Document:Upskilling to Upscale: Unleashing the Capacity of Civil Society to Counter Disinformation

| A central II-document. The master plan for a huge network of British-directed NGOs in Europe. ‘Disinformation’ refers to everything not fitting the Western government narrative... |

Subjects: influence networks, Bellingcat, Correctiv, Latvian Elves, Atlantic Council

Example of: Integrity Initiative/Leak/7

Source: Anonymous (June2018_RestrictedAccess_June2018 (1) Link)

The index has been edited for clarity. Not all page numbers are included. Page numbers on top of page. Tables have been changed to lists.

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Upskilling to Upscale: Unleashing the Capacity of Civil Society to Counter Disinformation

Contents

- 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- 2 UNDERSTANDING DISINFORMATION

- 2.1 DEFINITIONS

- 2.2 STRATEGY AND TACTICS

- 2.2.1 INTENT: DESTROY FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS’ REPUTATIONS

- 2.2.2 INTENT: WEAKEN INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCES

- 2.2.3 INTENT: DISTORT NATIONAL POLITICAL DISCOURSE TO PROMOTE RUSSIAN INTERESTS / BOOST INDIVIDUALS AND ORGANISATIONS WHO SERVE RUSSIAN PURPOSES

- 2.2.4 INTENT: UNDERMINE TRUST IN PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS

- 2.2.5 INTENT: INFLUENCE ELECTORAL AND POLITICAL OUTCOMES

- 2.2.6 INTENT:INCREASE POLARIZATION

- 2.3 REGIONAL ANALYSIS

- 3 RESPONDING TO DISINFORMATION

- 4 STRATEGIC APPROACH

- 5 RECOMMENDATIONS

- 6 Annex A NEEDS ASSESSMENT FINDINGS

- 7 Annex B RISK MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK

- 8 ANNEX C: INFORMATION SHARING FRAMEWORK

- 9 ANNEX D PROPOSED NETWORK MEMBERS

- 10 ANNEX E: REGIONAL REPORTS

- 11 Original Index

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Europe is under an increasing threat from Kremlin-backed disinformation. The Kremlin aims to contaminate the information ecosystem in order to destroy foreign governments’ reputations, weaken international alliances, increase polarisation, undermine trust in government and other major institutions, influence political and in particular electoral outcomes and, ultimately, enhance Russian global influence.

These disinformation efforts are proving successful across Europe due to the fact they exploit existing fissures and debates in society, require low barriers to entry, are able to circumnavigate a weak regulatory environment, and exploit low levels of public awareness and a lack of critical media consumption. The rise of ‘deep fake’ technology and other tools for image and video manipulation is an additional urgent concern.

There is a pressing need to counter disinformation with high quality, credible content that exposes and counters false narratives in real time and builds resilience over the long term among populations vulnerable to Kremlin influence. The complexity of Kremlin-backed disinformation and its regional nuances requires a response that is regionally based and adaptive to local scenarios, but also draws on a broader understanding of the Kremlin’s strategic goals.

Due to the scale and gravity of the threat across Europe, there are an increasing number of organisations with a high commitment to understanding and countering Kremlin-backed disinformation, often doing so in the face of strong opposition and with little remuneration or support for their work. Civil society organisations are uniquely placed to counter Kremlin disinformation as they have the commitment, mission and potentially the credibility to not only counter disinformation but also build long-term resilience to it through positive messaging, improving regulation and building awareness and critical thinking amongst the public.

This scoping research included an in-depth analysis of existing organisations around Europe countering disinformation using a variety of tactics including public awareness campaigns, the development of tech tools, the development of research products, and open source research into the networks and sources of disinformation. These organisations include media outlets, think tanks, and grassroots implementors running projects that include promoting media literacy and community cohesion. It found that despite significant achievements in the fields of fact-checking and debunking, research, public facing campaigns, network analysis, investigative journalism and media literacy, there are core weaknesses that undermine the ability of organisations to effectively counter disinformation.

The majority of these organisations are operating completely independently in a disparate fashion without sharing best practice. Their outputs have varying degrees of quality and effectiveness, and are not informed by the latest data and research, and they have limited operational capacity to do this work at the pace and scale required.

An opportunity exists to upskill civil society organisations around Europe, enhancing their existing activities and unleashing their potential to effectively counter disinformation. If supported to deliver their activities in a professional manner that holds them above reproach, while gaining access to a variety of support functions, best practice and high-quality training these organisations have the potential to be the next generation of activists in the fight against Kremlin disinformation.

The EXPOSE Network sets out to identify civil society organisations operating across Europe countering disinformation using a variety of tactics, upskill these organisations in research and communications and through the provision operational support, grants and training, and coordinate their activities to ensure effectiveness and measure impact through research and evaluation.

Four key barriers to countering disinformation effectively can be identified across the region as a whole. Organisations lack:

• The expertise, guidance and tools to deliver high-quality open source research

• The ability and support to conceptualise and deliver public facing campaigns and communications products that challenge public perceptions about disinformation

• Access to grant funding, relationships with donors, and the ability to write funding proposals, severely limiting their sustainability, as well as qualified staff

• The security frameworks and legal training to run streamlined and low-risk operations

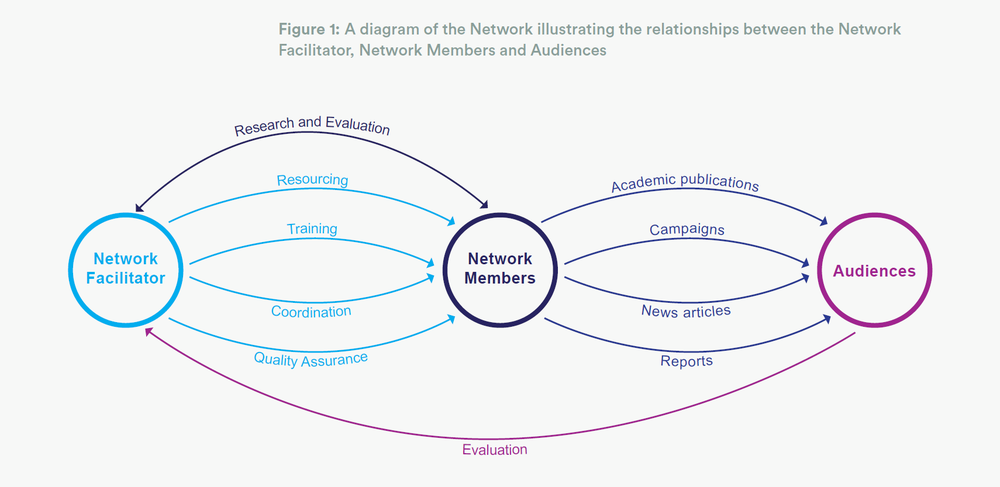

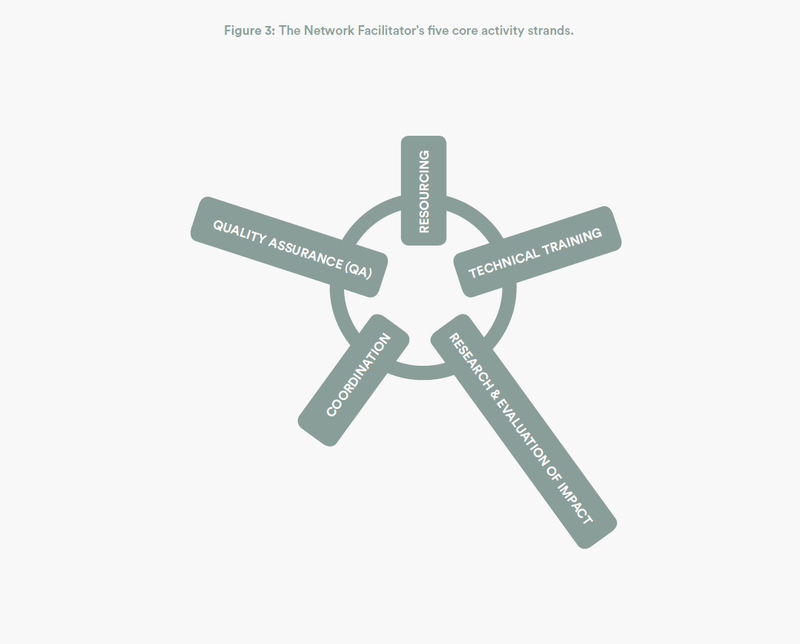

The operating model proposed will address these key barriers highlighted through the provision of five activity strands. These will run in parallel throughout the three-year implementation period. Resourcing will include a grant funding mechanism, and will ensure that organisations have access to legal, security and other operations support to enable them to deliver their work within a safe and well-resourced environment. Training will include a variety of learning packages, from online courses to embedded learning with dedicated specialists and regional events focused on topics including cyber security and enhancing communications outputs. Research and evaluation of impact will involve both a study of disinformation as it emerges online and the evaluation of the activities of network members to better understand their impact on the target audiences. Coordination of activities and network members will foster synergies between research interests, promote regional cooperation, and facilitate networking, as well as drawing together activities and promoting specific approaches if necessary. The Quality Assurance (QA) strand will ensure that wherever possible outputs from Network members are created within rigorous journalistic, fact-checking and legal frameworks and will drive to increase quality in both research and communications.

In delivering activities across the five strands of resourcing, training, QA, coordination of activities, and research and evaluation of impact, the Network Facilitator will achieve a joined-up approach that matches technical training with the provision of funds and tools, ensures activities are not only delivered to a high standard but coordinated in order to achieve maximum impact, and provides a crucial layer of impact measurement to all the work undertaken by Network members.

This will in turn increase the quality and quantity of counter-disinformation content, increase the sustainability and professionalism of organisations countering disinformation, create an ecosystem of credible voices which can continue to grow and counter the disinformation ecosystem exploited by the Kremlin, build awareness amongst key audiences, and help to establish best practice on countering disinformation. These outputs will contribute to the undermining of the credibility of the Kremlin, their narratives and online networks, build resilience to disinformation in vulnerable audiences across Europe, and reduce the number of unwitting multipliers of disinformation.

The upskilling of civil society organisations across Europe represents a unique opportunity for the FCO to adopt a joined-up approach, ensuring information sharing between the private sector, civil society and Government while enabling civil society organisations to counter disinformation in a way that matches the challenge in their local contexts.

UNDERSTANDING DISINFORMATION

DEFINITIONS

In this report, ‘disinformation’ refers to Kremlin influence operations within the communications environment, delivered through overt and covert promotion of intentionally false, distorting or distracting narratives. Kremlin influence operations form part of a much broader foreign policy toolkit, which includes the use of official and illicit money, corruption, economic pressure, assassinations, online hacking, political party funding, support for extremist movements and the use of the Orthodox Church and state-controlled NGOs in foreign policy. This project scoping has taken a broad approach to disinformation both in the way it can be understood and in approaches to countering it.

STRATEGY AND TACTICS

The Kremlin aims to contaminate the information ecosystem in order to destroy foreign governments’ reputations, weaken international alliances, increase polarisation, undermine trust in government and other major institutions, influence political and in particular electoral outcomes and, ultimately, enhance Russian global influence. The Kremlin’s objectives and tactics are summarised in the following table:

INTENT: DESTROY FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS’ REPUTATIONS

STRATEGY:

Inventing/promoting smear campaigns and alternative narratives through Kremlin-attributed media and Kremlin public diplomacy.

Promoting these narratives by non-attributed and attributed Kremlin activity.

Using troll/bot networks to swamp and distort discussion.

EXAMPLE:

Smear campaign against the White Helmets, a group trusted by the UK government, especially their evidence of the use of chemical weapons by Russia and its allies in Syria.

Corroding confidence in the UK’s political system through bringing into question the integrity of the Scottish independence referendum.

INTENT: WEAKEN INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCES

STRATEGY:

Creating campaigns inventing or highlighting decadence, corruption, hypocrisies or decay of institutions.

Promoting these narratives through both nonattributed and attributed Kremlin media / social media.

EXAMPLE:

Creating multiple false narratives to reject the UK government’s analysis of the poisoning of the Skripals in Salisbury or muddying the waters around the shooting down of the MH17 airliner by Russian-controlled forces in Ukraine.

INTENT: DISTORT NATIONAL POLITICAL DISCOURSE TO PROMOTE RUSSIAN INTERESTS / BOOST INDIVIDUALS AND ORGANISATIONS WHO SERVE RUSSIAN PURPOSES

STRATEGY:

Promoting pro-Kremlin topics on RT/Sputnik (and via RT/Sputnik social media channels).

Inserting Kremlin narratives into the mainstream media through the use of public diplomacy.

Using troll/bot networks to swamp and distort discussion.

Deployment of campaigns through troll/bot networks to divert energy and attention from discussing Kremlin activity.

Championing of third-party advocates to simulate credibility to Kremlin narratives.

EXAMPLE:

Disinformation campaign aimed at Russian minorities in Eastern Europe, and Slavic and Christian Orthodox ‘brethren’ in South Eastern Europe with historical ties to Russia, in order to galvanise domestic pressure for stronger links to Russia.

In Serbia, Kremlin disinformation has instilled the false idea that the Kremlin offers more investment into the Balkans than the EU.

INTENT: UNDERMINE TRUST IN PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS

STRATEGY:

Amplifying anti-government voices.

Undermining key institutions such as public service broadcasters.

Promoting narratives about the economic or military unviability of a government.

Increasing divisions between minority communities and their government.

EXAMPLE:

Narratives that Ukraine is economically a failed state and can only survive if it is propped up by the EU or Russia.

Smear campaign against the BBC.

Narratives in Baltics that Russian speakers are persecuted by the government.

INTENT: INFLUENCE ELECTORAL AND POLITICAL OUTCOMES

STRATEGY:

Promoting candidates or discrediting others in order to achieve specific outcomes.

EXAMPLE:

Disinformation campaigns interfering in US elections, Italian elections, Catalan independence referendum.

INTENT:INCREASE POLARIZATION

STRATEGY:

Amplifying existing far-left and far-right narratives on social media through providing fodder for consumption and opinion entrenchment.

Using troll/bot networks to swamp and distort discussion, making the narratives ‘unavoidable’ on social media.

Manipulating far right groups, far left groups, anti-Zionists, conspiracy theorists, Kremlin sympathisers, and critics of the mainstream media, who opportunistically amplify content produced by fringe networks moving them from ‘Kremlin-narrative observers’ to ‘Kremlin-narrative contemplators/sympathisers/amplifiers’.

Fringe networks sharing this content used key mainstream hashtags when amplifying content, resulting in fringe network activity bleeding into the mainstream.

EXAMPLE:

Stoking ethnic and religious hatred following the terror attacks in the UK and France in early 2017.

Creating alarmist stories about mass migration into Germany, and across the EU generally.

Inflaming the situation around Catalan separatists during the ‘independence’ vote.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 5

These disinformation efforts are proving successful across Europe due to the fact they:

• Exploit existing fissures and debates in society. Disinformation mobilises existing communities of interest both online and offline, including those who are already alienated from the mainstream for a variety of reasons, including the legacy of the disintegration of the Soviet Union and existing ethno-political tensions.

• Require low barriers to entry. The technical tools necessary to create and disseminate disinformation are easily accessible and require low levels of ability and cost to produce at high volume. The rise of tools for image and video manipulation, including ‘deep fakes’, is an additional factor that will increase the Kremlin’s ability to create credible disinformation.

• Circumnavigate a weak regulatory environment. The Kremlin’s tactics are playing out in a context where the introduction of digital media has led to new forms of influence campaigns waged by all political and commercial actors, around which there exists little or no regulation or norms. There are few existing frameworks and little public awareness around how the public’s online data can be used by technology companies, or around what constitutes legitimate political advertising online or what forms of digital amplification (such as Search Engine Optimisation or the use of automated accounts) are legitimate.

• Exploit low levels of public awareness and a lack of critical media consumption.

There is a pressing need to counter disinformation with high quality, credible content that exposes and counters false narratives in real time and builds resilience over the long term among populations vulnerable to Kremlin influence.

REGIONAL ANALYSIS

The scope of this research was Europe, with a focus on the areas prioritised by the FCO.

The strategy and tactics implemented by the Kremlin in each territory are varied and shifting, and it is therefore important to take a local and contextually specific approach to both understanding and countering disinformation.

BALKANS

These countries face a ‘dual threat’ from Kremlin disinformation and from local media which echoes Kremlin narratives, and which are in some cases supported by the Kremlin. Narratives aim to pull countries away from the EU and NATO, to stir ultra-nationalism, and to destabilise peace efforts. In neighbouring countries, disinformation is partnered with attempted coups, the alleged training of paramilitaries and the subversion of election results.

For example, in Bulgaria there are a large number of narratives pushed by the Kremlin, including the moral and political decline of Europe, and conspiracy theories about the refugee crisis being a United States/CIA plot. The European Union is routinely subject to scrutiny. At times, stories portray Brussels as a malevolent prime mover, while at others, the EU is depicted as being a puppet of foreign governments and corporate interests, with George Soros featuring prominently.

BALTICS

In the Baltic states, disinformation efforts primarily target Russian-speaking populations, who are more naturally drawn toward the Kremlin’s sphere of influence. Russian state TV is popular and supported by online and offline media in titular languages, including the recent launch of Sputnik in Lithuanian. Disinformation aims to polarise countries along ethnic and linguistic lines, furthering a sense of grievance among Russian speakers. Narratives are also aimed at discrediting the EU and NATO, with NATO soldiers a particular target for disinformation.

CENTRAL EUROPE

Kremlin disinformation plays into local political dynamics, preying on far-left and far-right narratives, particularly anti-immigration and anti-EU themes. These dovetail with narratives pushed by some heads of government, who in turn support Kremlin interests. In addition, internet news resources with opaque ownership push Kremlin narratives in a structured and strategic manner.

An example of this can be seen in the Czech Republic where two cross-cutting issues exploited by the Kremlin are negative attitudes towards migration, especially from Muslim countries, and negative sentiment towards the EU; these are also exploited by far right groups. A similar pattern was also observed in Hungary, where disinformation spreads far-right narratives about migration, liberalism and the EU.

CAUCASUS

In the Caucasus, Kremlin narratives are imported via the church, ethno-nationalist and anti- LGBT NGOs. Their aim is to push Georgia away from pursuing policies which align it to the EU and to weaken Georgian cooperation with NATO.

EASTERN EUROPE

In Ukraine, Kremlin legacy media and digital media still makes inroads, despite bans on Russian TV and social media companies. Its aim is to stir unrest and alienate Ukraine from its Western allies by, for example, inflaming Poland-Ukraine tensions.

Belarus and Moldova operate in a ‘dual threat’ environment. The Moldovan government pays lip service to the West by, for example, enacting an anti-propaganda law that purportedly banned propagandist outlets but simultaneously placated Russia by excluding a number of Russian TV stations from the ban.

In Belarus, media freedom is severely restricted. In Moldova, disinformation narratives cut across several key issues. The notion that if Moldova joins the EU then churches will be closed and Christian burials will be banned because European countries are not religious has gained prominence. Like in the Balkans, the prospect of being forced to support LGBT rights by Europe is used to turn people against the European project.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 7

SOUTHERN EUROPE

The Kremlin uses Spanish-language disinformation to reach audiences in Southern Europe and further afield in Latin America and the United States. Disinformation spreads through Kremlin Spanish language broadcasters and across social media networks, where Kremlin accounts work in concert with Venezuelan ones. Narratives have included support for Catalan independence and support for Russian military interventions in Ukraine and Syria.

WESTERN EUROPE

Disinformation campaigns in Western Europe support far right and far left movements, fuelling polarisation. In the UK and elsewhere, disinformation is also spread to support Russian foreign policy objectives, including assassinations and invasions, to interfere in elections, and to attack politicians and influential individuals seen as unfavourable to the Kremlin. It is also deployed in the wake of terror attacks to promote hatred and increase social polarisation. The complexity of Kremlin-backed disinformation and its regional nuances requires a response that is regionally based and adaptive to local scenarios, but also draws on a broader understanding of the Kremlin’s strategic goals.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 8

Stakeholders from across society, including governments, the private sector and civil society organisations, are all engaged in responding to disinformation, with varying degrees of success. This scoping research analysed a wide range of tactics in order to gain a full picture of the impact, strengths and weaknesses of different approaches. Through extensive consultation with experts in the field and a literature review, we divided the range of approaches to tackling disinformation into six key strands, which are discussed in depth below.

RESPONDING TO DISINFORMATION

TYPES OF RESPONSE

FACT-CHECKING AND DEBUNKING

This activity has a long tradition. During the Cold War, the US Government’s inter-agency Active Measures Working Group tracked Soviet disinformation across the world, produced regular reports for Congress and communicated results to the press. The Working Group helped raise awareness of Soviet techniques among policy and media actors, which contributed to a broader narrative which undermined Soviet credibility.

The speed of production and distribution of content makes this a challenging endeavour in the present day. The media environment is no longer mediated by a handful of regulated outlets, and many content providers have no professional, commercial or regulatory interest in engaging with mythbusting. Furthermore, the fracturing of audiences means that vulnerable groups can be harder to reach, with an increasing body of research indicating that ‘debunking’ can in fact lead to unintended or even opposite results.1

Footnote 1 See Nyhan, B. and Reifler, J. (2010) ‘When Corrections Fail: The persistence of political misperceptions’, Political Behaviour 32: 303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2; and Schmidt, A.K., Zollo, F., Scala, A., Betsch, C., and Quattrociocchi, W., (2018, May), ‘Polarization of the vaccination debate on Facebook’ in Vaccine https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29773322

Fact-checking institutions have grown rapidly across Europe, with the best ones signing up to the Poynter code of conduct and standards. Some of the most professional organisations are in Western Europe and areas with a strong Western donor presence, such as the Balkans. Central Europe is sorely lacking in this specialisation. Most fact-checking organisations however do not necessarily focus on the disinformation aspect, instead sticking to fact-checking politicians and mainstream media statements. Those organisations that do focus on debunking Kremlin fakes do not always follow the most rigorous standards.

The problems facing the sector can be seen in the complaints against the ‘EU versus Disinformation’ unit at the European External Action Service, which focus on questions of terminology and methodology. Though largely unfair, the complaints show how the lack of common agreement between researchers, academics and media on such questions can undermine the whole sector.

Despite these challenges, there have been notable incidents of fact-checking shifting public opinion and resulting in the source of a piece of disinformation backing down. There is huge potential here for civil society organisations to tread the path established by independent social media users and media outlets. Fact checking can have a key role in stopping journalists and other trusted social media amplifiers and influencers from sharing disinformation content, and also from undermining the credibility of the sources of that content via drawing attention to the sources. Satire has been particularly effective in this regard, as the following case study shows:

CHANNEL ONE EURASIA FORCED TO BACK DOWN In 2016, in the midst of widespread protests against the Kazakhstani government’s proposed land reform legislation, Channel One Eurasia (the Channel One affiliate in Kazakhstan) broadcast a video that it claimed proved that foreign agents were funding the protest. The badly-shot, clearly fake video featured anonymous provocateurs stuffing money into back pockets of ‘protesters’. Social media users responded by producing dozens of parody clips lampooning the fake video; many of these went viral under hashtags mocking Channel One. As a result of the social media uproar, several staff members at Channel One were fired, and a Russian producer returned to Moscow.

DELFI: DEMASKUOK PROJECT Delfi, the largest fact checker in Lithuania has launched a pioneering project called ‘Demaskuok’ (‘uncover’). Readers of the website are able to submit stories that they think might be inaccurate for Delfi journalists to fact-check. This arose from an awareness on the part of the organization that “false news and deliberate misinformation have become more common in global social networks.” They hope that their project will stop the “spread of panic,” and other real-world losses associated with disinformation.

RESEARCH

Research conducted in this space needs to include analysis of the type of content being spread and the narratives it pushes, analysis of the tools and methods through which it is disseminated, and the ways in which it is consumed by audiences. Think tanks and academic institutions regularly conduct deep and comprehensive analysis of Kremlin narratives. Such research can raise awareness of the scope and strategy of Kremlin activities among policy makers and media elites. It is slow, however, and makes no effort to keep pace with an ever-evolving landscape. It also rarely includes monitoring of narratives in real-time using social media monitoring tools.

Organisations in Central Europe and the Baltics excel in this area, as do the more established Western European think tanks. Such in-depth research tends to be targeted very narrowly at the policy-making and expert community and does not provide a feedback loop into predicting and countering Kremlin campaigns. Other regions, including Southern Europe, are sorely lacking in a deep understanding of the Kremlin’s strategies, which could be both a cause and effect of their governments’ reluctance to confront this issue. A concerted, transnational research and public awareness effort is necessary to ensure it is at the top of the political agenda in all the regions affected by Kremlin disinformation.

Monitoring of Kremlin media, and of its impact, is irregular and often conducted privately or in-house by governments. Social media listening tools are only available to professional digital marketing companies; traditional media monitoring is conducted by credible organisations such as Detektor Media in Ukraine and Memo 98 in Slovakia, but the former only focuses on Ukraine while the latter works on discrete commissions.

The lack of publicly available consistent monitoring and impact assessment is a significant gap in the field, and one of the most urgent to redress. The sort of longitudinal focus groups necessary to gauge impact will require long-term investment.

GLOBSEC: STRATCOM PROGRAMME Through its Stratcom programme, Slovakia-based GLOBSEC runs a series of high profile research projects such as its annual GLOBSEC Trends report, which maps the effects of disinformation on public attitudes through a series of opinion polls in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia, three states vulnerable to Russian influence. This enabled them to compare public perceptions of the EU, NATO, and the role of the US in these countries over time. GLOBSEC serves as a model of what can be achieved when an organisation is given adequate funding. Their Stratcom programme is run by four people with external co-operators across the region.

PUBLIC CAMPAIGNS

Awareness-raising activities are of core importance as a tool for challenging the infiltration and spread of disinformation into the public consciousness. There are few organisations across Europe with the ability and resources to effectively design and deliver these, though there have been examples of successful campaigns which others could learn from.

There is huge potential here for upskilling the ability of organisations to conceptualise, deliver, monitor and evaluate campaigns that reach vulnerable audiences with information that challenges Kremlin narratives and undermines disinformation.

GLOBSEC: STRATCOM PROGRAMME GLOBSEC launched an inventive and engaging campaign using social media in order to bring attention to the risks posed by disinformation. They used two of the most popular Slovak bloggers to create a false online flame-war, pitting their fans against each other. There were subtle clues that the fight was false, and after several days it was revealed that it was a hoax to show people how easy it is to be fooled if information is not checked properly. The campaign achieved 1.2 million views in a country of 5 million; though it should be noted that there was some spill over into the Czech Republic. GLOBSEC assessed it as the most successful counter-disinformation campaign in the region.

NETWORK ANALYSIS

Any understanding of disinformation needs to take into account the networks through which narratives are spread and the digital techniques that are used to amplify them. Digital network analysis is at the cutting edge of evaluating disinformation, pioneered at academic institutions, digital marketing companies and select think tanks such as the Atlantic Council Digital Forensics Lab. It is now starting to be pursued by some media outlets such as El Pais. Private companies such as Graphika and Alto Data have experience mapping Kremlin and extremist networks for a variety of government and private clients. This mapping is key to both understanding the emerging field and for designing interventions.

“ In exposing Russian propaganda, you are fighting a ghost. If you approach counter disinformation without exposing the networks, you will fail.” Bulgaria Analytica

Exposing networks of sources that spread disinformation, rather than trying to counter specific stories and pieces of content, may be one of the most effective and sustainable ways of countering disinformation. A preponderance of evidence shows that when people are confronted with information which challenges the beliefs or values they already hold they are most likely to reject the information and further entrench their position. However, sensitively highlighting sources which people have previously trusted and showing that they are attempting to malignly influence the conversation can activate a sense of being manipulated and act as an affront to an individual’s deeper emotional and psychological need to see themselves as rational and informed.

In addition, nodes in disinformation networks tend to be active in multiple disinformation campaigns. For example, the Kremlin repurposed bot/troll accounts and exploited the same far left and far right communities for both the anti-White Helmets and pro-Brexit campaigns in the UK. Exposing this finite network of disinformation nodes can have a long term counterdisinformation impact.

However, the digital tools necessary for such research are expensive and available to few groups. There is an urgent need to proliferate tools among different organisations, to help with training on how to use them optimally and then pool research to understand Kremlin and pro-Kremlin networks. There is ample talent in many of these regions to develop this. Central Europe has excellent digital marketing companies and computer scientists, as have Ukraine and Belarus. Delfi has built a prototype for an Artificial Intelligence tool that tracks articles published by over 100 websites known to spread Russian disinformation, leading the way for research in that area.

DELFI: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE Delfi has built a prototype for a web-based AI tool that currently tracks articles across over 100 websites that are known to publish disinformation in Russian and Lithuanian. The tool can classify articles published by these websites by popularity, keywords, social media shares, author, or countries mentioned. The tool is monitored by about 300 volunteers who flag stories they believe are inaccurate or false, and then publish articles debunking them on the website. A full version of the tool is expected to be launched in late summer 2018. They hope to include other European languages and to add additional features, including the ability to subscribe to articles, an automated ‘fake score,” and a social media page and feed crawler.

INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM

Narrative-driven investigative journalism is increasingly proving an extremely powerful way to expose the Kremlin’s disinformation. Spectacular scoops have been obtained by Western, and more importantly Russian, journalists: years before media in the US was paying attention to the Internet Research Agency, courageous Russian journalists had already unmasked it. In the Czech Republic, journalists have investigated the ownership structures behind opaque pro- Kremlin disinformation websites. The Baltics have excellent investigative journalistic outfits who have exposed Kremlin strategies in the region.

Investigative journalism is however expensive, dangerous and sporadic. For greater impact, investigative journalism into disinformation needs to become more transnational and work in tandem with anti-corruption and counter-extremist organisations to uncover the financial backers of disinformation, and their intersection with far-right movements. Investigative journalism in this field also needs to be popularised so it can reach a broader audience, for example through narrative television and other accessible formats.

When smaller organisations have been equipped and upskilled to use their contextual and linguistic expertise to research and expose the narratives used by the Kremlin in their specific territories, this has proven an effective way of revealing both Kremlin tactics and the specific falsehoods that are being spread to local, vulnerable audiences.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 13

BELLINGCAT: MH17 Bellingcat, an online investigation website, was at the forefront of exposing what happened to the Malaysian airliner MH17. The website published photos that it alleged tracked the movement of a Russian missile linked to the downing of the aircraft. Its findings were examined by a Dutch-led team of investigators, who said that they had a ‘considerable interest’ in Bellingcat’s research output. Bellingcat has since published a comprehensive report that outlines the circumstances surrounding the incident and has gone further than official investigators in naming suspects.

MEDIA LITERACY

Media literacy is a critical component of countering disinformation and increasing resilience among the general population over the long term. Several innovative projects are updating media literacy training for the digital era, including IREX’s highly regarded ‘Learn to Discern’ program in Ukraine.

IREX: LEARN TO DISCERN IREX, a global development and education organisation, designed and implemented a program called ‘Learn to Discern’ in Ukraine. It is intended to address the problems associated with citizens not being able to detect disinformation. It encouraged people to support independent, truthful and ethical journalism, while teaching them how to tell whether something was true or false, or manipulative. An impact study showed that participants were 28% more likely to demonstrate sophisticated knowledge of the news media industry, 25% more likely to self-report checking multiple news sources, and 13% more likely to correctly identify and analyse a fake news story.

These efforts should be implemented within vulnerable populations, including the older generation, and could involve a multi-platform approach including online quizzes, games and TV shows, similar to the work of StopFake in Ukraine. Media literacy efforts represent a unique opportunity to involve sections of the population in active participation in fact-checking. This involves individuals learning through doing, and thinking critically about the media through their own active experiences rather than merely being told about potential distortions and the suspect provenance of the information they are consuming.

A range of tactics have proven effective in countering disinformation. These are utilised by organisations from media outlets to think tanks and grassroots implementers. A response must contain within its armoury a full range of tactics to be implemented at different times and in multiple contexts in response to an emerging and rapidly shifting threat.

CIVIL SOCIETY: THE THIRD LAYER IN THE FIGHT AGAINST DISINFORMATION

Countering disinformation must involve governments, the private sector, and civil society organisations. Each of these plays a unique role and must be working in parallel, achieving a joined-up approach.

Government responses to Kremlin influence operations in Europe and frontline states have on the whole been disjointed and responsive rather than pre-emptive. While some Western governments have started to signal concern around the issue, many remain unwilling to confront the Kremlin directly or have their own interests in amplifying a similar disinformation agenda. There is justified scepticism of the extent to which governments should get involved in any issues which touch on freedom of speech. Moreover, governments are limited by having to frame this issue purely in terms of ‘foreign’ campaigns against a ‘domestic’ information space, when the reality of today’s mediascape is that these distinctions are increasingly blurred.

The role of the private sector is to drive innovation through investing in research and tools that can be used by a wide range of organisations, including media outlets and civil society as a whole.

The upskilling of civil society organisations across Europe represents a unique opportunity for the FCO to adopt a joined-up approach, ensuring information sharing between the private sector, civil society and Government while enabling civil society organisations to counter disinformation in a way that matches the challenge in their local contexts.

UPSKILLING TO UPSCALE: UNLEASHING THE CAPACITY OF CIVIL SOCIETY TO COUNTER DISINFORMATION

Due to the scale and gravity of the threat across Europe, there are an increasing number of civil society organisations with a high commitment to understanding and countering Kremlin-backed disinformation, often doing so in the face of strong opposition and with little remuneration or support for their work. These include media outlets, think tanks, and grassroots projects that promote media literacy or community cohesion elements.

Civil society organisations are uniquely well-placed in this field, as they have the commitment, mission and potentially the credibility to not only counter disinformation but also build longterm resilience to it through positive messaging, lobbying to improve regulation, and building awareness and critical thinking among the public. However, the majority of these organisations are operating completely independently of one another in a disparate fashion without sharing best practice. Their outputs have varying degrees of quality and effectiveness and are typically not informed by the latest data and research. Furthermore, they have limited operational capacity to do this work at the pace and scale required.

An opportunity exists to upskill civil society organisations around Europe, enhancing their existing activities and unleashing their potential to effectively counter disinformation. If supported to deliver their activities in a professional manner, while gaining access to a variety of support functions, best practice and high-quality training, these organisations have the potential to be the next generation of activists in the fight against Kremlin disinformation.

OUR RESEARCH SUGGESTS THAT AN EFFECTIVE RESPONSE

TO DISINFORMATION MUST BE:

• Neutral to tactics; able to adopt a variety of tactics in response to emerging threats.

• Organic; able to emerge spontaneously and adoptive of linguistic and cultural nuances.

• Data-driven; incorporating a strong feedback loop and aware of the latest narratives and how they are being spread.

• Rapid; able to mobilise at a fast pace in line with the fast-moving disinformation networks utilised by the Kremlin.

• Locally embedded but transnationally networked; utilising the local media context and existing media outlets to disseminate content alongside the ability to see and respond to the transnational reach of Kremlin campaigns.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 16

STRATEGIC APPROACH

OBJECTIVES

The EXPOSE Network will involve identifying civil society organisations operating across Europe countering disinformation using a variety of tactics; upskilling these organisations in research and communications, and through the provision of operational support, grants and training; and coordinating their activities to ensure effectiveness and to measure impact through research and evaluation.

THIS WILL:

• Increase the quality and quantity of counter-disinformation content.

• Increase the sustainability and professionalism of organisations countering disinformation.

• Create an ecosystem of credible voices which can continue to grow and counter the disinformation ecosystem exploited by the Kremlin.

• Build awareness among key audiences, including policy makers, journalists, the general public, and influencers/amplifiers of Kremlin strategy, tactics and networks.

• Help establish best practice on countering disinformation.

THIS WILL CONTRIBUTE TO:

• Undermining the credibility of the Kremlin, their narratives and online networks.

• Building resilience to disinformation in vulnerable audiences across Europe.

• Reducing the number of unwitting multipliers of disinformation.

AUDIENCES

A holistic approach to countering disinformation will target a variety of audiences.

THESE INCLUDE:

• The wider public; through the dissemination of campaigns and exposing the networks and sources of disinformation. This would also take into account media literacy activities, increasing resilience among the general population.

• Governments; national and local governments as well as multilateral institutions through engagement, public affairs and advocacy.

• Policy makers; through coordinated research outputs network members will provide policy makers with a cohesive national and regional picture of disinformation and its impact, and typology of the narratives that are spread.

• Journalists and mainstream media outlets; through embedded investigative journalism projects and the mapping of networks and sources, network members will provide facts to journalists and mainstream media outlets that prevent falsehoods reaching the mainstream media.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 17

KEY BARRIERS TO COUNTERING DISINFORMATION EFFECTIVELY

Through online surveys and face-to-face interviews with 43 organisations in 14 countries a number of critical barriers to countering disinformation effectively have been revealed. From the challenges of operating under governments that are pro-Kremlin to the challenges in raising funds to deliver long-term work, as well as a lack of access to digital tools and learning opportunities, four trends can be identified across the region as a whole. The operating model proposed will address the following key barriers:

• Lack of expertise, guidance and tools to deliver high-quality open source research.

• Lack of ability and support to conceptualise and deliver public facing campaigns and communications products that challenge public perceptions about disinformation.

• Lack of access to grant funding, relationships with donors, and the ability to write funding proposals, severely limiting their sustainability, as well as qualified staff.

• Absence of security frameworks and legal training to run streamlined and low-risk operations.

These are covered in more detail in ANNEX A: Needs Assessment Findings.

RESEARCH

While good-quality research is an integral part of countering Russian disinformation, the capability of the organisations to do this effectively varies greatly. Fact-checking, monitoring social media, open source research, and mapping propagandist networks were identified as crucial tactics.

The capacity to conduct long-term research projects and in-depth investigations was the strongest area identified within the potential partners. However, the lack of awareness or adherence to the International Fact-Checking Code of Principles and the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) Code of Conduct was a potential limitation.

Organizations in countries with governments that are resistant to free and open journalism were the weakest in this regard. However, organizations in countries that are on the frontline of Russian disinformation campaigns and have governments focused on combatting the threat, such as Poland and the Baltic states, were identified as the strongest with regards to ethical journalism standards. However, even here, organizations do not formally stick to principles. Rather, they use what they describe as common sense and multiple source corroboration of evidence. A similar trend was identified in Belarus and Moldova. Organizations in Southern Europe were aware of the Poynter fact-checking principles and NUJ Code of Conduct; however, like other organisations, they did not officially adhere to them.

Fact-checking was identified as particularly strong capability within organisations in the Baltics. However, the fact-checking capability of potential partners in other regions is limited. It was not that organizations could not do this effectively, but rather that they questioned its efficacy. StopFake was a notable exception.

The inability of organisations to monitor social media was a far more significant gap identified. None of the organisations interviewed were aware of online listening tools. Organisations in the Balkans, Central Europe and Eastern Europe were the weakest in this regard. The same pattern was noted with regards to data science capabilities.

The ability to map and monitor propagandist networks, while strong in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, is limited in the rest of the network. Organizations in Georgia, for example, expressed a desire to enter this area but noted that they did not have the resources.

BULGARIA ANALYTICA: DATA SCIENCE As the use of algorithms and systems designed to extract knowledge and insight from data becomes an increasingly important part of the counter-disinformation toolkit, many organisations are keen to exploit this and to develop data science and AI capabilities. Bulgaria Analytica has expressed frustration that they do not have data science capabilities on their team, despite Bulgaria being extremely resource-rich in terms of people with data science skills (an estimated 40,000 people in Bulgaria are writing software for US companies). Additional funding to employ individuals with data science skills and to develop their in-house capabilities would ensure that this skill set could be used to tackle the disinformation threat.

COMMUNICATIONS

The research output generated by the organisations is limited in its impact if it is not read and understood by the public. Therefore, public communication is an integral part of countering disinformation. There were clear discrepancies in the ability and willingness of organisations to communicate their findings externally.

Organisations in ‘single-threat’ environments, where pro-Kremlin disinformation comes from Russian-affiliated sources, were found to be far more capable in this regard than organisations in ‘dual-threat’ countries, where local media echoes Kremlin narratives. Organisations in countries with governments that are supportive of the counter-disinformation effort operate in a far more conducive environment. Some, including Stop Fake and Detektor Media, receive government support. However, even they are limited in their ability to reach vulnerable audiences, such as Russian-speaking minorities in non-Russian speaking countries.

Out of eleven Central European organizations interviewed, only one, Globsec, is successfully reaching sizeable audiences, and none is reaching the most vulnerable communities, namely avid consumers of Kremlin disinformation.

Many organisations only carry out counter-disinformation activities online. This means that older members of vulnerable communities do not come across their counter-disinformation work. In the whole Baltic region only one organisation, the National Centre for Defense and Security Awareness, carries out offline activities.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 19

Organisations in ‘dual-threat’ environments face significant obstacles, as their governments are resistant to the work they are producing. For example, Euroradio is forced to broadcast to Belarus from Poland. Meanwhile, the biggest pro-Russian propaganda outlet in Bosnia is Radio Televizija Republike Srpske, a state media outlet. Organisations in this area therefore face a significant challenge from television broadcasters.

The reach of analysis done by think tanks and academic institutions is limited by a number of factors. Firstly, it is deep and comprehensive, meaning that reading it is time-intensive and it does not lend itself to being shared on social media. Moreover, some organisations are very resistant to broadcasting their work on Russian disinformation, as they believe that it will bring them unwanted attention.

MALDITO BULO: INSTAGRAM While Maldito Bulo has had success in promoting their work to the 30-50 age bracket, they have struggled to attract readers that do not use Twitter or Facebook. In order to increase their younger readership, they have begun to use Instagram to engage this audience. However, they do not have the resources to provide their staff with formal training. Instead, younger staff members who use Instagram try to explain the platform to older members who do not. They only have 1,661 followers on Instagram, compared to 140,000 on Twitter. It is evident that with additional training on digital communications and brand building they could dramatically increase their millennial readership.

SUSTAINABILITY

Most organisations interviewed mentioned the difficulty of generating enough funding to carry out their activities as effectively as possible.

Very few organisations in the Baltics have any experience of writing funding proposals and most had no awareness of funding opportunities available in their region or further afield.

Some organisations, such as Fundacja Reperterów in Poland, have begun to explore the possibility of using digital communications to raise awareness of their fundraising activities. However, their digital capabilities are also limited. This example serves to illustrate how capacity building in one area could have positive results across the full range of required capabilities. Several of the organisations interviewed reported frustrations that their team were not able to dedicate themselves full-time to the effort to counter disinformation due to the need to seek additional employment.

OPERATIONAL SUPPORT

Many organisations will require significant legal advice and ongoing support, as currently they do not operate within a procedural framework. More than 80% of organisations surveyed do not have any anti-bribery and anti-corruption policy or code of conduct in place. Meanwhile, only 5% of organisations interviewed provide basic training in legal compliance. The Bribery Act 2010 could have far reaching implications for network members. While only a small percentage of organisations had faced allegations of bribery or corruption, there was no uniformity in how organisations thought such allegations should be dealt with.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 20

Moreover, over 80% of the organisations do not have a written discrimination policy. This presents risks as it limits the ability of the organisation to ensure compliance to their duties under the Equality Act 2010. New GDPR legislation could create additional problems for the organisations. Less than half of them had trained their teams in how to comply with the legislation.

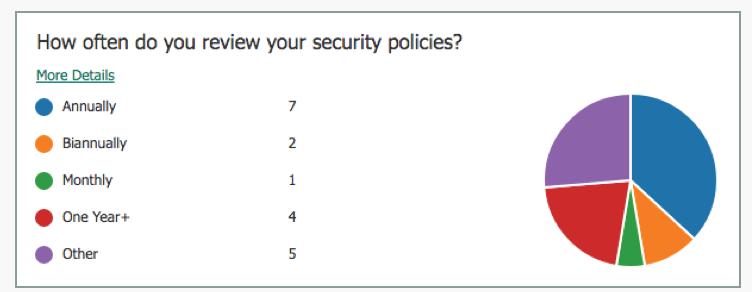

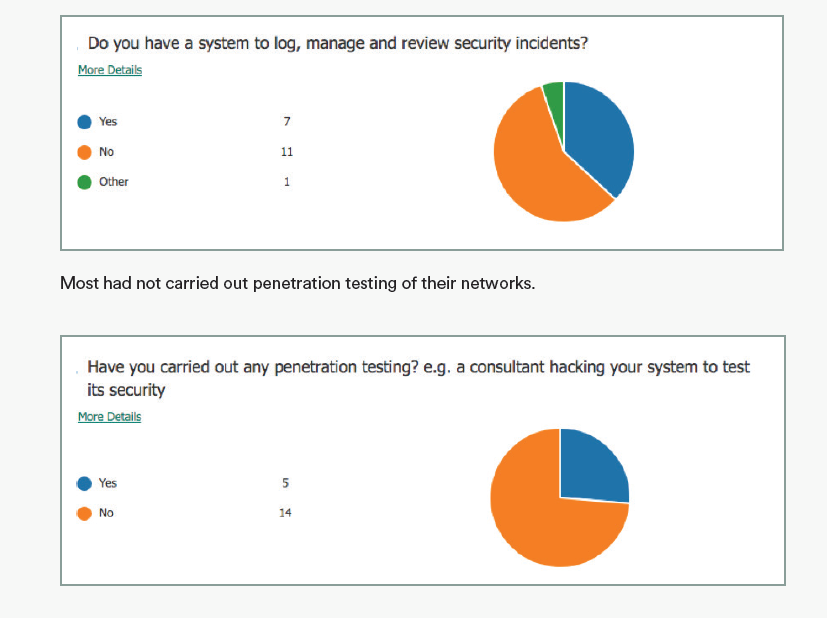

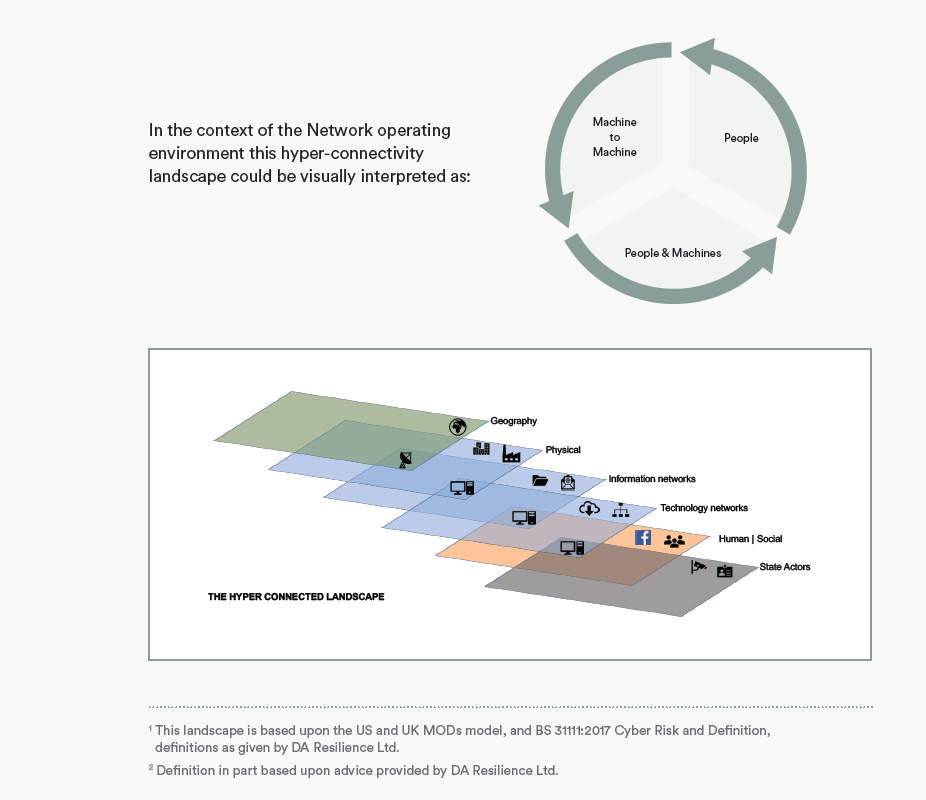

In terms of cyber security, many organizations did not have any information security policies in place or relied on very basic information security training. Of the organisations that did have an information security policy in place, only one reviewed it monthly, and most only reviewed it annually.

We found that the biggest weakness with regards to operational support found across the entire network was the subjectivity of risk management. Most organisations did not have a formal system for identifying and preventing risks, and instead responded in an ad hoc manner. Moreover, we found that some partners had not identified a framework for responding to a security breach, or a process for informing relevant stakeholders that one had occurred.

A significant area for improvement is the lack of consistency with regards to what devices are permitted in the workplace. Many partners allowed staff to bring their own devices into work, despite the risks posed from devices that are not centrally managed and are therefore easier to compromise. As a device being compromised could allow a threat-actor to access sensitive data relating to the network, strategies will have to be put in place to minimise this risk. There is also a threat from the compromise of data due to human error or intention. Many organisations have no systems in place to prevent their staff from removing data, and some do not vet their staff.

While working as part of a partnership, it is important that all organisations apply the same process to communicate a breach to client and affected parties. It is advisable that a central policy is determined to manage these scenarios.

LATVIAN ELVES: WEAKNESSES IN CYBER SECURITY AND VULNERABLE TO ATTACK The Latvian Elves desperately need capacity building with regards to cyber security. The Elves are predominantly volunteers that belong to a 180-person strong Facebook group, rather than formal staff. The volunteers engage in debates and discussions online in order to raise questions about disinformation. This makes them highly visible to malign actors. Although they create blacklists and grey-lists of accounts suspected of being pro-Kremlin trolls, they have still experienced cyber-attacks. Some members of the Facebook group have even been doxed. (doxing: to search for and publish private or identifying information about an individual on

the internet, typically with malicious intent)

Several key weaknesses exist across research, communications, sustainability and operational functioning. The model below sets out to bring together organisations in such a way as to effectively address these gaps and weaknesses.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 21

OPERATING MODEL

The EXPOSE Network will bring together organisations from across Europe already committed to countering disinformation, increase their technical skills and provide holistic operational support to enable them to professionalise and upscale their activities. The Network Facilitator will coordinate these activities and gain valuable information about their impact, while also increasing the ability of organisations to better understand their own impact and to tailor their activities accordingly.

The Network Facilitator will be based in a low-risk European country, hosting a team of technical specialists able to travel regionally to support organisations depending on their strategy and the response the current geopolitical climate requires.

The network will be coordinated through a Central Hub run by the Network Facilitator. In addition to the organisations initially selected, membership will be open to new members on a rolling basis if they meet the initial criteria.

Membership of the network will provide training, tools and funding for research, and will facilitate transnational cooperation and public engagement. In turn, members will have to sign up to a mandatory code of ethics, standards and research methodologies, which will have to be maintained across any research carried out within the network.

The Network Facilitator will coordinate the activities of network members across borders, bringing together disparate implementations in order to streamline, ensure peer-to-peer learning, develop relationships between partners and measure effectiveness. It will also connect the Network’s activities to parallel organisations looking at corruption and extremism issues, such as the OCCRP and OCCI.

The ongoing monitoring and evaluation will provide a comprehensive picture of activities happening across Europe and their impact on a micro and macro level, and will give the FCO the ability to coordinate activity in response to specific events or narratives being spread by Kremlin-backed media.

Figure 1: A diagram of the Network illustrating the relationships between the Network Facilitator, Network Members and Audiences

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 22

NETWORK MEMBERS

We recommend the Network encompasses a broad spectrum of organisations. The selection process has been designed to identify a longer list of potential network members spanning a variety of tactics to counter misinformation, and a broad subset of cross-cutting issues. The process has also taken into account the priority countries and regions set out by the FCO, representing a joined-up European-wide approach to combating misinformation from organisations that hold the most potential to do so.

The majority of potential network members included in this longlist are cognizant of efforts to counter disinformation and are already engaging in this space, but additional organisations have been included who have high potential due to their skill set or the issues they engage with. The organisations identified are, therefore, either already highly competent in some of the necessary tactics in the counter-disinformation sphere or display potential, given the right guidance and advice, to become highly effective actors in this arena.

Disinformation campaigns are often complex, and undertaken through a series of networks that feature both state actors and non-state actors with overlapping interests, some grounded in truth but disingenuously framed, others entirely false. Therefore, core to our approach is engaging with narratives and issues that intersect with Russian misinformation. We have selected organisations that are engaging with issues that might not be perceived at first glance to be Russian misinformation, for example far-right narratives, anti-migration narratives and pro-separatist narratives. Organisations are also included who are combatting corruption, representing untapped potential in a core area that ties to disinformation.

If the equipped network is employing a diverse set of tactics and engaging with a variety of cross-cutting issues and narratives, the Network Facilitator will be able to monitor how campaigns develop locally and across borders, and how they are effectively countered. Ultimately the data created by such a network showing the effectiveness of certain interventions will also become a lynchpin in designing and executing projects to measurably reduce and counter the impact of disinformation.

Some of these organisations are leaders in their fields, operating at scale and with globally recognised outputs, for example Bellingcat and DFR Lab, while others are smaller and still defining their offering, such as Bulgaria Analytica and Krik. The activities offered by the Network that each will want to participate in will therefore be different, and the potential for peer-to-peer learning is huge. Network partners such as DFR Lab could deliver training packages to smaller organisations as part of the scope offered by the Network Facilitator.

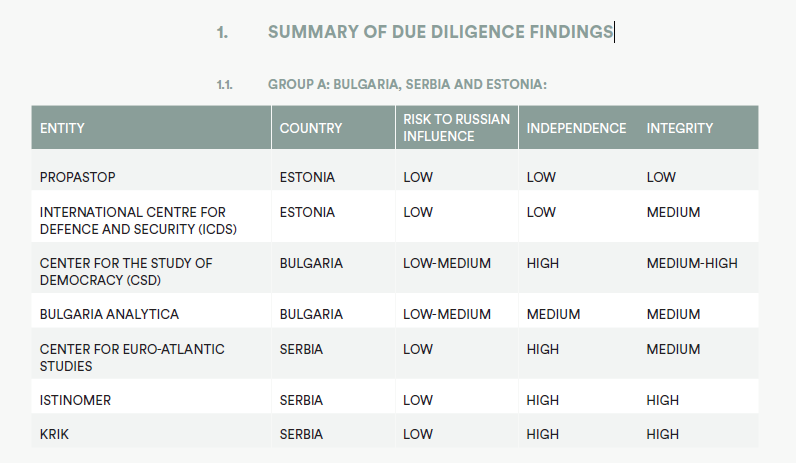

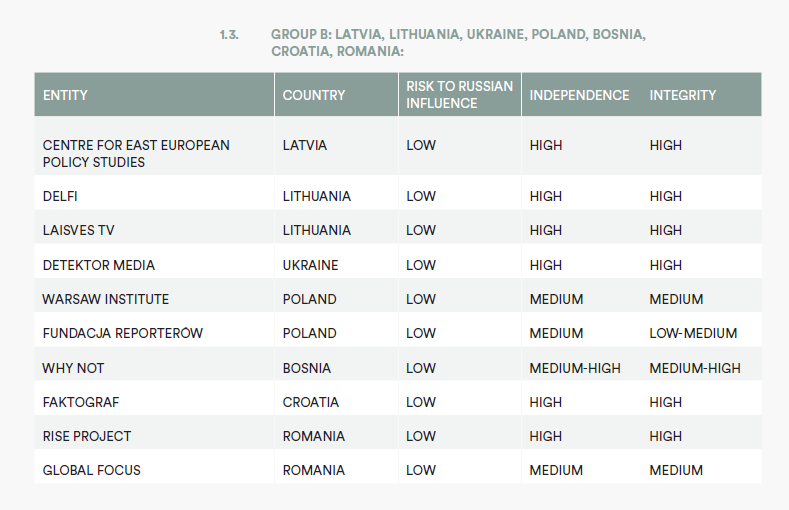

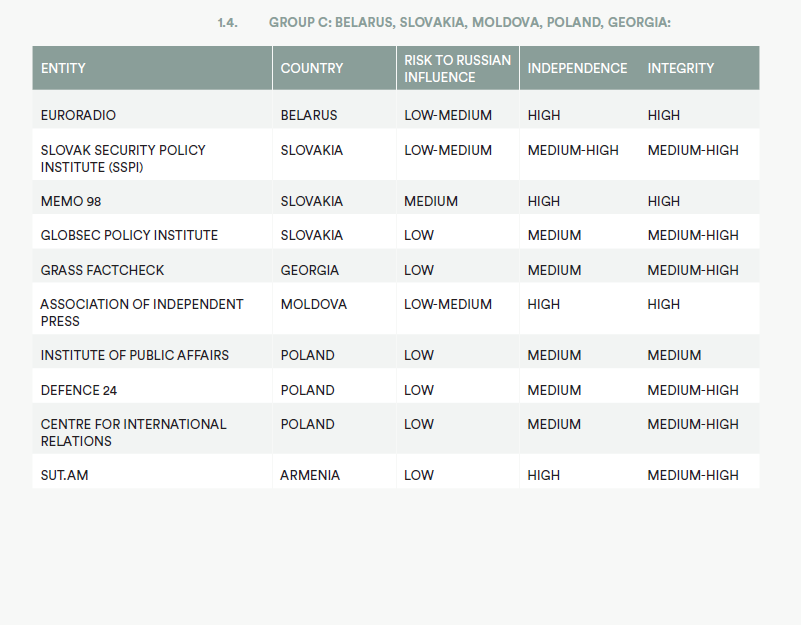

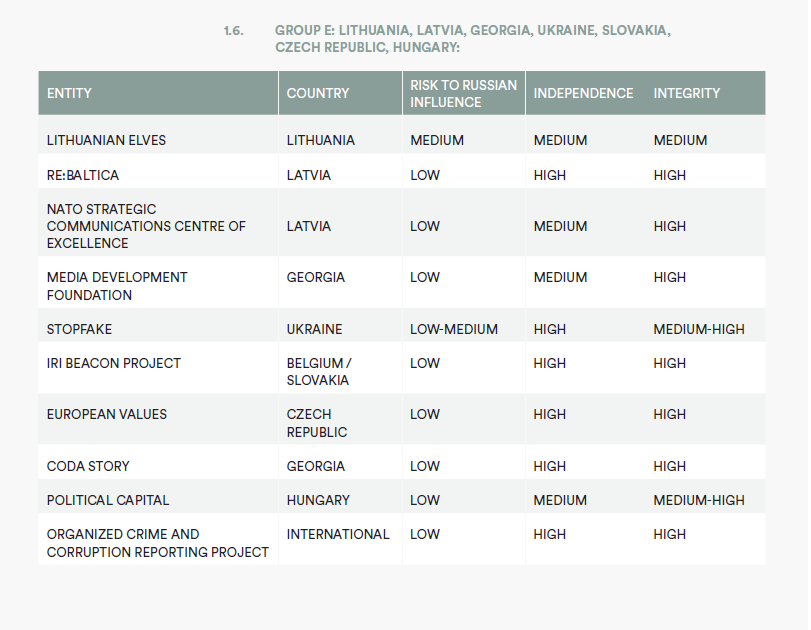

Each partner has been assessed for inclusion involving a comprehensive due diligence process (ANNEX B: Risk Management Framework), their track record in identifying and tackling disinformation, its reputation and mission statement and objectives.

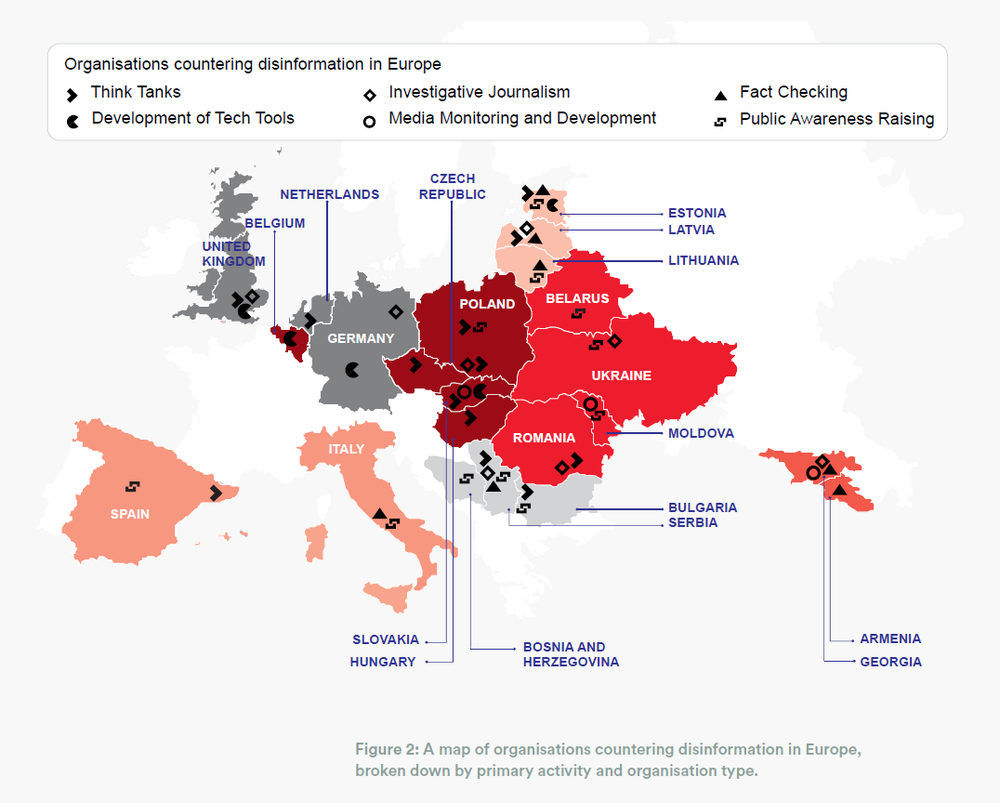

Figure 2: A map of organisations countering disinformation in Europe, broken down by primary activity and organisation type.

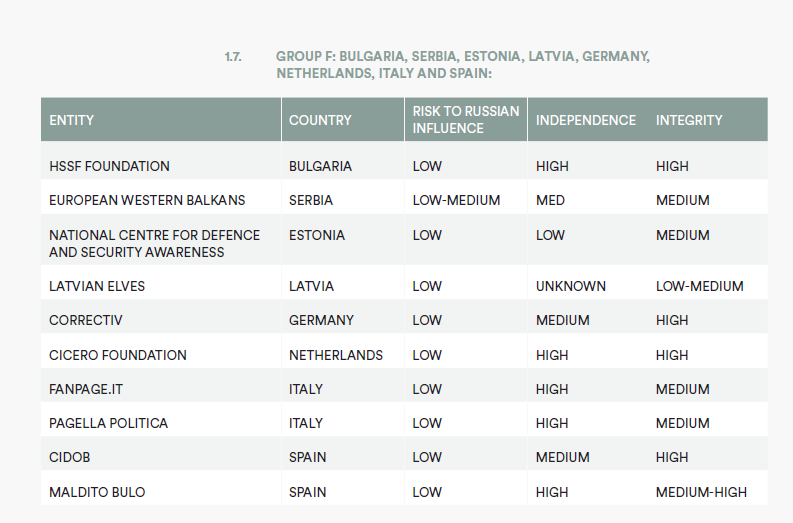

BALKANS:

• Why Not Bosnia

• Bulgaria Analytica Bulgaria

• Center for the Study of Democracy Bulgaria

• HSSF Foundation Bulgaria

• Center for Euro-Atlantic Studies Serbia

• European Western Balkans Serbia

• Istinomer Serbia

• Krik Serbia

BALTICS:

• International Centre for Defence and Security Estonia

• National Centre for Defence and Security Awareness Estonia

• Centre for East European Policy Studies Latvia

• Latvian Elves Latvia

• NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence Latvia

• Re:Baltica Latvia

• Lithuanian Elves Lithuania

• Delfi Lithuania

• Laisves TV Lithuania

CENTRAL EUROPE:

• European Values Czech Republic

• The Prague Security Studies Institute Czech Republic

• Political Capital Hungary

• Center for European Policy Analysis Poland

• Center for International Relations Poland

• Centre for Propaganda and Disinformation Analysis Poland

• Kosciuszko Institute Poland

• Defence 24 Poland

• Fundacja Reporterów Poland

• Institute of Public Affairs Poland

• Warsaw Institute Poland

• GLOBSEC Policy Institute Slovakia

• Institute for Public Affairs Slovakia

• IRI Beacon Project Slovakia and Belgium

• Memo 98 Slovakia

• Slovak Security Policy Institute Slovakia

CAUCASUS:

• Sut.am Armenia

• Coda Story Georgia

• GRASS FactCheck Georgia

• Media Development Foundation Georgia

EASTERN EUROPE:

• Euroradio Belarus

• Association of Independent Press Moldova

• Newsmaker Moldova

• ZDG Moldova

• Global Focus Romania

• RISE Project Romania

• Detektor Media Ukraine

• StopFake Ukraine

SOUTHERN EUROPE:

• Fanpage.it Italy

• Pagella Politica Italy

• CIDOB Spain

• Maldito Bulo Spain

WESTERN EUROPE:

• Correctiv Germany

• Cicero Foundation Netherlands

• Bellingcat U.K.

• Factmata U.K.

• Institute for Strategic Dialogue U.K.

INTERNATIONAL:

• DFRLab

• Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

We recommend that these organisations above be invited to participate in the EXPOSE Network, ensuring a broad geographical reach as well as the potential to engage with many cross-cutting issues and to adopt a variety of tactics.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 25

NETWORK ACTIVITIES

The Network Facilitator will deliver five core activity strands. These will run in parallel throughout the three-year implementation period. Resourcing will include a grant funding mechanism, and will ensure that organisations have access to legal, security and other operations support to enable them to deliver their work within a safe and well-resourced environment. Training will include a variety of learning packages, from online courses to embedded learning with dedicated specialists and regional events focused on topics including cyber security and enhancing communications outputs. The Quality Assurance (QA) strand will ensure that wherever possible outputs from Network members are created within rigorous journalism, fact-checking and legal frameworks and will drive to increase quality in both research and communications. Coordination of activities and network members will foster synergies between research interests, promote regional cooperation, and will facilitate networking, as well as drawing together activities and promoting specific approaches if necessary. Research and evaluation of impact will involve both a study of disinformation as it emerges online and the evaluation of the activities of network members to better understand their impact on the target audiences.

Figure 3: The Network Facilitator’s five core activity strands.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 26

RESOURCING

A) GRANTS MECHANISM

In addition to support and training, the Network will run a small grants mechanism programme for network members. This will ensure that smaller organisations without the capacity or ability to apply for large grants can receive funding in a quick turnaround cycle for smaller discreet activities that can otherwise be hard to fund.

Project Grants

Given the current spread of activity among potential network members and the gaps that exist, we recommend that grants should be awarded based on the following objectives:

• Improve coordinated research outputs into disinformation and its impact

• Increase public resilience to disinformation among vulnerable audiences

Seed Funding

We also recommend that grants be given to cover core funding over longer periods of time for smaller organisations, providing a guaranteed income that enables them to upscale and focus on delivery. There are a number of potential project partners whose work would be substantially enhanced if they had seed funding that freed up the founding members to deliver work rather than run day-to-day operations and fundraise. To receive these awards organisations would have to provide a three-year business projection of income and activities.

Applicants

These grants would work best when granted only to members of the EXPOSE Network. Members of the network will have already undergone vetting, entered into memorandums of understanding with the Network Facilitator, and complied with basic security guidelines while committing to developing more rigorous procedures.

Organisational Structure and Governance

Applications will be assessed by a Steering Committee, comprised of between eight and ten individuals representing larger organisations with a strong track record countering disinformation such as DFR Lab and the Atlantic Council, experts in delivering behaviour change campaigns and experts in research. These individuals should be representative of at least four different countries across Europe. This Steering Committee will be managed by the Network Facilitator.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 27

B) LEGAL ADVICE AND SUPPORT

The network facilitator will offer a comprehensive legal support function, able to provide organisations with guidance on copyright, data protection and GDPR, and corruption and bribery. Alongside training, detailed later in the report, this would include ring-fenced days of legal support for a legal consultant to advise each organisation on their most pressing challenges, and pulling together a specific list of recommendations tailored to each organisation.

We also recommend ongoing support in the way of a dedicated email address for members to send their legal enquiries to, which can be prioritised by the Network Facilitator so that members can be signposted to the right support.

This will ensure that members are equipped to maintain high standards of integrity and compliance with international statutes, reducing their risk and increasing their long-term sustainability, and protecting their reputation and thus the reputation of efforts to counter disinformation Europe-wide. This will in turn protect the reputation of the FCO and other donor communities.

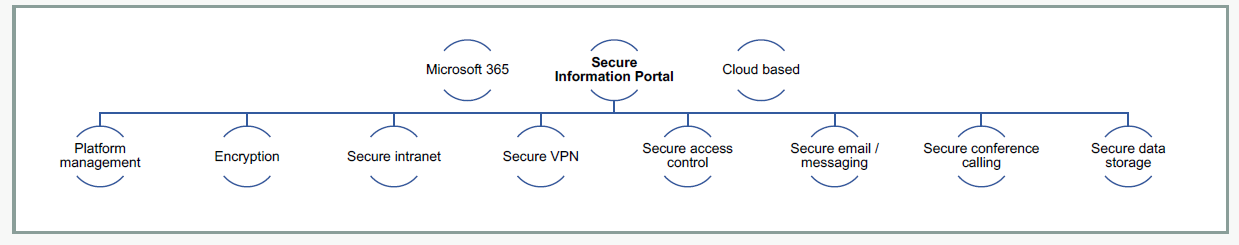

C) SECURITY SUPPORT

The network will offer ongoing security support including hosting a secure communications and information sharing network (See ANNEX C: Information Sharing Protocol). Members will be required to sign up to a basic code of conduct regarding cyber security, with milestones established throughout the three years of the programme duration that will take them to a higher level. These minimum guidelines will include:

• Device protocol; limit the access of data to personal devices. Ensure that all devices that can access network information are either centrally-managed by network members, or that they have to be approved and whitelisted by senior members of staff at member organisations.

• A cyber threat management and reporting function; members will be responsible for reporting cyber threats to the Network Facilitator and to using software to tracks threats as they emerge.

• Staff vetting; provide a basic framework that network members must use when initially screening applicants for jobs in order to vet whether candidates could expose the network to any potential threats.

• Physical security; in specific countries standards for physical security would be laid out to include personal security and the security of buildings.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 28

In addition, the Network Facilitator would provide:

• Continued risk assessment and analysis: this would inform a periodic security briefing but can also be used to brief partners of imminent issues or areas of weakness

• Periodic security briefing by geography

• Physical infrastructure security survey on a request basis or where partners are high risk

• Independent verification of source networks or individuals on request

TECHNICAL TRAINING

Training must be a core component of the Network. Access to high quality, free training is limited and in some cases impossible for organisations operating in high risk environments. Furthermore, the niche activities that network members are engaged in require specialist training that is hard to access.

We envision five barriers to learning:

• Size of organisations; the majority of the organisations surveyed are small, with teams of less than ten full-time staff, and without dedicated staff building up a strong skill set in one area. They must be encouraged and supported to upscale in order to ensure learning is spread evenly and that skill sets have the opportunity to deepen.

• Time pressure; organisations working to counter disinformation are operating in a fast-moving and pressured environment with a need to respond rapidly. Coupled with a lack of resources, this can result in a de-prioritisation of learning.

• Lack of resources; training must be accompanied with access to the right tools and software in order to ensure that learning can be capitalised on and translate to measurable outputs.

• Complex political and social environments; network members are operating in different political and social environments. Those in ‘dual threat’ environments may attempt to upskill while also facing governmental pressure and combatting extreme propagandist content. These present challenges to learning due to the restrictions placed on these organisations as well as the time pressures they face, and require a flexible and tailored learning approach.

• Skill disparity; while some organisations in the Network are operating at scale and have developed deep skill sets in specific areas such as fact-checking or investigative journalism, others require introductory-level training in a number of areas.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 29

In order to address these barriers, the training offered by the Network Facilitator must be:

• Flexible; taking into account that many organisations face significant time pressure and need to spread out training alongside other activities and commitments . • Tailored to context; aware that each organisation operates in a different environment and that approaches to research, legal and security concerns will vary.

• Easily accessible; tailored to the learning mechanisms that organisations regularly use and made engaging for learners of different levels.

• Peer-to-peer based where possible; utilising the skills of the more established members of the network in order to spread knowledge regionally and foster closer cooperation.

• Integrated within a resourcing structure; tied to the provision of specific tools, e.g. social listening training to be accompanied by the licensing of social monitoring tools for use by network members.

Training topics can be selected from the four learning areas previously identified: research, communications, sustainability and operational functioning.

D) RESEARCH

Training modules and programmes to enhance research skills should cover:

• Investigative journalism; developing the ability of Network members to use open source tools to identify specific disinformation narratives, particularly in response to events. There are a number of partners in the network who could deliver training in this stream.

• Journalism standards; developing awareness of the NUJ Code of Conduct, National Code of Conduct, and Poynter’s Fact-Checking Code of Principles along with giving practical advice on how to implement these.

• Social media monitoring; provide training and tools to track Kremlin disinformation and responses online, as well as gauging the impact of counter narratives.

• Open source research; not only training but building the capacity of organisations to conduct digital investigations using open source approaches that can support both their investigative journalism and fact-checking activities. These skills could include, for example, geolocation of images and films, identification of deep fakes, and time coding and sequencing to establish lines of causation.

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 30

Training modules and programmes to enhance communications skills should include:

• Behavioural science driven campaign development; train network members on how to target vulnerable audiences in their communications by identifying formats, messengers, and mediums that will resonate with their target audiences.

• Content creation; supporting network members to turn their outputs into engaging content, both digital and offline that is tailored to their audience’s needs. This could include, for example, commissioning social video, press engagement, or partnering with broadcast TV and radio

• Digital promotion and targeting; supporting Network members to identify their audiences online through segmentation and analysis, use social media promotion (paid and organic) to ensure content is reaching their intended target audience, and use analytics and comment coding to iteratively optimise their content and dissemination.

• Event planning workshops; provide network members with the capacity and knowledge to plan and run events that further their objectives, addressing the lack of counterdisinformation activities occurring offline.

• Brand building; provide training on how to build online and offline brand engagement that will increase their audience share as well as positioning them credibly to vulnerable audiences.

• Design; provide Network members with the ability to use a full range of design software to create compelling content to share on social media channels, and to condense complex reports into easily shareable infographics.

F) SUSTAINABILITY

Training modules designed to increase the sustainability of network members should include:

• Grant proposal training; offer network members training on how to look for grant opportunities and how to write a successful application.

• Budget design; training on how to design budgets for a variety of potential donors

• Business planning; bespoke modules for different types of operation model, helping organisations to plan for future activities and to think about new types of income generation

© PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT. NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION 31

Alongside a significant resource component supporting organisations with legal and security compliance, a training component should include:

• EU media law; provide training sessions in order to ensure that network members comply with EU law when reporting. This should minimize their risk of being sued and limit the potential loss of credibility associated with having to retract stories

• EU employment law; provide training to all network members to ensure that they understand their duties under the Equality Act 2010 and that they have the ability to adhere to it

• Bribery and anti-corruption training; work with network members to establish an anti-corruption and anti-bribery policy that all members will comply with

• GDPR; train all staff at network member organisations on how to comply with data protection legislation

• Risk management; training on how to design a risk management framework

• Cyber security; training on protecting organisations online

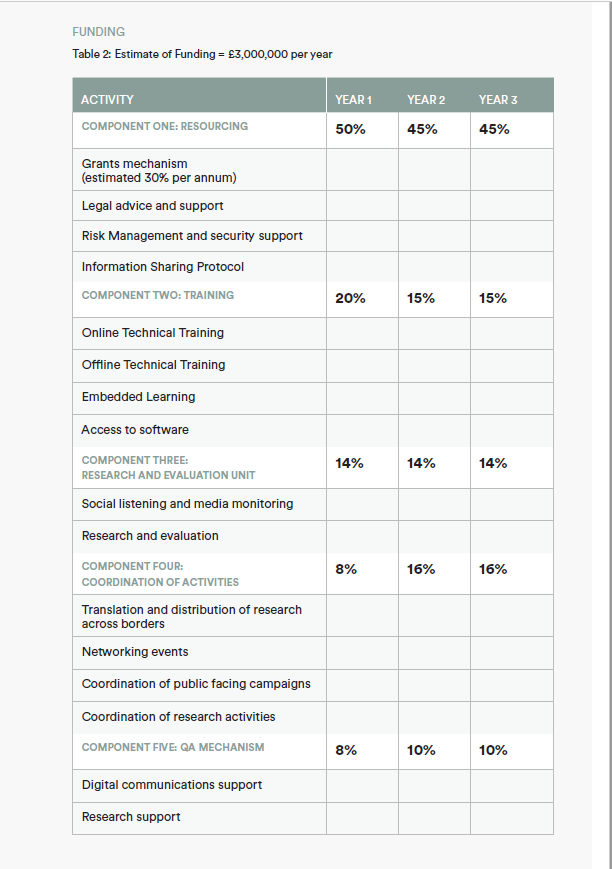

RESEARCH AND EVALUATION OF IMPACT