They then returned to the Moika Palace and Yusupov went back to the basement to ensure that Rasputin was dead. Suddenly, Rasputin leaped up and attacked Yusupov, who freed himself with some effort and fled upstairs. Rasputin followed and made it into the palace's courtyard before being shot by Purishkevich and collapsing into a snowbank. The conspirators then wrapped his body in cloth, drove it to the etrovsky Bridge, and dropped it into the Malaya Nevka River.[8]

The autopsy conclusions

The corpse was found on December 19, 1916 in the early morning. Frozen and covered with a thick layer of ice, the corpse rose to the surface of the Neva river at the Petrovsky Bridge.

An autopsy is performed at the Military Academy by Professor Kossorotov on the very day of the discovery of the body. The autopsy report was not published and subsequently disappeared, which gave rise to numerous rumors[9]. The testimonies of those who consulted him agree on the existence of three entry holes, but their descriptions of the route differ from the testimonies of the four accomplices on the assassination, which are thus not reliable. One can however assume with some probability that the first two bullets fired from behind hit Rasputin while standing (the first entry through the thorax and having passed through the stomach and liver, the second entry through the lower back and having crossed a kidney), the third pulled from the front on the starets on the ground (entered by the front, it crossed the brain)[10]. The autopsy does not make it possible to conclude whether Rasputin died from poisoning, from concussions and severe beatings, or from gunshot bullets, but it is probable that the impact of the bullets were fatal. These uncertain conclusions have given rise to numerous rumors about the causes of Rasputin's death.

A first version of the events indicates that the autopsy, made the same day of the discovery of the body at the Military Academy by Professor Kossorotov, revealed that Rasputin did not die of poison, nor of bullets, nor of concussions and beating, but from water in his lungs, which would prove he was still breathing when he was thrown into river.

But a second version, which seems to be the official version, indicates that the "starets" was not poisoned, and died from a bullet fired point blank at the forehead. The autopsy shows that four bullets were fired by at least three different pistols - one of them more experienced than the other two, fires a bullet in the forehead using a Webley revolver which is the regulation weapon of the British Army and the personal weapon of Oswald Rayner.[11][12] In reality, there was no presence of water in the lungs during the autopsy, and doctor Lazovert would later confess to Prince Felix Yusupov and to Dimitri Pavlovich that he never really supplied them with cyanide, but a simple harmless product. Thus, the famous horror story of the night of 16 to December 17, 1916, giving Rasputin the appearance of a demon, is certainly pure invention.

William Compton, the English driver of Oswald Rayner, confirms with his log book that he drove him six times to the Yusupov Palace for the preparations for the plot, and had often claimed that he was one of the shooters.[13]

At the request of the Empress, Rasputin was buried on December 22, 1916 (January 4, 1917 in the Gregorian calendar) in a chapel under construction near the palace of Tsarskoye Selo. A commemorative monument was erected there in the 1990s.

In the evening of March 22, 1917, on the orders of the new Provisional Revolutionary Government, Rasputin's body is exhumed. To make it disappear, the body and its coffin are brought back to Saint Petersburg and cremated in a boiler at the Polytechnic Institute, then its ashes are scattered in the surrounding forests. But, according to legend, only the coffin burned, Rasputin's body remaining intact in the flames.

Legend

As early as 1917, the image of Rasputin was widely used by Bolshevik propaganda to symbolize the moral downfall of the old regime. It was taken up, distorted, amplified, by literature from 1917, then, from 1928, by cinema and television, which made his story an exploitation bordering on the fantastic and the erotic.

Journalists and politicians hostile to the Romanovs spread the rumor that Rasputin was the Tsarina's lover[3]. The historian Edvard Radzinsky, according to the secret Russian police file acquired at Sotheby's, relativizes the erotomania and sexual debauchery of Rasputin: the defloration of nuns or the rape of ladies of the upper aristocracy were only rumors spread by people worried about his influence on the Court or hostile to the monarchical regime[14].

References

- ↑ Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2012). Rasputin: The Untold Story. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-23985-8.

- ↑ Revière, Perez et Grossmann, « Les Secrets de la mort de Raspoutine », Io - Martange, série « L'Ombre d'un doute, 13 », 28e min 50 s.

- ↑ a b Vladimir Fédorovski, Le Roman de Raspoutine, Éditions du Rocher, 2011, 220 p.

- ↑ Massie, Robert K (2012) [1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (Modern Library ed.). ISBN 978-0-679-64561-0. page 192

- ↑ Monique Lachère, Raspoutine , The Age of Man, 1990.

- ↑ Tony Brenton, Historically Inevitable? Turning Points of the Russian Revolution, Profile Books, 2016, p. 127.

- ↑ Smith, Douglas (2016). Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. page 590.

- ↑ Smith, Douglas (2016). Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. page 590-92.

- ↑ Alain Roullier, Raspoutine est innocent, Nice, France Europe, 1998, page 514–516

- ↑ Yves Ternon, Raspoutine, une tragédie russe. 1906-1916, Éditions Complexe, 1991, p. 238-238.

- ↑ http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fforum.alexanderpalace.org%2Findex.php%3Faction%3Dprintpage%3Btopic%3D1363.0

- ↑ http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.dundee.ac.uk%2Fpressreleases%2Fprjan06%2Frasputin.html

- ↑ Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin :The Untold Story, John Wiley & Sons, 24 September 2012, 320 pages, http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fbooks.google.com%2Fbooks%3Fid%3DljZhTg79ZocC%26pg%3DPA230

- ↑ http://radzinski.ru/doc/books/rasputin

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here