Difference between revisions of "Fingerprint"

(add image) |

m (description) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

|image=Fingerprinting.jpg | |image=Fingerprinting.jpg | ||

|constitutes=technology | |constitutes=technology | ||

| + | |description=Markers of human identity collected in huge government databases | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Human '''fingerprints''' are easily detectable, nearly unique, marks of identity which are difficult to alter. [[Authorities]] are building various databases of people's fingerprints. Some [[nation state]]s such as [[Japan]] have forbidden entry to people unless they give some of all of their fingerprints to the [[authorities]]. | + | Human '''fingerprints''' are easily detectable, nearly unique, marks of identity which are difficult to alter, making them suitable as long-term markers of human identity, although the technique has been somewhat overtaken by new identification techniques such as [[facial recognition]], [[voiceprints]], [[DNA]] samples and [[biometric data]]. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Authorities]] are building various databases of people's fingerprints. Some [[nation state]]s such as [[Japan]] have forbidden entry to people unless they give some of all of their fingerprints to the [[authorities]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==FBI and Fingerprinting== | ||

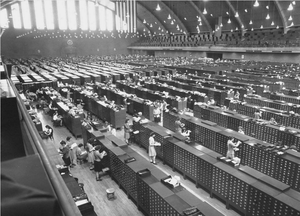

| + | [[image:FBI fingerprint collection 1944.png|thumb|The fingerprint files of FBI, 1944]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since 1924, the [[FBI]] has been the single U.S. repository for fingerprints. By [[1942]] the FBI was adding 400,000 file cards a month to its archives, and were receiving 110,000 requests for “name checks” per month. By 1944 the agency contained some 23 million card records, as well as 10 million fingerprint records.<ref>https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/fbi-fingerprint-files-facility-1944/</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For its first 75 years of existence, the processing of incoming fingerprint cards by the FBI was predominantly a manual, time consuming, labor intensive process. Fingerprint cards were mailed to the FBI for processing and a paper-based response was mailed back. It would take anywhere from weeks to months to process a fingerprint card.<ref>https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/news/testimony/fbi-fingerprint-program</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Computers were first installed to search these files in [[1980]]. Since 1999, the FBI has stored and accessed its fingerprint database via the digital IAFIS ([[Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System]]) It is a national [[automated fingerprint identification]] and criminal history system. IAFIS provides automated [[fingerprint]] search capabilities, latent searching capability, electronic image storage, and electronic exchange of fingerprints and responses. IAFIS houses the fingerprints and criminal histories of 70 million subjects in the criminal master file, 31 million civil prints and fingerprints from 73,000 known and suspected terrorists processed by the U.S. or by international law enforcement agencies.<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20120921125141/http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/fingerprints_biometrics/iafis/iafis/ </ref> US Visit currently holds a repository of the fingerprints of over 50 million non-US citizens, primarily in the form of two-finger records. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Validity == | ||

| + | Fingerprints collected at a crime scene, or on items of evidence from a crime, have been used in [[forensic science]] to identify suspects, victims and other persons who touched a surface. Fingerprint identification emerged as an important system within police agencies in the late 19th century, when it replaced anthropometric measurements as a more reliable method for identifying persons having a prior record, often under a false name, in a criminal record repository.<ref>http://onin.com/fp/ridgeology.pdf</ref> Fingerprinting has served all governments worldwide during the past 100 years or so to provide identification. Fingerprints are the fundamental tool in every police agency for the identification of people with a criminal history.<ref>http://onin.com/fp/ridgeology.pdf</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The validity of forensic fingerprint evidence has been challenged by academics, judges and the media. In the [[United States]] fingerprint examiners have not developed uniform standards for the identification of an individual based on matching fingerprints. In some countries where fingerprints are also used in criminal investigations, fingerprint examiners are required to match a number of ''identification points'' before a match is accepted. In England 16 identification points are required and in France 12, to match two fingerprints and identify an individual. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Point-counting methods have been challenged by some fingerprint examiners because they focus solely on the location of particular characteristics in fingerprints that are to be matched. Fingerprint examiners may also uphold the ''one dissimilarity doctrine'', which holds that if there is one dissimilarity between two fingerprints, the fingerprints are not from the same finger. Furthermore, academics have argued that the [[per-comparison error rate|error rate]] in matching fingerprints has not been adequately studied. And it has been argued that fingerprint evidence has no secure [[statistical]] foundation.<ref>Paul Roberts (2017). Expert Evidence and Scientific Proof in Criminal Trials. Routledge.</ref> Research has been conducted into whether experts can objectively focus on feature information in fingerprints without being misled by extraneous information, such as context.<ref>https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0379073805005876</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fingerprints can theoretically be forged and planted at crime scenes.<ref>https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/abstract.aspx?ID=202212</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2004 Madrid bombings=== | ||

| + | In 2004, [[Brandon Mayfield]], an attorney from [[Oregon]], USA, was arrested as a material witness by the [[FBI]] because his fingerprint matched a latent found at the scene of the [[Madrid train bombings]] which killed 191 people and injured hundreds more. Mayfield was held for 17 days before Spanish authorities conducted their own analysis and found the real culprit: an Algerian national, [[Ouhnane Daoud]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Consumer electronics login authentication == | ||

| + | Since 2000 electronic fingerprint readers have been introduced as [[consumer electronics]] security applications. [[Fingerprint sensor]]s could be used for [[login]] [[authentication]] and the identification of computer users. However, some less sophisticated sensors have been discovered to be vulnerable to quite simple methods of deception, such as fake fingerprints cast in [[gel]]s. In 2006, fingerprint sensors gained popularity in the [[laptop]] market. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Two of the first smartphone manufacturers to integrate fingerprint recognition into their phones were Motorola with the [[Motorola Atrix 4G|Atrix 4G]] in 2011 and Apple with the [[iPhone 5S]] on September 10, 2013. One month after, HTC launched the [[HTC One Max|One Max]], which also included fingerprint recognition. In April 2014, Samsung released the [[Samsung Galaxy S5|Galaxy S5]], which integrated a fingerprint sensor on the home button.<ref> http://webcusp.com/list-of-all-fingerprint-scanner-enabled-smartphones/ </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following the release of the [[iPhone 5S]] model, a group of German hackers announced on September 21, 2013, that they had bypassed Apple's new Touch ID fingerprint sensor by photographing a fingerprint from a glass surface and using that captured image as verification. The spokesman for the group stated: "We hope that this finally puts to rest the illusions people have about fingerprint biometrics. It is plain stupid to use something that you can't change and that you leave everywhere every day as a security token."<ref>http://news.cnet.com/8301-13579_3-57604067-37/hackers-claim-to-have-defeated-apples-touch-id-print-sensor/</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 2017 [[Hewlett-Packard|Hewlett Packard]], [[Asus]], [[Huawei]], [[Lenovo]] and [[MacBook Pro#Fourth generation (Touch Bar and USB-C)|Apple]] were using fingerprint readers in their laptops.<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20170710214806/http://pcworld.com/article/3187448/laptop-computers/hp-spectre-x360-2017-review-the-best-just-keeps-getting-better.html|archive-date=July 10, 2017}</ref><ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20170815190727/https://www.digitaltrends.com/laptop-reviews/asus-transformer-t304-review/</ref><ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20170816154510/https://www.laptopmag.com/reviews/laptops/lenovo-thinkpad-t570</ref> [[Synaptics]] says the SecurePad sensor is now available for [[Original equipment manufacturer|OEMs]] to start building into their laptops.<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20170816191620/https://www.engadget.com/2014/12/10/synaptics-securepad/</ref> In the newest smartphones, the fingerprint reader is being integrated into the whole touchscreen display instead of as a separate sensor. | ||

==UK== | ==UK== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

In February 2018, some [[UK police]] were given scanners to allow them to take people's fingerprints on the street.<ref>http://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/02/12/west_yorkshire_police_fingerprint_scanner_trial/</ref> | In February 2018, some [[UK police]] were given scanners to allow them to take people's fingerprints on the street.<ref>http://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/02/12/west_yorkshire_police_fingerprint_scanner_trial/</ref> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 45: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 08:09, 19 March 2021

(technology) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Markers of human identity collected in huge government databases |

Human fingerprints are easily detectable, nearly unique, marks of identity which are difficult to alter, making them suitable as long-term markers of human identity, although the technique has been somewhat overtaken by new identification techniques such as facial recognition, voiceprints, DNA samples and biometric data.

Authorities are building various databases of people's fingerprints. Some nation states such as Japan have forbidden entry to people unless they give some of all of their fingerprints to the authorities.

Contents

FBI and Fingerprinting

Since 1924, the FBI has been the single U.S. repository for fingerprints. By 1942 the FBI was adding 400,000 file cards a month to its archives, and were receiving 110,000 requests for “name checks” per month. By 1944 the agency contained some 23 million card records, as well as 10 million fingerprint records.[1]

For its first 75 years of existence, the processing of incoming fingerprint cards by the FBI was predominantly a manual, time consuming, labor intensive process. Fingerprint cards were mailed to the FBI for processing and a paper-based response was mailed back. It would take anywhere from weeks to months to process a fingerprint card.[2]

Computers were first installed to search these files in 1980. Since 1999, the FBI has stored and accessed its fingerprint database via the digital IAFIS (Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System) It is a national automated fingerprint identification and criminal history system. IAFIS provides automated fingerprint search capabilities, latent searching capability, electronic image storage, and electronic exchange of fingerprints and responses. IAFIS houses the fingerprints and criminal histories of 70 million subjects in the criminal master file, 31 million civil prints and fingerprints from 73,000 known and suspected terrorists processed by the U.S. or by international law enforcement agencies.[3] US Visit currently holds a repository of the fingerprints of over 50 million non-US citizens, primarily in the form of two-finger records.

Validity

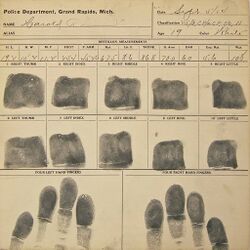

Fingerprints collected at a crime scene, or on items of evidence from a crime, have been used in forensic science to identify suspects, victims and other persons who touched a surface. Fingerprint identification emerged as an important system within police agencies in the late 19th century, when it replaced anthropometric measurements as a more reliable method for identifying persons having a prior record, often under a false name, in a criminal record repository.[4] Fingerprinting has served all governments worldwide during the past 100 years or so to provide identification. Fingerprints are the fundamental tool in every police agency for the identification of people with a criminal history.[5]

The validity of forensic fingerprint evidence has been challenged by academics, judges and the media. In the United States fingerprint examiners have not developed uniform standards for the identification of an individual based on matching fingerprints. In some countries where fingerprints are also used in criminal investigations, fingerprint examiners are required to match a number of identification points before a match is accepted. In England 16 identification points are required and in France 12, to match two fingerprints and identify an individual.

Point-counting methods have been challenged by some fingerprint examiners because they focus solely on the location of particular characteristics in fingerprints that are to be matched. Fingerprint examiners may also uphold the one dissimilarity doctrine, which holds that if there is one dissimilarity between two fingerprints, the fingerprints are not from the same finger. Furthermore, academics have argued that the error rate in matching fingerprints has not been adequately studied. And it has been argued that fingerprint evidence has no secure statistical foundation.[6] Research has been conducted into whether experts can objectively focus on feature information in fingerprints without being misled by extraneous information, such as context.[7]

Fingerprints can theoretically be forged and planted at crime scenes.[8]

2004 Madrid bombings

In 2004, Brandon Mayfield, an attorney from Oregon, USA, was arrested as a material witness by the FBI because his fingerprint matched a latent found at the scene of the Madrid train bombings which killed 191 people and injured hundreds more. Mayfield was held for 17 days before Spanish authorities conducted their own analysis and found the real culprit: an Algerian national, Ouhnane Daoud.

Consumer electronics login authentication

Since 2000 electronic fingerprint readers have been introduced as consumer electronics security applications. Fingerprint sensors could be used for login authentication and the identification of computer users. However, some less sophisticated sensors have been discovered to be vulnerable to quite simple methods of deception, such as fake fingerprints cast in gels. In 2006, fingerprint sensors gained popularity in the laptop market.

Two of the first smartphone manufacturers to integrate fingerprint recognition into their phones were Motorola with the Atrix 4G in 2011 and Apple with the iPhone 5S on September 10, 2013. One month after, HTC launched the One Max, which also included fingerprint recognition. In April 2014, Samsung released the Galaxy S5, which integrated a fingerprint sensor on the home button.[9]

Following the release of the iPhone 5S model, a group of German hackers announced on September 21, 2013, that they had bypassed Apple's new Touch ID fingerprint sensor by photographing a fingerprint from a glass surface and using that captured image as verification. The spokesman for the group stated: "We hope that this finally puts to rest the illusions people have about fingerprint biometrics. It is plain stupid to use something that you can't change and that you leave everywhere every day as a security token."[10]

By 2017 Hewlett Packard, Asus, Huawei, Lenovo and Apple were using fingerprint readers in their laptops.[11][12][13] Synaptics says the SecurePad sensor is now available for OEMs to start building into their laptops.[14] In the newest smartphones, the fingerprint reader is being integrated into the whole touchscreen display instead of as a separate sensor.

UK

In February 2018, some UK police were given scanners to allow them to take people's fingerprints on the street.[15]

References

- ↑ https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/fbi-fingerprint-files-facility-1944/

- ↑ https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/news/testimony/fbi-fingerprint-program

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20120921125141/http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/fingerprints_biometrics/iafis/iafis/

- ↑ http://onin.com/fp/ridgeology.pdf

- ↑ http://onin.com/fp/ridgeology.pdf

- ↑ Paul Roberts (2017). Expert Evidence and Scientific Proof in Criminal Trials. Routledge.

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0379073805005876

- ↑ https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/abstract.aspx?ID=202212

- ↑ http://webcusp.com/list-of-all-fingerprint-scanner-enabled-smartphones/

- ↑ http://news.cnet.com/8301-13579_3-57604067-37/hackers-claim-to-have-defeated-apples-touch-id-print-sensor/

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20170710214806/http://pcworld.com/article/3187448/laptop-computers/hp-spectre-x360-2017-review-the-best-just-keeps-getting-better.html%7Carchive-date=July 10, 2017}

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20170815190727/https://www.digitaltrends.com/laptop-reviews/asus-transformer-t304-review/

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20170816154510/https://www.laptopmag.com/reviews/laptops/lenovo-thinkpad-t570

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20170816191620/https://www.engadget.com/2014/12/10/synaptics-securepad/

- ↑ http://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/02/12/west_yorkshire_police_fingerprint_scanner_trial/