Difference between revisions of "Manus Island"

m (tidy) |

m (description) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

|map=Admiralty Islands Topography with labels.png | |map=Admiralty Islands Topography with labels.png | ||

|coordinates= | |coordinates= | ||

| − | |description= | + | |description=Pacific island with large US and Australian military/intelligence presence. |

}} | }} | ||

'''Manus Island''' is an island in northern [[Papua New Guinea]] (PNG) and is the largest of the [[Admiralty Islands]]. The former colonial power [[Australia]] kept a base on Manus until PNG's independence in 1974. Because the island has "a fine strategic location that dominates this part of the Pacific"<ref name=Aspi>https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/benefits-all-manus-being-base-us-australia-forces</ref>, Australia, and also the [[United States]], have showed continued interest in the island. | '''Manus Island''' is an island in northern [[Papua New Guinea]] (PNG) and is the largest of the [[Admiralty Islands]]. The former colonial power [[Australia]] kept a base on Manus until PNG's independence in 1974. Because the island has "a fine strategic location that dominates this part of the Pacific"<ref name=Aspi>https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/benefits-all-manus-being-base-us-australia-forces</ref>, Australia, and also the [[United States]], have showed continued interest in the island. | ||

Latest revision as of 23:52, 20 October 2022

(Island, Military base, US military base, Black site) | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Pacific island with large US and Australian military/intelligence presence. |

Manus Island is an island in northern Papua New Guinea (PNG) and is the largest of the Admiralty Islands. The former colonial power Australia kept a base on Manus until PNG's independence in 1974. Because the island has "a fine strategic location that dominates this part of the Pacific"[1], Australia, and also the United States, have showed continued interest in the island.

Contents

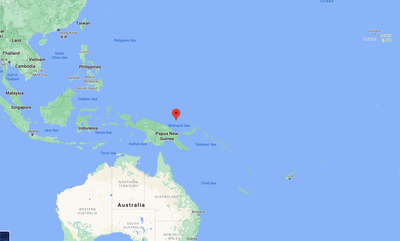

Location

It is the fifth-largest island in Papua New Guinea, with an area of around 2,100 km2 (810 sq mi), and a population of around 50,000. Manus Island is covered in rugged jungles. The highest point on Manus Island is Mt. Dremsel, 718 metres (2,356 ft) above sea level at the centre of the south coast.

Lorengau, the capital of Manus Province, is located on the island. Momote Airport, the terminal for Manus Province, is located on nearby Los Negros Island. A bridge connects Los Negros Island to Manus Island and the provincial capital of Lorengau. The Austronesian Manus languages are spoken on the island.

The Australian-run Manus Regional Processing Centre was situated on Los Negros Island from 2001 to 2017, to house asylum seekers arriving by boat found within Australia's defined territorial borders.

Base Upgrade

In June 2021, the Australian ABC announced the Australian Defence Force would spend $175 million on a major upgrade for "Papua New Guinea's naval base on Manus Island". In support of this action, the state channel interviewed locals calling for "Australia to create long-term employment opportunities on Manus". The base upgrade, announced in 2018, includes an extension of the current wharf facility, improvements to the island's road and electricity network, and new accommodation and training facilities.[2]

The base will be owned and run by the PNGDF but Australian troops "will also be able to use the facility for joint training exercises and mentoring programs".[2]

Manus could also be a forward operating base to support American naval units, as the US is interested in examining locations to support operations in the Pacific,[1], and the island "enables multiple lines of operations".[3]

Manus Regional Processing Centre

The Manus Regional Processing Centre was one of a number of offshore Australian immigration detention facilities. The Centre was located on the PNG Navy Base Lombrum (previously a Royal Australian Navy base) on Los Negros Island in Manus Province, Papua New Guinea.

It was originally established in 2001, along with Nauru Regional Processing Centre, as an "offshore processing centre" (OPC) as part of the Pacific Solution policy created by the Howard government. After falling into disuse in 2003, it was formally closed by the first Rudd government in 2008, but reopened by the Gillard government in 2012. As part of the PNG Solution by the second Rudd government, it was announced in July 2013 that those sent to PNG would never be resettled in Australia. After Tony Abbott a few months later, the government announced its Operation Sovereign Borders policy, aimed at stopping maritime arrivals of asylum seekers to Australia, commencing on 18 September 2013.

Many high-profile and ordinary Australians called for the Centre to be closed and the men brought to Australia or resettled elsewhere, over the seven years of its existence. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has cited the centre as an "indictment of a policy meant to avoid Australia's international obligations". It was formally closed on 31 October 2017; however hundreds of detainees ("transferees" according to the Australian government) refused to leave the centre and a stand-off ensued. On 23 November 2017, a few were resettled in the United States as part of a refugee swap deal.

Between August and November 2019, the last former detainees were moved to Port Moresby, with the government's regional processing contractors instructed to terminate services on 30 November 2019.

In January 2018 home affairs minister Peter Dutton refused an order from the Senate to release documents relating to the health, construction and security services for Manus. One of the contracts causing controversy was that signed with security firm Paladin Solutions, a group run by two Australians,[4] which was earning AU$72m for providing security for four months (about AU$585,000 a day). There was at the time a dispute with a local security firm, Kingfisher, who thought that they should have been given the contract.[5]

In February 2019, the Australian government extended its contract with Paladin, promising an extra $109 million, to provide maintenance and other services to the East Lorengau Transit Centre. This made the Paladin Group one of the biggest government contractors in Australia, at AU$423 million for its 22 months of work on Manus. Asylum seekers in the centre reported that maintenance was very poor, and a July 2018 report UNHCR noted below-standard facilities, leaking pipes and showers not working in East Lorengau, although there had been improvements in the other camps.[4] It was reported that the government had not run an open tender process for contracts worth AU$423 million to provide security for the asylum seekers,[6] and further that Paladin had left a number of bad debts and failed contracts across Asia and had moved ownership of its Australian entity from Hong Kong to Singapore. Peter Dutton sought to distance himself, saying that he had "no sight" of the tender process. The Australian Financial Review calculated that the daily cost per detainee of the service was more than double the rate for a suite in a 5-star hotel with views of Sydney Harbour.[7]

Australia's history of using the island for offshore processing goes back to the 1960s, when Manus Island was set up to take refugees from West Papua.[8] Known as "Salasia Camp", it consisted of a few corrugated iron houses on a bare concrete slab, not far from a beach near the main town Lorengau. Indonesia was preparing a military takeover of the former Dutch New Guinea colony in the 1960s, causing thousands of refugees, known as "West Irians" to flee into the then Australian colony of Papua New Guinea. Many were turned back by Australian patrol officers on the border but a few dozen received special visas and the first were sent to Manus in 1968 by the Australian government, to a camp was built by Australia in order to avoid a diplomatic confrontation with Indonesia. According to historian Klaus Neumann of Deakin University, "Australia had not objected to Indonesia's takeover of the Dutch colony, and Australia had recognised Indonesia was now in charge of former Western New Guinea, so for Australia to grant refugee status posed a diplomatic problem". So by sending them to the remotest place in PNG the Australian authorities thought they would avoid any trouble with Indonesia. The camp was not a detention centre, and many stayed on, stateless, until in 2017, these West Papuans were finally offered PNG citizenship.[9]

World War 2

During World War 2 Manus was first bombed by the Japanese on 25 January 1942, the radio mast being the main target.[10] On 8 April 1942 an Imperial Japanese invasion force entered Lorengau harbour and several hundred Japanese soldiers of the 8th Special Base Force went ashore onto the Australian-mandated island. The vastly outnumbered Australians withdrew into the jungle.[10] Manus Island became the site of an observation post manned by Australian naval spotters, who were very successful.[10][11]

Later in 1942, Japan established a military base on Manus Island. This was attacked by United States forces in the Admiralty Islands campaign of February – March 1944.[12] An Allied naval base was established at Seeadler Harbor on the island and it later supported the British Pacific Fleet. The ammunition ship USS Mount Hood exploded in Seeadler Harbor on 10 November 1944 with a heavy loss of life of US Navy personnel.

In 1950–51 the Australian government conducted the last trials against Japanese war criminals on the island.[13] One case heard was that of Takuma Nishimura, who faced an Australian military court. He had already been tried by a British military court in relation to the Sook Ching massacre in Singapore and sentenced to life imprisonment. While on a stopover in Hong Kong he was intercepted by Australian Military Police. Evidence was presented stating that Nishimura had ordered the shootings of wounded Australian and Indian soldiers at Parit Sulong and the disposal of bodies so that there was no trace of evidence. In this trial he was found guilty and was hanged on 11 June 1951.

American anthropologist Margaret Mead lived on Manus Island before and after the war, and gave detailed accounts in Growing up in New Guinea and New Lives for Old.

Rating

References

- ↑ a b https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/benefits-all-manus-being-base-us-australia-forces

- ↑ a b https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-15/major-naval-base-on-png-manus-island-lombrum-adf/100216040

- ↑ https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018/december/strategic-significance-manus-island-us-navy

- ↑ a b https://www.afr.com/news/policy/foreign-affairs/cashing-in-on-refugees-duo-make-20-million-a-month-at-manus-island-20190210-h1b2e5

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/jan/18/dutton-refuses-senate-order-to-release-details-of-refugee-services-contracts-on-manus

- ↑ https://www.afr.com/news/policy/foreign-affairs/home-affairs-ran-closed-tenders-for-paladins-lucrative-manus-security-contracts-20190212-h1b5ym

- ↑ https://www.afr.com/news/politics/national/peter-dutton-had-no-sight-of-manus-contractor-paladin-20190213-h1b7jk

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20190220093208/https://www.sbs.com.au/news/a-history-of-australia-s-offshore-detention-policy

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20190218092253/https://www.sbs.com.au/news/fifty-years-in-the-making-refugees-in-australia-s-first-manus-camp-offered-png-citizenship

- ↑ a b c https://warfare.gq/dutcheastindies/manus.html

- ↑ https://warfare.gq/dutcheastindies/medical.html

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.39003

- ↑ Piccigallo, Philip; The Japanese on Trial; Austin 1979; ISBN 0-292-78033-8, ch.: "Australia".